A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (December 2019) |

Creativity is a characteristic of someone (or some process) that forms something novel and valuable. The created item may be intangible (such as an idea, a scientific theory, a musical composition, or a joke) or a physical object (such as an invention, a printed literary work, or a painting). Creativity enables people to solve problems in new or innovative ways.

Scholarly interest in creativity is found in a number of disciplines, primarily psychology, business studies, and cognitive science. However, it is also present in education, the humanities (including philosophy and the arts), theology, and the social sciences (such as sociology, linguistics, and economics), as well as engineering, technology, and mathematics. These disciplines cover the relations between creativity and general intelligence, personality type, mental and neural processes, mental health, and artificial intelligence; the potential for fostering creativity through education, training, leadership, and organizational practices;[1] the factors that determine how creativity is evaluated and perceived;[2] the application of creative resources to improve the effectiveness of teaching and learning; and the fostering of creativity for national economic benefit. According to Harvard Business School,[3] it benefits business by encouraging innovation, boosting productivity, enabling adaptability, and fostering growth.

Etymology

The English word "creativity" comes from the Latin terms creare (meaning 'to create') and facere (meaning 'to make'). Its derivational suffixes also come from Latin. The word "create" appeared in English as early as the 14th century—notably in Chaucer's The Parson's Tale[4] to indicate divine creation.[5]

The modern meaning of creativity in reference to human creation did not emerge until after the Enlightenment.

Definition

In a summary of scientific research into creativity, Michael Mumford suggests, "We seem to have reached a general agreement that creativity involves the production of novel, useful products."[6] In Robert Sternberg's words, creativity produces "something original and worthwhile".[7]

Authors have diverged dramatically in their precise definitions beyond these general commonalities: Peter Meusburger estimates that over a hundred different definitions can be found in the literature, typically elaborating on the context (field, organization, environment, etc.) that determines the originality and/or appropriateness of the created object and the processes through which it came about.[8] As an illustration, one definition given by Dr. E. Paul Torrance in the context of assessing an individual's creative ability is "a process of becoming sensitive to problems, deficiencies, gaps in knowledge, missing elements, disharmonies, and so on; identifying the difficulty; searching for solutions, making guesses, or formulating hypotheses about the deficiencies: testing and retesting these hypotheses and possibly modifying and retesting them; and finally communicating the results."[9]

Ignacio L. Götz, following the etymology of the word, argues that creativity is not necessarily "making". He confines it to the act of creating without thinking about the end product.[10] While many definitions of creativity seem almost synonymous with originality, he also emphasized the difference between creativity and originality. Götz asserted that one can be creative without necessarily being original. When someone creates something, they are certainly creative at that point, but they may not be original in the case that their creation is not something new. However, originality and creativity can go hand-in-hand.[10]

Creativity in general is usually distinguished from innovation in particular, where the stress is on implementation. For example, Teresa Amabile and Pratt define creativity as the production of novel and useful ideas and innovation as the implementation of creative ideas,[11] while the OECD and Eurostat state that "Innovation is more than a new idea or an invention. An innovation requires implementation, either by being put into active use or by being made available for use by other parties, firms, individuals, or organizations."[12]

There is also emotional creativity,[13] which is described as a pattern of cognitive abilities and personality traits related to originality and appropriateness in emotional experience.[14]

Aspects

Theories of creativity (and empirical investigations of why some people are more creative than others) have focused on a variety of aspects. The dominant factors are usually identified as "the four P's", a framework first put forward by Mel Rhodes:[15]

- Process

- A focus on process is shown in cognitive approaches that try to describe thought mechanisms and techniques for creative thinking. Theories invoking divergent rather than convergent thinking (such as that of Guilford), or those describing the staging of the creative process (such as that of Wallas) are primarily theories of the creative process.

- Product

- A focus on a creative product usually attempts to assess creative output, whether for psychometrics (see below) or to understand why some objects are considered creative. It is from a consideration of product that the standard definition of creativity as the production of something novel and useful arises.[16]

- Person

- A focus on the nature of the creative person considers more general intellectual habits, such as openness, levels of ideation, autonomy, expertise, exploratory behavior, and so on.

- Press and place

- A focus on place (or press) considers the circumstances in which creativity flourishes, such as degrees of autonomy, access to resources, and the nature of gatekeepers. Creative lifestyles are characterized by nonconforming attitudes and behaviors, as well as flexibility.[17]

In 2013, based on a sociocultural critique of the Four P model as individualistic, static, and decontextualized, Vlad Petre Glăveanu proposed a "five A's" model consisting of actor, action, artifact, audience, and affordance.[18] In this model, the actor is the person with attributes but also located within social networks; action is the process of creativity not only in internal cognitive terms but also external, bridging the gap between ideation and implementation; artifacts emphasize how creative products typically represent cumulative innovations over time rather than abrupt discontinuities; and "press/place" is divided into audience and affordance, which consider the interdependence of the creative individual with the social and material world, respectively. Although not supplanting the four Ps model in creativity research, the five As model has exerted influence over the direction of some creativity research,[19] and has been credited with bringing coherence to studies across a number of creative domains.[20]

Conceptual history

Ancient

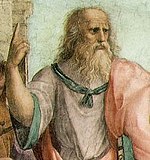

Most ancient cultures, including Ancient Greece,[21] Ancient China, and Ancient India,[22] lacked the concept of creativity, seeing art as a form of discovery and not creation. The ancient Greeks had no terms corresponding to "to create" or "creator" except for the expression "poiein" ("to make"), which only applied to poiesis (poetry) and to the poietes (poet, or "maker" who made it. Plato did not believe in art as a form of creation. Asked in The Republic,[23] "Will we say of a painter that he makes something?" he answers, "Certainly not, he merely imitates."[21]

It is commonly argued[by whom?] that the notion of "creativity" originated in Western cultures through Christianity, asa matter of[clarification needed] divine inspiration.[5] According to scholars, "the earliest Western conception of creativity was the Biblical story of the creation given in Genesis."[22]: 18 However, this is not creativity in the modern sense, which did not arise until the Renaissance. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, creativity was the sole province of God; humans were not considered to have the ability to create something new except as an expression of God's work.[24] A concept similar to that in Christianity existed in Greek culture. For instance, Muses were seen as mediating inspiration from the gods.[25] Romans and Greeks invoked the concept of an external creative "daemon" (Greek) or "genius" (Latin), linked to the sacred or the divine. However, none of these views are similar to the modern concept of creativity, and the rejection of creativity in favor of discovery and the belief that individual creation was a conduit of the divine would dominate the West probably until the Renaissance and even later.[24][22]: 18–19

Renaissance

It was during the Renaissance that creativity was first seen, not as a conduit for the divine, but from the abilities of "great men".[22]: 18–19 The development of the modern concept of creativity began in the Renaissance, when creation began to be perceived as having originated from the abilities of the individual and not God. This could be attributed to the leading intellectual movement of the time, aptly named humanism, which developed an intensely human-centric outlook on the world, valuing the intellect and achievement of the individual.[26] From this philosophy arose the Renaissance man (or polymath), an individual who embodies the principles of humanism in their ceaseless courtship with knowledge and creation.[27] One of the most well-known and immensely accomplished examples is Leonardo da Vinci.

Enlightenment and thereafter

However, the shift from divine inspiration to the abilities of the individual was gradual and would not become immediately apparent until the Enlightenment.[22]: 19–21 By the 18th century and the Age of Enlightenment, mention of creativity (notably in aesthetics), linked with the concept of imagination, became more frequent.[21] In the writing of Thomas Hobbes, imagination became a key element of human cognition;[5] William Duff was one of the first to identify imagination as a quality of genius, typifying the separation being made between talent (productive, but not new ground) and genius.[25]

As an independent topic of study, creativity effectively received no attention until the 19th century.[25] Runco and Albert argue that creativity as the subject of proper study began seriously to emerge in the late 19th century with the increased interest in individual differences inspired by the arrival of Darwinism. In particular, they refer to the work of Francis Galton, who, through his eugenicist outlook took a keen interest in the heritability of intelligence, with creativity taken as an aspect of genius.[5]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leading mathematicians and scientists such as Hermann von Helmholtz (1896)[28] and Henri Poincaré (1908)[29] began to reflect on and publicly discuss their creative processes.

Modern

The insights of Poincaré and von Helmholtz were built on in early accounts of the creative process by pioneering theorists such as Graham Wallas and Max Wertheimer. In his work Art of Thought, published in 1926,[30] Wallas presented one of the first models of the creative process. In the Wallas stage model, creative insights and illuminations may be explained by a process consisting of five stages:

- preparation (preparatory work on a problem that focuses the individual's mind on the problem and explores the problem's dimensions),

- incubation (in which the problem is internalized into the unconscious mind and nothing appears externally to be happening),

- intimation (the creative person gets a "feeling" that a solution is on its way),

- illumination or insight (in which the creative idea bursts forth from its preconscious processing into conscious awareness);

- verification (in which the idea is consciously verified, elaborated, and then applied).

Wallas' model is also often treated as four stages, with "intimation" seen as a sub-stage.

Wallas considered creativity to be a legacy of the evolutionary process, which allowed humans to quickly adapt to rapidly changing environments. Simonton[31] provides an updated perspective on this view in his book, Origins of Genius: Darwinian Perspectives on creativity.

In 1927, Alfred North Whitehead gave the Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh, later published as Process and Reality.[32] He is credited with having coined the term "creativity" to serve as the ultimate category of his metaphysical scheme: "Whitehead actually coined the term—our term, still the preferred currency of exchange among literature, science, and the arts—a term that quickly became so popular, so omnipresent, that its invention within living memory, and by Alfred North Whitehead of all people, quickly became occluded".[33]

Although psychometric studies of creativity had been conducted by The London School of Psychology as early as 1927 with the work of H.L. Hargreaves into the Faculty of Imagination,[34] the formal psychometric measurement of creativity, from the standpoint of orthodox psychological literature, is usually considered to have begun with J.P. Guilford's address to the American Psychological Association in 1950.[35] The address helped to popularize the study of creativity and to focus attention on scientific approaches to conceptualizing creativity. Statistical analyzes led to the recognition of creativity (as measured) as a separate aspect of human cognition from IQ-type intelligence, into which it had previously been subsumed. Guilford's work suggested that above a threshold level of IQ, the relationship between creativity and classically measured intelligence broke down.[36]

"Four C" model

James C. Kaufman and Ronald A. Beghetto introduced a "four C" model of creativity. The four "C's" are the following:

- mini-c ("transformative learning" involving "personally meaningful interpretations of experiences, actions, and insights").

- little-c (everyday problem-solving and creative expression).

- Pro-C (exhibited by people who are professionally or vocationally creative though not necessarily eminent).

- Big-C (creativity considered great in the given field).

This model was intended to help accommodate models and theories of creativity that stressed competence as an essential component and the historical transformation of a creative domain as the highest mark of creativity. It also, the authors argued, made a useful framework for analyzing creative processes in individuals.[37]

The contrast between the terms "Big C" and "Little C" has been widely used. Kozbelt, Beghetto, and Runco use a little-c/Big-C model to review major theories of creativity.[36] Margaret Boden distinguishes between h-creativity (historical) and p-creativity (personal).[38]

Ken Robinson[39] and Anna Craft[40] focused on creativity in a general population, particularly with respect to education. Craft makes a similar distinction between "high" and "little c" creativity[40] and cites Robinson as referring to "high" and "democratic" creativity. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi defined creativity in terms of individuals judged to have made significant creative, perhaps domain-changing contributions.[41] Simonton analyzed the career trajectories of eminent creative people in order to map patterns and predictors of creative productivity.[42]

Process theories

There has been much empirical study in psychology and cognitive science of the processes through which creativity occurs. Interpretation of the results of these studies has led to several possible explanations of the sources and methods of creativity.

Incubation

Incubation is a temporary break from creative problem solving that can result in insight.[43] Empirical research has investigated whether, as the concept of "incubation" in Wallas's model implies, a period of interruption or rest from a problem may aid creative problem-solving. Early work proposed that creative solutions to problems arise mysteriously from the unconscious mind while the conscious mind is occupied on other tasks.[44] This hypothesis is discussed in Csikszentmihalyi's five-phase model of the creative process which describes incubation as a time when your unconscious takes over. This was supposed to allow for unique connections to be made without our consciousness trying to make logical order out of the problem.[45]

Ward[46] lists various hypotheses that have been advanced to explain why incubation may aid creative problem-solving and notes how some empirical evidence is consistent with a different hypothesis: Incubation aids creative problems in that it enables "forgetting" of misleading clues. The absence of incubation may lead the problem solver to become fixated on inappropriate strategies of solving the problem.[47]

Convergent and divergent thinking

J. P. Guilford[48] drew a distinction between convergent and divergent production (commonly renamed convergent and divergent thinking). Convergent thinking involves aiming for a single, correct, or best solution to a problem (e.g., "How can we get a crewed rocket to land on the moon safely and within budget?"). Divergent thinking, on the other hand, involves the creative generation of multiple answers to an open-ended prompt (e.g., "How can a chair be used?").[49] Divergent thinking is sometimes used as a synonym for creativity in psychology literature or is considered the necessary precursor to creativity.[50] However, as Runco points out, there is a clear distinction between creative thinking and divergent thinking.[49] Creative thinking focuses on the production, combination, and assessment of ideas to formulate something new and unique, while divergent thinking focuses on the act of conceiving of a variety of ideas that are not necessarily new or unique. Other researchers have occasionally used the terms flexible thinking or fluid intelligence, which are also roughly similar to (but not synonymous with) creativity.[51] While convergent and divergent thinking differ greatly in terms of approach to problem solving, it is believed[by whom?] that both are employed to some degree when solving most real-world problems.[49]

Creative cognition approach

In 1992, Finke et al. proposed the "Geneplore" model, in which creativity takes place in two phases: a generative phase, where an individual constructs mental representations called "preinventive" structures, and an exploratory phase where those structures are used to come up with creative ideas.[52] Some evidence shows that when people use their imagination to develop new ideas, those ideas are structured in predictable ways by the properties of existing categories and concepts.[53] Weisberg argued, by contrast, that creativity involves ordinary cognitive processes yielding extraordinary results.[54]

The Explicit–Implicit Interaction (EII) theory

Helie and Sun[55] proposed a framework for understanding creativity in problem solving, namely the Explicit-Implicit Interaction (EII) theory of creativity. This theory attempts to provide a more unified explanation of relevant phenomena (in part by reinterpreting/integrating various fragmentary existing theories of incubation and insight).

The EII theory relies mainly on five basic principles:

- the co-existence of and the difference between explicit and implicit knowledge

- simultaneous involvement of implicit and explicit processes in most tasks

- redundant representation of explicit and implicit knowledge

- integration of the results of explicit and implicit processing

- iterative (and possibly bidirectional) processing

A computational implementation of the theory was developed based on the CLARION cognitive architecture and used to simulate relevant human data. This work is an initial step in the development of process-based theories of creativity encompassing incubation, insight, and various other related phenomena.

Conceptual blending

In The Act of Creation, Arthur Koestler introduced the concept of bisociation – that creativity arises as a result of the intersection of two quite different frames of reference.[56] In the 1990s, various approaches in cognitive science that dealt with metaphor, analogy, and structure mapping converged, and a new integrative approach to the study of creativity in science, art, and humor emerged under the label conceptual blending.

Honing theory

Honing theory, developed principally by psychologist Liane Gabora, posits that creativity arises due to the self-organizing, self-mending nature of a worldview. The creative process is a way in which the individual hones (and re-hones) an integrated worldview. Honing theory places emphasis not only on the externally visible creative outcome but also on the internal cognitive restructuring and repair of the worldview brought about by the creative process and production.[57] When one is faced with a creatively demanding task, there is an interaction between one's conception of the task and one's worldview. The conception of the task changes through interaction with the worldview, and the worldview changes through interaction with the task. This interaction is reiterated until the task is complete, at which point the task is conceived of differently and the worldview is subtly or drastically transformed, following the natural tendency of a worldview to attempt to resolve dissonance and seek internal consistency amongst its components, whether they be ideas, attitudes, or bits of knowledge. Dissonance in a person's worldview is, in some cases, generated by viewing their peers' creative outputs, and so people pursue their own creative endeavors to restructure their worldviews and reduce dissonance.[57] This shift in worldview and cognitive restructuring through creative acts has also been considered as a way to explain possible benefits of creativity on mental health.[57] The theory also addresses challenges not addressed by other theories of creativity, such as the factors guiding restructuring and the evolution of creative works. [58]

A central feature of honing theory is the notion of a potential state.[59] Honing theory posits that creative thought proceeds not by searching through and randomly "mutating" predefined possibilities but by drawing upon associations that exist due to overlap in the distributed neural cell assemblies that participate in the encoding of experiences in memory. Midway through the creative process, one may have made associations between the current task and previous experiences but not yet disambiguated which aspects of those previous experiences are relevant to the current task. Thus, the creative idea may feel "half-baked.". At that point, it can be said to be in a potentiality state, because how it will actualize depends on the different internally or externally generated contexts it interacts with.

Honing theory is held to explain certain phenomena not dealt with by other theories of creativity—for example, how different works by the same creator exhibit a recognizable style or "voice" even in different creative outlets. This is not predicted by theories of creativity that emphasize chance processes or the accumulation of expertise, but it is predicted by honing theory, according to which personal style reflects the creator's uniquely structured worldview. Another example is the environmental stimulus for creativity. Creativity is commonly considered to be fostered by a supportive, nurturing, and trustworthy environment conducive to self-actualization. In line with this idea, Gabora posits that creativity is a product of culture and that our social interactions evolve our culture in way that promotes creativity.[60]

Information Intersection

Information intersection is to seek creative conception from various combinations and connections of information elements such as structure, function, and material through systematic decomposition of the information elements of things. It includes different forms of information intersection such as autosomal intersection, heterosomal intersection, multibody intersection and multi-system intersection. The extent to which this ability is applied includes the steps of identifying the object of study, introducing the information response field, breaking down the constituent elements, conducting the information intersection, and evaluating the choices.[61]

The information intersection competence has applications in many fields. In the field of innovation and design, it can help people find new ideas and solutions. In product development, it can help teams combine different technologies, materials and features to create more competitive and innovative products. In planning and management, it can help integrate different resources and elements to develop effective planning and management strategies. In education and training, it can help students and trainers to intersect different knowledge and concepts to facilitate learning and understanding. In entrepreneurship and business development, it can help start-ups and entrepreneurs to intersect different business models, market trends, and consumer needs to identify business opportunities and create competitive advantages. In scientific research, it can help scientists to intersect different theories, experimental results and data to drive scientific development and innovation.

Examples of information intersection capabilities include innovative design, interdisciplinary research, cross-industry collaboration, educational innovation, and business entrepreneurship. By intersecting different elements of information, people can create new ideas, solutions, and innovations.

The ability to intersect information is an important capability that helps people think and create from different perspectives and domains when faced with complex problems and challenges. By nurturing and developing this capability, individuals and organisations can better adapt to change and innovation, and achieve sustained growth and success.

Everyday imaginative thought

In everyday thought, people often spontaneously imagine alternatives to reality when they think "if only...".[62] Their counterfactual thinking is viewed as an example of everyday creative processes.[63] It has been proposed that the creation of counterfactual alternatives to reality depends on similar cognitive processes to rational thought.[64]

Imaginative thought in everyday life can be categorized based on whether it involves perceptual/motor related mental imagery, novel combinatorial processing, or altered psychological states. This classification aids in understanding the neural foundations and practical implications of imagination. [65]

Creative thinking is a central aspect of everyday life, encompassing both controlled and undirected processes. This includes divergent thinking and stage models, highlighting the importance of extra- and meta-cognitive contributions to imaginative thought. [66]

Brain network dynamics play a crucial role in creative cognition. The default and executive control networks in the brain cooperate during creative tasks, suggesting a complex interaction between these networks in facilitating everyday imaginative thought. [67]

Dialectical theory of creativity

The term "dialectical theory of creativity" dates back to psychoanalyst Daniel Dervin[68] and was later developed into an interdisciplinary theory.[69][page needed] The dialectical theory of creativity starts with the ancient concept that creativity takes place in an interplay between order and chaos. Similar ideas can be found in neuroscience and psychology. Neurobiologically, it can be shown that the creative process takes place in a dynamic interplay between coherence and incoherence that leads to new and usable neuronal networks. Psychology shows how the dialectics of convergent and focused thinking with divergent and associative thinking leads to new ideas and products.[70]

Personality traits like the "Big Five" seem to bedialectically intertwined in[clarification needed] the creative process: emotional instability vs. stability, extraversion vs. introversion, openness vs. reserve, agreeableness vs. antagonism, and disinhibition vs. constraint.[71] The dialectical theory of creativity applies[how?] also to counseling and psychotherapy.[72]

Neuroeconomic framework for creative cognition

Lin and Vartanian developed a neurobiological description of creative cognition.[73] This interdisciplinary framework integrates theoretical principles and empirical results from neuroeconomics, reinforcement learning, cognitive neuroscience, and neurotransmission research on the locus coeruleus system. It describes how decision-making processes studied by neuroeconomists as well as activity in the locus coeruleus system underlie creative cognition and the large-scale brain network dynamics associated with creativity.[74] It suggests that creativity is an optimization and utility-maximization problem that requires individuals to determine the optimal way to exploit and explore ideas (the multi-armed bandit problem). This utility maximization process is thought to be mediated by the locus coeruleus system,[75] and this creativity framework describes how tonic and phasic locus coeruleus activity work in conjunction to facilitate the exploiting and exploring of creative ideas. This framework not only explains previous empirical results but also makes novel and falsifiable predictions at different levels of analysis (ranging from neurobiological to cognitive and personality differences).

Behaviorism theory of creativity

B.F. Skinner attributed creativity to accidental behaviors that are reinforced by the environment.[76] In behaviorism, creativity can be understood as novel or unusual behaviors that are reinforced if they produce a desired outcome.[77] Spontaneous behaviors by living creatures are thought to reflect past learned behaviors. In this way,[78] a behaviorist may say that prior learning caused novel behaviors to be reinforced many times over, and the individual has been shaped to produce increasingly novel behaviors.[79] A creative person, according to this definition, is someone who has been reinforced more often for novel behaviors than others. Behaviorists suggest that anyone can be creative, they just need to be reinforced to learn to produce novel behaviors.

Personal assessment

Psychometric approaches

J. P. Guilford's group,[48] which pioneered the modern psychometric study of creativity, constructed several performance-based tests to measure creativity in 1967:

- Plot Titles

- participants are given the plot of a story and asked to write original titles

- Quick Responses

- a word-association test scored for uncommonness

- Figure Concepts

- participants are given simple drawings of objects and individuals and asked to find qualities or features that are common by two or more drawings; these are scored for uncommonness

- Unusual Uses

- finding unusual uses for common everyday objects such as bricks

- Remote Associations

- participants are asked to find a word between two given words (e.g. Hand _____ Call)

- Remote Consequences

- participants are asked to generate a list of consequences of unexpected events (e.g. loss of gravity)

Guilford was trying to create a model for intellect as a whole, but in doing so, he also created a model for creativity. Guilford made an important assumption for creative research: creativity is not an abstract concept. The idea that creativity is a category rather than a single concept enabled other researchers to look at creativity with a new perspective.[80]

Additionally, Guilford hypothesized one of the first models for the components of creativity. He explained that creativity was a result of having:

- sensitivity to problems, or the ability to recognize problems

- fluency, which encompasses

- ideational fluency, or the ability rapidly to produce a variety of ideas that fulfill stated requirements

- associational fluency, or the ability to generate a list of words, each of which is associated with a given word

- expressional fluency, or the ability to organize words into larger units, such as phrases, sentences, and paragraphs

- flexibility, which encompasses

- spontaneous flexibility, or the ability to demonstrate flexibility

- adaptive flexibility, or the ability to produce responses that are novel and high in quality

This represents the base model which several researchers would alter to produce their new theories of creativity years later.[80] Building on Guilford's work, tests were developed, sometimes called Divergent Thinking (DT) tests, which have been both supported[81] and criticized.[82] For example, Torrance[83] developed the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking in 1966.[81] They involved tasks of divergent thinking and other problem-solving skills, which were scored on:

- Fluency

- the total number of interpretable, meaningful, and relevant ideas generated in response to the stimulus

- Flexibility

- the number of different categories of relevant responses

- Originality

- the statistical rarity of the responses among the test subjects

- Elaboration

- the amount of detail in the responses

Considerable progress has been made in the automated scoring of divergent thinking tests using a semantic approach. When compared to human raters, NLP techniques are reliable and valid for scoring originality.[84] Computer programs were able to achieve a correlation to human graders of 0.60 and 0.72.

Semantic networks also devise originality scores that yield significant correlations with socio-personal measures.[85] A team of researchers led by James C. Kaufman and Mark A. Runco combined expertise in creativity research, natural language processing, computational linguistics, and statistical data analysis to devise a scalable system for computerized automated testing (the SparcIt Creativity Index Testing system). This system enabled automated scoring of DT tests that is reliable, objective, and scalable, thus addressing most of the issues of DT tests that had been found and reported.[82] The resultant computer system was able to achieve a correlation to human graders of 0.73.[86]

Social-personality approach

Researchers have taken a social-personality approach by using personality traits such as independence of judgement, self-confidence, attraction to complexity, aesthetic orientation, and risk-taking as measures of the creativity of people.[35] A meta-analysis by Gregory Feist showed that creative people tend to be "more open to new experiences, less conventional and less conscientious, more self-confident, self-accepting, driven, ambitious, dominant, hostile, and impulsive." Openness, conscientiousness, self-acceptance, hostility, and impulsivity had the strongest effects of the traits listed.[87] Within the framework of the Big Five model of personality, some consistent traits have emerged as being correlated to creativity.[88] Openness to experience is consistently related to[how?] a host of different assessments of creativity.[89] Among the other Big Five traits, research has demonstrated subtle differences between different domains of creativity. Compared to non-artists, artists tend to have higher levels of openness to experience and lower levels of conscientiousness, while scientists are more open to experience, conscientious, and higher in the confidence-dominance facets of extraversion compared to non-scientists.[87]

Self-report questionnairesedit

Biographical methods use quantitative characteristics such as the number of publications, patents, or performances of a work can be credited to a person. While this method was originally developed for highly creative personalities, today it is also available as self-report questionnaires supplemented with frequent, less outstanding creative behaviors such as writing a short story or creating your own recipes. For example, the Creative Achievement Questionnaire, a self-report test that measures creative achievement across ten domains, was described in 2005 and shown to be reliable when compared to other measures of creativity and to independent evaluation of creative output.[90] Besides the English original, it was also used in a Chinese,[91] French,[92] and German[93] version. It is the self-report questionnaire most frequently used in research.[91]

Intelligenceedit

The potential relationship between creativity and intelligence has been of interest since the last half of the twentieth century, when many influential studies—from Getzels & Jackson,[94] Barron,[95] Wallach & Kogan,[96] and Guilford[97] – focused not only on creativity but also on intelligence. This joint focus highlights both the theoretical and practical importance of the relationship: researchers are interested not only if the constructs are related, but also how and why.[98]

There are multiple theories accounting for their relationship, with the three main theories as follows:

- Threshold Theory

- Intelligence is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for creativity. There is a moderate positive relationship between creativity and intelligence until IQ ~120.[95][97]

- Certification Theory

- Creativity is not intrinsically related to intelligence. Instead, individuals are required to meet the requisite level of intelligence in order to gain a certain level of education or work, which then in turn offers the opportunity to be creative. Displays of creativity are moderated by intelligence.[99]

- Interference Theory

- Extremely high intelligence might interfere with creative ability.[100]

Sternberg and O'Hara[101] proposed a framework of five possible relationships between creativity and intelligence:

- Creativity is a subset of intelligence.

- Intelligence is a subset of creativity.

- Creativity and intelligence are overlapping constructs.

- Creativity and intelligence are part of the same construct (coincident sets).

- Creativity and intelligence are distinct constructs (disjoint sets).

Creativity as a subset of intelligenceedit

A number of researchers include creativity, either explicitly or implicitly, as a key component of intelligence, for example:

- Sternberg's Theory of Successful Intelligence[100][101][102] (see Triarchic theory of intelligence) includes creativity as a main component and comprises three sub-theories: contextual (analytic), contextual (practical), and experiential (creative). Experiential sub-theory—the ability to use pre-existing knowledge and skills to solve new and novel problems – is directly related to creativity.

- The Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory (CHC) includes creativity as a subset of intelligence, associated with the broad group factor of long-term storage and retrieval (Glr).[103] Glr narrow abilities relating to creativity include ideational fluency, associational fluency, and originality/creativity. Silvia et al.[104] conducted a study to look at the relationship between divergent thinking and verbal fluency tests and reported that both fluency and originality in divergent thinking were significantly affected by the broad-level Glr factor. Martindale[105] extended the CHC-theory by proposing that people who are creative are also selective in their processing speed. Martindale argues that in the creative process, larger amounts of information are processed more slowly in the early stages, and as a person begins to understand the problem, the processing speed is increased.

- The Dual Process Theory of Intelligence[106] posits a two-factor or type model of intelligence. Type 1 is a conscious process and concerns goal-directed thoughts, which are explained by. Type 2 is an unconscious process, and concerns spontaneous cognition, which encompasses daydreaming and implicit learning ability. Kaufman argues that creativity occurs as a result of Type 1 and Type 2 processes working together in combination. Each type in the creative process can be used to varying degrees.

Intelligence as a subset of creativityedit

In this relationship model, intelligence is a key component in the development of creativity, for example:

- Sternberg & Lubart's Investment Theory,[107][108] using the metaphor of a stock market, demonstrates that creative thinkers are like good investors—they buy low and sell high (in their ideas). Like undervalued or low-valued stock, creative individuals generate unique ideas that are initially rejected by other people. The creative individual has to persevere and convince others of the idea's value. After convincing the others and thus increasing the idea's value, the creative individual'sells high' by leaving the idea with the other people and moves on to generate another idea. According to this theory, six distinct, but related elements contribute to successful creativity: intelligence, knowledge, thinking styles, personality, motivation, and environment. Intelligence is just one of the six factors that can, either solely or in conjunction with the other five factors, generate creative thoughts.

- Amabile's Componential Model of Creativity[109][110] posits three within-individual components needed for creativity—domain-relevant skills, creativity-relevant processes, and task motivation—and one component external to the individual: their surrounding social environment. Creativity requires the confluence of all components. High creativity will result when a person is intrinsically motivated, possesses both a high level of domain-relevant skills and has high skills in creative thinking, and is working in a highly creative environment.

- The Amusement Park Theoretical Model[111] is a four-step theory in which domain-specific and generalist views are integrated into a model of creativity. The researchers make use of the metaphor of the amusement park to demonstrate that within each of the following creative levels, intelligence plays a key role:

- To get into the amusement park, there are initial requirements (e.g., time/transport to go to the park). Initial requirements (like intelligence) are necessary, but not sufficient for creativity. They are more like prerequisites for creativity, and if a person does not possess the basic level of the initial requirement (intelligence), then they will not be able to generate creative thoughts/behaviour.

- Secondly, there are the subcomponents—general thematic areas—that increase in specificity. Like choosing which type of amusement park to visit (e.g., a zoo or a water park), these areas relate to the areas in which someone could be creative (e.g. poetry).

- Thirdly, there are specific domains. After choosing the type of park to visit, e.g., a waterpark, you then have to choose which specific park to go to. For example, within the poetry domain, there are many different types (e.g., free verse, riddles, sonnets, etc.) that have to be selected from.

- Lastly, there are micro-domains. These are the specific tasks that reside within each domain, e.g., individual lines in a free verse poem / individual rides at the waterpark.

Creativity and intelligence as overlapping yet distinct constructsedit

This possible relationship concerns creativity and intelligence as distinct, but intersecting constructs, for example:

- In Renzulli's Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness,[112] giftedness is an overlap of above-average intellectual ability, creativity, and task commitment. Under this view, creativity and intelligence are distinct constructs, but they overlap under the correct conditions.

- In the PASS theory of intelligence, the planning component—the ability to solve problems, make decisions, and take action – strongly overlaps with the concept of creativity.[113]

- Threshold Theory (TT) derives from a number of previous research findings that suggested that a threshold exists in the relationship between creativity and intelligence – both constructs are moderately positively correlated up to an IQ of ~120. Above this threshold, if there is a relationship at all, it is small and weak.[94][95][114] TT posits that a moderate level of intelligence is necessary for creativity.

In support of TT, Barron[95][115] found a non-significant correlation between creativity and intelligence in a gifted sample and a significant correlation in a non-gifted sample. Yamamoto,[116] in a sample of secondary school children, reported a significant correlation between creativity and intelligence of r = 0.3 and reported no significant correlation when the sample consisted of gifted children. Fuchs-Beauchamp et al.,[117] in a sample of preschoolers, found that creativity and intelligence correlated from r = 0.19 to r = 0.49 in the group of children who had an IQ below the threshold, and in the group above the threshold, the correlations were r = 0.12. Cho et al.[118] reported a correlation of 0.40 between creativity and intelligence in the average IQ group of a sample of adolescents and adults and a correlation of close to r=0.0 for the high IQ group. Jauk et al.[119] found support for the TT, but only for measures of creative potential, not creative performance.

By contrast, other research reports findings against TT. Wai et al.,[120] using data from the longitudinal Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth—a cohort of elite students from early adolescence into adulthood—found that differences in SAT scores at age 13 were predictive of creative real-life outcomes[definition needed] 20 years later. Kim's[121] meta-analysis of 21 studies did not find any supporting evidence for TT, and instead negligible correlations were reported between intelligence, creativity, and divergent thinking both below and above IQ's of 120. Preckel et al.,[122] investigating fluid intelligence and creativity, reported small correlations of r = 0.3 to r=0.4 across all levels of cognitive ability.

Creativity and intelligence as coincident setsedit

Under this view, researchers posit that there are no differences in the mechanisms underlying creativity between those used in normal problem solving, and in normal problem solving, there is no need for creativity. Thus, creativity and intelligence (problem solving) are the same thing. Perkins[123] referred to this as the "nothing-special" view.

Weisberg & Alba[124] examined problem solving by having participants complete the nine dots puzzle – where the participants are asked to connect all nine dots in the three rows of three dots using four straight lines or less without lifting their pen or tracing the same line twice. The problem can only be solved if the lines go outside the boundaries of the square of dots. Results demonstrated that even when participants were given this insight, they still found it difficult to solve the problem, thus showing that to successfully complete the task it is not just insight (or creativity) that is required.

Creativity and intelligence as disjoint setsedit

In this view, creativity and intelligence are completely different, unrelated constructs.

Getzels and Jackson[94] administered five creativity measures to a group of 449 children from grades 6–12[globalize] and compared these test findings to results from previously administered (by the school) IQ tests. They found that the correlation between the creativity measures and IQ was r=0.26. The high creativity group scored in the top 20% of the overall creativity measures but was not included in the top 20% of IQ scorers. The high intelligence group scored the opposite: they scored in the top 20% for IQ, but were outside the top 20% scorers for creativity, thus showing that creativity and intelligence are distinct and unrelated.

However, this work has been heavily criticized. Wallach and Kogan[96] highlighted that the creativity measures were not only weakly related to one another (to the extent that they were no more related to one another than they were to IQ), but they seemed to also draw upon non-creative skills. McNemar[125] noted that there were major measurement issues in that the IQ scores were a mixture from three different IQ tests.

Wallach and Kogan[96] administered five measures of creativity, each of which resulted in a score for originality and fluency; and ten measures of general intelligence to 151 5th grade[globalize] children. These tests were untimed, and given in a game-like manner (aiming to facilitate creativity). Inter-correlations between creativity tests were on average r=0.41. Inter-correlations between intelligence measures were on average r=0.51 with each other. Creativity tests and intelligence measures correlated r=0.09.

Neuroscienceedit

The neuroscience of creativity looks at the operation of the brain during creative behavior. It has been addressed in the article "Creative Innovation: Possible Brain Mechanisms".[126] The authors write that "creative innovation might require coactivation and communication between regions of the brain that ordinarily are not strongly connected." Highly creative people who excel at creative innovation tend to differ from others in three ways:

- they have a high level of specialized knowledge

- they are capable of divergent thinking mediated by the frontal lobe

- they are able to modulate neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine in their frontal lobe

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk