A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Laws of Form (hereinafter LoF) is a book by G. Spencer-Brown, published in 1969, that straddles the boundary between mathematics and philosophy. LoF describes three distinct logical systems:

- The "primary arithmetic" (described in Chapter 4 of LoF), whose models include Boolean arithmetic;

- The "primary algebra" (Chapter 6 of LoF), whose models include the two-element Boolean algebra (hereinafter abbreviated 2), Boolean logic, and the classical propositional calculus;

- "Equations of the second degree" (Chapter 11), whose interpretations include finite automata and Alonzo Church's Restricted Recursive Arithmetic (RRA).

"Boundary algebra" is Meguire's (2011)[1] term for the union of the primary algebra and the primary arithmetic. Laws of Form sometimes loosely refers to the "primary algebra" as well as to LoF.

The book

The preface states that the work was first explored in 1959, and Spencer Brown cites Bertrand Russell as being supportive of his endeavour. He also thanks J. C. P. Miller of University College London for helping with the proof reading and offering other guidance. In 1963 Spencer Brown was invited by Harry Frost, staff lecturer in the physical sciences at the department of Extra-Mural Studies of the University of London to deliver a course on the mathematics of logic.

LoF emerged from work in electronic engineering its author did around 1960, and from subsequent lectures on mathematical logic he gave under the auspices of the University of London's extension program. LoF has appeared in several editions. The second series of editions appeared in 1972 with the "Preface to the First American Edition", which emphasised the use of self-referential paradoxes,[2] and the most recent being a 1997 German translation. LoF has never gone out of print.

LoF's mystical and declamatory prose and its love of paradox make it a challenging read for all. Spencer-Brown was influenced by Wittgenstein and R. D. Laing. LoF also echoes a number of themes from the writings of Charles Sanders Peirce, Bertrand Russell, and Alfred North Whitehead.

The work has had curious effects on some classes of its readership; for example, on obscure grounds, it has been claimed that the entire book is written in an operational way, giving instructions to the reader instead of telling them what "is", and that in accordance with G. Spencer-Brown's interest in paradoxes, the only sentence that makes a statement that something is, is the statement which says no such statements are used in this book.[3] Furthermore, the claim asserts that except for this one sentence the book can be seen as an example of E-Prime. What prompted such a claim, is obscure, either in terms of incentive, logical merit, or as a matter of fact, because the book routinely and naturally uses the verb to be throughout, and in all its grammatical forms, as may be seen both in the original and in quotes shown below.[4]

Reception

Ostensibly a work of formal mathematics and philosophy, LoF became something of a cult classic: it was praised by Heinz von Foerster when he reviewed it for the Whole Earth Catalog.[5] Those who agree point to LoF as embodying an enigmatic "mathematics of consciousness", its algebraic symbolism capturing an (perhaps even "the") implicit root of cognition: the ability to "distinguish". LoF argues that primary algebra reveals striking connections among logic, Boolean algebra, and arithmetic, and the philosophy of language and mind.

Stafford Beer wrote in a review for Nature, "When one thinks of all that Russell went through sixty years ago, to write the Principia, and all we his readers underwent in wrestling with those three vast volumes, it is almost sad".[6]

Banaschewski (1977)[7] argues that the primary algebra is nothing but new notation for Boolean algebra. Indeed, the two-element Boolean algebra 2 can be seen as the intended interpretation of the primary algebra. Yet the notation of the primary algebra:

- Fully exploits the duality characterizing not just Boolean algebras but all lattices;

- Highlights how syntactically distinct statements in logic and 2 can have identical semantics;

- Dramatically simplifies Boolean algebra calculations, and proofs in sentential and syllogistic logic.

Moreover, the syntax of the primary algebra can be extended to formal systems other than 2 and sentential logic, resulting in boundary mathematics (see § Related work below).

LoF has influenced, among others, Heinz von Foerster, Louis Kauffman, Niklas Luhmann, Humberto Maturana, Francisco Varela and William Bricken. Some of these authors have modified the primary algebra in a variety of interesting ways.

LoF claimed that certain well-known mathematical conjectures of very long standing, such as the four color theorem, Fermat's Last Theorem, and the Goldbach conjecture, are provable using extensions of the primary algebra. Spencer-Brown eventually circulated a purported proof of the four color theorem, but it met with skepticism.[8]

The form (Chapter 1)

The symbol:

Also called the "mark" or "cross", is the essential feature of the Laws of Form. In Spencer-Brown's inimitable and enigmatic fashion, the Mark symbolizes the root of cognition, i.e., the dualistic Mark indicates the capability of differentiating a "this" from "everything else but this".

In LoF, a Cross denotes the drawing of a "distinction", and can be thought of as signifying the following, all at once:

- The act of drawing a boundary around something, thus separating it from everything else;

- That which becomes distinct from everything by drawing the boundary;

- Crossing from one side of the boundary to the other.

All three ways imply an action on the part of the cognitive entity (e.g., person) making the distinction. As LoF puts it:

"The first command:

- Draw a distinction

can well be expressed in such ways as:

- Let there be a distinction,

- Find a distinction,

- See a distinction,

- Describe a distinction,

- Define a distinction,

Or:

- Let a distinction be drawn". (LoF, Notes to chapter 2)

The counterpoint to the Marked state is the Unmarked state, which is simply nothing, the void, or the un-expressable infinite represented by a blank space. It is simply the absence of a Cross. No distinction has been made and nothing has been crossed. The Marked state and the void are the two primitive values of the Laws of Form.

The Cross can be seen as denoting the distinction between two states, one "considered as a symbol" and another not so considered. From this fact arises a curious resonance with some theories of consciousness and language. Paradoxically, the Form is at once Observer and Observed, and is also the creative act of making an observation. LoF (excluding back matter) closes with the words:

...the first distinction, the Mark and the observer are not only interchangeable, but, in the form, identical.

C. S. Peirce came to a related insight in the 1890s; see § Related work.

The primary arithmetic (Chapter 4)

The syntax of the primary arithmetic goes as follows. There are just two atomic expressions:

There are two inductive rules:

- A Cross

may be written over any expression;

may be written over any expression; - Any two expressions may be concatenated.

The semantics of the primary arithmetic are perhaps nothing more than the sole explicit definition in LoF: "Distinction is perfect continence".

Let the "unmarked state" be a synonym for the void. Let an empty Cross denote the "marked state". To cross is to move from one value, the unmarked or marked state, to the other. We can now state the "arithmetical" axioms A1 and A2, which ground the primary arithmetic (and hence all of the Laws of Form):

"A1. The law of Calling". Calling twice from a state is indistinguishable from calling once. To make a distinction twice has the same effect as making it once. For example, saying "Let there be light" and then saying "Let there be light" again, is the same as saying it once. Formally:

"A2. The law of Crossing". After crossing from the unmarked to the marked state, crossing again ("recrossing") starting from the marked state returns one to the unmarked state. Hence recrossing annuls crossing. Formally:

In both A1 and A2, the expression to the right of '=' has fewer symbols than the expression to the left of '='. This suggests that every primary arithmetic expression can, by repeated application of A1 and A2, be simplified to one of two states: the marked or the unmarked state. This is indeed the case, and the result is the expression's "simplification". The two fundamental metatheorems of the primary arithmetic state that:

- Every finite expression has a unique simplification. (T3 in LoF);

- Starting from an initial marked or unmarked state, "complicating" an expression by a finite number of repeated application of A1 and A2 cannot yield an expression whose simplification differs from the initial state. (T4 in LoF).

Thus the relation of logical equivalence partitions all primary arithmetic expressions into two equivalence classes: those that simplify to the Cross, and those that simplify to the void.

A1 and A2 have loose analogs in the properties of series and parallel electrical circuits, and in other ways of diagramming processes, including flowcharting. A1 corresponds to a parallel connection and A2 to a series connection, with the understanding that making a distinction corresponds to changing how two points in a circuit are connected, and not simply to adding wiring.

The primary arithmetic is analogous to the following formal languages from mathematics and computer science:

- A Dyck language with a null alphabet;

- The simplest context-free language in the Chomsky hierarchy;

- A rewrite system that is strongly normalizing and confluent.

The phrase "calculus of indications" in LoF is a synonym for "primary arithmetic".

The notion of canon

A concept peculiar to LoF is that of "canon". While LoF does not formally define canon, the following two excerpts from the Notes to chpt. 2 are apt:

The more important structures of command are sometimes called canons. They are the ways in which the guiding injunctions appear to group themselves in constellations, and are thus by no means independent of each other. A canon bears the distinction of being outside (i.e., describing) the system under construction, but a command to construct (e.g., 'draw a distinction'), even though it may be of central importance, is not a canon. A canon is an order, or set of orders, to permit or allow, but not to construct or create.

...the primary form of mathematical communication is not description but injunction... Music is a similar art form, the composer does not even attempt to describe the set of sounds he has in mind, much less the set of feelings occasioned through them, but writes down a set of commands which, if they are obeyed by the performer, can result in a reproduction, to the listener, of the composer's original experience.

These excerpts relate to the distinction in metalogic between the object language, the formal language of the logical system under discussion, and the metalanguage, a language (often a natural language) distinct from the object language, employed to exposit and discuss the object language. The first quote seems to assert that the canons are part of the metalanguage. The second quote seems to assert that statements in the object language are essentially commands addressed to the reader by the author. Neither assertion holds in standard metalogic.

The primary algebra (Chapter 6)

Syntax

Given any valid primary arithmetic expression, insert into one or more locations any number of Latin letters bearing optional numerical subscripts; the result is a primary algebra formula. Letters so employed in mathematics and logic are called variables. A primary algebra variable indicates a location where one can write the primitive value ![]() or its complement

or its complement ![]() . Multiple instances of the same variable denote multiple locations of the same primitive value.

. Multiple instances of the same variable denote multiple locations of the same primitive value.

Rules governing logical equivalence

The sign '=' may link two logically equivalent expressions; the result is an equation. By "logically equivalent" is meant that the two expressions have the same simplification. Logical equivalence is an equivalence relation over the set of primary algebra formulas, governed by the rules R1 and R2. Let "C" and "D" be formulae each containing at least one instance of the subformula A:

- R1, Substitution of equals. Replace one or more instances of A in C by B, resulting in E. If A=B, then C=E.

- R2, Uniform replacement. Replace all instances of A in C and D with B. C becomes E and D becomes F. If C=D, then E=F. Note that A=B is not required.

R2 is employed very frequently in primary algebra demonstrations (see below), almost always silently. These rules are routinely invoked in logic and most of mathematics, nearly always unconsciously.

The primary algebra consists of equations, i.e., pairs of formulae linked by an infix operator '='. R1 and R2 enable transforming one equation into another. Hence the primary algebra is an equational formal system, like the many algebraic structures, including Boolean algebra, that are varieties. Equational logic was common before Principia Mathematica (e.g., Peirce,1,2,3 Johnson 1892), and has present-day advocates (Gries and Schneider 1993).

Conventional mathematical logic consists of tautological formulae, signalled by a prefixed turnstile. To denote that the primary algebra formula A is a tautology, simply write "A =![]() ". If one replaces '=' in R1 and R2 with the biconditional, the resulting rules hold in conventional logic. However, conventional logic relies mainly on the rule modus ponens; thus conventional logic is ponential. The equational-ponential dichotomy distills much of what distinguishes mathematical logic from the rest of mathematics.

". If one replaces '=' in R1 and R2 with the biconditional, the resulting rules hold in conventional logic. However, conventional logic relies mainly on the rule modus ponens; thus conventional logic is ponential. The equational-ponential dichotomy distills much of what distinguishes mathematical logic from the rest of mathematics.

Initials

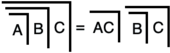

An initial is a primary algebra equation verifiable by a decision procedure and as such is not an axiom. LoF lays down the initials:

|

|

= . |

The absence of anything to the right of the "=" above, is deliberate.

|

|

C | = |

|

. |

J2 is the familiar distributive law of sentential logic and Boolean algebra.

Another set of initials, friendlier to calculations, is:

|

|

A | = | A. |

|

|

= |

|

. |

|

A |

|

= | A |

|

. |

It is thanks to C2 that the primary algebra is a lattice. By virtue of J1a, it is a complemented lattice whose upper bound is ![]() . By J0,

. By J0, ![]() is the corresponding lower bound and identity element. J0 is also an algebraic version of A2 and makes clear the sense in which

is the corresponding lower bound and identity element. J0 is also an algebraic version of A2 and makes clear the sense in which ![]() aliases with the blank page.

aliases with the blank page.

T13 in LoF generalizes C2 as follows. Any primary algebra (or sentential logic) formula B can be viewed as an ordered tree with branches. Then:

T13: A subformula A can be copied at will into any depth of B greater than that of A, as long as A and its copy are in the same branch of B. Also, given multiple instances of A in the same branch of B, all instances but the shallowest are redundant.

While a proof of T13 would require induction, the intuition underlying it should be clear.

C2 or its equivalent is named:

- "Generation" in LoF;

- "Exclusion" in Johnson (1892);

- "Pervasion" in the work of William Bricken.

Perhaps the first instance of an axiom or rule with the power of C2 was the "Rule of (De)Iteration", combining T13 and AA=A, of C. S. Peirce's existential graphs.

LoF asserts that concatenation can be read as commuting and associating by default and hence need not be explicitly assumed or demonstrated. (Peirce made a similar assertion about his existential graphs.) Let a period be a temporary notation to establish grouping. That concatenation commutes and associates may then be demonstrated from the:

- Initial AC.D=CD.A and the consequence AA=A (Byrne 1946). This result holds for all lattices, because AA=A is an easy consequence of the absorption law, which holds for all lattices;

- Initials AC.D=AD.C and J0. Since J0 holds only for lattices with a lower bound, this method holds only for bounded lattices (which include the primary algebra and 2). Commutativity is trivial; just set A=

. Associativity: AC.D = CA.D = CD.A = A.CD.

. Associativity: AC.D = CA.D = CD.A = A.CD.

Having demonstrated associativity, the period can be discarded.

The initials in Meguire (2011) are AC.D=CD.A, called B1; B2, J0 above; B3, J1a above; and B4, C2. By design, these initials are very similar to the axioms for an abelian group, G1-G3 below.

Proof theory

The primary algebra contains three kinds of proved assertions:

- Consequence is a primary algebra equation verified by a demonstration. A demonstration consists of a sequence of steps, each step justified by an initial or a previously demonstrated consequence.

- Theorem is a statement in the metalanguage verified by a proof, i.e., an argument, formulated in the metalanguage, that is accepted by trained mathematicians and logicians.

- Initial, defined above. Demonstrations and proofs invoke an initial as if it were an axiom.

The distinction between consequence and theorem holds for all formal systems, including mathematics and logic, but is usually not made explicit. A demonstration or decision procedure can be carried out and verified by computer. The proof of a theorem cannot be.

Let A and B be primary algebra formulas. A demonstration of A=B may proceed in either of two ways:

- Modify A in steps until B is obtained, or vice versa;

- Simplify both

and

and  to

to  . This is known as a "calculation".

. This is known as a "calculation".

Once A=B has been demonstrated, A=B can be invoked to justify steps in subsequent demonstrations. primary algebra demonstrations and calculations often require no more than J1a, J2, C2, and the consequences ![]() (C3 in LoF),

(C3 in LoF), ![]() (C1), and AA=A (C5).

(C1), and AA=A (C5).

The consequence  , C7' in LoF, enables an algorithm, sketched in LoFs proof of T14, that transforms an arbitrary primary algebra formula to an equivalent formula whose depth does not exceed two. The result is a normal form, the primary algebra analog of the conjunctive normal form. LoF (T14–15) proves the primary algebra analog of the well-known Boolean algebra theorem that every formula has a normal form.

, C7' in LoF, enables an algorithm, sketched in LoFs proof of T14, that transforms an arbitrary primary algebra formula to an equivalent formula whose depth does not exceed two. The result is a normal form, the primary algebra analog of the conjunctive normal form. LoF (T14–15) proves the primary algebra analog of the well-known Boolean algebra theorem that every formula has a normal form.

Let A be a subformula of some formula B. When paired with C3, J1a can be viewed as the closure condition for calculations: B is a tautology if and only if A and (A) both appear in depth 0 of B. A related condition appears in some versions of natural deduction. A demonstration by calculation is often little more than:

- Invoking T13 repeatedly to eliminate redundant subformulae;

- Erasing any subformulae having the form

.

.

The last step of a calculation always invokes J1a.

LoF includes elegant new proofs of the following standard metatheory:

- Completeness: all primary algebra consequences are demonstrable from the initials (T17).

- Independence: J1 cannot be demonstrated from J2 and vice versa (T18).

That sentential logic is complete is taught in every first university course in mathematical logic. But university courses in Boolean algebra seldom mention the completeness of 2.

Interpretations

If the Marked and Unmarked states are read as the Boolean values 1 and 0 (or True and False), the primary algebra interprets 2 (or sentential logic). LoF shows how the primary algebra can interpret the syllogism. Each of these interpretations is discussed in a subsection below. Extending the primary algebra so that it could interpret standard first-order logic has yet to be done, but Peirce's beta existential graphs suggest that this extension is feasible.

Two-element Boolean algebra 2

The primary algebra is an elegant minimalist notation for the two-element Boolean algebra 2. Let:

- One of Boolean join (+) or meet (×) interpret concatenation;

- The complement of A interpret

- 0 (1) interpret the empty Mark if join (meet) interprets concatenation (because a binary operation applied to zero operands may be regarded as being equal to the identity element of that operation; or to put it in another way, an operand that is missing could be regarded as acting by default like the identity element).

If join (meet) interprets AC, then meet (join) interprets . Hence the primary algebra and 2 are isomorphic but for one detail: primary algebra complementation can be nullary, in which case it denotes a primitive value. Modulo this detail, 2 is a model of the primary algebra. The primary arithmetic suggests the following arithmetic axiomatization of 2: 1+1=1+0=0+1=1=~0, and 0+0=0=~1.

The set ![]()

![]() is the Boolean domain or carrier. In the language of universal algebra, the primary algebra is the algebraic structure of type . The expressive adequacy of the Sheffer stroke points to the primary algebra also being a algebra of type . In both cases, the identities are J1a, J0, C2, and ACD=CDA. Since the primary algebra and 2 are isomorphic, 2 can be seen as a

is the Boolean domain or carrier. In the language of universal algebra, the primary algebra is the algebraic structure of type . The expressive adequacy of the Sheffer stroke points to the primary algebra also being a algebra of type . In both cases, the identities are J1a, J0, C2, and ACD=CDA. Since the primary algebra and 2 are isomorphic, 2 can be seen as a

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk