A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Christianity | |

|---|---|

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem, the holiest Christian site | |

| Classification | Abrahamic |

| Scripture | Bible |

| Theology | Monotheistic |

| Region | Worldwide[1] |

| Language | Biblical Hebrew, Biblical Aramaic, Biblical Greek |

| Territory | Christendom |

| Founder | Jesus Christ |

| Origin | 1st century AD Judaea, Roman Empire |

| Separated from | Second Temple Judaism[note 1] |

| Separations | Unitarian Universalism[7] |

| Number of followers | c. 2.4 billion |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christianity (/krɪstʃiˈænɪti/ or /krɪstiˈænɪti/) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.4 billion followers, comprising around 31.2% of the world population.[8] Its adherents, known as Christians, are estimated to make up a majority of the population in 157 countries and territories. Christians believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, whose coming as the Messiah was prophesied in the Hebrew Bible (called the Old Testament in Christianity) and chronicled in the New Testament.

Christianity remains culturally diverse in its Western and Eastern branches, and doctrinally diverse concerning justification and the nature of salvation, ecclesiology, ordination, and Christology. The creeds of various Christian denominations generally hold in common Jesus as the Son of God—the Logos incarnated—who ministered, suffered, and died on a cross, but rose from the dead for the salvation of humankind; and referred to as the gospel, meaning the "good news". The four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John describe Jesus's life and teachings, with the Old Testament as the gospels' respected background.

Christianity began in the 1st century after the birth of Jesus as a Judaic sect with Hellenistic influence, in the Roman province of Judea. The disciples of Jesus spread their faith around the Eastern Mediterranean area, despite significant persecution. The inclusion of Gentiles led Christianity to slowly separate from Judaism (2nd century). Emperor Constantine I decriminalized Christianity in the Roman Empire by the Edict of Milan (313), later convening the Council of Nicaea (325) where Early Christianity was consolidated into what would become the state religion of the Roman Empire (380). The Church of the East and Oriental Orthodoxy both split over differences in Christology (5th century), while the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church separated in the East–West Schism (1054). Protestantism split into numerous denominations from the Catholic Church in the Reformation era (16th century). Following the Age of Discovery (15th–17th century), Christianity expanded throughout the world via missionary work, evangelism, immigration and extensive trade. Christianity played a prominent role in the development of Western civilization, particularly in Europe from late antiquity and the Middle Ages.[9][10][11]

The six major branches of Christianity are Roman Catholicism (1.3 billion people), Protestantism (900 million),[note 2][13][14] Eastern Orthodoxy (230 million), Oriental Orthodoxy (60 million), Restorationism (35 million),[note 3] and the Church of the East (600 thousand). Smaller church communities number in the thousands despite efforts toward unity (ecumenism). In the West, Christianity remains the dominant religion even with a decline in adherence, with about 70% of that population identifying as Christian. Christianity is growing in Africa and Asia, the world's most populous continents. Christians remain greatly persecuted in many regions of the world, particularly in the Middle East, North Africa, East Asia, and South Asia.

Etymology

Early Jewish Christians referred to themselves as 'The Way' (Koinē Greek: τῆς ὁδοῦ, romanized: tês hodoû), probably coming from Isaiah 40:3, "prepare the way of the Lord".[note 4] According to Acts 11:26, the term "Christian" (Χρῑστῐᾱνός, Khrīstiānós), meaning "followers of Christ" in reference to Jesus's disciples, was first used in the city of Antioch by the non-Jewish inhabitants there.[22] The earliest recorded use of the term "Christianity/Christianism" (Χρῑστῐᾱνισμός, Khrīstiānismós) was by Ignatius of Antioch around 100 AD.[23] The name Jesus comes from Greek: Ἰησοῦς Iēsous, likely from Hebrew/Aramaic: יֵשׁוּעַ Yēšūaʿ.

Beliefs

While Christians worldwide share basic convictions, there are differences of interpretations and opinions of the Bible and sacred traditions on which Christianity is based.[24]

Creeds

Concise doctrinal statements or confessions of religious beliefs are known as creeds. They began as baptismal formulae and were later expanded during the Christological controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries to become statements of faith. "Jesus is Lord" is the earliest creed of Christianity and continues to be used, as with the World Council of Churches.[25]

The Apostles' Creed is the most widely accepted statement of the articles of Christian faith. It is used by a number of Christian denominations for both liturgical and catechetical purposes, most visibly by liturgical churches of Western Christian tradition, including the Latin Church of the Catholic Church, Lutheranism, Anglicanism, and Western Rite Orthodoxy. It is also used by Presbyterians, Methodists, and Congregationalists.

This particular creed was developed between the 2nd and 9th centuries. Its central doctrines are those of the Trinity and God the Creator. Each of the doctrines found in this creed can be traced to statements current in the apostolic period. The creed was apparently used as a summary of Christian doctrine for baptismal candidates in the churches of Rome.[26] Its points include:

- Belief in God the Father, Jesus Christ as the Son of God, and the Holy Spirit

- The death, descent into hell, resurrection and ascension of Christ

- The holiness of the Church and the communion of saints

- Christ's second coming, the Day of Judgement and salvation of the faithful

The Nicene Creed was formulated, largely in response to Arianism, at the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople in 325 and 381 respectively,[27][28] and ratified as the universal creed of Christendom by the First Council of Ephesus in 431.[29]

The Chalcedonian Definition, or Creed of Chalcedon, developed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451,[30] though rejected by the Oriental Orthodox,[31] taught Christ "to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably": one divine and one human, and that both natures, while perfect in themselves, are nevertheless also perfectly united into one person.[32]

The Athanasian Creed, received in the Western Church as having the same status as the Nicene and Chalcedonian, says: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confounding the Persons nor dividing the Substance".[33]

Most Christians (Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Protestant alike) accept the use of creeds and subscribe to at least one of the creeds mentioned above.[34]

Certain Evangelical Protestants, though not all of them, reject creeds as definitive statements of faith, even while agreeing with some or all of the substance of the creeds. Also rejecting creeds are groups with roots in the Restoration Movement, such as the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), the Evangelical Christian Church in Canada, and the Churches of Christ.[35][36]: 14–15 [37]: 123

Jesus

The central tenet of Christianity is the belief in Jesus as the Son of God and the Messiah (Christ).[38][39] Christians believe that Jesus, as the Messiah, was anointed by God as savior of humanity and hold that Jesus's coming was the fulfillment of messianic prophecies of the Old Testament. The Christian concept of messiah differs significantly from the contemporary Jewish concept. The core Christian belief is that through belief in and acceptance of the death and resurrection of Jesus, sinful humans can be reconciled to God, and thereby are offered salvation and the promise of eternal life.[40]

While there have been many theological disputes over the nature of Jesus over the earliest centuries of Christian history, generally, Christians believe that Jesus is God incarnate and "true God and true man" (or both fully divine and fully human). Jesus, having become fully human, suffered the pains and temptations of a mortal man, but did not sin. As fully God, he rose to life again. According to the New Testament, he rose from the dead,[41] ascended to heaven, is seated at the right hand of the Father,[42] and will ultimately return[43] to fulfill the rest of the Messianic prophecy, including the resurrection of the dead, the Last Judgment, and the final establishment of the Kingdom of God.

According to the canonical gospels of Matthew and Luke, Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit and born from the Virgin Mary. Little of Jesus's childhood is recorded in the canonical gospels, although infancy gospels were popular in antiquity.[44] In comparison, his adulthood, especially the week before his death, is well documented in the gospels contained within the New Testament, because that part of his life is believed to be most important. The biblical accounts of Jesus's ministry include: his baptism, miracles, preaching, teaching, and deeds.

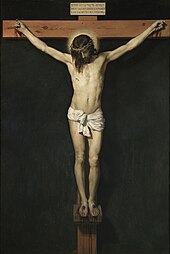

Death and resurrection

Christians consider the resurrection of Jesus to be the cornerstone of their faith (see 1 Corinthians 15) and the most important event in history.[45] Among Christian beliefs, the death and resurrection of Jesus are two core events on which much of Christian doctrine and theology is based.[46] According to the New Testament, Jesus was crucified, died a physical death, was buried within a tomb, and rose from the dead three days later.[47]

The New Testament mentions several post-resurrection appearances of Jesus on different occasions to his twelve apostles and disciples, including "more than five hundred brethren at once",[48] before Jesus's ascension to heaven. Jesus's death and resurrection are commemorated by Christians in all worship services, with special emphasis during Holy Week, which includes Good Friday and Easter Sunday.

The death and resurrection of Jesus are usually considered the most important events in Christian theology, partly because they demonstrate that Jesus has power over life and death and therefore has the authority and power to give people eternal life.[49]

Christian churches accept and teach the New Testament account of the resurrection of Jesus with very few exceptions.[50] Some modern scholars use the belief of Jesus's followers in the resurrection as a point of departure for establishing the continuity of the historical Jesus and the proclamation of the early church.[51] Some liberal Christians do not accept a literal bodily resurrection,[52][53] seeing the story as richly symbolic and spiritually nourishing myth. Arguments over death and resurrection claims occur at many religious debates and interfaith dialogues.[54] Paul the Apostle, an early Christian convert and missionary, wrote, "If Christ was not raised, then all our preaching is useless, and your trust in God is useless".[55][56]

Salvation

"For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life".

— John 3:16, NIV[57]

Paul the Apostle, like Jews and Roman pagans of his time, believed that sacrifice can bring about new kinship ties, purity, and eternal life.[58] For Paul, the necessary sacrifice was the death of Jesus: Gentiles who are "Christ's" are, like Israel, descendants of Abraham and "heirs according to the promise"[59][60] The God who raised Jesus from the dead would also give new life to the "mortal bodies" of Gentile Christians, who had become with Israel, the "children of God", and were therefore no longer "in the flesh".[61][58]

Modern Christian churches tend to be much more concerned with how humanity can be saved from a universal condition of sin and death than the question of how both Jews and Gentiles can be in God's family. According to Eastern Orthodox theology, based upon their understanding of the atonement as put forward by Irenaeus' recapitulation theory, Jesus' death is a ransom. This restores the relation with God, who is loving and reaches out to humanity, and offers the possibility of theosis c.q. divinization, becoming the kind of humans God wants humanity to be. According to Catholic doctrine, Jesus' death satisfies the wrath of God, aroused by the offense to God's honor caused by human's sinfulness. The Catholic Church teaches that salvation does not occur without faithfulness on the part of Christians; converts must live in accordance with principles of love and ordinarily must be baptized.[62] In Protestant theology, Jesus' death is regarded as a substitutionary penalty carried by Jesus, for the debt that has to be paid by humankind when it broke God's moral law.[63]

Christians differ in their views on the extent to which individuals' salvation is pre-ordained by God. Reformed theology places distinctive emphasis on grace by teaching that individuals are completely incapable of self-redemption, but that sanctifying grace is irresistible.[64] In contrast Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and Arminian Protestants believe that the exercise of free will is necessary to have faith in Jesus.[65]

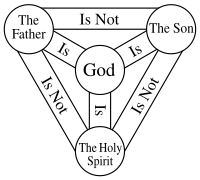

Trinity

Trinity refers to the teaching that the one God[67] comprises three distinct, eternally co-existing persons: the Father, the Son (incarnate in Jesus Christ) and the Holy Spirit. Together, these three persons are sometimes called the Godhead,[68][69][70] although there is no single term in use in Scripture to denote the unified Godhead.[71] In the words of the Athanasian Creed, an early statement of Christian belief, "the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, and yet there are not three Gods but one God".[72] They are distinct from another: the Father has no source, the Son is begotten of the Father, and the Spirit proceeds from the Father. Though distinct, the three persons cannot be divided from one another in being or in operation. While some Christians also believe that God appeared as the Father in the Old Testament, it is agreed that he appeared as the Son in the New Testament and will still continue to manifest as the Holy Spirit in the present. But still, God still existed as three persons in each of these times.[73] However, traditionally there is a belief that it was the Son who appeared in the Old Testament because, for example, when the Trinity is depicted in art, the Son typically has the distinctive appearance, a cruciform halo identifying Christ, and in depictions of the Garden of Eden, this looks forward to an Incarnation yet to occur. In some Early Christian sarcophagi, the Logos is distinguished with a beard, "which allows him to appear ancient, even pre-existent".[74]

The Trinity is an essential doctrine of mainstream Christianity. From earlier than the times of the Nicene Creed (325) Christianity advocated[75] the triune mystery-nature of God as a normative profession of faith. According to Roger E. Olson and Christopher Hall, through prayer, meditation, study and practice, the Christian community concluded "that God must exist as both a unity and trinity", codifying this in ecumenical council at the end of the 4th century.[76][77]

According to this doctrine, God is not divided in the sense that each person has a third of the whole; rather, each person is considered to be fully God (see Perichoresis). The distinction lies in their relations, the Father being unbegotten; the Son being begotten of the Father; and the Holy Spirit proceeding from the Father and (in Western Christian theology) from the Son. Regardless of this apparent difference, the three "persons" are each eternal and omnipotent. Other Christian religions including Unitarian Universalism, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Mormonism, do not share those views on the Trinity.

The Greek word trias[78][note 5] is first seen in this sense in the works of Theophilus of Antioch; his text reads: "of the Trinity, of God, and of His Word, and of His Wisdom".[82] The term may have been in use before this time; its Latin equivalent,[note 5] trinitas,[80] appears afterwards with an explicit reference to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, in Tertullian.[83][84] In the following century, the word was in general use. It is found in many passages of Origen.[85]

Trinitarianism

Trinitarianism denotes Christians who believe in the concept of the Trinity. Almost all Christian denominations and churches hold Trinitarian beliefs. Although the words "Trinity" and "Triune" do not appear in the Bible, beginning in the 3rd century theologians developed the term and concept to facilitate apprehension of the New Testament teachings of God as being Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Since that time, Christian theologians have been careful to emphasize that Trinity does not imply that there are three gods (the antitrinitarian heresy of Tritheism), nor that each hypostasis of the Trinity is one-third of an infinite God (partialism), nor that the Son and the Holy Spirit are beings created by and subordinate to the Father (Arianism). Rather, the Trinity is defined as one God in three persons.[86]

Nontrinitarianism

Nontrinitarianism (or antitrinitarianism) refers to theology that rejects the doctrine of the Trinity. Various nontrinitarian views, such as adoptionism or modalism, existed in early Christianity, leading to disputes about Christology.[87] Nontrinitarianism reappeared in the Gnosticism of the Cathars between the 11th and 13th centuries, among groups with Unitarian theology in the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century,[88] in the 18th-century Enlightenment, among Restorationist groups arising during the Second Great Awakening of the 19th century, and most recently, in Oneness Pentecostal churches.

Eschatology

The end of things, whether the end of an individual life, the end of the age, or the end of the world, broadly speaking, is Christian eschatology; the study of the destiny of humans as it is revealed in the Bible. The major issues in Christian eschatology are the Tribulation, death and the afterlife, (mainly for Evangelical groups) the Millennium and the following Rapture, the Second Coming of Jesus, Resurrection of the Dead, Heaven, (for liturgical branches) Purgatory, and Hell, the Last Judgment, the end of the world, and the New Heavens and New Earth.

Christians believe that the second coming of Christ will occur at the end of time, after a period of severe persecution (the Great Tribulation). All who have died will be resurrected bodily from the dead for the Last Judgment. Jesus will fully establish the Kingdom of God in fulfillment of scriptural prophecies.[89][90]

Death and afterlife

Most Christians believe that human beings experience divine judgment and are rewarded either with eternal life or eternal damnation. This includes the general judgement at the resurrection of the dead as well as the belief (held by Catholics,[91][92] Orthodox[93][94] and most Protestants) in a judgment particular to the individual soul upon physical death.

In the Catholic branch of Christianity, those who die in a state of grace, i.e., without any mortal sin separating them from God, but are still imperfectly purified from the effects of sin, undergo purification through the intermediate state of purgatory to achieve the holiness necessary for entrance into God's presence.[95] Those who have attained this goal are called saints (Latin sanctus, "holy").[96]

Some Christian groups, such as Seventh-day Adventists, hold to mortalism, the belief that the human soul is not naturally immortal, and is unconscious during the intermediate state between bodily death and resurrection. These Christians also hold to Annihilationism, the belief that subsequent to the final judgement, the wicked will cease to exist rather than suffer everlasting torment. Jehovah's Witnesses hold to a similar view.[97]

Practices

Depending on the specific denomination of Christianity, practices may include baptism, the Eucharist (Holy Communion or the Lord's Supper), prayer (including the Lord's Prayer), confession, confirmation, burial rites, marriage rites and the religious education of children. Most denominations have ordained clergy who lead regular communal worship services.[99]

Christian rites, rituals, and ceremonies are not celebrated in one single sacred language. Many ritualistic Christian churches make a distinction between sacred language, liturgical language and vernacular language. The three important languages in the early Christian era were: Latin, Greek and Syriac.[100][101][102]

Communal worship

Services of worship typically follow a pattern or form known as liturgy.[note 6] Justin Martyr described 2nd-century Christian liturgy in his First Apology (c. 150) to Emperor Antoninus Pius, and his description remains relevant to the basic structure of Christian liturgical worship:

And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons. And they who are well to do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succours the orphans and widows and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need.[104]

Thus, as Justin described, Christians assemble for communal worship typically on Sunday, the day of the resurrection, though other liturgical practices often occur outside this setting. Scripture readings are drawn from the Old and New Testaments, but especially the gospels.[note 7][105] Instruction is given based on these readings, in the form of a sermon or homily. There are a variety of congregational prayers, including thanksgiving, confession, and intercession, which occur throughout the service and take a variety of forms including recited, responsive, silent, or sung.[99] Psalms, hymns, worship songs, and other church music may be sung.[106][107] Services can be varied for special events like significant feast days.[108]

Nearly all forms of worship incorporate the Eucharist, which consists of a meal. It is reenacted in accordance with Jesus' instruction at the Last Supper that his followers do in remembrance of him as when he gave his disciples bread, saying, "This is my body", and gave them wine saying, "This is my blood".[109] In the early church, Christians and those yet to complete initiation would separate for the Eucharistic part of the service.[110] Some denominations such as Confessional Lutheran churches continue to practice 'closed communion'.[111] They offer communion to those who are already united in that denomination or sometimes individual church. Catholics further restrict participation to their members who are not in a state of mortal sin.[112] Many other churches, such as Anglican Communion and the Methodist Churches (such as the Free Methodist Church and United Methodist Church), practice 'open communion' since they view communion as a means to unity, rather than an end, and invite all believing Christians to participate.[113][114][115]

Sacraments or ordinances

And this food is called among us Eukharistia , of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.

In Christian belief and practice, a sacrament is a rite, instituted by Christ, that confers grace, constituting a sacred mystery. The term is derived from the Latin word sacramentum, which was used to translate the Greek word for mystery. Views concerning both which rites are sacramental, and what it means for an act to be a sacrament, vary among Christian denominations and traditions.[116]

The most conventional functional definition of a sacrament is that it is an outward sign, instituted by Christ, that conveys an inward, spiritual grace through Christ. The two most widely accepted sacraments are Baptism and the Eucharist; however, the majority of Christians also recognize five additional sacraments: Confirmation (Chrismation in the Eastern tradition), Holy Orders (or ordination), Penance (or Confession), Anointing of the Sick, and Matrimony (see Christian views on marriage).[116]

Taken together, these are the Seven Sacraments as recognized by churches in the High Church tradition—notably Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Independent Catholic, Old Catholic, some Lutherans and Anglicans. Most other denominations and traditions typically affirm only Baptism and Eucharist as sacraments, while some Protestant groups, such as the Quakers, reject sacramental theology.[116] Certain denominations of Christianity, such as Anabaptists, use the term "ordinances" to refer to rites instituted by Jesus for Christians to observe.[117] Seven ordinances have been taught in many Conservative Mennonite Anabaptist churches, which include "baptism, communion, footwashing, marriage, anointing with oil, the holy kiss, and the prayer covering".[98]

In addition to this, the Church of the East has two additional sacraments in place of the traditional sacraments of Matrimony and the Anointing of the Sick. These include Holy Leaven (Melka) and the sign of the cross.[118] The Schwarzenau Brethren Anabaptist churches, such as the Dunkard Brethren Church, observe the agape feast (lovefeast), a rite also observed by Moravian Church and Methodist Churches.[119]

-

A penitent confessing his sins in a Ukrainian Catholic church

-

Confirmation being administered in an Anglican church

-

Ordination of a priest in the Eastern Orthodox tradition

-

Service of the Sacrament of Holy Unction served on Great and Holy Wednesday

Liturgical calendar

Catholics, Eastern Christians, Lutherans, Anglicans and other traditional Protestant communities frame worship around the liturgical year.[120] The liturgical cycle divides the year into a series of seasons, each with their theological emphases, and modes of prayer, which can be signified by different ways of decorating churches, colors of paraments and vestments for clergy,[121] scriptural readings, themes for preaching and even different traditions and practices often observed personally or in the home.

Western Christian liturgical calendars are based on the cycle of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church,[121] and Eastern Christians use analogous calendars based on the cycle of their respective rites. Calendars set aside holy days, such as solemnities which commemorate an event in the life of Jesus, Mary, or the saints, and periods of fasting, such as Lent and other pious events such as memoria, or lesser festivals commemorating saints. Christian groups that do not follow a liturgical tradition often retain certain celebrations, such as Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost: these are the celebrations of Christ's birth, resurrection, and the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Church, respectively. A few denominations such as Quaker Christians make no use of a liturgical calendar.[122]

Symbols

Most Christian denominations have not generally practiced aniconism,[123] the avoidance or prohibition of devotional images, even if early Jewish Christians, invoking the Decalogue's prohibition of idolatry, avoided figures in their symbols.[124]

The cross, today one of the most widely recognized symbols, was used by Christians from the earliest times.[125][126] Tertullian, in his book De Corona, tells how it was already a tradition for Christians to trace the sign of the cross on their foreheads.[127] Although the cross was known to the early Christians, the crucifix did not appear in use until the 5th century.[128]

Among the earliest Christian symbols, that of the fish or Ichthys seems to have ranked first in importance, as seen on monumental sources such as tombs from the first decades of the 2nd century.[129] Its popularity seemingly arose from the Greek word ichthys (fish) forming an acrostic for the Greek phrase Iesous Christos Theou Yios Soter (Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ),[note 8] (Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior), a concise summary of Christian faith.[129]

Other major Christian symbols include the chi-rho monogram, the dove and olive branch (symbolic of the Holy Spirit), the sacrificial lamb (representing Christ's sacrifice), the vine (symbolizing the connection of the Christian with Christ) and many others. These all derive from passages of the New Testament.[128]

Baptism

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Christian_religionText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk