A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Agriculture |

|---|

|

|

|

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, fisheries, and forestry for food and non-food products.[1] Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to live in cities. While humans started gathering grains at least 105,000 years ago, nascent farmers only began planting them around 11,500 years ago. Sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle were domesticated around 10,000 years ago. Plants were independently cultivated in at least 11 regions of the world. In the 20th century, industrial agriculture based on large-scale monocultures came to dominate agricultural output.

As of 2021[update], small farms produce about one-third of the world's food, but large farms are prevalent.[2] The largest 1% of farms in the world are greater than 50 hectares (120 acres) and operate more than 70% of the world's farmland.[2] Nearly 40% of agricultural land is found on farms larger than 1,000 hectares (2,500 acres).[2] However, five of every six farms in the world consist of fewer than 2 hectares (4.9 acres), and take up only around 12% of all agricultural land.[2] Farms and farming greatly influence rural economics and greatly shape rural society, effecting both the direct agricultural workforce and broader businesses that support the farms and farming populations.

The major agricultural products can be broadly grouped into foods, fibers, fuels, and raw materials (such as rubber). Food classes include cereals (grains), vegetables, fruits, cooking oils, meat, milk, eggs, and fungi. Global agricultural production amounts to approximately 11 billion tonnes of food,[3] 32 million tonnes of natural fibres[4] and 4 billion m3 of wood.[5] However, around 14% of the world's food is lost from production before reaching the retail level.[6]

Modern agronomy, plant breeding, agrochemicals such as pesticides and fertilizers, and technological developments have sharply increased crop yields, but also contributed to ecological and environmental damage. Selective breeding and modern practices in animal husbandry have similarly increased the output of meat, but have raised concerns about animal welfare and environmental damage. Environmental issues include contributions to climate change, depletion of aquifers, deforestation, antibiotic resistance, and other agricultural pollution. Agriculture is both a cause of and sensitive to environmental degradation, such as biodiversity loss, desertification, soil degradation, and climate change, all of which can cause decreases in crop yield. Genetically modified organisms are widely used, although some countries ban them.

Etymology and scope

The word agriculture is a late Middle English adaptation of Latin agricultūra, from ager 'field' and cultūra 'cultivation' or 'growing'.[7] While agriculture usually refers to human activities, certain species of ant,[8][9] termite and beetle have been cultivating crops for up to 60 million years.[10] Agriculture is defined with varying scopes, in its broadest sense using natural resources to "produce commodities which maintain life, including food, fiber, forest products, horticultural crops, and their related services".[11] Thus defined, it includes arable farming, horticulture, animal husbandry and forestry, but horticulture and forestry are in practice often excluded.[11] It may also be broadly decomposed into plant agriculture, which concerns the cultivation of useful plants,[12] and animal agriculture, the production of agricultural animals.[13]

History

Origins

The development of agriculture enabled the human population to grow many times larger than could be sustained by hunting and gathering.[16] Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe,[17] and included a diverse range of taxa, in at least 11 separate centers of origin.[14] Wild grains were collected and eaten from at least 105,000 years ago.[18] In the Paleolithic Levant, 23,000 years ago, cereals cultivation of emmer, barley, and oats has been observed near the sea of Galilee.[19][20] Rice was domesticated in China between 11,500 and 6,200 BC with the earliest known cultivation from 5,700 BC,[21] followed by mung, soy and azuki beans. Sheep were domesticated in Mesopotamia between 13,000 and 11,000 years ago.[22] Cattle were domesticated from the wild aurochs in the areas of modern Turkey and Pakistan some 10,500 years ago.[23] Pig production emerged in Eurasia, including Europe, East Asia and Southwest Asia,[24] where wild boar were first domesticated about 10,500 years ago.[25] In the Andes of South America, the potato was domesticated between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago, along with beans, coca, llamas, alpacas, and guinea pigs. Sugarcane and some root vegetables were domesticated in New Guinea around 9,000 years ago. Sorghum was domesticated in the Sahel region of Africa by 7,000 years ago. Cotton was domesticated in Peru by 5,600 years ago,[26] and was independently domesticated in Eurasia. In Mesoamerica, wild teosinte was bred into maize (corn) from 10,000 to 6,000 years ago.[27][28][29] The horse was domesticated in the Eurasian Steppes around 3500 BC.[30] Scholars have offered multiple hypotheses to explain the historical origins of agriculture. Studies of the transition from hunter-gatherer to agricultural societies indicate an initial period of intensification and increasing sedentism; examples are the Natufian culture in the Levant, and the Early Chinese Neolithic in China. Then, wild stands that had previously been harvested started to be planted, and gradually came to be domesticated.[31][32][33]

Civilizations

In Eurasia, the Sumerians started to live in villages from about 8,000 BC, relying on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and a canal system for irrigation. Ploughs appear in pictographs around 3,000 BC; seed-ploughs around 2,300 BC. Farmers grew wheat, barley, vegetables such as lentils and onions, and fruits including dates, grapes, and figs.[36] Ancient Egyptian agriculture relied on the Nile River and its seasonal flooding. Farming started in the predynastic period at the end of the Paleolithic, after 10,000 BC. Staple food crops were grains such as wheat and barley, alongside industrial crops such as flax and papyrus.[37][38] In India, wheat, barley and jujube were domesticated by 9,000 BC, soon followed by sheep and goats.[39] Cattle, sheep and goats were domesticated in Mehrgarh culture by 8,000–6,000 BC.[40][41][42] Cotton was cultivated by the 5th–4th millennium BC.[43] Archeological evidence indicates an animal-drawn plough from 2,500 BC in the Indus Valley civilisation.[44]

In China, from the 5th century BC, there was a nationwide granary system and widespread silk farming.[45] Water-powered grain mills were in use by the 1st century BC,[46] followed by irrigation.[47] By the late 2nd century, heavy ploughs had been developed with iron ploughshares and mouldboards.[48][49] These spread westwards across Eurasia.[50] Asian rice was domesticated 8,200–13,500 years ago – depending on the molecular clock estimate that is used[51]– on the Pearl River in southern China with a single genetic origin from the wild rice Oryza rufipogon.[52] In Greece and Rome, the major cereals were wheat, emmer, and barley, alongside vegetables including peas, beans, and olives. Sheep and goats were kept mainly for dairy products.[53][54]

In the Americas, crops domesticated in Mesoamerica (apart from teosinte) include squash, beans, and cacao.[55] Cocoa was domesticated by the Mayo Chinchipe of the upper Amazon around 3,000 BC.[56] The turkey was probably domesticated in Mexico or the American Southwest.[57] The Aztecs developed irrigation systems, formed terraced hillsides, fertilized their soil, and developed chinampas or artificial islands. The Mayas used extensive canal and raised field systems to farm swampland from 400 BC.[58][59][60][61][62] In South America agriculture may have begun about 9000 BC with the domestication of squash (Cucurbita) and other plants.[63] Coca was domesticated in the Andes, as were the peanut, tomato, tobacco, and pineapple.[55] Cotton was domesticated in Peru by 3,600 BC.[64] Animals including llamas, alpacas, and guinea pigs were domesticated there.[65] In North America, the indigenous people of the East domesticated crops such as sunflower, tobacco,[66] squash and Chenopodium.[67][68] Wild foods including wild rice and maple sugar were harvested.[69] The domesticated strawberry is a hybrid of a Chilean and a North American species, developed by breeding in Europe and North America.[70] The indigenous people of the Southwest and the Pacific Northwest practiced forest gardening and fire-stick farming. The natives controlled fire on a regional scale to create a low-intensity fire ecology that sustained a low-density agriculture in loose rotation; a sort of "wild" permaculture.[71][72][73][74] A system of companion planting called the Three Sisters was developed in North America. The three crops were winter squash, maize, and climbing beans.[75][76]

Indigenous Australians, long supposed to have been nomadic hunter-gatherers, practised systematic burning, possibly to enhance natural productivity in fire-stick farming.[77] Scholars have pointed out that hunter-gatherers need a productive environment to support gathering without cultivation. Because the forests of New Guinea have few food plants, early humans may have used "selective burning" to increase the productivity of the wild karuka fruit trees to support the hunter-gatherer way of life.[78]

The Gunditjmara and other groups developed eel farming and fish trapping systems from some 5,000 years ago.[79] There is evidence of 'intensification' across the whole continent over that period.[80] In two regions of Australia, the central west coast and eastern central, early farmers cultivated yams, native millet, and bush onions, possibly in permanent settlements.[33][81]

Revolution

In the Middle Ages, compared to the Roman period, agriculture in Western Europe became more focused on self-sufficiency. The agricultural population under feudalism was typically organized into manors consisting of several hundred or more acres of land presided over by a lord of the manor with a Roman Catholic church and priest.[82]

Thanks to the exchange with the Al-Andalus where the Arab Agricultural Revolution was underway, European agriculture transformed, with improved techniques and the diffusion of crop plants, including the introduction of sugar, rice, cotton and fruit trees (such as the orange).[83]

After 1492, the Columbian exchange brought New World crops such as maize, potatoes, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, and manioc to Europe, and Old World crops such as wheat, barley, rice, and turnips, and livestock (including horses, cattle, sheep and goats) to the Americas.[84]

Irrigation, crop rotation, and fertilizers advanced from the 17th century with the British Agricultural Revolution, allowing global population to rise significantly. Since 1900, agriculture in developed nations, and to a lesser extent in the developing world, has seen large rises in productivity as mechanization replaces human labor, and assisted by synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and selective breeding. The Haber-Bosch method allowed the synthesis of ammonium nitrate fertilizer on an industrial scale, greatly increasing crop yields and sustaining a further increase in global population.[85][86]

Modern agriculture has raised or encountered ecological, political, and economic issues including water pollution, biofuels, genetically modified organisms, tariffs and farm subsidies, leading to alternative approaches such as the organic movement.[87][88] Unsustainable farming practices in North America led to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.[89]

Types

Pastoralism involves managing domesticated animals. In nomadic pastoralism, herds of livestock are moved from place to place in search of pasture, fodder, and water. This type of farming is practised in arid and semi-arid regions of Sahara, Central Asia and some parts of India.[90]

In shifting cultivation, a small area of forest is cleared by cutting and burning the trees. The cleared land is used for growing crops for a few years until the soil becomes too infertile, and the area is abandoned. Another patch of land is selected and the process is repeated. This type of farming is practiced mainly in areas with abundant rainfall where the forest regenerates quickly. This practice is used in Northeast India, Southeast Asia, and the Amazon Basin.[91]

Subsistence farming is practiced to satisfy family or local needs alone, with little left over for transport elsewhere. It is intensively practiced in Monsoon Asia and South-East Asia.[92] An estimated 2.5 billion subsistence farmers worked in 2018, cultivating about 60% of the earth's arable land.[93]

Intensive farming is cultivation to maximise productivity, with a low fallow ratio and a high use of inputs (water, fertilizer, pesticide and automation). It is practiced mainly in developed countries.[94][95]

Contemporary agriculture

Status

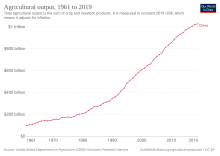

From the twentieth century onwards, intensive agriculture increased crop productivity. It substituted synthetic fertilizers and pesticides for labour, but caused increased water pollution, and often involved farm subsidies. Soil degradation and diseases such as stem rust are major concerns globally;[96] approximately 40% of the world's agricultural land is seriously degraded.[97][98] In recent years there has been a backlash against the environmental effects of conventional agriculture, resulting in the organic, regenerative, and sustainable agriculture movements.[87][99] One of the major forces behind this movement has been the European Union, which first certified organic food in 1991 and began reform of its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in 2005 to phase out commodity-linked farm subsidies,[100] also known as decoupling. The growth of organic farming has renewed research in alternative technologies such as integrated pest management, selective breeding,[101] and controlled-environment agriculture.[102][103] There are concerns about the lower yield associated with organic farming and its impact on global food security.[104] Recent mainstream technological developments include genetically modified food.[105]

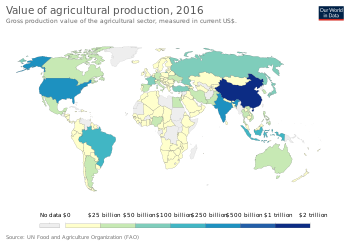

By 2015, the agricultural output of China was the largest in the world, followed by the European Union, India and the United States.[106] Economists measure the total factor productivity of agriculture, according to which agriculture in the United States is roughly 1.7 times more productive than it was in 1948.[107]

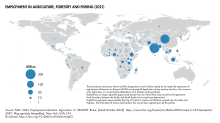

Agriculture employed 873 million people in 2021, or 27% of the global workforce, compared with 1 027 million (or 40%) in 2000. The share of agriculture in global GDP was stable at around 4% since 2000 - 2023.[108]

Despite increases in agricultural production and productivity,[109] between 702 and 828 million people were affected by hunger in 2021.[110] Food insecurity and malnutrition can be the result of conflict, climate extremes and variability and economic swings.[109] It can also be caused by a country's structural characteristics such as income status and natural resource endowments as well as its political economy.[109]

Pesticide use in agriculture went up 62% between 2000 and 2021, with the Americas accounting for half the use in 2021.[108]

The International Fund for Agricultural Development posits that an increase in smallholder agriculture may be part of the solution to concerns about food prices and overall food security, given the favorable experience of Vietnam.[111]

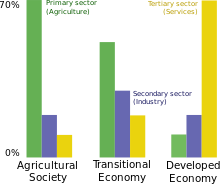

Workforce

Agriculture provides about one-quarter of all global employment, more than half in sub-Saharan Africa and almost 60 percent in low-income countries.[112] As countries develop, other jobs have historically pulled workers away from agriculture, and labour-saving innovations increase agricultural productivity by reducing labour requirements per unit of output.[113][114][115] Over time, a combination of labour supply and labour demand trends have driven down the share of population employed in agriculture.[116][117]

During the 16th century in Europe, between 55 and 75% of the population was engaged in agriculture; by the 19th century, this had dropped to between 35 and 65%.[118] In the same countries today, the figure is less than 10%.[119] At the start of the 21st century, some one billion people, or over 1/3 of the available work force, were employed in agriculture. This constitutes approximately 70% of the global employment of children, and in many countries constitutes the largest percentage of women of any industry.[120] The service sector overtook the agricultural sector as the largest global employer in 2007.[121]

In many developed countries, immigrants help fill labour shortages in high-value agriculture activities that are difficult to mechanize.[122] Foreign farm workers from mostly Eastern Europe, North Africa and South Asia constituted around one-third of the salaried agricultural workforce in Spain, Italy, Greece and Portugal in 2013.[123][124][125][126] In the United States of America, more than half of all hired farmworkers (roughly 450,000 workers) were immigrants in 2019, although the number of new immigrants arriving in the country to work in agriculture has fallen by 75 percent in recent years and rising wages indicate this has led to a major labor shortage on U.S. farms.[127][128]

Women in agriculture

Around the world, women make up a large share of the population employed in agriculture.[129] This share is growing in all developing regions except East and Southeast Asia where women already make up about 50 percent of the agricultural workforce.[129] Women make up 47 percent of the agricultural workforce in sub-Saharan Africa, a rate that has not changed significantly in the past few decades.[129] However, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) posits that the roles and responsibilities of women in agriculture may be changing – for example, from subsistence farming to wage employment, and from contributing household members to primary producers in the context of male-out-migration.[129]

In general, women account for a greater share of agricultural employment at lower levels of economic development, as inadequate education, limited access to basic infrastructure and markets, high unpaid work burden and poor rural employment opportunities outside agriculture severely limit women's opportunities for off-farm work.[130]

Women who work in agricultural production tend to do so under highly unfavourable conditions. They tend to be concentrated in the poorest countries, where alternative livelihoods are not available, and they maintain the intensity of their work in conditions of climate-induced weather shocks and in situations of conflict. Women are less likely to participate as entrepreneurs and independent farmers and are engaged in the production of less lucrative crops.[130]

The gender gap in land productivity between female- and male managed farms of the same size is 24 percent. On average, women earn 18.4 percent less than men in wage employment in agriculture; this means that women receive 82 cents for every dollar earned by men. Progress has been slow in closing gaps in women's access to irrigation and in ownership of livestock, too.[130]

Women in agriculture still have significantly less access than men to inputs, including improved seeds, fertilizers and mechanized equipment. On a positive note, the gender gap in access to mobile internet in low- and middle-income countries fell from 25 percent to 16 percent between 2017 and 2021, and the gender gap in access to bank accounts narrowed from 9 to 6 percentage points. Women are as likely as men to adopt new technologies when the necessary enabling factors are put in place and they have equal access to complementary resources.[130]

Safety

Agriculture, specifically farming, remains a hazardous industry, and farmers worldwide remain at high risk of work-related injuries, lung disease, noise-induced hearing loss, skin diseases, as well as certain cancers related to chemical use and prolonged sun exposure. On industrialized farms, injuries frequently involve the use of agricultural machinery, and a common cause of fatal agricultural injuries in developed countries is tractor rollovers.[131] Pesticides and other chemicals used in farming can be hazardous to worker health, and workers exposed to pesticides may experience illness or have children with birth defects.[132] As an industry in which families commonly share in work and live on the farm itself, entire families can be at risk for injuries, illness, and death.[133] Ages 0–6 May be an especially vulnerable population in agriculture;[134] common causes of fatal injuries among young farm workers include drowning, machinery and motor accidents, including with all-terrain vehicles.[133][134][135]

The International Labour Organization considers agriculture "one of the most hazardous of all economic sectors".[120] It estimates that the annual work-related death toll among agricultural employees is at least 170,000, twice the average rate of other jobs. In addition, incidences of death, injury and illness related to agricultural activities often go unreported.[136] The organization has developed the Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention, 2001, which covers the range of risks in the agriculture occupation, the prevention of these risks and the role that individuals and organizations engaged in agriculture should play.[120]

In the United States, agriculture has been identified by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health as a priority industry sector in the National Occupational Research Agenda to identify and provide intervention strategies for occupational health and safety issues.[137][138] In the European Union, the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work has issued guidelines on implementing health and safety directives in agriculture, livestock farming, horticulture, and forestry.[139] The Agricultural Safety and Health Council of America (ASHCA) also holds a yearly summit to discuss safety.[140]

Production

Overall production varies by country as listed.

| Largest countries by agricultural output (in nominal terms) according to IMF and CIA World Factbook, at peak level as of 2018 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest countries by agricultural output according to UNCTAD at 2005 constant prices and exchange rates, 2015[106] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

Crop cultivation systems

Cropping systems vary among farms depending on the available resources and constraints; geography and climate of the farm; government policy; economic, social and political pressures; and the philosophy and culture of the farmer.[142][143]

Shifting cultivation (or slash and burn) is a system in which forests are burnt, releasing nutrients to support cultivation of annual and then perennial crops for a period of several years.[144] Then the plot is left fallow to regrow forest, and the farmer moves to a new plot, returning after many more years (10–20). This fallow period is shortened if population density grows, requiring the input of nutrients (fertilizer or manure) and some manual pest control. Annual cultivation is the next phase of intensity in which there is no fallow period. This requires even greater nutrient and pest control inputs.[144]

Further industrialization led to the use of monocultures, when one cultivar is planted on a large acreage. Because of the low biodiversity, nutrient use is uniform and pests tend to build up, necessitating the greater use of pesticides and fertilizers.[143] Multiple cropping, in which several crops are grown sequentially in one year, and intercropping, when several crops are grown at the same time, are other kinds of annual cropping systems known as polycultures.[144]

In subtropical and arid environments, the timing and extent of agriculture may be limited by rainfall, either not allowing multiple annual crops in a year, or requiring irrigation. In all of these environments perennial crops are grown (coffee, chocolate) and systems are practiced such as agroforestry. In temperate environments, where ecosystems were predominantly grassland or prairie, highly productive annual farming is the dominant agricultural system.[144]

Important categories of food crops include cereals, legumes, forage, fruits and vegetables.[145] Natural fibers include cotton, wool, hemp, silk and flax.[146] Specific crops are cultivated in distinct growing regions throughout the world. Production is listed in millions of metric tons, based on FAO estimates.[145]