A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| History of Russia |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of the Soviet Union between 1927 and 1953 covers the period in Soviet history from the establishment of Stalinism through victory in the Second World War and down to the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. Stalin sought to destroy his enemies while transforming Soviet society with central planning, in particular through the forced collectivization of agriculture and rapid development of heavy industry. Stalin consolidated his power within the party and the state and fostered an extensive cult of personality. Soviet secret-police and the mass-mobilization of the Communist Party served as Stalin's major tools in molding Soviet society. Stalin's methods in achieving his goals, which included party purges, ethnic cleansings, political repression of the general population, and forced collectivization, led to millions of deaths: in Gulag labor camps[1] and during famine.[2][3]

World War II, known as "the Great Patriotic War" by Soviet historians, devastated much of the USSR, with about one out of every three World War II deaths representing a citizen of the Soviet Union. In the course of World War II, the Soviet Union's armies occupied Eastern Europe, where they established or supported Communist puppet governments. By 1949, the Cold War had started between the Western Bloc and the Eastern (Soviet) Bloc, with the Warsaw Pact (created 1955) pitched against NATO (created 1949) in Europe. After 1945, Stalin did not directly engage in any wars, continuing his totalitarian rule until his death in 1953.[4]

Soviet state's development

Industrialization in practice

The mobilization of resources by state planning expanded the country's industrial base. From 1928 to 1932, pig iron output, necessary for further development of the industrial infrastructure rose from 3.3 million to 6.2 million tons per year. Coal production, a basic fuel of modern economies and Stalinist industrialization, rose from 35.4 million to 64 million tons, and the output of iron ore rose from 5.7 million to 19 million tons. A number of industrial complexes such as Magnitogorsk and Kuznetsk, the Moscow and Gorky automobile plants, the Ural Mountains and Kramatorsk heavy machinery plants, and Kharkiv, Stalingrad and Chelyabinsk tractor plants had been built or were under construction.[5]

In real terms, the workers' standards of living tended to drop, rather than rise during industrialization. Stalin's laws to "tighten work discipline" made the situation worse: e.g., a 1932 change to the RSFSR labor law code enabled firing workers who had been absent without a reason from the workplace for just one day. Being fired accordingly meant losing "the right to use ration and commodity cards" as well as the "loss of the right to use an apartment″ and even blacklisted for new employment which altogether meant a threat of starving.[6] Those measures, however, were not fully enforced, as managers were hard-pressed to replace these workers. In contrast, the 1938 legislation, which introduced labor books, followed by major revisions of the labor law, was enforced. For example, being absent or even 20 minutes late were grounds for becoming fired; managers who failed to enforce these laws faced criminal prosecution. Later, the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, 26 June 1940 "On the Transfer to the Eight-Hour Working Day, the Seven-day Work Week, and on the Prohibition of Unauthorized Departure by Laborers and Office Workers from Factories and Offices"[7] replaced the 1938 revisions with obligatory criminal penalties for quitting a job (2–4 months imprisonment), for being late 20 minutes (6 months of probation and pay confiscation of 25 per cent), etc.

Based on these figures, the Soviet government declared that the Five Year Industrial Production Plan had been fulfilled by 93.7% in only four years, while parts devoted to the heavy industry parts were fulfilled by 108%. Stalin in December 1932 declared the plan success to the Central Committee since increases in the output of coal and iron would fuel future development.[8]

During the Second Five-Year Plan (1933–1937), on the basis of the huge investment during the first plan, the industry expanded extremely rapidly and nearly reached the plan's targets. By 1937, coal output was 127 million tons, pig iron 14.5 million tons, and there had been very rapid development of the armaments industry.[9]

While making a massive leap in industrial capacity, the First Five Year Plan was extremely harsh on industrial workers; quotas were difficult to fulfill, requiring that miners put in 16- to 18-hour workdays.[10] Failure to fulfill quotas could result in treason charges.[11] Working conditions were poor, even hazardous. Due to the allocation of resources for the industry along with decreasing productivity since collectivization, a famine occurred. In the construction of the industrial complexes, inmates of Gulag camps were used as expendable resources. But conditions improved rapidly during the second plan. Throughout the 1930s, industrialization was combined with a rapid expansion of technical and engineering education as well as increasing emphasis on munitions.[12]

From 1921 until 1954, the police state operated at high intensity, seeking out anyone accused of sabotaging the system. The estimated numbers vary greatly. Perhaps, 3.7 million people were sentenced for alleged counter-revolutionary crimes, including 600,000 sentenced to death, 2.4 million sentenced to labor camps, and 700,000 sentenced to expatriation. Stalinist repression reached its peak during the Great Purge of 1937–1938, which removed many skilled managers and experts and considerably slowed industrial production in 1937.[13]

Economy

Collectivization of agriculture

Under the NEP (New Economic Policy), Lenin had to tolerate the continued existence of privately owned agriculture. He decided to wait at least 20 years before attempting to place it under state control and in the meantime concentrate on industrial development. However, after Stalin's rise to power, the timetable for collectivization was shortened to just five years. Demand for food intensified, especially in the USSR's primary grain producing regions, with new, forced approaches implemented. Upon joining kolkhozes (collective farms), peasants had to give up their private plots of land and property. Every harvest, Kolkhoz production was sold to the state for a low price set by the state itself. However, the natural progress of collectivization was slow, and the November 1929 Plenum of the Central Committee decided to accelerate collectivization through force. In any case, Russian peasant culture formed a bulwark of traditionalism that stood in the way of the Soviet state's goals.

Given the goals of the first Five Year Plan, the state sought increased political control of agriculture in order to feed the rapidly growing urban population and to obtain a source of foreign currency through increased cereal exports. Given its late start, the USSR needed to import a substantial number of the expensive technologies necessary for heavy industrialization.

By 1936, about 90% of Soviet agriculture had been collectivized. In many cases, peasants bitterly opposed this process and often slaughtered their animals rather than give them to collective farms, even though the government only wanted the grain. Kulaks, prosperous peasants, were forcibly resettled to Kazakhstan, Siberia and the Russian Far North (a large portion of the kulaks served at forced labor camps). However, just about anyone opposing collectivization was deemed a "kulak". The policy of liquidation of kulaks as a class—formulated by Stalin at the end of 1929—meant some executions, and even more deportation to special settlements and, sometimes, to forced labor camps.[14]

Despite the expectations, collectivization led to a catastrophic drop in farm productivity, which did not return to the levels achieved under the NEP until 1940. The upheaval associated with collectivization was particularly severe in Ukraine and the heavily Ukrainian Volga region. Peasants slaughtered their livestock en masse rather than give them up. In 1930 alone, 25% of the nation's cattle, sheep, and goats, and one-third of all pigs were killed. It was not until the 1980s that the Soviet livestock numbers would return to their 1928 level. Government bureaucrats, who had been given a rudimentary education on farming techniques, were dispatched to the countryside to "teach" peasants the new ways of socialist agriculture, relying largely on theoretical ideas that had little basis in reality.[15] Even after the state inevitably won and succeeded in imposing collectivization, the peasants did everything they could in the way of sabotage. They cultivated far smaller portions of their land and worked much less. The scale of the Ukrainian famine has led many Ukrainian scholars to argue that there was a deliberate policy of genocide against the Ukrainian people. Other scholars argue that the massive death totals were an inevitable result of a very poorly planned operation against all peasants, who had given little support to Lenin or Stalin.

Almost 99% of all cultivated land had been pulled into collective farms by the end of 1937. The ghastly price paid by the peasantry has yet to be established with precision, but probably up to 5 million people died of persecution or starvation in these years. Ukrainians and Kazakhs suffered worse than most nations.

— Robert Service, Comrades! A History of World Communism (2007) p. 145

In Ukraine alone, the number of people who died in the famines is now estimated to be 3.5 million.[16][17]

The USSR took over Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in 1940, which were lost to Germany in 1941, and then recovered in 1944. The collectivization of their farms began in 1948. Using terror, mass killings and deportations, most of the peasantry was collectivized by 1952. Agricultural production fell dramatically in all the other Soviet Republics.[18]

Rapid industrialization

In the period of rapid industrialization and mass collectivization preceding World War II, Soviet employment figures experienced exponential growth. 3.9 million jobs per annum were expected by 1923, but the number actually climbed to an astounding 6.4 million. By 1937, the number rose yet again, to about 7.9 million. Finally, in 1940 it reached 8.3 million. Between 1926 and 1930, the urban population increased by 30 million. Unemployment had been a problem in late Imperial Russia and even under the NEP, but it ceased being a major factor after the implementation of Stalin's massive industrialization program. The sharp mobilization of resources used in order to industrialize the heretofore agrarian society created a massive need for labor; unemployment virtually dropped to zero. Wage setting by Soviet planners also contributed to the sharp decrease in unemployment, which dropped in real terms by 50% from 1928 to 1940. With wages artificially depressed, the state could afford to employ far more workers than would be financially viable in a market economy. Several ambitious extraction projects were begun that endeavored to supply raw materials for both military hardware and consumer goods.

The Moscow and Gorky automobile plants produced automobiles for the public—despite few Soviet citizens being able to afford a car—and the expansion of steel production and other industrial materials made the manufacture of a greater number of cars possible. Car and truck production, for example, reached 200,000 in 1931.[19]

A minimum wage of 110–115 rubles was established in 1937; private gardens were allowed for one million workers to farm in their private plots. Even so, most Soviet workers lived in crowded communal housings and dormitories and suffered from extreme poverty.[20]

Society

Propaganda

Most of the top communist leaders in the 1920s and 1930s had been propagandists or editors before 1917, and were keenly aware of the importance of propaganda. As soon as they gained power in 1917 they seized the monopoly of all communication media, and greatly expanded their propaganda apparatus in terms of newspapers, magazines and pamphlets. Radio became a powerful tool in the 1930s.[21] Stalin, for example, has been an editor of Pravda. Besides the national newspapers Pravda and Izvestia, there were numerous regional publications as well as newspapers and magazines and all the important languages. Ironclad uniformity of opinion was the norm during the Soviet era. Typewriters and printing presses were closely controlled until the late 1980s to prevent unauthorized publications. Samizdat illegal circulation of subversive fiction and nonfiction was brutally suppressed. The rare exceptions to 100% uniformity in the official media were indicators of high-level battles. The Soviet draft constitution of 1936 was an instance. Pravda and Trud (the paper for manual workers) praised the draft constitution. However Izvestiia was controlled by Nikolai Bukharin and it published negative letters and reports. Bukharin won out and the party line changed and started to attack "Trotskyite" oppositionists and traitors. Bukharin's success was short-lived; he was arrested in 1937, given a show trial and executed.[22]

Education

Industrial workers needed to be educated in order to be competitive and so embarked on a program contemporaneous with industrialization to greatly increase the number of schools and the general quality of education. In 1927, 7.9 million students attended 118,558 schools. By 1933, the number rose to 9.7 million students in 166,275 schools. In addition, 900 specialist departments and 566 institutions were built and fully operational by 1933. Literacy rates increased substantially as a result, especially in the Central Asian republics.[23][24]

Women

The Soviet people also benefited from a type of social liberalization. Women were to be given the same education as men and, at least legally speaking, obtained the same rights as men in the workplace.[citation needed] Although in practice these goals were not reached, the efforts to achieve them and the statement of theoretical equality led to a general improvement in the socio-economic status of women.[citation needed]

Women were notably recruited as clerks for the expanding department stores, resulting in a "feminization" of department stores as the number of female sales staff rose from 45 percent of the total sales staff in 1935 to 62 percent of the total sales staff in 1938.[25] This was in part due to a propaganda campaign launched in 1931 which linked femininity with "culture" and asserted that the New Soviet Woman was also a working woman.[25] Furthermore, department store staff had a low status in the Soviet Union and many men did not want to work as sales staff, leading to the jobs as sales staff going to poorly educated working-class women and from women newly arrived in the cities from the countryside.[25]

However, many rights were rolled back by the authorities during this era, such as abortion, which was legalized before Stalin came to power, was banned in 1936[26] after controversial debate among citizens.[27] Women's issues were also largely ignored by the government.[28]

Health

Stalinist development also contributed to advances in health care, which marked a massive improvement over the Imperial era. Stalin's policies granted the Soviet people access to free health care and education. Widespread immunization programs created the first generation free from the fear of typhus and cholera. The occurrences of these diseases dropped to record-low numbers and infant mortality rates were substantially reduced, resulting in the life expectancy for both men and women to increase by over 20 years by the mid-to-late 1950s.[29]

Youth

The Komsomol or Youth Communist League, was an entirely new youth organization designed by Lenin became an enthusiastic strike force that organized communism across the Soviet Union often called on to attack traditional enemies.[30] The Komsomol played an important role as a mechanism for teaching Party values to the younger generation. The Komsomol also served as a mobile pool of labor and political activism, with the ability to relocate to areas of high-priority at short notice. In the 1920s the Kremlin assigned Komsomol major responsibilities for promoting industrialization at the factory level. In 1929 7,000 Komsomol cadets were building the tractor factory in Stalingrad, 56,000 others built factories in the Urals, and 36,000 were assigned work underground in the coal mines. The goal was to provide an energetic hard-core of Bolshevik activists to influence their coworkers the factories and mines that were at the center of communist ideology.[31][32]

Komsomol adopted meritocratic, supposedly class-blind membership policies in 1935, but the result was a decline in working class youth members, and a dominance by the better educated youth. A new social hierarchy emerged as young professionals and students joined the Soviet elite, displacing proletarians. Komsomol's membership policies in the 1930s reflected the broader nature of Stalinism, combining Leninist rhetoric about class-free progress with Stalinist pragmatism focused on getting the most enthusiastic and skilled membership.[33] Under Stalin, the death penalty was also extended to adolescents as young as 12 years old in 1935.[34][35][36]

Modernity

Urban women under Stalin, paralleling the modernization of western countries, were also the first generation of women able to give birth in a hospital with access to prenatal care. Education was another area in which there was improvement after economic development, also paralleling other western countries. The generation born during Stalin's rule was the first near-universally literate generation. Some engineers were sent abroad to learn industrial technology, and hundreds of foreign engineers were brought to Russia on contract. Transport links were also improved, as many new railways were built, although with forced labour, costing thousands of lives. Workers who exceeded their quotas, Stakhanovites, received many incentives for their work, although many such workers were in fact "arranged" to succeed by receiving extreme help in their work, and then their achievements were used for propaganda.[37]

Religion

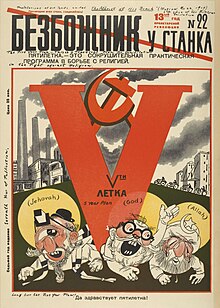

The systematic attacks on the Russian Orthodox Church began as soon as the Bolsheviks took power in 1917. In the 1930s, Stalin intensified his war on organized religion.[38] Nearly all churches and monasteries were closed and tens of thousands of clergymen were imprisoned or executed. Historian Dimitry Pospielovski has estimated that between 5,000 and 10,000 Orthodox clergy died by execution or in prison 1918–1929, plus an additional 45,000 in 1930–1939. Monks, nuns, and related personnel added an additional 40,000 dead.[39]

The state propaganda machine vigorously promoted atheism and denounced religion as being an artifact of capitalist society. In 1937, Pope Pius XI decried the attacks on religion in the Soviet Union. By 1940, only a small number of churches remained open. The early anti-religious campaigns under Lenin were mostly directed at the Russian Orthodox Church, as it was a symbol of the czarist government. In the 1930s however, all faiths were targeted: minority Christian denominations, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism. During World War II state authorities eased pressures on Religion in Russia and stopped prosecuting the church. The Orthodox Church was, therefore, able to help the Soviet Army to defend Russia.[40] Religions in former USSR republics revived and once again flourished after the fall of communism in the 1990s. As Paul Froese explains:

- Atheists waged a 70-year war on religious belief in the Soviet Union. The Communist Party destroyed churches, mosques, and temples; it executed religious leaders; it flooded the schools and media with anti-religious propaganda; and it introduced a belief system called “scientific atheism,” complete with atheist rituals, proselytizers, and a promise of worldly salvation. But in the end, a majority of older Soviet citizens retained their religious beliefs and a crop of citizens too young to have experienced pre-Soviet times acquired religious beliefs.[41]

According to 2012 official statistics, nearly 15% of ethnic Russians identify as atheist, and nearly 27% identify as unaffiliated.[42]

Ethnic policies

The Soviet Union authorities systematically promoted the national consciousness of indigenous peoples and established institutional forms characteristic of a modern nation for them.[43] In Central Asia the liberation of women was approached in the same revolutionary way as the assault on the religion. In 1927 the campaign against paranja (veil) started, called "hujum" (assault). However, it produced a massive backlash and paranja did not disappear until the 1950s.[44][45]

In 1937, as a part of the Great Purge, repressive “national operations” were conducted. Representatives of “Western” minorities were targeted because of their possible connections to countries hostile to the USSR and fear of disloyalty in case of an invasion.[46]

Great Purge

As this process unfolded, Stalin consolidated near-absolute power by destroying the potential opposition. In 1936–1938, about three quarters of a million Soviets were executed, and more than a million others were sentenced to lengthy terms in harsh labour camps. Stalin's Great Terror ravaged the ranks of factory directors and engineers, and removed most of the senior officers in the Army.[47] The pretext was the 1934 assassination of Sergei Kirov (which many suspect Stalin of having planned, although there is no evidence for this).[48] Nearly all the old pre-1918 Bolsheviks were purged. Trotsky was expelled from the party in 1927, exiled to Kazakhstan in 1928, expelled from the USSR in 1929, and assassinated in 1940. Stalin used the purges to politically and physically destroy his other formal rivals (and former allies) accusing Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev of being behind Kirov's assassination and planning to overthrow Stalin. Ultimately, the people arrested were tortured and forced to confess to being spies and saboteurs, and quickly convicted and executed.[49]

Several show trials were held in Moscow, to serve as examples for the trials that local courts were expected to carry out elsewhere in the country. There were four key trials from 1936 to 1938, The Trial of the Sixteen was the first (December 1936); then the Trial of the Seventeen (January 1937); then the trial of Red Army generals, including Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky (June 1937); and finally the Trial of the Twenty One (including Bukharin) in March 1938. During these, the defendants typically confessed to sabotage, spying, counter-revolution, and conspiring with Germany and Japan to invade and partition the Soviet Union. The initial trials in 1935–1936 were carried out by the OGPU under Genrikh Yagoda. In turn the prosecutors were tried and executed. The secret police were renamed the NKVD and control given to Nikolai Yezhov, known as the "Bloody Dwarf".[50]

The "Great Purge" swept the Soviet Union in 1937. It was widely known as the "Yezhovschina", the "Reign of Yezhov". The rate of arrests was staggering. In the armed forces alone, 34,000 officers were purged including many at the higher ranks.[51] The entire Politburo and most of the Central Committee were purged, along with foreign communists who were living in the Soviet Union, and numerous intellectuals, bureaucrats, and factory managers. The total of people imprisoned or executed during the Yezhovschina numbered about two million.[52] By 1938, the mass purges were starting to disrupt the country's infrastructure, and Stalin began winding them down. Yezhov was gradually relieved of power. Yezhov was relieved of all powers in 1939, then tried and executed in 1940. His successor as head of the NKVD (from 1938 to 1945) was Lavrentiy Beria, a Georgian friend of Stalin's. Arrests and executions continued into 1952, although nothing on the scale of the Yezhovschina ever happened again.

During this period, the practice of mass arrest, torture, and imprisonment or execution without trial, of anyone suspected by the secret police of opposing Stalin's regime became commonplace. By the NKVD's own count, 681,692 people were shot during 1937–1938 alone, and hundreds of thousands of political prisoners were transported to Gulag work camps.[53] The mass terror and purges were little known to the outside world, and some western intellectuals and fellow travellers continued to believe that the Soviets had created a successful alternative to a capitalist world. In 1936, the country adopted its first formal constitution, which only on paper granted freedom of speech, religion, and assembly. Scholars estimate the total death toll for the Great Purge (1936–1938), including fatalities attributed to prison conditions, to be roughly 700,000-1.2 million.[54][55][56][57][58]

In March 1939, the 18th congress of the Communist Party was held in Moscow. Most of the delegates present at the 17th congress in 1934 were gone, and Stalin was heavily praised by Litvinov and the western democracies criticized for failing to adopt the principles of "collective security" against Nazi Germany.

Interpreting the purges

Two major lines of interpretation have emerged among historians. One argues that the purges reflected Stalin's ambitions, his paranoia, and his inner drive to increase his power and eliminate potential rivals. Revisionist historians explain the purges by theorizing that rival factions exploited Stalin's paranoia and used terror to enhance their own position. Peter Whitewood examines the first purge, directed at the Army, and comes up with a third interpretation that: Stalin and other top leaders, assuming that they were always surrounded by enemies, always worried about the vulnerability and loyalty of the Red Army. It was not a ploy – Stalin truly believed it. “Stalin attacked the Red Army because he seriously misperceived a serious security threat”; thus “Stalin seems to have genuinely believed that foreign‐backed enemies had infiltrated the ranks and managed to organize a conspiracy at the very heart of the Red Army.” The purge hit deeply from June 1937 and November 1938, removing 35,000; many were executed. Experience in carrying out the purge facilitated purging other key elements in the wider Soviet polity.[59][60] Historians often cite the disruption as factors in its disastrous military performance during the German invasion.[61]

Foreign relations, 1927–1939

The Soviet government had forfeited foreign-owned private companies during the creation of the RSFSR and the USSR. Foreign investors did not receive any monetary or material compensation. The USSR also refused to pay tsarist-era debts to foreign debtors. The young Soviet polity was a pariah because of its openly stated goal of supporting the overthrow of capitalistic governments. It sponsored workers' revolts to overthrow numerous capitalistic European states, but they all failed. Lenin reversed radical experiments and restored a sort of capitalism with the NEC. The Comintern was ordered to stop organizing revolts. Starting in 1921 Lenin sought trade, loans and recognition. One by one, foreign states reopened trade lines and recognized the Soviet government. The United States was the last major polity to recognise the USSR in 1933. In 1934, the French government proposed an alliance and led 30 governments to invite the USSR to join the League of Nations. The USSR had achieved legitimacy but was expelled in December 1939 for aggression against Finland.[62][63]

In 1928, Stalin pushed a leftist policy based on his belief in an imminent great crisis for capitalism. Various European communist parties were ordered not to form coalitions and instead to denounce moderate socialists as social fascists. Activists were sent into labour unions to take control away from socialists–a move the British unions never forgave. By 1930, the Stalinists started suggesting the value of alliance with other parties, and by 1934 the idea to form a Popular Front had emerged. Comintern agent Willi Münzenberg was especially effective in organizing intellectuals, antiwar and pacifist elements to join the anti-Nazi coalition.[64] Communists would form coalitions with any party to fight fascism. For Stalinists, the Popular Front was simply an expedient, but to rightists, it represented the desirable form of transition to socialism.[65]

Franco-Soviet relations were initially hostile because the USSR officially opposed the World War I peace settlement of 1919 that France emphatically championed. While the Soviet Union was interested in conquering territories in Eastern Europe, France was determined to protect the fledgling states there. However, Adolf Hitler's foreign policy centered on a massive seizure of Central European, Eastern European, and Russian lands for Germany's own ends, and when Hitler pulled out of the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva in 1933, the threat hit home. Soviet Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov reversed Soviet policy regarding the Paris Peace Settlement, leading to a Franco-Soviet rapprochement. In May 1935, the USSR concluded pacts of mutual assistance with France and Czechoslovakia. Stalin-ordered the Comintern to form a popular front with leftist and centrist parties against the forces of Fascism. The pact was undermined, however, by strong ideological hostility to the Soviet Union and the Comintern's new front in France, Poland's refusal to permit the Red Army on its soil, France's defensive military strategy, and a continuing Soviet interest in patching up relations with Nazi Germany.

The Soviet Union supplied military aid to the Republican faction in the Second Spanish Republic, including munitions and soldiers, and helped far-left activists come to Spain as volunteers. The Spanish government let the USSR have the government treasury. Soviet units systematically liquidated anarchist supporters of the Spanish government. Moscow's support of the government gave the Republicans a Communist taint in the eyes of anti-Bolsheviks in Britain and France, weakening the calls for Anglo-French intervention in the war.[66]

Nazi Germany promulgated an Anti-Comintern Pact with Imperialist Japan and Fascist Italy, along with various Central and Eastern European states (such as Hungary), ostensibly to suppress Communist activity but more realistically to forge an alliance against the USSR.[67]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Stalinist_eraText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk