A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Barley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Genus: | Hordeum |

| Species: | H. vulgare

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hordeum vulgare | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

Barley (Hordeum vulgare), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikelets and making it much easier to harvest. Its use then spread throughout Eurasia by 2000 BC. Barley prefers relatively low temperatures to grow, and well-drained soil. It is relatively tolerant of drought and soil salinity, but is less winter-hardy than wheat or rye.

In 2022, barley was fourth among grains in quantity produced, 155 million tonnes, behind maize, wheat, and rice. Globally 70% of barley production is used as animal feed, while 30% is used as a source of fermentable material for beer, or further distilled into whisky, and as a component of various foods. It is used in soups and stews, and in barley bread of various cultures. Barley grains are commonly made into malt in a traditional and ancient method of preparation. In English folklore, John Barleycorn personifies the grain, and the alcoholic beverages made from it. English pub names such as The Barley Mow allude to barley's role in the production of beer.

Etymology

The Old English word for barley was bere.[4] This survives in the north of Scotland as bere; it is used for a strain of six-row barley grown there.[5] Modern English barley derives from the Old English adjective bærlic, meaning "of barley".[3][6] The word barn derives from Old English bere-aern meaning "barley-store".[3] The name of the genus is from Latin hordeum, barley, likely related to Latin horrere, to bristle.[7]

Description

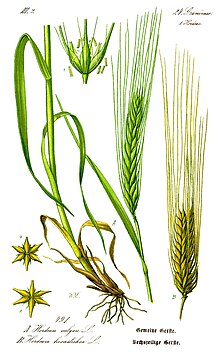

Barley is a cereal, a member of the grass family with edible grains. Its flowers are clusters of spikelets arranged in a distinctive herringbone pattern. Each spikelet has a long thin awn (to 160 mm (6.3 in) long), making the ears look tufted. The spikelets are in clusters of three. In six-row barley, all three spikelets in each cluster are fertile; in two-row barley, only the central one is fertile.[8] It is a self-pollinating, diploid species with 14 chromosomes.[9]

The genome of barley was sequenced in 2012 by the International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium and the UK Barley Sequencing Consortium.[10] The genome is organised into seven pairs[11] of nuclear chromosomes (recommended designations: 1H, 2H, 3H, 4H, 5H, 6H and 7H), and one mitochondrial and one chloroplast chromosome, with a total of 5000 Mbp.[12] Details of the genome are freely available in several barley databases.[13]

Origin

External phylogeny

The barley genus Hordeum is relatively closely related to wheat and rye within the Triticeae, and more distantly to rice within the BOP clade of grasses (Poaceae).[14] The phylogeny of the Triticeae is complicated by horizontal gene transfer between species, so there is a network of relationships rather than a simple inheritance-based tree.[15]

| (Part of Poaceae) | |

Domestication

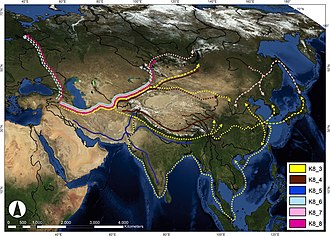

Barley was one of the first grains to be domesticated in the Fertile Crescent, an area of relatively abundant water in Western Asia,[17] around 9,000 BC.[16][18] Wild barley (H. vulgare ssp. spontaneum) ranges from North Africa and Crete in the west to Tibet in the east.[9] A study of genome-wide diversity markers found Tibet to be an additional center of domestication of cultivated barley.[19] The earliest archaeological evidence of the consumption of wild barley, Hordeum spontaneum, comes from the Epipaleolithic at Ohalo II at the southern end of the Sea of Galilee, where grinding stones with traces of starch were found. The remains were dated to about 23,000 BC.[9][20][21] The earliest evidence for the domestication of barley, in the form of cultivars that cannot reproduce without human assistance, comes from Mesopotamia, specifically the Jarmo region of modern-day Iraq, around 9,000-7,000 BC.[22][23]

Domestication changed the morphology of the barley grain substantially, from an elongated shape to a more rounded spherical one.[24] Wild barley has distinctive genes, alleles, and regulators with potential for resistance to abiotic or biotic stresses; these may help cultivated barley to adapt to climatic changes.[25] Wild barley has a brittle spike; upon maturity, the spikelets separate, facilitating seed dispersal. Domesticated barley has nonshattering spikelets, making it much easier to harvest the mature ears.[9] The nonshattering condition is caused by a mutation in one of two tightly linked genes known as Bt1 and Bt2; many cultivars possess both mutations. The nonshattering condition is recessive, so varieties of barley that exhibit this condition are homozygous for the mutant allele.[9] Domestication in barley is followed by the change of key phenotypic traits at the genetic level.[26]

The wild barley found currently in the Fertile Crescent may not be the progenitor of the barley cultivated in Eritrea and Ethiopia, indicating that it may have been domesticated separately in eastern Africa.[27]

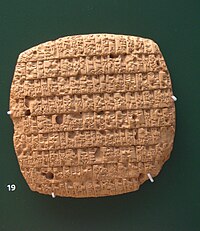

Spread

Archaeobotanical evidence shows that barley had spread throughout Eurasia by 2,000 BC.[16] Genetic analysis demonstrates that cultivated barley followed several different routes over time.[16] By 4200 BC domesticated barley had reached Eastern Finland.[28] Barley has been grown in the Korean Peninsula since the Early Mumun Pottery Period (circa 1500–850 BC).[29] Barley (Yava in Sanskrit) is mentioned many times in the Rigveda and other Indian scriptures as a principal grain in ancient India.[30] Traces of barley cultivation have been found in post-Neolithic Bronze Age Harappan civilization 5,700–3,300 years ago.[31] Barley beer was probably one of the first alcoholic drinks developed by Neolithic humans;[32] later it was used as currency.[32] The Sumerian language had a word for barley, akiti. In ancient Mesopotamia, a stalk of barley was the primary symbol of the goddess Shala.[33]

| jt barley determinative/ideogram |

| ||||

| jt (common) spelling |

| ||||

| šma determinative/ideogram |

|

Rations of barley for workers appear in Linear B tablets in Mycenaean contexts at Knossos and at Mycenaean Pylos.[34] In mainland Greece, the ritual significance of barley possibly dates back to the earliest stages of the Eleusinian Mysteries. The preparatory kykeon or mixed drink of the initiates, prepared from barley and herbs, mentioned in the Homeric hymn to Demeter. The goddess's name may have meant "barley-mother", incorporating the ancient Cretan word δηαί (dēai), "barley".[35][36] The practice was to dry the barley groats and roast them before preparing the porridge, according to Pliny the Elder's Natural History.[37] Tibetan barley has been a staple food in Tibetan cuisine since the fifth century AD. This grain, along with a cool climate that permitted storage, produced a civilization that was able to raise great armies.[38] It is made into a flour product called tsampa that is still a staple in Tibet.[39] In medieval Europe, bread made from barley and rye was peasant food, while wheat products were consumed by the upper classes.[40]

Taxonomy and varieties

Two-row and six-row barley

Spikelets are arranged in triplets which alternate along the rachis. In wild barley (and other Old World species of Hordeum), only the central spikelet is fertile, while the other two are reduced. This condition is retained in certain cultivars known as two-row barleys. A pair of mutations (one dominant, the other recessive) result in fertile lateral spikelets to produce six-row barleys.[9] A mutation in one gene, vrs1, is responsible for the transition from two-row to six-row barley.[41]

In traditional taxonomy, different forms of barley were classified as different species based on morphological differences. Two-row barley with shattering spikes (wild barley) was named Hordeum spontaneum (K. Koch). Two-row barley with nonshattering spikes was named as H. distichon (L.), six-row barley with nonshattering spikes as H. vulgare L. (or H. hexastichum L.), and six-row with shattering spikes as H. agriocrithon Åberg. Because these differences were driven by single-gene mutations, coupled with cytological and molecular evidence, most recent classifications treat these forms as a single species, H. vulgare L.[9]

-

6-row barley has three fertile spikelets per cluster

-

Two-row and six-row

Hulless barley

Hulless or "naked" barley (Hordeum vulgare L. var. nudum Hook. f.) is a form of domesticated barley with an easier-to-remove hull. Naked barley is an ancient food crop, but a new industry has developed around uses of selected hulless barley to increase the digestibility of the grain, especially for pigs and poultry.[42] Hulless barley has been investigated for several potential new applications as whole grain, bran, and flour.[43]

| Barley production – 2022 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Millions of tonnes |

| 23.4 | |

| 14.4 | |

| 11.3 | |

| 11.2 | |

| 10.0 | |

| 8.5 | |

| 7.4 | |

| 7.0 | |

| World | 154.9[44] |

Production

In 2022, world production of barley was 155 million tonnes, led by Russia accounting for 15% of the world total (table). France, Germany, and Canada were secondary producers. Worldwide barley production was fourth among grains, following maize (1.2 billion tonnes), wheat (808 million tonnes), and rice (776 million tonnes).[45]

Cultivation

Barley is a crop that prefers relatively low temperatures, 15 to 20 °C (59 to 68 °F) in the growing season; it is grown around the world in temperate areas. It grows best in well-drained soil in full sunshine. In the tropics and subtropics, it is grown for food and straw in South Asia, North and East Africa, and in the Andes of South America. In dry regions it requires irrigation.[46] It has a short growing season and is relatively drought-tolerant.[40] Barley is more tolerant of soil salinity than other cereals, varying in different cultivars.[47] It has less winter-hardiness than winter wheat and far less than rye.[48]

Like other cereals, barley is typically planted on tilled land. Seed was traditionally scattered, but in developed countries is usually drilled. As it grows it requires soil nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium), often supplied as fertilizers. It needs to be monitored for pests and diseases, and if necessary treated before these become serious. The stems and ears turn yellow when ripe, and the ears begin to droop. Traditional harvesting was by hand with sickles or scythes; in developed countries, harvesting is mechanised with combine harvesters.[46]

-

Young winter barley in early November,

Scotland, 2009 -

Spraying barley for rust fungus,

New Zealand, 1979 -

Harvesting winter barley with a combine harvester, Germany, 2017

Pests and diseases

Among the insect pests of barley are aphids such as Russian wheat aphid, caterpillars such as of the armyworm moth, barley mealybug, and wireworm larvae of click beetle genera such as Aeolus. Aphid damage can often be tolerated, whereas armyworms can eat whole leaves. Wireworms kill seedlings, and require seed or preplanting treatment.[46]

Serious fungal diseases of barley include powdery mildew caused by Blumeria graminis, leaf scald caused by Rhynchosporium secalis, barley rust caused by Puccinia hordei, crown rust caused by Puccinia coronata, various diseases caused by Cochliobolus sativus, Fusarium ear blight,[49] and stem rust (Puccinia graminis).[50] Bacterial diseases of barley include bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas campestris pv. translucens.[51] Barley is susceptible to several viral diseases, such as barley mild mosaic bymovirus.[52][53] Some viruses, such as barley yellow dwarf virus, vectored by the rice root aphid, can cause serious crop injury.[54]

For durable disease resistance, quantitative resistance is more important than qualitative resistance. The most important foliar diseases have corresponding resistance gene regions on all chromosomes of barley.[11] A large number of molecular markers are available for breeding of resistance to leaf rust, powdery mildew, Rhynchosporium secalis, Pyrenophora teres f. teres, Barley yellow dwarf virus, and the Barley yellow mosaic virus complex.[55][56]

-

Wireworms, the larvae of click beetles, kill barley seedlings.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Barley

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk