A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Abbasid Caliphate | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The Abbasid Caliphate in c. 850 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Classical Arabic (central administration); various regional languages | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Abbasid | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Hereditary caliphate | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Caliph | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 750–754 | as-Saffah (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1242–1258 | al-Musta'sim (last caliph in Baghdad) | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1261–1262 | Al-Mustansir II (first caliph in Cairo) | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1508–1517 | Al-Mutawakkil III (last caliph in Cairo) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 750 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 861 | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Death of al-Radi and beginning of Later Abbasid era (940–1258) | 940 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Mongol Siege of Baghdad | 1258 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1517 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

|

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (/əˈbæsɪd, ˈæbəsɪd/; Arabic: الْخِلَافَة الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, romanized: al-Khilāfa al-ʿAbbāsiyya) was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes its name.[6] They ruled as caliphs for most of the caliphate from their capital in Baghdad in modern-day Iraq, after having overthrown the Umayyad Caliphate in the Abbasid Revolution of 750 CE (132 AH). The Abbasid Revolution had its origins and first successes in the easterly region of Khorasan, far from the bases of Umayyad power in Syria and Iraq.[7] The Abbasid Caliphate first centered its government in Kufa, modern-day Iraq, but in 762 the caliph Al-Mansur founded the city of Baghdad, near the ancient Babylonian capital city of Babylon and Persian city of Ctesiphon. Baghdad became the center of science, culture, and invention in what became known as the Golden Age of Islam. It was also during this period that Islamic manuscript production reached its height. Between the 8th and 10th centuries, Abbasid artisans pioneered and perfected manuscript techniques that became standards of the practice. This, in addition to housing several key academic institutions, including the House of Wisdom, as well as a multiethnic and multi-religious environment, garnered it an international reputation as the "Centre of Learning".

The Abbasid period was marked by dependence on Persian bureaucrats (such as the Barmakid family) for governing the territories as well as an increasing inclusion of non-Arab Muslims in the ummah (Muslim community). Persian customs were broadly adopted by the ruling elite, and they began patronage of artists and scholars.[8] Since much support for the Abbasids came from Persian converts, it was natural for the Abbasids to take over much of the Persian tradition of government.[9] Despite this initial cooperation, the Abbasids of the late 8th century had alienated both non-Arab mawali (clients)[10] and Persian bureaucrats.[11]

The political power of the caliphs was limited with the rise of the Iranian Buyids and the Seljuq Turks, who captured Baghdad in 945 and 1055, respectively. Although Abbasid leadership over the vast Islamic empire was gradually reduced to a ceremonial religious function in much of the caliphate, the dynasty retained control of its Mesopotamian domain during the rule of Caliph al-Muqtafi and extended into Iran during the reign of Caliph al-Nasir.[12] The Abbasids' age of cultural revival and fruition ended in 1258 with the sack of Baghdad by the Mongols under Hulagu Khan and the execution of al-Musta'sim. The Abbasid line of rulers, and Muslim culture in general, re-centred themselves in the Mamluk capital of Cairo in 1261. Though lacking in political power (with the brief exception of Caliph al-Musta'in of Cairo), the dynasty continued to claim religious authority until a few years after the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517,[13] with the last Abbasid caliph being Al-Mutawakkil III.[14]

History

The Abbasid caliphs were Arabs descended from Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, one of the youngest uncles of Muhammad and of the same Banu Hashim clan. The Abbasids claimed to be the true successors of Muhammad in replacing the Umayyad descendants of Banu Umayya by virtue of their closer bloodline to Muhammad.

Abbasid Revolution (750–751)

The Abbasids also distinguished themselves from the Umayyads by attacking their moral character and administration in general. According to Ira Lapidus, "The Abbasid revolt was supported largely by Arabs, mainly the aggrieved settlers of Merv with the addition of the Yemeni faction and their Mawali".[15] The Abbasids also appealed to non-Arab Muslims, known as mawali, who remained outside the kinship-based society of the Arabs and were perceived as a lower class within the Umayyad empire. Muhammad ibn 'Ali, a great-grandson of Abbas, began to campaign in Persia for the return of power to the family of Muhammad, the Hashemites, during the reign of Umar II.

During the reign of Marwan II, this opposition culminated in the rebellion of Ibrahim al-Imam, the fourth in descent from Abbas. Supported by the province of Khorasan (Eastern Persia), even though the governor opposed them, and the Shia Arabs,[6][16] he achieved considerable success, but was captured in the year 747 and died, possibly assassinated, in prison.

On 9 June 747 (15 Ramadan AH 129), Abu Muslim, rising from Khorasan, successfully initiated an open revolt against Umayyad rule, which was carried out under the sign of the Black Standard. Close to 10,000 soldiers were under Abu Muslim's command when the hostilities officially began in Merv.[17] General Qahtaba followed the fleeing governor Nasr ibn Sayyar west defeating the Umayyads at the Battle of Gorgan, the Battle of Nahāvand and finally in the Battle of Karbala, all in the year 748.[16]

Ibrahim was captured by Marwan and was killed. The quarrel was taken up by Ibrahim's brother Abdallah, known by the name of Abu al-'Abbas as-Saffah, who defeated the Umayyads in 750 in the battle near the Great Zab and was subsequently proclaimed caliph.[18] After this loss, Marwan fled to Egypt, where he was subsequently killed. The remainder of his family, barring one male, were also eliminated.[16]

Rise to power (752–775)

Immediately after their victory, as-Saffah sent his forces to Central Asia, where his forces fought against Tang expansion during the Battle of Talas. The noble Iranian family Barmakids, who were instrumental in building Baghdad, introduced the world's first recorded paper mill in the city, thus beginning a new era of intellectual rebirth in the Abbasid domain. As-Saffah focused on putting down numerous rebellions in Syria and Mesopotamia. The Byzantines conducted raids during these early distractions.[16]

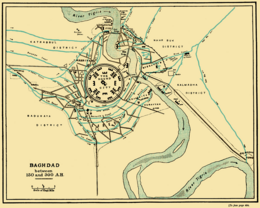

The first change made by the Abbasids under al-Mansur was to move the empire's capital from Damascus to a newly founded city. Established on the Tigris River in 762, Baghdad was closer to the Persian mawali support base of the Abbasids, and this move addressed their demand for less Arab dominance in the empire. A new position, that of the wazir, was also established to delegate central authority, and even greater authority was delegated to local emirs.[19] Al-Mansur centralised the judicial administration, and later, Harun al-Rashid established the institution of Chief Qadi to oversee it.[20]

This resulted in a more ceremonial role for many Abbasid caliphs relative to their time under the Umayyads; the viziers began to exert greater influence, and the role of the old Arab aristocracy was slowly replaced by a Persian bureaucracy.[19] During Al-Mansur's time, control of Al-Andalus was lost, and the Shia revolted and were defeated a year later at the Battle of Bakhamra.[16]

The Abbasids had depended heavily on the support of Persians[6] in their overthrow of the Umayyads. Abu al-'Abbas' successor Al-Mansur welcomed non-Arab Muslims to his court. While this helped integrate Arab and Persian cultures, it alienated many of their Arab supporters, particularly the Khorasanian Arabs who had supported them in their battles against the Umayyads. This fissure in support led to immediate problems. The Umayyads, while out of power, were not destroyed; the only surviving member of the Umayyad royal family ultimately made his way to Spain where he established himself as an independent Emir (Abd al-Rahman I, 756). In 929, Abd al-Rahman III assumed the title of Caliph, establishing Al-Andalus from Córdoba as a rival to Baghdad as the legitimate capital of the Islamic Empire.

The Umayyad empire was mostly Arab; however, the Abbasids progressively became made up of more and more converted Muslims in which the Arabs were only one of many ethnicities.[21]

In 756, Al-Mansur sent over 4,000 Arab mercenaries to assist the Chinese Tang dynasty in the An Lushan Rebellion against An Lushan. The Abbasids, or "Black Flags" as they were commonly called, were known in Tang dynasty chronicles as the hēiyī Dàshí, "The Black-robed Tazi" (黑衣大食) ("Tazi" being a borrowing from Persian Tāzī, the word for "Arab").[nb 2][nb 3][nb 4][nb 5][nb 6] Al-Rashid sent embassies to the Chinese Tang dynasty and established good relations with them.[27][nb 7][nb 8][30][31][32][33][34] After the war, these embassies remained in China[35][36][37][38][39] with Caliph Harun al-Rashid establishing an alliance with China.[27] Several embassies from the Abbasid Caliphs to the Chinese court have been recorded in the Old Book of Tang, the most important of these being those of Abul Abbas al-Saffah, the first Abbasid caliph; his successor Abu Jafar; and Harun al-Rashid.

Abbasid Golden Age (775–861)

The Abbasid leadership had to work hard in the last half of the 8th century (750–800) under several competent caliphs and their viziers to usher in the administrative changes needed to keep order of the political challenges created by the far-flung nature of the empire, and the limited communication across it.[40] It was also during this early period of the dynasty, in particular during the governance of Al-Mansur, Harun al-Rashid, and al-Ma'mun, that its reputation and power were created.[6]

Al-Mahdi restarted the fighting with the Byzantines, and his sons continued the conflict until Empress Irene pushed for peace.[16] After several years of peace, Nikephoros I broke the treaty, then fended off multiple incursions during the first decade of the 9th century. These attacks pushed into the Taurus Mountains, culminating with a victory at the Battle of Krasos and the massive invasion of 806, led by Rashid himself.[41]

Rashid's navy also proved successful, taking Cyprus. Rashid decided to focus on the rebellion of Rafi ibn al-Layth in Khorasan and died while there.[41] Military operations by the caliphate were minimal while the Byzantine Empire was fighting Abbasid rule in Syria and Anatolia, with focus shifting primarily to internal matters; Abbasid governors exerted greater autonomy and, using this increasing power, began to make their positions hereditary.[19]

At the same time, the Abbasids faced challenges closer to home. Harun al-Rashid turned on and killed most of the Barmakids, a Persian family that had grown significantly in administrative power.[43] During the same period, several factions began either to leave the empire for other lands or to take control of distant parts of the empire. Still, the reigns of al-Rashid and his sons were considered to be the apex of the Abbasids.[44]

Domestically, Harun pursued policies similar to those of his father Al-Mahdi. He released many of the Umayyads and 'Alids his brother Al-Hadi had imprisoned and declared amnesty for all political groups of the Quraysh.[45] Large scale hostilities broke out with Byzantium, and under his rule, the Abbasid Empire reached its peak.[46] However, Harun's decision to split the succession proved to be damaging to the longevity of the empire.[47]

After Rashid's death, the empire was split by a civil war between the caliph al-Amin and his brother al-Ma'mun, who had the support of Khorasan. This war ended with a two-year siege of Baghdad and the eventual death of Al-Amin in 813.[41] Al-Ma'mun ruled for 20 years of relative calm interspersed with a rebellion in Azerbaijan by the Khurramites, which was supported by the Byzantines. Al-Ma'mun was also responsible for the creation of an autonomous Khorasan, and the continued repulsing of Byzantine forays.[41]

Al-Mu'tasim gained power in 833 and his rule marked the end of the strong caliphs. He strengthened his personal army with Turkish mercenaries and promptly restarted the war with the Byzantines. Though his attempt to seize Constantinople failed when his fleet was destroyed by a storm,[48] his military excursions were generally successful, culminating with a resounding victory in the Sack of Amorium. The Byzantines responded by sacking Damietta in Egypt, and Al-Mutawakkil responded by sending his troops into Anatolia again, sacking and marauding until they were eventually annihilated in 863.[49]

Mamluks

In the 9th century, the Abbasids created an army loyal only to their caliphate, composed of non-Arab origin people, known as Mamluks.[50][51][52][53][54] This force, created in the reign of al-Ma'mun (813–833) and his brother and successor al-Mu'tasim (833–842), prevented the further disintegration of the empire. The Mamluk army, though often viewed negatively, both helped and hurt the caliphate. Early on, it provided the government with a stable force to address domestic and foreign problems. However, creation of this foreign army and al-Mu'tasim's transfer of the capital from Baghdad to Samarra created a division between the caliphate and the peoples they claimed to rule.[18] Over time, Mamluks became the ruling class and a powerful military knightly class in various Muslim societies that were controlled by previous dynastic Arab rulers. In some cases, they attained the rank of sultan, while in others they held regional power as emirs or beys. Most notably, Mamluk factions eventually created the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517) that would rule territories of Egypt and countries along the Jordan River.[55][full citation needed][56]

Fracture to autonomous dynasties (861–945)

Even by 820, the Samanids had begun the process of exercising independent authority in Transoxiana and Greater Khorasan, and the succeeding Saffarid dynasty of Iran. The Saffarids, from Khorasan, nearly seized Baghdad in 876, and the Tulunids took control of most of Syria. The trend of weakening of the central power and strengthening of the minor caliphates on the periphery continued.[44]

An exception was the 10-year period of Al-Mu'tadid's rule (r. 892–902). He brought parts of Egypt, Syria, and Khorasan back into Abbasid control. Especially after the "Anarchy at Samarra" (861–870), the Abbasid central government was weakened and centrifugal tendencies became more prominent in the caliphate's provinces. By the early 10th century, the Abbasids almost lost control of Iraq to various amirs, and the caliph al-Radi (934–941) was forced to acknowledge their power by creating the position of "Prince of Princes" (amir al-umara).[44] In addition, the power of the Mamluks steadily grew, reaching a climax when al-Radi was constrained to hand over most of the royal functions to the non-Arab Muhammad ibn Ra'iq.[18]

Al-Mustakfi had a short reign from 944 to 946, and it was during this period that the Persian faction known as the Buyids from Daylam swept into power and assumed control over the bureaucracy in Baghdad. According to the history of Miskawayh, they began distributing iqtas (fiefs in the form of tax farms) to their supporters. This period of localized secular control was to last nearly 100 years.[6] The loss of Abbasid power to the Buyids would shift as the Seljuks would take over from the Persians.[44]

At the end of the eighth century, the Abbasids found they could no longer keep together a polity from Baghdad, which had grown larger than that of Rome. In 793 the Zaydi-Shia dynasty of Idrisids set up a state from Fez in Morocco, while a family of governors under the Abbasids became increasingly independent until they founded the Aghlabid Emirate from the 830s. Al-Mu'tasim started the downward slide by using non-Muslim mercenaries in his personal army. Also during this period, officers started assassinating superiors with whom they disagreed, in particular the caliphs.[6]

By the 870s, Egypt became autonomous under Ahmad ibn Tulun. In the East, governors decreased their ties to the center as well. The Saffarids of Herat and the Samanids of Bukhara began breaking away around this time, cultivating a much more Persianate culture and statecraft. Only the central lands of Mesopotamia were under direct Abbasid control, with Palestine and the Hijaz often managed by the Tulunids. Byzantium, for its part, had begun to push Arab Muslims farther east in Anatolia.

By the 920s, North Africa was lost to the Fatimid dynasty, a Shia sect tracing its roots to Muhammad's daughter Fatimah. The Fatimid dynasty took control of Idrisid and Aghlabid domains,[44] advanced to Egypt in 969, and established their capital near Fustat in Cairo, which they built as a bastion of Shia learning and politics. By 1000 they had become the chief political and ideological challenge to Sunni Islam and the Abbasids, who by this time had fragmented into several governorships that, while recognizing caliphal authority from Baghdad, remained mostly autonomous. The caliph himself was under 'protection' of the Buyid Emirs who possessed all of Iraq and Western Iran, and were quietly Shia in their sympathies.

Outside Iraq, all the autonomous provinces slowly took on the characteristic of de facto states with hereditary rulers, armies, and revenues and operated under only nominal caliph suzerainty, which may not necessarily be reflected by any contribution to the treasury, such as the Soomro Emirs that had gained control of Sindh and ruled the entire province from their capital of Mansura.[40] Mahmud of Ghazni took the title of sultan, as opposed to the "amir" that had been in more common usage, signifying the Ghaznavid Empire's independence from caliphal authority, despite Mahmud's ostentatious displays of Sunni orthodoxy and ritual submission to the caliph. In the 11th century, the loss of respect for the caliphs continued, as some Islamic rulers no longer mentioned the caliph's name in the Friday khutba, or struck it off their coinage.[40]

The Isma'ili Fatimid dynasty of Cairo contested the Abbasids for the titular authority of the Islamic ummah. They commanded some support in the Shia sections of Baghdad (such as Karkh), although Baghdad was the city most closely connected to the caliphate, even in the Buyid and Seljuq eras. The challenge of the Fatimids only ended with their downfall in the 12th century.

Buyid and Seljuq control (945–1118)

Despite the power of the Buyid amirs, the Abbasids retained a highly ritualized court in Baghdad, as described by the Buyid bureaucrat Hilal al-Sabi', and they retained a certain influence over Baghdad as well as religious life. As Buyid power waned with the rule of Baha' al-Daula, the caliphate was able to regain some measure of strength. The caliph al-Qadir, for example, led the ideological struggle against the Shia with writings such as the Baghdad Manifesto. The caliphs kept order in Baghdad itself, attempting to prevent the outbreak of fitnas in the capital, often contending with the ayyarun.

With the Buyid dynasty on the wane, a vacuum was created that was eventually filled by the dynasty of Oghuz Turks known as the Seljuqs. By 1055, the Seljuqs had wrested control from the Buyids and Abbasids, and took temporal power.[6] When the amir and former slave Basasiri took up the Shia Fatimid banner in Baghdad in 1056–57, the caliph al-Qa'im was unable to defeat him without outside help. Toghril Beg, the Seljuq sultan, restored Baghdad to Sunni rule and took Iraq for his dynasty.

Once again, the Abbasids were forced to deal with a military power that they could not match, though the Abbasid caliph remained the titular head of the Islamic community. The succeeding sultans Alp Arslan and Malikshah, as well as their vizier Nizam al-Mulk, took up residence in Persia, but held power over the Abbasids in Baghdad. When the dynasty began to weaken in the 12th century, the Abbasids gained greater independence once again.

Revival of military strength (1118–1258)

While the caliph al-Mustarshid was the first caliph to build an army capable of meeting a Seljuk army in battle, he was nonetheless defeated and assassinated in 1135. The caliph al-Muqtafi was the first Abbasid Caliph to regain the full military independence of the caliphate, with the help of his vizier Ibn Hubayra. After nearly 250 years of subjection to foreign dynasties, he successfully defended Baghdad against the Seljuqs in the siege of Baghdad (1157), thus securing Iraq for the Abbasids. The reign of al-Nasir (d. 1225) brought the caliphate back into power throughout Iraq, based in large part on the Sufi futuwwa organizations that the caliph headed.[44] Al-Mustansir built the Mustansiriya School, in an attempt to eclipse the Seljuq-era Nizamiyya built by Nizam al Mulk.

Mongol invasion and end

In 1206, Genghis Khan established a powerful dynasty among the Mongols of central Asia. During the 13th century, this Mongol Empire conquered most of the Eurasian land mass, including both China in the east and much of the old Islamic caliphate (as well as Kievan Rus') in the west. Hulagu Khan's destruction of Baghdad in 1258 is traditionally seen as the approximate end of the Golden Age.[57]

Contemporary accounts state Mongol soldiers looted and then destroyed mosques, palaces, libraries, and hospitals. Priceless books from Baghdad's thirty-six public libraries were torn apart, the looters using their leather covers as sandals.[58] Grand buildings that had been the work of generations were burned to the ground. The House of Wisdom (the Grand Library of Baghdad), containing countless precious historical documents and books on subjects ranging from medicine to astronomy, was destroyed. Claims have been made that the Tigris ran red from the blood of the scientists and philosophers killed.[59][60] Citizens attempted to flee, but were intercepted by Mongol soldiers who killed in abundance, sparing no one, not even children.

The caliph Al-Musta'sim was captured and forced to watch as his citizens were murdered and his treasury plundered. Ironically, Mongols feared that a supernatural disaster would strike if the blood of Al-Musta'sim, a direct descendant of Muhammad's uncle Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib,[61] and the last reigning Abbasid caliph in Baghdad, was spilled. The Shia of Persia stated that no such calamity had happened after the death of Husayn ibn Ali in the Battle of Karbala; nevertheless, as a precaution and in accordance with a Mongol taboo which forbade spilling royal blood, Hulagu had Al-Musta'sim wrapped in a carpet and trampled to death by horses on 20 February 1258. The caliph's immediate family was also executed, with the lone exceptions of his youngest son who was sent to Mongolia, and a daughter who became a slave in the harem of Hulagu.[62]

Abbasid Caliphate of Cairo (1261–1517)

Similarly to how a Mamluk Army was created by the Abbasids, a Mamluk Army was created by the Egypt-based Ayyubid dynasty. These Mamluks decided to directly overthrow their masters and came to power in 1250 in what is known as the Mamluk Sultanate. In 1261, following the devastation of Baghdad by the Mongols, the Mamluk rulers of Egypt re-established the Abbasid caliphate in Cairo. The first Abbasid caliph of Cairo was Al-Mustansir. The Abbasid caliphs in Egypt continued to maintain the presence of authority, but it was confined to religious matters.[citation needed] The Abbasid caliphate of Cairo lasted until the time of Al-Mutawakkil III, who was taken away as a prisoner by Selim I to Constantinople where he had a ceremonial role. He died in 1543, following his return to Cairo.[citation needed]

Culture

Islamic Golden Age

The Abbasid historical period lasting to the Mongol conquest of Baghdad in 1258 CE is considered the Islamic Golden Age.[63] The Islamic Golden Age was inaugurated by the middle of the 8th century by the ascension of the Abbasid Caliphate and the transfer of the capital from Damascus to Baghdad.[64] The Abbasids were influenced by the Qur'anic injunctions and hadith, such as "the ink of a scholar is more holy than the blood of a martyr", stressing the value of knowledge. During this period the Muslim world became an intellectual center for science, philosophy, medicine and education as[64] the Abbasids championed the cause of knowledge and established the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, where both Muslim and non-Muslim scholars sought to translate and gather all the world's knowledge into Arabic.[64] Many classic works of antiquity that would otherwise have been lost were translated into Arabic and Persian and later in turn translated into Turkish, Hebrew and Latin.[64] During this period the Muslim world was a cauldron of cultures which collected, synthesized and significantly advanced the knowledge gained from the Roman, Chinese, Indian, Persian, Egyptian, North African, Ancient Greek and Medieval Greek civilizations.[64] According to Huff, "n virtually every field of endeavor—in astronomy, alchemy, mathematics, medicine, optics and so forth—the Caliphate's scientists were in the forefront of scientific advance."[65]

Literature

The best-known fiction from the Islamic world is One Thousand and One Nights, a collection of fantastical folk tales, legends and parables compiled primarily during the Abbasid era. The collection is recorded as having originated from an Arabic translation of a Sassanian-era Persian prototype, with likely origins in Indian literary traditions. Stories from Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, and Egyptian folklore and literature were later incorporated. The epic is believed to have taken shape in the 10th century and reached its final form by the 14th century; the number and type of tales have varied from one manuscript to another.[67] All Arabian fantasy tales were often called "Arabian Nights" when translated into English, regardless of whether they appeared in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights.[67] This epic has been influential in the West since it was translated in the 18th century, first by Antoine Galland.[68] Many imitations were written, especially in France.[69] Various characters from this epic have themselves become cultural icons in Western culture, such as Aladdin, Sinbad and Ali Baba.

A famous example of Islamic poetry on romance was Layla and Majnun, an originally Arabic story which was further developed by Iranian, Azerbaijani and other poets in the Persian, Azerbaijani, and Turkish languages.[70] It is a tragic story of undying love much like the later Romeo and Juliet.[citation needed]

Arabic poetry reached its greatest height in the Abbasid era, especially before the loss of central authority and the rise of the Persianate dynasties. Writers like Abu Tammam and Abu Nuwas were closely connected to the caliphal court in Baghdad during the early 9th century, while others such as al-Mutanabbi received their patronage from regional courts.

Under Harun al-Rashid, Baghdad was renowned for its bookstores, which proliferated after the making of paper was introduced. Chinese papermakers had been among those taken prisoner by the Arabs at the Battle of Talas in 751. As prisoners of war, they were dispatched to Samarkand, where they helped set up the first Arab paper mill. In time, paper replaced parchment as the medium for writing, and the production of books greatly increased. These events had an academic and societal impact that could be broadly compared to the introduction of the printing press in the West. Paper aided in communication and record-keeping, it also brought a new sophistication and complexity to businesses, banking, and the civil service. In 794, Jafa al-Barmak built the first paper mill in Baghdad, and from there the technology circulated. Harun required that paper be employed in government dealings, since something recorded on paper could not easily be changed or removed, and eventually, an entire street in Baghdad's business district was dedicated to selling paper and books.[71]

Philosophy

One of the common definitions for "Islamic philosophy" is "the style of philosophy produced within the framework of Islamic culture".[72] Islamic philosophy, in this definition is neither necessarily concerned with religious issues, nor is exclusively produced by Muslims.[72] Their works on Aristotle were a key step in the transmission of learning from ancient Greeks to the Islamic world and the West. They often corrected the philosopher, encouraging a lively debate in the spirit of ijtihad. They also wrote influential original philosophical works, and their thinking was incorporated into Christian philosophy during the Middle Ages, notably by Thomas Aquinas.[73]

Three speculative thinkers, al-Kindi, al-Farabi, and Avicenna, combined Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism with other ideas introduced through Islam, and Avicennism was later established as a result. Other influential Abbasid philosophers include al-Jahiz, and Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen).

Architecture

As power shifted from the Umayyads to the Abbasids, the architectural styles changed also, from Greco-Roman tradition (which features elements of Hellenistic and Roman representative style) to Eastern tradition which retained their independent architectural traditions from Mesopotamia and Persia.[74] The Abbasid architecture was particularly influenced by Sasanian architecture, which in turn featured elements present since ancient Mesopotamia.[75][76] The Christian styles evolved into a style based more on the Sasanian Empire, utilizing mud bricks and baked bricks with carved stucco.[77] Another major development was the creation or vast enlargement of cities as they were turned into the capital of the empire, beginning with the creation of Baghdad in 762, which was planned as a walled city with four gates, and a mosque and palace in the center. Al-Mansur, who was responsible for the creation of Baghdad, also planned the city of Raqqa, along the Euphrates. Finally, in 836, al-Mu'tasim moved the capital to a new site that he created along the Tigris, called Samarra. This city saw 60 years of work, with race-courses and game preserves to add to the atmosphere.[77] Due to the dry remote nature of the environment, some of the palaces built in this era were isolated havens. Al-Ukhaidir Fortress is a fine example of this type of building, which has stables, living quarters, and a mosque, all surrounding inner courtyards.[77] Other mosques of this era, such as the Great Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia, while ultimately built during the Umayyad dynasty, were substantially renovated in the 9th century. These renovations, so extensive as to ostensibly be rebuilds, were in the furthest reaches of the Muslim world, in an area that the Aghlabids controlled; however, the styles utilized were mainly Abbasid.[78] In Egypt, Ahmad Ibn Tulun commissioned the Ibn Tulun Mosque, completed in 879, that is based on the style of Samarra and is now one of the best-preserved Abbasid-style mosques from this period.[79] Mesopotamia only has one surviving mausoleum from this era, in Samarra. This octagonal dome is the final resting place of al-Muntasir.[80] Other architectural innovations and styles were few, such as the four-centered arch, and a dome erected on squinches. Unfortunately, much was lost due to the ephemeral nature of the stucco and luster tiles.[80]

Foundation of Baghdad

The caliph al-Mansur founded the epicenter of the empire, Baghdad, in 762 CE, as a means of disassociating his dynasty from that of the preceding Umayyads (centered at Damascus) and the rebellious cities of Kufa and Basrah. Mesopotamia was an ideal locale for a capital city due to its high agricultural output, access to the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers (allowing for trade and communication across the region), central locale between the corners of the vast empire (stretching from Egypt to Afghanistan) and access to the Silk Road and Indian Ocean trade routes, all key reasons as to why the region has hosted important capital cities such as Ur, Babylon, Nineveh and Ctesiphon and was later desired by the British Empire as an outpost by which to maintain access to India.[81] The city was organized in a circular fashion next to the Tigris River, with massive brick walls being constructed in successive rings around the core by a workforce of 100,000 with four huge gates (named Kufa, Basrah, Khorasan and Syria). The central enclosure of the city contained Mansur's palace of 360,000 square feet (33,000 m2) in area and the great mosque of Baghdad, encompassing 90,000 square feet (8,400 m2). Travel across the Tigris and the network of waterways allowing the drainage of the Euphrates into the Tigris was facilitated by bridges and canals servicing the population.[82]

Glass and crystal

The Near East has, since Roman times, been recognized as a center of quality glassware and crystal. 9th-century finds from Samarra show styles similar to Sassanian forms. The types of objects made were bottles, flasks, vases, and cups intended for domestic use, with decorations including molded flutes, honeycomb patterns, and inscriptions.[83] Other styles seen that may not have come from the Sassanians were stamped items. These were typically round stamps, such as medallions or disks with animals, birds, or Kufic inscriptions. Colored lead glass, typically blue or green, has been found in Nishapur, along with prismatic perfume bottles. Finally, cut glass may have been the high point of Abbasid glass-working, decorated with floral and animal designs.[84]

Painting

Early Abbasid painting has not survived in great quantities, and is sometimes harder to differentiate; however, Samarra provides good examples, as it was built by the Abbasids and abandoned 56 years later. The walls of the principal rooms of the palace that have been excavated show wall paintings and lively carved stucco dadoes. The style is obviously adopted with little variation from Sassanian art, bearing not only similar styles, with harems, animals, and dancing people, all enclosed in scrollwork, but the garments are also Persian.[85] Nishapur had its own school of painting. Excavations at Nishapur show both monochromatic and polychromatic artwork from the 8th and 9th centuries. One famous piece of art consists of hunting nobles with falcons and on horseback, in full regalia; the clothing identifies them as Tahirid, which was, again, a sub-dynasty of the Abbasids. Other styles are of vegetation, and fruit in nice colors on a four-foot high dedo.[85]

Pottery

Whereas painting and architecture were not areas of strength for the Abbasid dynasty, pottery was a different story. Islamic culture as a whole, and the Abbasids in particular, were at the forefront of new ideas and techniques. Some examples of their work were pieces engraved with decorations and then colored with yellow-brown, green, and purple glazes. Designs were diverse with geometric patterns, Kufic lettering, and arabesque scrollwork, along with rosettes, animals, birds, and humans.[89] Abbasid pottery from the 8th and 9th centuries has been found throughout the region, as far as Cairo. These were generally made with a yellow clay and fired multiple times with separate glazes to produce metallic luster in shades of gold, brown, or red. By the 9th century, the potters had mastered their techniques and their decorative designs could be divided into two styles. The Persian style would show animals, birds, and humans, along with Kufic lettering in gold. Pieces excavated from Samarra exceed in vibrancy and beauty any from later periods. These were predominantly being made for the caliph's use. Tiles were also made using this same technique to create both monochromatic and polychromatic lusterware tiles.[90]

Textiles

Egypt being a center of the textile industry was part of Abbasid cultural advancement. Copts were employed in the textile industry and produced linens and silks. Tinnis was famous for its factories and had over 5,000 looms. Examples of textiles were kasab, a fine linen for turbans, and badana for upper-class garments. The kiswah for the kaaba in Mecca was made in a town named Tuna near Tinnis. Fine silk was also made in Dabik and Damietta.[91] Of particular interest are stamped and inscribed fabrics, which used not only inks but also liquid gold. Some of the finer pieces were colored in such a manner as to require six separate stamps to achieve the proper design and color. This technology spread to Europe eventually.[92]

Clothing

The Abbasid period saw a large fashion development throughout its existence. While the development of fashion began during the Umayyad period, its genuine cosmopolitan styles and influence were realized at their finest during Abbasid rule. Fashion was a thriving industry during the Abbasid period that was also strictly regulated either by law or through the accepted elements of style. Among the higher classes, appearance became a concern and they started to care about appearance and fashion. Several new garments and fabrics were introduced into common use and no longer observed pious distaste for materials such as silk and satins. The rise of the Persian secretarial class had a large influence over the development of fashion and the Abbasids were highly influenced by the older Persian Court dress elements. For example, the caliph al-Muʿtasim was reportedly notable for his desire to imitate Persian kings by wearing a turban over a soft cap which was later adopted by other Abbasid rulers and called it the "muʿtasimi" in his honor.

The Abbasids wore many layers of garments. Fabrics used for the clothing seemed to have included wool, linen, brocades, or silk the clothing of the poorer classes was made out of cheaper materials, such as wool, and had less fabric. This also meant they wouldn't be able to afford the variety of garments that the elite classes wore. Elegant women would not wear black, green, red, or pink, except for fabrics that naturally had those colors, such as red silk. Women's clothing would be perfumed with musk, sandalwood, hyacinth or ambergris, but no other scents. Footwear included furry Cambay shoes, boots of the style of Persian ladies, and curved shoes.

Caliph al-Mansur was credited with making his court and the Abbasid high-ranking officials wear honorific robes of the color black for various ceremonial affairs and events which became the official color of the caliphate. This was acknowledged in China and Byzantium who called the Abbasids the "black-robed ones". But despite the color black being common during the caliphate, many color dyes existed and it was made sure that colors would not clash. Notably, the color yellow needed to be avoided when wearing colored clothing.[94]

Abbasid Caliphs wore elegant kaftans, a Persian robe made from silver or gold brocade and buttons in the front of the sleeves.[95] Caliph al-Muqtaddir wore a kaftan from silver brocade Tustari silk and his son one made from Byzantine silk richly decorated or ornamented with figures. The kaftan was spread far and wide by the Abbasids and made known throughout the Arab world.[96] In the 830s, Emperor Theophilus, went about à l'arabe in kaftans and turbans. Even as far as the streets of Ghuangzhou during the era of Tang dynasty, the Persian kaftan was in fashion.[97]

Manuscripts

The production of Qur'anic manuscripts flourished under the Abbasid Caliphate primarily between the late 8th and early 10th century. During this period, copies of the Qur'an were frequently commissioned for members of the Abbasid court and the wealthy elite in Muslim society.[98] With the increased dissemination of the Qur'an also came the growth of Arabic calligraphy, bookbinding techniques, and illumination styles. This expansion and establishment of the book arts culminated in a formative period of the Islamic manuscript tradition.[98][99]

Calligraphyedit

The earliest style of calligraphy used for Abbasid Qur'ans was known as the Kufic script—a script distinguished by precise, angular letters, generous spacing, horizontal extension of letters at the baseline and an emphasis on geometric proportion.[100] Qur'ans copied in this script were typically formatted in a horizontal manner and were written on parchment. Qur'ans of this variety were most popular in the second half of the 8th century.[100]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Caliphs_of_BaghdadText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk