A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any vessel or a particular vessel type, akin to anti-infantry or anti-vehicle mines. Naval mines can be used offensively, to hamper enemy shipping movements or lock vessels into a harbour; or defensively, to protect friendly vessels and create "safe" zones. Mines allow the minelaying force commander to concentrate warships or defensive assets in mine-free areas giving the adversary three choices: undertake an expensive and time-consuming minesweeping effort, accept the casualties of challenging the minefield, or use the unmined waters where the greatest concentration of enemy firepower will be encountered.[1]

Although international law requires signatory nations to declare mined areas, precise locations remain secret, and non-complying individuals might not disclose minelaying. While mines threaten only those who choose to traverse waters that may be mined, the possibility of activating a mine is a powerful disincentive to shipping. In the absence of effective measures to limit each mine's lifespan, the hazard to shipping can remain long after the war in which the mines were laid is over. Unless detonated by a parallel time fuze at the end of their useful life, naval mines need to be found and dismantled after the end of hostilities; an often prolonged, costly, and hazardous task.

Modern mines containing high explosives detonated by complex electronic fuze mechanisms are much more effective than early gunpowder mines requiring physical ignition. Mines may be placed by aircraft, ships, submarines, or individual swimmers and boatmen. Minesweeping is the practice of the removal of explosive naval mines, usually by a specially designed ship called a minesweeper using various measures to either capture or detonate the mines, but sometimes also with an aircraft made for that purpose. There are also mines that release a homing torpedo rather than explode themselves.

Description

Mines can be laid in many ways: by purpose-built minelayers, refitted ships, submarines, or aircraft—and even by dropping them into a harbour by hand. They can be inexpensive: some variants can cost as little as US $2,000, though more sophisticated mines can cost millions of dollars, be equipped with several kinds of sensors, and deliver a warhead by rocket or torpedo.

Their flexibility and cost-effectiveness make mines attractive to the less powerful belligerent in asymmetric warfare. The cost of producing and laying a mine is usually between 0.5% and 10% of the cost of removing it, and it can take up to 200 times as long to clear a minefield as to lay it. Parts of some World War II naval minefields still exist because they are too extensive and expensive to clear.[2] Some 1940s-era mines may remain dangerous for many years.[3]

Mines have been employed as offensive or defensive weapons in rivers, lakes, estuaries, seas, and oceans, but they can also be used as tools of psychological warfare. Offensive mines are placed in enemy waters, outside harbours, and across important shipping routes to sink both merchant and military vessels. Defensive minefields safeguard key stretches of coast from enemy ships and submarines, forcing them into more easily defended areas, or keeping them away from sensitive ones.

Shipowners are reluctant to send their ships through known minefields. Port authorities may attempt to clear a mined area, but those without effective minesweeping equipment may cease using the area. Transit of a mined area will be attempted only when strategic interests outweigh potential losses. The decision-makers' perception of the minefield is a critical factor. Minefields designed for psychological effect are usually placed on trade routes to stop ships from reaching an enemy nation. They are often spread thinly, to create an impression of minefields existing across large areas. A single mine inserted strategically on a shipping route can stop maritime movements for days while the entire area is swept. A mine's capability to sink ships makes it a credible threat, but minefields work more on the mind than on ships.[4]

International law, specifically the Eighth Hague Convention of 1907, requires nations to declare when they mine an area, to make it easier for civil shipping to avoid the mines. The warnings do not have to be specific; for example, during World War II, Britain declared simply that it had mined the English Channel, North Sea and French coast.

History

Early use

Naval mines were first invented by Chinese innovators of Imperial China and were described in thorough detail by the early Ming dynasty artillery officer Jiao Yu, in his 14th-century military treatise known as the Huolongjing.[5] Chinese records tell of naval explosives in the 16th century, used to fight against Japanese pirates (wokou). This kind of naval mine was loaded in a wooden box, sealed with putty. General Qi Jiguang made several timed, drifting explosives, to harass Japanese pirate ships.[6] The Tiangong Kaiwu (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature) treatise, written by Song Yingxing in 1637, describes naval mines with a ripcord pulled by hidden ambushers located on the nearby shore who rotated a steel wheel flint mechanism to produce sparks and ignite the fuse of the naval mine.[7] Although this is the rotating steel wheel's first use in naval mines, Jiao Yu described their use for land mines in the 14th century.[8]

The first plan for a sea mine in the West was by Ralph Rabbards, who presented his design to Queen Elizabeth I of England in 1574.[7] The Dutch inventor Cornelius Drebbel was employed in the Office of Ordnance by King Charles I of England to make weapons, including the failed "floating petard".[9] Weapons of this type were apparently tried by the English at the Siege of La Rochelle in 1627.[10]

American David Bushnell developed the first American naval mine, for use against the British in the American War of Independence.[11] It was a watertight keg filled with gunpowder that was floated toward the enemy, detonated by a sparking mechanism if it struck a ship. It was used on the Delaware River as a drift mine, destroying a small boat near its intended target, a British warship.[12]

The 19th century

The 1804 Raid on Boulogne made extensive use of explosive devices designed by inventor Robert Fulton. The 'torpedo-catamaran' was a coffer-like device balanced on two wooden floats and steered by a man with a paddle. Weighted with lead so as to ride low in the water, the operator was further disguised by wearing dark clothes and a black cap.[13] His task was to approach the French ship, hook the torpedo to the anchor cable and, having activated the device by removing a pin, remove the paddles and escape before the torpedo detonated.[14] Also to be deployed were large numbers of casks filled with gunpowder, ballast and combustible balls. They would float in on the tide and on washing up against an enemy's hull, explode.[14] Also included in the force were several fireships, carrying 40 barrels of gunpowder and rigged to explode by a clockwork mechanism.[14]

In 1812, Russian engineer Pavel Shilling exploded an underwater mine using an electrical circuit. In 1842 Samuel Colt used an electric detonator to destroy a moving vessel to demonstrate an underwater mine of his own design to the United States Navy and President John Tyler. However, opposition from former president John Quincy Adams, scuttled the project as "not fair and honest warfare".[15] In 1854, during the unsuccessful attempt of the Anglo-French (101 warships) fleet to seize the Kronstadt fortress, British steamships HMS Merlin (9 June 1855, the first successful mining in history), HMS Vulture and HMS Firefly suffered damage due to the underwater explosions of Russian naval mines. Russian naval specialists set more than 1,500 naval mines, or infernal machines, designed by Moritz von Jacobi and by Immanuel Nobel,[16] in the Gulf of Finland during the Crimean War of 1853–1856. The mining of Vulcan led to the world's first minesweeping operation.[17][18] During the next 72 hours, 33 mines were swept.[19]

The Jacobi mine was designed by German-born, Russian engineer Jacobi, in 1853. The mine was tied to the sea bottom by an anchor. A cable connected it to a galvanic cell which powered it from the shore, the power of its explosive charge was equal to 14 kg (31 lb) of black powder. In the summer of 1853, the production of the mine was approved by the Committee for Mines of the Ministry of War of the Russian Empire. In 1854, 60 Jacobi mines were laid in the vicinity of the Forts Pavel and Alexander (Kronstadt), to deter the British Baltic Fleet from attacking them. It gradually phased out its direct competitor the Nobel mine on the insistence of Admiral Fyodor Litke. The Nobel mines were bought from Swedish industrialist Immanuel Nobel who had entered into collusion with the Russian head of navy Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov. Despite their high cost (100 Russian rubles) the Nobel mines proved to be faulty, exploding while being laid, failing to explode or detaching from their wires, and drifting uncontrollably, at least 70 of them were subsequently disarmed by the British. In 1855, 301 more Jacobi mines were laid around Krostadt and Lisy Nos. British ships did not dare to approach them.[20]

In the 19th century, mines were called torpedoes, a name probably conferred by Robert Fulton after the torpedo fish, which gives powerful electric shocks. A spar torpedo was a mine attached to a long pole and detonated when the ship carrying it rammed another one and withdrew a safe distance. The submarine H. L. Hunley used one to sink USS Housatonic on 17 February 1864. A Harvey torpedo was a type of floating mine towed alongside a ship and was briefly in service in the Royal Navy in the 1870s. Other "torpedoes" were attached to ships or propelled themselves. One such weapon called the Whitehead torpedo after its inventor, caused the word "torpedo" to apply to self-propelled underwater missiles as well as to static devices. These mobile devices were also known as "fish torpedoes".

The American Civil War of 1861–1865 also saw the successful use of mines. The first ship sunk by a mine, USS Cairo, foundered in 1862 in the Yazoo River. Rear Admiral David Farragut's famous/apocryphal command during the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!" refers to a minefield laid at Mobile, Alabama.

After 1865 the United States adopted the mine as its primary weapon for coastal defense. In the decade following 1868, Major Henry Larcom Abbot carried out a lengthy set of experiments to design and test moored mines that could be exploded on contact or be detonated at will as enemy shipping passed near them. This initial development of mines in the United States took place under the purview of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which trained officers and men in their use at the Engineer School of Application at Willets Point, New York (later named Fort Totten). In 1901 underwater minefields became the responsibility of the US Army's Artillery Corps, and in 1907 this was a founding responsibility of the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps.[21]

The Imperial Russian Navy, a pioneer in mine warfare, successfully deployed mines against the Ottoman Navy during both the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878).[22]

During the War of the Pacific (1879-1883), the Peruvian Navy, at a time when the Chilean squadron was blockading the Peruvian ports, formed a brigade of torpedo boats under the command of the frigate captain Leopoldo Sánchez Calderón and the Peruvian engineer Manuel Cuadros, who perfected the naval torpedo or mine system to be electrically activated when the cargo weight was lifted. This is how, on July 3, 1880, in front of the port of Callao, the gunned transport Loa flies when capturing a sloop mined by the Peruvians. A similar fate occurred with the gunboat schooner Covadonga in front of the port of Chancay, on September 13, 1880, which having captured and checked a beautiful boat, it exploded when hoisting it on its side.[23]

During the Battle of Tamsui (1884), in the Keelung Campaign of the Sino-French War, Chinese forces in Taiwan under Liu Mingchuan took measures to reinforce Tamsui against the French; they planted nine torpedo mines in the river and blocked the entrance.[24]

Early 20th century

During the Boxer Rebellion, Imperial Chinese forces deployed a command-detonated mine field at the mouth of the Hai River before the Dagu forts, to prevent the western Allied forces from sending ships to attack.[25][26]

The next major use of mines was during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Two mines blew up when the Petropavlovsk struck them near Port Arthur, sending the holed vessel to the bottom and killing the fleet commander, Admiral Stepan Makarov, and most of his crew in the process. The toll inflicted by mines was not confined to the Russians, however. The Japanese Navy lost two battleships, four cruisers, two destroyers and a torpedo-boat to offensively laid mines during the war. Most famously, on 15 May 1904, the Russian minelayer Amur planted a 50-mine minefield off Port Arthur and succeeded in sinking the Japanese battleships Hatsuse and Yashima.

Following the end of the Russo-Japanese War, several nations attempted to have mines banned as weapons of war at the Hague Peace Conference (1907).[22]

Many early mines were fragile and dangerous to handle, as they contained glass containers filled with nitroglycerin or mechanical devices that activated a blast upon tipping. Several mine-laying ships were destroyed when their cargo exploded.[27]

Beginning around the start of the 20th century, submarine mines played a major role in the defense of U.S. harbours against enemy attacks as part of the Endicott and Taft Programs. The mines employed were controlled mines, anchored to the bottoms of the harbours, and detonated under control from large mine casemates onshore.

During World War I, mines were used extensively to defend coasts, coastal shipping, ports and naval bases around the globe. The Germans laid mines in shipping lanes to sink merchant and naval vessels serving Britain. The Allies targeted the German U-boats in the Strait of Dover and the Hebrides. In an attempt to seal up the northern exits of the North Sea, the Allies developed the North Sea Mine Barrage. During a period of five months from June 1918, almost 70,000 mines were laid spanning the North Sea's northern exits. The total number of mines laid in the North Sea, the British East Coast, Straits of Dover, and Heligoland Bight is estimated at 190,000 and the total number during the whole of WWI was 235,000 sea mines.[28] Clearing the barrage after the war took 82 ships and five months, working around the clock.[29] It was also during World War I, that the British hospital ship, HMHS Britannic, became the largest vessel ever sunk by a naval mine[citation needed]. The Britannic was the sister ship of the RMS Titanic, and the RMS Olympic.[30]

World War II

During World War II, the U-boat fleet, which dominated much of the battle of the Atlantic, was small at the beginning of the war and much of the early action by German forces involved mining convoy routes and ports around Britain. German submarines also operated in the Mediterranean Sea, in the Caribbean Sea, and along the U.S. coast.

Initially, contact mines (requiring a ship to physically strike a mine to detonate it) were employed, usually tethered at the end of a cable just below the surface of the water. Contact mines usually blew a hole in ships' hulls. By the beginning of World War II, most nations had developed mines that could be dropped from aircraft, some of which floated on the surface, making it possible to lay them in enemy harbours. The use of dredging and nets was effective against this type of mine, but this consumed valuable time and resources and required harbours to be closed.

Later, some ships survived mine blasts, limping into port with buckled plates and broken backs. This appeared to be due to a new type of mine, detecting ships by their proximity to the mine (an influence mine) and detonating at a distance, causing damage with the shock wave of the explosion. Ships that had successfully run the gantlet of the Atlantic crossing were sometimes destroyed entering freshly cleared British harbours. More shipping was being lost than could be replaced, and Churchill ordered the intact recovery of one of these new mines to be of the highest priority.

The British experienced a stroke of luck in November 1939, when a German mine was dropped from an aircraft onto the mudflats off Shoeburyness during low tide. Additionally, the land belonged to the army and a base with men and workshops was at hand. Experts were dispatched from HMS Vernon to investigate the mine. The Royal Navy knew that mines could use magnetic sensors, Britain having developed magnetic mines in World War I, so everyone removed all metal, including their buttons, and made tools of non-magnetic brass.[31] They disarmed the mine and rushed it to the labs at HMS Vernon, where scientists discovered that the mine had a magnetic arming mechanism. A large ferrous object passing through the Earth's magnetic field will concentrate the field through it, due to its magnetic permeability; the mine's detector was designed to trigger as a ship passed over when the Earth's magnetic field was concentrated in the ship and away from the mine. The mine detected this loss of the magnetic field which caused it to detonate. The mechanism had an adjustable sensitivity, calibrated in milligauss.

From this data, known methods were used to clear these mines. Early methods included the use of large electromagnets dragged behind ships or below low-flying aircraft (a number of older bombers like the Vickers Wellington were used for this). Both of these methods had the disadvantage of "sweeping" only a small strip. A better solution was found in the "Double-L Sweep"[32] using electrical cables dragged behind ships that passed large pulses of current through the seawater. This created a large magnetic field and swept the entire area between the two ships. The older methods continued to be used in smaller areas. The Suez Canal continued to be swept by aircraft, for instance.

While these methods were useful for clearing mines from local ports, they were of little or no use for enemy-controlled areas. These were typically visited by warships, and the majority of the fleet then underwent a massive degaussing process, where their hulls had a slight "south" bias induced into them which offset the concentration-effect almost to zero.

Initially, major warships and large troopships had a copper degaussing coil fitted around the perimeter of the hull, energized by the ship's electrical system whenever in suspected magnetic-mined waters. Some of the first to be so fitted were the carrier HMS Ark Royal and the liners RMS Queen Mary and RMS Queen Elizabeth. It was a photo of one of these liners in New York harbour, showing the degaussing coil, which revealed to German Naval Intelligence the fact that the British were using degaussing methods to combat their magnetic mines.[33] This was felt to be impractical for smaller warships and merchant vessels, mainly because the ships lacked the generating capacity to energise such a coil. It was found that "wiping" a current-carrying cable up and down a ship's hull[34] temporarily canceled the ships' magnetic signature sufficiently to nullify the threat. This started in late 1939, and by 1940 merchant vessels and the smaller British warships were largely immune for a few months at a time until they once again built up a field.

The cruiser HMS Belfast is just one example of a ship that was struck by a magnetic mine during this time. On 21 November 1939, a mine broke her keel, which damaged her engine and boiler rooms, as well as injuring 46 men, with one man later dying from his injuries. She was towed to Rosyth for repairs. Incidents like this resulted in many of the boats that sailed to Dunkirk being degaussed in a marathon four-day effort by degaussing stations.[35]

The Allies and Germany deployed acoustic mines in World War II, against which even wooden-hulled ships (in particular minesweepers) remained vulnerable.[36] Japan developed sonic generators to sweep these; the gear was not ready by war's end.[36] The primary method Japan used was small air-delivered bombs. This was profligate and ineffectual; used against acoustic mines at Penang, 200 bombs were needed to detonate just 13 mines.[36]

The Germans developed a pressure-activated mine and planned to deploy it as well, but they saved it for later use when it became clear the British had defeated the magnetic system. The U.S. also deployed these, adding "counters" which would allow a variable number of ships to pass unharmed before detonating.[36] This made them a great deal harder to sweep.[36]

Mining campaigns could have devastating consequences. The U.S. effort against Japan, for instance, closed major ports, such as Hiroshima, for days,[37] and by the end of the Pacific War had cut the amount of freight passing through Kobe–Yokohama by 90%.[37]

When the war ended, more than 25,000 U.S.-laid mines were still in place, and the Navy proved unable to sweep them all, limiting efforts to critical areas.[38] After sweeping for almost a year, in May 1946, the Navy abandoned the effort with 13,000 mines still unswept.[38] Over the next thirty years, more than 500 minesweepers (of a variety of types) were damaged or sunk clearing them.[38]

The U.S. began adding delay counters to their magnetic mines in June 1945.[39]

Cold War era

Since World War II, mines have damaged 14 United States Navy ships, whereas air and missile attacks have damaged four. During the Korean War, mines laid by North Korean forces caused 70% of the casualties suffered by U.S. naval vessels and caused 4 sinkings.[40]

During the Iran–Iraq War from 1980 to 1988, the belligerents mined several areas of the Persian Gulf and nearby waters. On 24 July 1987, the supertanker SS Bridgeton was mined by Iran near Farsi Island. On 14 April 1988, USS Samuel B. Roberts struck an Iranian mine in the central Persian Gulf shipping lane, wounding 10 sailors.

In the summer of 1984, magnetic sea mines damaged at least 19 ships in the Red Sea. The U.S. concluded Libya was probably responsible for the minelaying.[41] In response the U.S., Britain, France, and three other nations[42] launched Operation Intense Look, a minesweeping operation in the Red Sea involving more than 46 ships.[43]

On the orders of the Reagan administration, the CIA mined Nicaragua's Sandino port in 1984 in support of the Contra terrorist group.[44] A Soviet tanker was among the ships damaged by these mines.[45] In 1986, in the case of Nicaragua v. United States, the International Court of Justice ruled that this mining was a violation of international law.

Post Cold War

During the Gulf War, Iraqi naval mines severely damaged USS Princeton and USS Tripoli.[46] When the war concluded, eight countries conducted clearance operations.[42]

Houthi forces in the Yemeni Civil War have made frequent use of naval mines, laying over 150 in the Red Sea throughout the conflict.[47]

In the first month of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ukraine accused Russia of deliberately employing drifting mines in the Black Sea area. Around the same time, Turkish and Romanian military diving teams were involved in defusing operations, when stray mines were spotted near the coasts of these countries. London P&I Club issued a warning to freight ships in the area, advising them to "maintain lookouts for mines and pay careful attention to local navigation warnings".[48] Ukrainian forces have mined "from the Sea of Azov to the Black Sea which banks the critical city of Odesa."[49]

Types

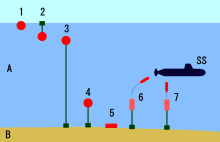

A-underwater, B-bottom, SS-submarine. 1-drifting mine, 2-drifting mine, 3-moored mine, 4-moored mine (short wire), 5-bottom mines, 6-torpedo mine/CAPTOR mine, 7-rising mine

Naval mines may be classified into three major groups; contact, remote and influence mines.

Contact mines

The earliest mines were usually of this type. They are still used today, as they are extremely low cost compared to any other anti-ship weapon and are effective, both as a psychological weapon and as a method to sink enemy ships. Contact mines need to be touched by the target before they detonate, limiting the damage to the direct effects of the explosion and usually affecting only the vessel that triggers them.

Early mines had mechanical mechanisms to detonate them, but these were superseded in the 1870s by the "Hertz horn" (or "chemical horn"), which was found to work reliably even after the mine had been in the sea for several years. The mine's upper half is studded with hollow lead protuberances, each containing a glass vial filled with sulfuric acid. When a ship's hull crushes the metal horn, it cracks the vial inside it, allowing the acid to run down a tube and into a lead–acid battery which until then contained no acid electrolyte. This energizes the battery, which detonates the explosive.[50]

Earlier forms of the detonator employed a vial of sulfuric acid surrounded by a mixture of potassium perchlorate and sugar. When the vial was crushed, the acid ignited the perchlorate-sugar mix, and the resulting flame ignited the gunpowder charge.[51]

During the initial period of World War I, the Royal Navy used contact mines in the English Channel and later in large areas of the North Sea to hinder patrols by German submarines. Later, the American antenna mine was widely used because submarines could be at any depth from the surface to the seabed. This type of mine had a copper wire attached to a buoy that floated above the explosive charge which was weighted to the seabed with a steel cable. If a submarine's steel hull touched the copper wire, the slight voltage change caused by contact between two dissimilar metals was amplified[clarification needed] and detonated the explosives.[50]

Limpet mines

Limpet mines are a special form of contact mine that are manually attached to the target by magnets and remain in place. They are named because of the similarity to the limpet, a mollusk.

Moored contact mines

Generally, this type of mine is set to float just below the surface of the water or as deep as five meters. A steel cable connecting the mine to an anchor on the seabed prevents it from drifting away. The explosive and detonating mechanism is contained in a buoyant metal or plastic shell. The depth below the surface at which the mine floats can be set so that only deep draft vessels such as aircraft carriers, battleships or large cargo ships are at risk, saving the mine from being used on a less valuable target. In littoral waters it is important to ensure that the mine does not become visible when the sea level falls at low tide, so the cable length is adjusted to take account of tides. During WWII there were mines that could be moored in 300 m (980 ft)-deep water.

Floating mines typically have a mass of around 200 kg (440 lb), including 80 kg (180 lb) of explosives e.g. TNT, minol or amatol.[52]

Moored contact mines with plummet

A special form of moored contact mines are those equipped with a plummet. When the mine is launched (1), the mine with the anchor floats first and the lead plummet sinks from it (2). In doing so, the plummet unwinds a wire, the deep line, which is used to set the depth of the mine below the water surface before it is launched (3). When the deep line has been unwound to a set length, the anchor is flooded and the mine is released from the anchor (4). The anchor begins to sink and the mooring cable unwinds until the plummet reaches the sea floor (5). Triggered by the decreasing tension on the deep line, the mooring cable is clamped. The anchor continues sinking down to the bottom of the sea, pulling the mine below the water surface to a depth equal to the length of the deep line (6). Thus, even without knowing the exact seafloor depth, an exact depth of the mine below the water surface can be set, limited only by the maximum length of the mooring cable.

Drifting contact mines

Drifting mines were occasionally used during World War I and World War II. However, they were more feared than effective. Sometimes floating mines break from their moorings and become drifting mines; modern mines are designed to deactivate in this event. After several years at sea, the deactivation mechanism might not function as intended and the mines may remain live. Admiral Jellicoe's British fleet did not pursue and destroy the outnumbered German High Seas Fleet when it turned away at the Battle of Jutland because he thought they were leading him into a trap: he believed it possible that the Germans were either leaving floating mines in their wake, or were drawing him towards submarines, although neither of these was the case.

After World War I the drifting contact mine was banned, but was occasionally used during World War II. The drifting mines were much harder to remove than tethered mines after the war, and they caused about the same damage to both sides.[53]

Churchill promoted "Operation Royal Marine" in 1940 and again in 1944 where floating mines were put into the Rhine in France to float down the river, becoming active after a time calculated to be long enough to reach German territory.

Remotely controlled mines

Frequently used in combination with coastal artillery and hydrophones, controlled mines (or command detonation mines) can be in place in peacetime, which is a huge advantage in blocking important shipping routes. The mines can usually be turned into "normal" mines with a switch (which prevents the enemy from simply capturing the controlling station and deactivating the mines), detonated on a signal or be allowed to detonate on their own. The earliest ones were developed around 1812 by Robert Fulton. The first remotely controlled mines were moored mines used in the American Civil War, detonated electrically from shore. They were considered superior to contact mines because they did not put friendly shipping at risk.[54] The extensive American fortifications program initiated by the Board of Fortifications in 1885 included remotely controlled mines, which were emplaced or in reserve from the 1890s until the end of World War II.[55]

Modern examples usually weigh 200 kg (440 lb), including 80 kg (180 lb) of explosives (TNT or torpex).[citation needed]

Influence mines

These mines are triggered by the influence of a ship or submarine, rather than direct contact. Such mines incorporate electronic sensors designed to detect the presence of a vessel and detonate when it comes within the blast range of the warhead. The fuses on such mines may incorporate one or more of the following sensors: magnetic, passive acoustic or water pressure displacement caused by the proximity of a vessel.[56]

First used during WWI, their use became more general in WWII. The sophistication of influence mine fuses has increased considerably over the years as first transistors and then microprocessors have been incorporated into designs. Simple magnetic sensors have been superseded by total-field magnetometers. Whereas early magnetic mine fuses would respond only to changes in a single component of a target vessel's magnetic field, a total field magnetometer responds to changes in the magnitude of the total background field (thus enabling it to better detect even degaussed ships). Similarly, the original broadband hydrophones of 1940s acoustic mines (which operate on the integrated volume of all frequencies) have been replaced by narrow-band sensors which are much more sensitive and selective. Mines can now be programmed to listen for highly specific acoustic signatures (e.g. a gas turbine powerplant or cavitation sounds from a particular design of propeller) and ignore all others. The sophistication of modern electronic mine fuzes incorporating these digital signal processing capabilities makes it much more difficult to detonate the mine with electronic countermeasures because several sensors working together (e.g. magnetic, passive acoustic and water pressure) allow it to ignore signals which are not recognised as being the unique signature of an intended target vessel.[57]

Modern influence mines such as the BAE Stonefish are computerised, with all the programmability this implies, such as the ability to quickly load new acoustic signatures into fuses, or program them to detect a single, highly distinctive target signature. In this way, a mine with a passive acoustic fuze can be programmed to ignore all friendly vessels and small enemy vessels, only detonating when a very large enemy target passes over it. Alternatively, the mine can be programmed specifically to ignore all surface vessels regardless of size and exclusively target submarines.

Even as far back as WWII it was possible to incorporate a "ship counter" function in mine fuzes. This might set the mine to ignore the first two ships passing over it (which could be minesweepers deliberately trying to trigger mines) but detonate when the third ship passes overhead, which could be a high-value target such as an aircraft carrier or oil tanker. Even though modern mines are generally powered by a long life lithium battery, it is important to conserve power because they may need to remain active for months or even years. For this reason, most influence mines are designed to remain in a semi-dormant state until an unpowered (e.g. deflection of a mu-metal needle) or low-powered sensor detects the possible presence of a vessel, at which point the mine fuze powers up fully and the passive acoustic sensors will begin to operate for some minutes. It is possible to program computerised mines to delay activation for days or weeks after being laid. Similarly, they can be programmed to self-destruct or render themselves safe after a preset period of time. Generally, the more sophisticated the mine design, the more likely it is to have some form of anti-handling device to hinder clearance by divers or remotely piloted submersibles.[57][58]

Moored mines

The moored mine is the backbone of modern mine systems. They are deployed where water is too deep for bottom mines. They can use several kinds of instruments to detect an enemy, usually a combination of acoustic, magnetic and pressure sensors, or more sophisticated optical shadows or electro potential sensors. These cost many times more than contact mines. Moored mines are effective against most kinds of ships. As they are cheaper than other anti-ship weapons they can be deployed in large numbers, making them useful area denial or "channelizing" weapons. Moored mines usually have lifetimes of more than 10 years, and some almost unlimited. These mines usually weigh 200 kg (440 lb), including 80 kg (180 lb) of explosives (RDX). In excess of 150 kg (330 lb) of explosives the mine becomes inefficient, as it becomes too large to handle and the extra explosives add little to the mine's effectiveness.[citation needed]

Bottom mines

Bottom mines (sometimes called ground mines) are used when the water is no more than 60 meters (200 feet) deep or when mining for submarines down to around 200 meters (660 feet). They are much harder to detect and sweep, and can carry a much larger warhead than a moored mine. Bottom mines commonly use multiple types of sensors, which are less sensitive to sweeping.[58][59]

These mines usually weigh between 150 and 1,500 kg (330 and 3,310 lb), including between 125 and 1,400 kg (276 and 3,086 lb) of explosives.[60]

Unusual mines

Several specialized mines have been developed for other purposes than the common minefield.

Bouquet mine

The bouquet mine is a single anchor attached to several floating mines. It is designed so that when one mine is swept or detonated, another takes its place. It is a very sensitive construction and lacks reliability.

Anti-sweep mine

The anti-sweep mine is a very small mine (40 kg (88 lb) warhead) with as small a floating device as possible. When the wire of a mine sweep hits the anchor wire of the mine, it drags the anchor wire along with it, pulling the mine down into contact with the sweeping wire. That detonates the mine and cuts the sweeping wire. They are very cheap and usually used in combination with other mines in a minefield to make sweeping more difficult. One type is the Mark 23 used by the United States during World War II.

Oscillating mine

The mine is hydrostatically controlled to maintain a pre-set depth below the water's surface independently of the rise and fall of the tide.

Ascending mine

The ascending mine is a floating distance mine that may cut its mooring or in some other way float higher when it detects a target. It lets a single floating mine cover a much larger depth range.

Homing mines

These are mines containing a moving weapon as a warhead, either a torpedo or a rocket.

Rocket mineedit

A Russian invention, the rocket mine is a bottom distance mine that fires a homing high-speed rocket (not torpedo) upwards towards the target. It is intended to allow a bottom mine to attack surface ships as well as submarines from a greater depth. One type is the Te-1 rocket propelled mine.

Torpedo mineedit

A torpedo mine is a self-propelled variety, able to lie in wait for a target and then pursue it e.g. the Mark 60 CAPTOR. Generally, torpedo mines incorporate computerised acoustic and magnetic fuzes. The U.S. Mark 24 "mine", code-named Fido, was actually an ASW homing torpedo. The mine designation was disinformation to conceal its function.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Sea_mine

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk