A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Doha

الدوحة | |

|---|---|

Counter-Clockwise from top: the skyline of Doha at night; modern buildings in West Bay district; Amiri Diwan, which serves as the office of the Emir of Qatar; Souq Waqif; National Museum of Qatar; Musheireb downtown Doha; and Katara Cultural Village | |

| Coordinates: 25°17′12″N 51°32′0″E / 25.28667°N 51.53333°E | |

| Country | Qatar |

| Municipality | Doha |

| Established | 1825 |

| Area | |

| • City proper | 132 km2 (51 sq mi) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City proper | 1,186,023 |

| • Density | 9,000/km2 (23,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| Website | visitqatar.com/doha |

Doha (Arabic: الدوحة, romanized: ad-Dawḥa [adˈduħa] or ad-Dūḥa) is the capital city and main financial hub of Qatar. Located on the Persian Gulf coast in the east of the country, north of Al Wakrah and south of Al Khor, it is home to most of the country's population.[1] It is also Qatar's fastest growing city, with over 80% of the nation's population living in Doha or its surrounding suburbs, known collectively as the Doha Metropolitan Area.[2]

Doha was founded in the 1820s as an offshoot of Al Bidda. It was officially declared as the country's capital in 1971 when Qatar gained independence from being a British protectorate.[3] As the commercial capital of Qatar and one of the emergent financial centers in the Middle East, Doha is considered a beta-level global city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network. Doha accommodates Education City, an area devoted to research and education, and Hamad Medical City, an administrative area of medical care. It also includes Doha Sports City, or Aspire Zone, an international sports destination that includes Khalifa International Stadium, Hamad Aquatic Centre; and the Aspire Dome.

The city was host to the first ministerial-level meeting of the Doha Development Round of World Trade Organization negotiations. It was also selected as host city of several sporting events, including the 2006 Asian Games, the 2011 Pan Arab Games, the 2019 World Beach Games, the FINA World Aquatics Championships, the FIVB Volleyball Club World Championship, the WTA Finals and most of the games at the 2011 AFC Asian Cup. In December 2011, the World Petroleum Council held the 20th World Petroleum Conference in Doha.[4] Additionally, the city hosted the 2012 UNFCCC Climate Negotiations and the 2022 FIFA World Cup.[5] The city will host the 2027 FIBA Basketball World Cup.

The city also hosted the 140th Inter-Parliamentary Union Assembly in April 2019 and hosted the 18th yearly session of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2012. Doha has been named as the second safest city in the world in the Numbeo Crime Index by City 2021.[6] The index tracks safety in 431 cities.[7]

Etymology

According to the Ministry of Municipality and Environment of Doha, the name "Doha" originated from the Arabic term dohat, meaning "roundness"—a reference to the rounded bays surrounding the area's coastline.[8]

History

Establishment of Al Bidda

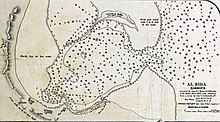

The city of Doha was formed seceding from another local settlement known as Al Bidda. The earliest documented mention of Al Bidda was made in 1681 by the Carmelite Convent, in an account that chronicles several settlements in Qatar. In the record, the ruler and a fort in the confines of Al Bidda are alluded to.[9][10] Carsten Niebuhr, a German explorer who visited the Arabian Peninsula, created one of the first maps to depict the settlement in 1765 in which he labelled it as 'Guttur'.[9][11]

David Seaton, a British political resident in Muscat, wrote the first English record of Al Bidda in 1801. He refers to the town as 'Bedih' and describes the geography and defensive structures in the area.[12] He stated that the town had recently been settled by the Sudan tribe (singular Al-Suwaidi), whom he considered to be pirates. Seaton attempted to bombard the town with his warship, but returned to Muscat upon finding that the waters were too shallow to position his warship within striking distance.[13][14]

In 1820, British surveyor R. H. Colebrook, who visited Al Bidda, remarked on the recent depopulation of the town. He wrote:[13][15]

Guttur – Or Ul Budee , once a considerable town, is protected by two square Ghurries near the seashore; but containing no freshwater they are incapable of defense except against sudden incursions of Bedouins, another Ghurry is situated two miles inland and has fresh water with it. This could contain two hundred men. There are remaining at Ul Budee about 250 men, but the original inhabitants, who may be expected to return from Bahrein, will augment them to 900 or 1,000 men, and if the Doasir tribe, who frequent the place as divers, again settle in it, from 600 to 800 men.

The same year, an agreement known as the General Maritime Treaty was signed between the East India Company and the sheikhs of several Persian Gulf settlements (some of which were later known as the Trucial Coast). It acknowledged British authority in the Persian Gulf and sought to end piracy and the slave trade. Bahrain became a party to the treaty, and it was assumed that Qatar, perceived as a dependency of Bahrain by the British, was also a party to it.[16] Qatar, however, was not asked to fly the prescribed Trucial flag.[17] As punishment for alleged piracy committed by the inhabitants of Al Bidda and breach of the treaty, an East India Company vessel bombarded the town in 1821. They razed the town, forcing between 300 and 400 natives to flee and temporarily take shelter on the islands between Qatar and the Trucial Coast.[18]

Formation of Doha

Doha was founded in the vicinity of Al Bidda sometime during the 1820s.[19] In January 1823, political[clarification needed] resident John MacLeod visited Al Bidda to meet with the ruler and initial founder of Doha, Buhur bin Jubrun, who was also the chief of the Al-Buainain tribe.[19][20] MacLeod noted that Al Bidda was the only substantial trading port in the peninsula during this time. Following the founding of Doha, written records often conflated Al Bidda and Doha due to the extremely close proximity of the two settlements.[19] Later that year, Lt. Guy and Lt. Brucks mapped and wrote a description of the two settlements. Despite being mapped as two separate entities, they were referred to under the collective name of Al Bidda in the written description.[21][22]

In 1828, Mohammed bin Khamis, a prominent member of the Al-Buainain tribe and successor of Buhur bin Jubrun as chief of Al Bidda, was embroiled in controversy. He had murdered a native of Bahrain, prompting the Al Khalifa sheikh to imprison him. In response, the Al-Buainain tribe revolted, provoking the Al Khalifa to destroy the tribe's fort and evict them to Fuwayrit and Ar Ru'ays. This incident allowed the Al Khalifa additional jurisdiction over the town.[23][24] With essentially no effective ruler, Al Bidda and Doha became a sanctuary for pirates and outlaws.[25]

In November 1839, an outlaw from Abu Dhabi named Ghuleta took refuge in Al Bidda, evoking a harsh response from the British. A. H. Nott, a British naval commander, demanded that Salemin bin Nasir Al-Suwaidi, chief of the Sudan tribe (Suwaidi) in Al Bidda, take Ghuleta into custody and warned him of consequences in the case of non-compliance. Al-Suwaidi obliged the British request in February 1840 and also arrested the pirate Jasim bin Jabir and his associates. Despite the compliance, the British demanded a fine of 300 German krones in compensation for the damages incurred by pirates off the coast of Al Bidda; namely for the piracies committed by bin Jabir. In February 1841, British naval squadrons arrived in Al Bidda and ordered Al-Suwaidi to meet the British demand, threatening consequences if he declined. Al-Suwaidi ultimately declined on the basis that he was uninvolved in bin Jabir's actions. On 26 February, the British fired on Al Bidda, striking a fort and several houses. Al-Suwaidi then paid the fine in full following threats of further action by the British.[25][26]

Isa bin Tarif, a powerful tribal chief from the Al Bin Ali tribe, moved to Doha in May 1843. He subsequently evicted the ruling Sudan tribe and installed the Al-Maadeed and Al-Kuwari tribes in positions of power.[27] Bin Tarif had been loyal to the Al Khalifa, however, shortly after the swearing-in of a new ruler in Bahrain, bin Tarif grew increasingly suspicious of the ruling Al Khalifa and switched his allegiance to the deposed ruler of Bahrain, Abdullah bin Khalifa, whom he had previously assisted in deposing of. Bin Tarif died in the Battle of Fuwayrit against the ruling family of Bahrain in 1847.[27]

Arrival of the House of Al Thani

The Al Thani family migrated to Doha from Fuwayrit shortly after Bin Tarif's death in 1847 under the leadership of Mohammed bin Thani.[28][29] In the proceeding years, the Al Thani family assumed control of the town. At various times, they swapped allegiances between the two prevailing powers in the area: the Al Khalifa of Bahrain and the Bin Saudis.[28]

In 1867, many ships and troops were sent from Bahrain to assault the towns Al Wakrah and Doha over a series of disputes. Abu Dhabi joined on Bahrain's behalf due to the perception that Al Wakrah served as a refuge for fugitives from Oman. Later that year, the combined forces sacked the two Qatari towns with around 2,700 men in what would come to be known as the Qatari–Bahraini War.[30][31] A British record later stated that "the towns of Doha and Wakrah were, at the end of 1867 temporarily blotted out of existence, the houses being dismantled and the inhabitants deported".[32]

The joint Bahraini-Abu Dhabi incursion and subsequent Qatari counterattack prompted the British political agent, Colonel Lewis Pelly, to impose a settlement in 1868. Pelly's mission to Bahrain and Qatar and the peace treaty that resulted were milestones in Qatar's history. It implicitly recognized Qatar as a distinct entity independent from Bahrain and explicitly acknowledged the position of Mohammed bin Thani as an important representative of the peninsula's tribes.[33]

In December 1871, the Ottomans established a presence in the country with 100 of their troops occupying the Musallam fort in Doha. This was accepted by Mohammad bin Thani's son, Jassim Al Thani, who wished to protect Doha from Saudi incursions.[34] The Ottoman commander, Major Ömer Bey, compiled a report on Al Bidda in January 1872, stating that it was an "administrative centre" with around 1,000 houses and 4,000 inhabitants.[35]

Disagreement over tribute and interference in internal affairs arose, eventually leading to the Battle of Al Wajbah in March 1893. Al Bidda Fort served as the final point of retreat for Ottoman troops. While they were garrisoned in the fort, their corvette fired indiscriminately at the townspeople, killing many civilians.[36] The Ottomans eventually surrendered after Jassim Al Thani's troops cut off the town's water supply.[37] An Ottoman report compiled the same year reported that Al Bidda and Doha had a combined population of 6,000 inhabitants, jointly referring to both towns by the name of 'Katar'. Doha was classified as the eastern section of Katar.[35][38] The Ottomans held a passive role in Qatar's politics from the 1890s onward until fully relinquishing control during the beginning of the first World War.[16]

20th century

Pearling had come to play a pivotal commercial role in Doha by the 20th century. The population increased to around 12,000 inhabitants in the first half of the 20th century due to the flourishing pearl trade.[39] A British political resident noted that should the supply of pearls drop, Qatar would 'practically cease to exist'.[40] In 1907, the city accommodated 350 pearling boats with a combined crew size of 6,300 men. By this time, the average prices of pearls had more than doubled since 1877.[41] The pearl market collapsed that year, forcing Jassim Al Thani to sell the country's pearl harvest at half its value. The aftermath of the collapse resulted in the establishment of the country's first custom house in Doha.[40]

Lorimer report (1908)

British administrator and historian J. G. Lorimer authored an extensive handbook for British agents in the Persian Gulf entitled Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf in 1908. In it, he gives a comprehensive account of Doha at the time:

Generally so styled at the present day, but Bedouins sometimes call it Dohat-al-Qatar, and it seems to have been formerly better known as Bida' (Anglice "Bidder"): it is the chief town of Qatar and is situated on the eastern side of that peninsula, about 63 miles south of its extremity at Ras Rakan and 45 miles north of Khor-al Odaid Harbour. Dohah stands on the south side of a deep bay at the south-western corner of a natural harbor which is about 3 miles in extent and is protected on the north-east and south-east sides by natural reefs. The entrance, less than a mile wide, is from the east between the points of the reefs; it is shallow and somewhat difficult, and vessels of more than 15 feet draught cannot pass. The soundings within the basin vary from 3 to 5 fathoms and are regular: the bottom is white mud or clay.

Townsite and quarters, — The south-eastern point of the bay are quite low but the land on the western side is stony desert 40 or 50 feet above the level of the sea. The town is built up the slope of some rising ground between these two extremes and consists of 9 Fanqs or quarters, which are given below in their order from the east to the west and north: the total frontage of the place upon the sea is nearly 2 miles.[42]

Lorimer goes on to list and describe the districts of Doha, which at the time included the still-existing districts of Al Mirqab, As Salatah, Al Bidda and Rumeilah.[43] Remarking on Doha's appearance, he states:

The general appearance of Dohah is unattractive; the lanes are narrow and irregular the houses dingy and small. There are no date palms or other trees, and the only garden is a small one near the fort, kept up by the Turkish garrison.[44]

As for Doha's population, Lorimer asserts that "the inhabitants of Dohah are estimated to amount, inclusive of the Turkish military garrison of 350 men, to about 12,000 souls". He qualified this statement with a tabulated overview of the various tribes and ethnic groups living in the town.[44]

British protectorate (1916–1971)

In April 1913, the Ottomans agreed to a British request that they withdraw all their troops from Qatar. Ottoman presence in the peninsula ceased, when in August 1915, the Ottoman fort in Al Bidda was evacuated shortly after the start of World War I.[45] One year later, Qatar agreed to be a British protectorate with Doha as its official capital.[46][47]

Buildings at the time were simple dwellings of one or two rooms, built from mud, stone, and coral. Oil concessions in the 1920s and 1930s, and subsequent oil drilling in 1939, heralded the beginning of slow economic and social progress in the country. However, revenues were somewhat diminished due to the devaluation of pearl trade in the Persian Gulf brought on by the introduction of the cultured pearl and the Great Depression.[48] The collapse of the pearl trade caused a significant population drop throughout the entire country.[39] It was not until the 1950s and 1960s that the country saw significant monetary returns from oil drilling.[16]

Qatar was not long in exploiting the new-found wealth from oil concessions, and slum areas were quickly razed to be replaced by more modern buildings. In 1950, British adviser to the Emir, Phillip L. Plant, initiated several municipal projects. Starting with remodeling the old complex of the Old Amiri Palace, Plant then initiated the construction of a seaside road about a half-mile in length which opened up and made accessible the half dozen jetties along Doha's most built-up section.[49] The first formal boys' school was established in Doha in 1952, followed three years later by the establishment of a girls' school.[50] Historically, Doha had been a commercial port of local significance. However, the shallow water of the bay prevented bigger ships from entering the port until the 1970s, when its deep-water port was completed. Further changes followed with extensive land reclamation, which led to the development of the crescent-shaped bay.[51] From the 1950s to 1970s, the population of Doha grew from around 14,000 inhabitants to over 83,000, with foreign immigrants constituting about two-thirds of the overall population.[52]

Post-independence

Qatar officially declared its independence in 1971, with Doha as its capital city.[3] In 1973, the University of Qatar was opened by emiri decree,[53] and in 1975 the Qatar National Museum opened in what was originally the ruler's palace.[54] During the 1970s, all old neighborhoods in Doha were razed and the inhabitants moved to new suburban developments, such as Al Rayyan, Madinat Khalifa and Al Gharafa. The Doha Metropolitan Area's population grew from 89,000 in the 1970s to over 434,000 in 1997. Additionally, land policies resulted in the total land area increasing to over 7,100 hectares (about 17,000 acres) by 1995, an increase from 130 hectares in the middle of the 20th century.[55]

In 1983, a hotel and conference center was developed at the north end of the Corniche. The 15-story Sheraton hotel structure in this center would serve as the tallest structure in Doha until the 1990s.[55] In 1993, the Qatar Open became the first major sports event to be hosted in the city.[56] Two years later, Qatar stepped in to host the FIFA World Youth Championship, with all the matches being played in Doha-based stadiums.[57]

The Al Jazeera Arabic news channel began broadcasting from Doha in 1996.[58] In the late 1990s, the government planned the construction of Education City, a 2,500 hectare Doha-based complex mainly for educational institutes.[59] Since the start of the 21st century, Doha attained significant media attention due to the hosting of several global events and the inauguration of several architectural mega-projects.[60] One of the largest projects launched by the government was The Pearl-Qatar, an artificial island off the coast of West Bay, which launched its first district in 2004.[61] In 2006, Doha was selected to host the Asian Games, leading to the development of a 250-hectare sporting complex known as Aspire Zone.[56] During this time, new cultural attractions were constructed in the city, with older ones being restored. In 2006, the government launched a restoration program to preserve Souq Waqif's architectural and historical identity. Parts constructed after the 1950s were demolished whereas older structures were refurbished. The restoration was completed in 2008.[62] Katara Cultural Village was opened in the city in 2010 and has hosted the Doha Tribeca Film Festival since then.[63]

The main outcome of the World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference of 2013 was the Trade Facilitation Agreement. The agreement aims to make it easier and cheaper to import and export by improving customs procedures and making rules more transparent. Reducing global trade costs by 1% would increase worldwide income by more than US$40 billion, 65% of which would go to developing countries. The gains from the Trade Facilitation Agreement are expected to be distributed among all countries and regions, with developing landlocked countries benefiting the most.[64]

The Trade Facilitation Agreement will enter into force upon its ratification by 2/3 of WTO Members. The EU ratified the agreement in October 2015.[64]

In Bali, WTO members also agreed on a series of Doha agriculture and development issues.[64] Now modernizing the city while preserving traditions is part of the country's long-term plan, Qatar National Vision 2030.

Geography

Doha is located on the central-east portion of Qatar, bordered by the Persian Gulf on its coast. Its elevation is 10 m (33 ft).[65] Doha is highly urbanized. Land reclamation off the coast has added 400 hectares of land and 30 km of coastline.[66] Half of the 22 km2 of surface area which Hamad International Airport was constructed on was reclaimed land.[67] The geology of Doha is primarily composed of weathered unconformity on the top of the Eocene period Dammam Formation, forming dolomitic limestone.[68]

The Pearl is an artificial island in Doha with a surface area of nearly 400 ha (1,000 acres)[69] The total project has been estimated to cost $15 billion upon completion.[70] Other islands off Doha's coast include Palm Tree Island, Shrao's Island, Al Safliya Island, and Alia Island.[71]

In a 2010 survey of Doha's coastal waters conducted by the Qatar Statistics Authority, it was found that its maximum depth was 7.5 meters (25 ft) and minimum depth was 2 meters (6 ft 7 in). Furthermore, the waters had an average pH of 7.83, a salinity of 49.0 psu, an average temperature of 22.7 °C and 5.5 mg/L of dissolved oxygen.[72]

Climate

Doha has a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh) with long, extremely hot summers and short, mild to warm winters. The average high temperatures between May and September surpass 38 °C (100 °F) and often approach 45 °C (113 °F). Humidity is usually the lowest in May and June. Dewpoints can surpass 30 °C (86 °F) in the summer. Throughout the summer, the city averages almost no precipitation, and less than 20 mm (0.79 in) during other months.[73] Rainfall is scarce, at a total of 75 mm (2.95 in) per year, falling on isolated days mostly between October and March. The winter's days are relativity warm while the sun is up and cool during the night. The temperature rarely drops below 7 °C (45 °F).[74] The highest temperature recorded was 50.4 °C (122.7 °F) on 14 July 2010, which is the highest temperature to have ever been recorded in Qatar.[75]

| Climate data for Doha (1962–2013, extremes 1962–2013) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.4 (90.3) |

36.5 (97.7) |

41.5 (106.7) |

46.0 (114.8) |

47.7 (117.9) |

49.1 (120.4) |

50.4 (122.7) |

48.6 (119.5) |

46.2 (115.2) |

43.4 (110.1) |

38.0 (100.4) |

32.7 (90.9) |

50.4 (122.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22.0 (71.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

32.5 (90.5) |

38.8 (101.8) |

41.6 (106.9) |

41.9 (107.4) |

40.9 (105.6) |

38.9 (102.0) |

35.4 (95.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

33.1 (91.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.8 (64.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

32.5 (90.5) |

35.1 (95.2) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.5 (95.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

24.6 (76.3) |

20.4 (68.7) |

15.6 (60.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

11.8 (53.2) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 13.2 (0.52) |

17.1 (0.67) |

16.1 (0.63) |

8.7 (0.34) |

3.6 (0.14) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.1 (0.04) |

3.3 (0.13) |

12.1 (0.48) |

75.2 (2.95) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Doha,_Qatar||||||