A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Marketing |

|---|

| Brand management |

|---|

| Strategy |

| Culture |

| Positioning |

| Architecture |

A brand is a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that distinguishes one seller's good or service from those of other sellers.[2][3][4][5] Brands are used in business, marketing, and advertising for recognition and, importantly, to create and store value as brand equity for the object identified, to the benefit of the brand's customers, its owners and shareholders.[6] Brand names are sometimes distinguished from generic or store brands.

The practice of branding—in the original literal sense of marking by burning—is thought to have begun with the ancient Egyptians, who are known to have engaged in livestock branding and branded slaves as early as 2,700 BCE.[7][8] Branding was used to differentiate one person's cattle from another's by means of a distinctive symbol burned into the animal's skin with a hot branding iron. If a person stole any of the cattle, anyone else who saw the symbol could deduce the actual owner. The term has been extended to mean a strategic personality for a product or company, so that "brand" now suggests the values and promises that a consumer may perceive and buy into. Over time, the practice of branding objects extended to a broader range of packaging and goods offered for sale including oil, wine, cosmetics, and fish sauce and, in the 21st century, extends even further into services (such as legal, financial and medical), political parties and people (e.g. Lady Gaga and Katy Perry).

In the modern era, the concept of branding has expanded to include deployment by a manager of the marketing and communication techniques and tools that help to distinguish a company or products from competitors, aiming to create a lasting impression in the minds of customers. The key components that form a brand's toolbox include a brand's identity, personality, product design, brand communication (such as by logos and trademarks), brand awareness, brand loyalty, and various branding (brand management) strategies.[9] Many companies believe that there is often little to differentiate between several types of products in the 21st century, hence branding is among a few remaining forms of product differentiation.[10]

Brand equity is the measurable totality of a brand's worth and is validated by observing the effectiveness of these branding components.[11] When a customer is familiar with a brand or favors it incomparably to its competitors, a corporation has reached a high level of brand equity.[11] Brand owners manage their brands carefully to create shareholder value. Brand valuation is a management technique that ascribes a monetary value to a brand.

Etymology

The word brand, originally meaning a burning piece of wood, comes from Middle English brand, meaning "torch",[12][13] from Old English brand.[14] It became to also mean the mark from burning with a branding iron.[12]

History

Branding and labeling have an ancient history. Branding probably began with the practice of branding livestock to deter theft. Images of the branding of cattle occur in ancient Egyptian tombs dating to around 2,700 BCE.[15] Over time, purchasers realized that the brand provided information about origin as well as about ownership, and could serve as a guide to quality. Branding was adapted by farmers, potters, and traders for use on other types of goods such as pottery and ceramics. Forms of branding or proto-branding emerged spontaneously and independently throughout Africa, Asia and Europe at different times, depending on local conditions.[16] Seals, which acted as quasi-brands, have been found on early Chinese products of the Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE); large numbers of seals survive from the Harappan civilization of the Indus Valley (3,300–1,300 BCE) where the local community depended heavily on trade; cylinder seals came into use in Ur in Mesopotamia in around 3,000 BCE, and facilitated the labelling of goods and property; and the use of maker's marks on pottery was commonplace in both ancient Greece and Rome.[16] Identity marks, such as stamps on ceramics, were also used in ancient Egypt.[17]

Diana Twede has argued that the "consumer packaging functions of protection, utility and communication have been necessary whenever packages were the object of transactions".[18] She has shown that amphorae used in Mediterranean trade between 1,500 and 500 BCE exhibited a wide variety of shapes and markings, which consumers used to glean information about the type of goods and the quality. The systematic use of stamped labels dates from around the fourth century BCE. In largely pre-literate society, the shape of the amphora and its pictorial markings conveyed information about the contents, region of origin and even the identity of the producer, which were understood to convey information about product quality.[19] David Wengrow has argued that branding became necessary following the urban revolution in ancient Mesopotamia in the 4th century BCE, when large-scale economies started mass-producing commodities such as alcoholic drinks, cosmetics and textiles. These ancient societies imposed strict forms of quality-control over commodities, and also needed to convey value to the consumer through branding. Producers began by attaching simple stone seals to products which, over time, gave way to clay seals bearing impressed images, often associated with the producer's personal identity thus giving the product a personality.[20] Not all historians agree that these markings are comparable with modern brands or labels, with some suggesting that the early pictorial brands or simple thumbprints used in pottery should be termed proto-brands[21] while other historians argue that the presence of these simple markings does not imply that mature brand management practices operated.[22]

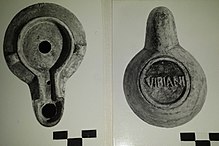

Scholarly studies have found evidence of branding, packaging, and labeling in antiquity.[23][24] Archaeological evidence of potters' stamps has been found across the breadth of the Roman Empire and in ancient Greece. Stamps were used on bricks, pottery, and storage containers as well as on fine ceramics.[25] Pottery marking had become commonplace in ancient Greece by the 6th century BCE. A vase manufactured around 490 BCE bears the inscription "Sophilos painted me", indicating that the object was both fabricated and painted by a single potter.[26] Branding may have been necessary to support the extensive trade in such pots. For example, 3rd-century Gaulish pots bearing the names of well-known potters and the place of manufacture (such as Attianus of Lezoux, Tetturo of Lezoux and Cinnamus of Vichy) have been found as far away as Essex and Hadrian's Wall in England.[27][28][29][30] English potters based at Colchester and Chichester used stamps on their ceramic wares by the 1st century CE.[31] The use of hallmarks, a type of brand, on precious metals dates to around the 4th century CE. A series of five marks occurs on Byzantine silver dating from this period.[32]

Some of the earliest use of maker's marks, dating to about 1,300 BCE, have been found in India.[15] The oldest generic brand in continuous use, known in India since the Vedic period (c. 1100 BCE to 500 BCE), is the herbal paste known as chyawanprash, consumed for its purported health benefits and attributed to a revered rishi (or seer) named Chyawan.[33] One well-documented early example of a highly developed brand is that of White Rabbit sewing needles, dating from China's Song dynasty (960 to 1127 CE).[34][35] A copper printing plate used to print posters contained a message which roughly translates as: "Jinan Liu's Fine Needle Shop: We buy high-quality steel rods and make fine-quality needles, to be ready for use at home in no time."[36] The plate also includes a trademark in the form of a 'White Rabbit", which signified good luck and was particularly relevant to women, who were the primary purchasers. Details in the image show a white rabbit crushing herbs, and text includes advice to shoppers to look for the stone white rabbit in front of the maker's shop.[37]

In ancient Rome, a commercial brand or inscription applied to objects offered for sale was known as a titulus pictus. The inscription typically specified information such as place of origin, destination, type of product and occasionally quality claims or the name of the manufacturer.[38] Roman marks or inscriptions were applied to a very wide variety of goods, including, pots, ceramics, amphorae (storage/shipping containers)[21] and on factory-produced oil-lamps.[39] Carbonized loaves of bread, found at Herculaneum, indicate that some bakers stamped their bread with the producer's name.[40] Roman glassmakers branded their works, with the name of Ennion appearing most prominently.[41]

One merchant that made good use of the titulus pictus was Umbricius Scaurus, a manufacturer of fish sauce (also known as garum) in Pompeii, c. 35 CE. Mosaic patterns in the atrium of his house feature images of amphorae bearing his personal brand and quality claims. The mosaic depicts four different amphora, one at each corner of the atrium, and bearing labels as follows:[42]

- 1. G(ari) F(los) SCO/ SCAURI/ EX OFFI/NA SCAU/RI (translated as: "The flower of garum, made of the mackerel, a product of Scaurus, from the shop of Scaurus")

- 2. LIQU/ FLOS (translated as: "The flower of Liquamen")

- 3. G F SCOM/ SCAURI (translated as: "The flower of garum, made of the mackerel, a product of Scaurus")

- 4. LIQUAMEN/ OPTIMUM/ EX OFFICI/A SCAURI (translated as: "The best liquamen, from the shop of Scaurus")

Scaurus' fish sauce was known by people across the Mediterranean to be of very high quality, and its reputation traveled as far away as modern France.[42] In both Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum, archaeological evidence also points to evidence of branding and labeling in relatively common use across a broad range of goods. Wine jars, for example, were stamped with names, such as "Lassius" and "L. Eumachius"; probably references to the name of the producer.

The use of identity marks on products declined following the fall of the Roman Empire. In the European Middle Ages, heraldry developed a language of visual symbolism which would feed into the evolution of branding,[43] and with the rise of the merchant guilds the use of marks resurfaced and was applied to specific types of goods. By the 13th century, the use of maker's marks had become evident on a broad range of goods. In 1266, makers' marks on bread became compulsory in England.[44] The Italians used brands in the form of watermarks on paper in the 13th century.[45] Blind stamps, hallmarks, and silver-makers' marks—all types of brand—became widely used across Europe during this period. Hallmarks, although known from the 4th-century, especially in Byzantium,[46] only came into general use during the Medieval period.[47] British silversmiths introduced hallmarks for silver in 1300.[48]

Some brands still in existence as of 2018[update] date from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries' period of mass-production. Bass Brewery, the British brewery founded in 1777, became a pioneer in international brand marketing. Many years before 1855, Bass applied a red triangle to casks of its pale ale. In 1876, its red-triangle brand became the first registered trademark issued by the British government.[49] Guinness World Records recognizes Tate & Lyle (of Lyle's Golden Syrup) as Britain's, and the world's, oldest branding and packaging, with its green-and-gold packaging having remained almost unchanged since 1885.[50] Twinings tea has used the same logo – capitalized font beneath a lion crest – since 1787, making it the world's oldest in continuous use.[51][52]

A characteristic feature of 19th-century mass-marketing was the widespread use of branding, originating with the advent of packaged goods.[15] Industrialization moved the production of many household items, such as soap, from local communities to centralized factories. When shipping their items, the factories would literally brand their logo or company insignia on the barrels used, effectively using a corporate trademark as a quasi-brand.[54]

Factories established following the Industrial Revolution introduced mass-produced goods and needed to sell their products to a wider market—that is, to customers previously familiar only with locally produced goods.[55] It became apparent that a generic package of soap had difficulty competing with familiar, local products. Packaged-goods manufacturers needed to convince the market that the public could place just as much trust in the non-local product. Gradually, manufacturers began using personal identifiers to differentiate their goods from generic products on the market. Marketers generally began to realize that brands, to which personalities were attached, outsold rival brands.[56] By the 1880s, large manufacturers had learned to imbue their brands' identity with personality traits such as youthfulness, fun, sex appeal, luxury or the "cool" factor. This began the modern practice now known as branding, where the consumers buy the brand instead of the product and rely on the brand name instead of a retailer's recommendation.

The process of giving a brand "human" characteristics represented, at least in part, a response to consumer concerns about mass-produced goods.[57] The Quaker Oats Company began using the image of the Quaker Man in place of a trademark from the late 1870s, with great success.[58] Pears' soap, Campbell's soup, Coca-Cola, Juicy Fruit chewing gum and Aunt Jemima pancake mix were also among the first products to be "branded" in an effort to increase the consumer's familiarity with the product's merits. Other brands which date from that era, such as Ben's Original rice and Kellogg's breakfast cereal, furnish illustrations of the trend.

By the early 1900s, trade press publications, advertising agencies, and advertising experts began producing books and pamphlets exhorting manufacturers to bypass retailers and to advertise directly to consumers with strongly branded messages. Around 1900, advertising guru James Walter Thompson published a housing advertisement explaining trademark advertising. This was an early commercial explanation of what scholars now recognize as modern branding and the beginnings of brand management.[59] This trend continued to the 1980s, and as of 2018[update] is quantified by marketers in concepts such as brand value and brand equity.[60] Naomi Klein has described this development as "brand equity mania".[61] In 1988, for example, Philip Morris Companies purchased Kraft Foods Inc. for six times what the company was worth on paper. Business analysts reported that what they really purchased was the brand name.

With the rise of mass media in the early 20th century, companies adopted techniques that allowed their messages to stand out. Slogans, mascots, and jingles began to appear on radio in the 1920s and in early television in the 1930s. Soap manufacturers sponsored many of the earliest radio drama series, and the genre became known as soap opera.[62]

By the 1940s, manufacturers began to recognize the way in which consumers had started to develop relationships with their brands in a social/psychological/anthropological sense.[63] Advertisers began to use motivational research and consumer research to gather insights into consumer purchasing. Strong branded campaigns for Chrysler and Exxon/Esso, using insights drawn from research into psychology and cultural anthropology, led to some of the most enduring campaigns of the 20th-century.[64] Brand advertisers began to imbue goods and services with a personality, based on the insight that consumers searched for brands with personalities that matched their own.[65][66]

Concepts

Effective branding, attached to strong brand values, can result in higher sales of not only one product, but of other products associated with that brand.[67] If a customer loves Pillsbury biscuits and trusts the brand, he or she is more likely to try other products offered by the company – such as chocolate-chip cookies, for example. Brand development, often performed by a design team, takes time to produce.

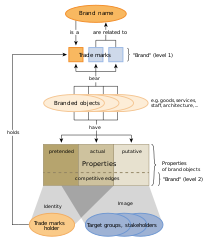

Brand names and trademarks

A brand name is the part of a brand that can be spoken or written and identifies a product, service or company and sets it apart from other comparable products within a category. A brand name may include words, phrases, signs, symbols, designs, or any combination of these elements. For consumers, a brand name is a "memory heuristic": a convenient way to remember preferred product choices. A brand name is not to be confused with a trademark which refers to the brand name or part of a brand that is legally protected.[68] For example, Coca-Cola not only protects the brand name, Coca-Cola, but also protects the distinctive Spencerian script and the contoured shape of the bottle.

Corporate brand identity

Brand identity is a collection of individual components, such as a name, a design, a set of images, a slogan, a vision, writing style, a particular font or a symbol etc. which sets the brand aside from others.[69][70] For a company to exude a strong sense of brand identity, it must have an in-depth understanding of its target market, competitors and the surrounding business environment.[9] Brand identity includes both the core identity and the extended identity.[9] The core identity reflects consistent long-term associations with the brand; whereas the extended identity involves the intricate details of the brand that help generate a constant motif.[9]

According to Kotler et al. (2009), a brand's identity may deliver four levels of meaning:

- attributes

- benefits

- values

- personality

A brand's attributes are a set of labels with which the corporation wishes to be associated. For example, a brand may showcase its primary attribute as environmental friendliness. However, a brand's attributes alone are not enough to persuade a customer into purchasing the product.[69] These attributes must be communicated through benefits, which are more emotional translations. If a brand's attribute is being environmentally friendly, customers will receive the benefit of feeling that they are helping the environment by associating with the brand. Aside from attributes and benefits, a brand's identity may also involve branding to focus on representing its core set of values.[69] If a company is seen to symbolize specific values, it will, in turn, attract customers who also believe in these values.[65] For example, Nike's brand represents the value of a "just do it" attitude.[71] Thus, this form of brand identification attracts customers who also share this same value. Even more extensive than its perceived values is a brand's personality.[69] Quite literally, one can easily describe a successful brand identity as if it were a person.[69] This form of brand identity has proven to be the most advantageous in maintaining long-lasting relationships with consumers, as it gives them a sense of personal interaction with the brand [72] Collectively, all four forms of brand identification help to deliver a powerful meaning behind what a corporation hopes to accomplish, and to explain why customers should choose one brand over its competitors.[9]

Brand personality

Brand personality refers to "the set of human personality traits that are both applicable to and relevant for brands."[73] Marketers and consumer researchers often argue that brands can be imbued with human-like characteristics which resonate with potential consumers.[74] Such personality traits can assist marketers to create unique, brands that are differentiated from rival brands. Aaker conceptualized brand personality as consisting of five broad dimensions, namely: sincerity (down-to-earth, honest, wholesome, and cheerful), excitement (daring, spirited, imaginative, and up to date), competence (reliable, intelligent, and successful), sophistication (glamorous, upper class, charming), and ruggedness (outdoorsy and tough).[75] Subsequent research studies have suggested that Aaker's dimensions of brand personality are relatively stable across different industries, market segments and over time. Much of the literature on branding suggests that consumers prefer brands with personalities that are congruent with their own.[76][77]

Consumers may distinguish the psychological aspect (brand associations like thoughts, feelings, perceptions, images, experiences, beliefs, attitudes, and so on that become linked to the brand) of a brand from the experiential aspect. The experiential aspect consists of the sum of all points of contact with the brand and is termed the consumer's brand experience. The brand is often intended to create an emotional response and recognition, leading to potential loyalty and repeat purchases. The brand experience is a brand's action perceived by a person.[78] The psychological aspect, sometimes referred to as the brand image, is a symbolic construct created within the minds of people, consisting of all the information and expectations associated with a product, with a service, or with the companies providing them.[78]

Marketers or product managers that responsible for branding, seek to develop or align the expectations behind the brand experience, creating the impression that a brand associated with a product or service has certain qualities or characteristics, which make it special or unique.[79] A brand can, therefore, become one of the most valuable elements in an advertising theme, as it demonstrates what the brand owner is able to offer in the marketplace. This means that building a strong brand helps to distinguish a product from similar ones and differentiate it from competitors.[65] The art of creating and maintaining a brand is called brand management. The orientation of an entire organization towards its brand is called brand orientation. Brand orientation develops in response to market intelligence.[79]

Careful brand management seeks to make products or services relevant and meaningful to a target audience. Marketers tend to treat brands as more than the difference between the actual cost of a product and its selling price; rather brands represent the sum of all valuable qualities of a product to the consumer and are often treated as the total investment in brand building activities including marketing communications.[80]

Consumers may look on branding as an aspect of products or services,[11] as it often serves to denote a certain attractive quality or characteristic (see also brand promise). From the perspective of brand owners, branded products or services can command higher prices. Where two products resemble each other, but one of the products has no associated branding (such as a generic, store-branded product), potential purchasers may often select the more expensive branded product on the basis of the perceived quality of the brand or on the basis of the reputation of the brand owner.

Brand awareness

Brand awareness involves a customer's ability to recall and/or recognize brands, logos, and branded advertising. Brands help customers to understand which brands or products belong to which product or service category. Brands assist customers to understand the constellation of benefits offered by individual brands, and how a given brand within a category is differentiated from its competing brands, and thus the brand helps customers & potential customers understand which brand satisfies their needs. Thus, the brand offers the customer a short-cut to understanding the different product or service offerings that make up a particular category.

Brand awareness is a key step in the customer's purchase decision process, since some kind of awareness is a precondition to purchasing. That is, customers will not consider a brand if they are not aware of it.[81] Brand awareness is a key component in understanding the effectiveness both of a brand's identity and of its communication methods.[82] Successful brands are those that consistently generate a high level of brand awareness, as this can be the pivotal factor in securing customer transactions.[83] Various forms of brand awareness can be identified. Each form reflects a different stage in a customer's cognitive ability to address the brand in a given circumstance.[11]

Marketers typically identify two distinct types of brand awareness; namely brand recall (also known as unaided recall or occasionally spontaneous recall) and brand recognition (also known as aided brand recall).[84] These types of awareness operate in entirely different ways with important implications for marketing strategy and advertising.

- Most companies aim for "Top-of-Mind" which occurs when a brand pops into a consumer's mind when asked to name brands in a product category. For example, when someone is asked to name a type of facial tissue, the common answer, "Kleenex", will represent a top-of-mind brand. Top-of-mind awareness is a special case of brand recall.

- Brand recall (also known as unaided brand awareness or spontaneous awareness) refers to the brand or set of brands that a consumer can elicit from memory when prompted with a product category

- Brand recognition (also known as aided brand awareness) occurs when consumers see or read a list of brands, and express familiarity with a particular brand only after they hear or see it as a type of memory aide.

- Strategic awareness occurs when a brand is not only top-of-mind to consumers, but also has distinctive qualities which consumers perceive as making it better than other brands in the particular market. The distinction(s) that set a product apart from the competition is/are also known as the unique selling point or USP.[85]

Brand recognition

Brand recognition is one of the initial phases of brand awareness and validates whether or not a customer remembers being pre-exposed to the brand.[83] Brand recognition (also known as aided brand recall) refers to consumers' ability to correctly differentiate a brand when they come into contact with it. This does not necessarily require that the consumers identify or recall the brand name. When customers experience brand recognition, they are triggered by either a visual or verbal cue.[11] For example, when looking to satisfy a category need such as a toilet paper, the customer would firstly be presented with multiple brands to choose from. Once the customer is visually or verbally faced with a brand, he/she may remember being introduced to the brand before. When given some type of cue, consumers who are able to retrieve the particular memory node that referred to the brand, they exhibit brand recognition.[11] Often, this form of brand awareness assists customers in choosing one brand over another when faced with a low-involvement purchasing decision.[86]

Brand recognition is often the mode of brand awareness that operates in retail shopping environments. When presented with a product at the point-of-sale, or after viewing its visual packaging, consumers are able to recognize the brand and may be able to associate it with attributes or meanings acquired through exposure to promotion or word-of-mouth referrals.[87] In contrast to brand recall, where few consumers are able to spontaneously recall brand names within a given category, when prompted with a brand name, a larger number of consumers are typically able to recognize it.

Brand recognition is most successful when people can elicit recognition without being explicitly exposed to the company's name, but rather through visual signifiers like logos, slogans, and colors.[88] For example, Disney successfully branded its particular script font (originally created for Walt Disney's "signature" logo), which it used in the logo for go.com.

Brand recall

Unlike brand recognition, brand recall (also known as unaided brand recall or spontaneous brand recall) is the ability of the customer retrieving the brand correctly from memory.[11] Rather than being given a choice of multiple brands to satisfy a need, consumers are faced with a need first, and then must recall a brand from their memory to satisfy that need. This level of brand awareness is stronger than brand recognition, as the brand must be firmly cemented in the consumer's memory to enable unassisted remembrance.[83] This gives the company huge advantage over its competitors because the customer is already willing to buy or at least know the company offering available in the market. Thus, brand recall is a confirmation that previous branding touchpoints have successfully fermented in the minds of its consumers.[86]

Marketing-mix modeling can help marketing leaders optimize how they spend marketing budgets to maximize the impact on brand awareness or on sales. Managing brands for value creation will often involve applying marketing-mix modeling techniques in conjunction with brand valuation.[69]

Brand elements

Brands typically comprise various elements, such as:[89]

- name: the word or words used to identify a company, product, service, or concept

- logo: the visual trademark that identifies a brand

- tagline or catchphrase: a short phrase always used in the product's advertising and closely associated with the brand

- graphics: the "dynamic ribbon" is a trademarked part of Coca-Cola's brand

- shapes: the distinctive shapes of the Coca-Cola bottle and of the Volkswagen Beetle are trademarked elements of those brands

- colors: the instant recognition consumers have when they see Tiffany & Co.'s robin's egg blue (Pantone No. 1837). Tiffany & Co.'s trademarked the color in 1998.[90]

- sounds: a unique tune or set of notes can denote a brand. NBC's chimes provide a famous example.

- scents: the rose-jasmine-musk scent of Chanel No. 5 is trademarked

- tastes: Kentucky Fried Chicken has trademarked its special recipe of eleven herbs and spices for fried chicken

- movements: Lamborghini has trademarked the upward motion of its car doors

Brand communication

Although brand identity is a fundamental asset to a brand's equity, the worth of a brand's identity would become obsolete without ongoing brand communication.[91] Integrated marketing communications (IMC) relates to how a brand transmits a clear consistent message to its stakeholders .[82] Five key components comprise IMC:[69]

- Advertising

- Sales promotions

- Direct marketing

- Personal selling

- Public relations

The effectiveness of a brand's communication is determined by how accurately the customer perceives the brand's intended message through its IMC. Although IMC is a broad strategic concept, the most crucial brand communication elements are pinpointed to how the brand sends a message and what touch points the brand uses to connect with its customers .[82]

One can analyze the traditional communication model into several consecutive steps:[69]

- Firstly, a source/sender wishes to convey a message to a receiver. This source must encode the intended message in a way that the receiver will potentially understand.[82]

- After the encoding stage, the forming of the message is complete and is portrayed through a selected channel.[92] In IMC, channels may include media elements such as advertising, public relations, sales promotions, etc.[82]

- It is at this point where the message can often deter from its original purpose as the message must go through the process of being decoded, which can often lead to unintended misinterpretation.[92]

- Finally, the receiver retrieves the message and attempts to understand what the sender was aiming to render. Often, a message may be incorrectly received due to noise in the market, which is caused by "…unplanned static or distortion during the communication process".[69]

- The final stage of this process is when the receiver responds to the message, which is received by the original sender as feedback.[72]

When a brand communicates a brand identity to a receiver, it runs the risk of the receiver incorrectly interpreting the message. Therefore, a brand should use appropriate communication channels to positively "…affect how the psychological and physical aspects of a brand are perceived".[93]

In order for brands to effectively communicate to customers, marketers must "…consider all touch point|s, or sources of contact, that a customer has with the brand".[94] Touch points represent the channel stage in the traditional communication model, where a message travels from the sender to the receiver. Any point where a customer has an interaction with the brand - whether watching a television advertisement, hearing about a brand through word of mouth or even noticing a branded license plate – defines a touchpoint. According to Dahlen et al. (2010), every touchpoint has the "…potential to add positive – or suppress negative – associations to the brand's equity" [93] Thus, a brand's IMC should cohesively deliver positive messages through appropriate touch points associated with its target market. One methodology involves using sensory stimuli touch points to activate customer emotion.[94] For example, if a brand consistently uses a pleasant smell as a primary touchpoint, the brand has a much higher chance of creating a positive lasting effect on its customers' senses as well as memory.[72] Another way a brand can ensure that it is utilizing the best communication channel is by focusing on touchpoints that suit particular areas associated with customer experience.[69] As suggested Figure 2, certain touch points link with a specific stage in customer-brand-involvement. For example, a brand may recognize that advertising touchpoints are most effective during the pre-purchase experience stage therefore they may target their advertisements to new customers rather than to existing customers. Overall, a brand has the ability to strengthen brand equity by using IMC branding communications through touchpoints.[94]

Brand communication is important in ensuring brand success in the business world and refers to how businesses transmit their brand messages, characteristics and attributes to their consumers.[95] One method of brand communication that companies can exploit involves electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM). eWOM is a relatively new approach [96] identified to communicate with consumers. One popular method of eWOM involves social networking sites (SNSs) such as Twitter.[97] A study found that consumers classed their relationship with a brand as closer if that brand was active on a specific social media site (Twitter). Research further found that the more consumers "retweeted" and communicated with a brand, the more they trusted the brand. This suggests that a company could look to employ a social-media campaign to gain consumer trust and loyalty as well as in the pursuit of communicating brand messages.

McKee (2014) also looked into brand communication and states that when communicating a brand, a company should look to simplify its message as this will lead to more value being portrayed as well as an increased chance of target consumers recalling and recognizing the brand.[98]

In 2012 Riefler stated that if the company communicating a brand is a global organization or has future global aims, that company should look to employ a method of communication that is globally appealing to their consumers, and subsequently choose a method of communication with will be internationally understood.[99] One way a company can do this involves choosing a product or service's brand name, as this name will need to be suitable for the marketplace that it aims to enter.[100]

It is important that if a company wishes to develop a global market, the company name will also need to be suitable in different cultures and not cause offense or be misunderstood.[101] When communicating a brand, a company needs to be aware that they must not just visually communicate their brand message and should take advantage of portraying their message through multi-sensory information.[102] One article suggests that other senses, apart from vision, need to be targeted when trying to communicate a brand with consumers.[103] For example, a jingle or background music can have a positive effect on brand recognition, purchasing behaviour and brand recall.

Therefore, when looking to communicate a brand with chosen consumers, companies should investigate a channel of communication that is most suitable for their short-term and long-term aims and should choose a method of communication that is most likely to reach their target consumers.[99] The match-up between the product, the consumer lifestyle, and the endorser is important for the effectiveness of brand communication.

Global brand variables

Brand name

The term "brand name" is quite often used interchangeably with "brand", although it is more correctly used to specifically denote written or spoken linguistic elements of any product. In this context, a "brand name" constitutes a type of trademark, if the brand name exclusively identifies the brand owner as the commercial source of products or services. A brand owner may seek to protect proprietary rights in relation to a brand name through trademark registration – such trademarks are called "Registered Trademarks". Advertising spokespersons have also become part of some brands, for example: Mr. Whipple of Charmin toilet tissue and Tony the Tiger of Kellogg's Frosted Flakes. Putting a value on a brand by brand valuation or using marketing mix modeling techniques is distinct to valuing a trademark.

Types of brand names

Brand names come in many styles.[104]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Marque

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk