A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2015) |

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

|

Tunnel warfare is using tunnels and other underground cavities in war. It often includes the construction of underground facilities in order to attack or defend, and the use of existing natural caves and artificial underground facilities for military purposes. Tunnels can be used to undermine fortifications and slip into enemy territory for a surprise attack, while it can strengthen a defense by creating the possibility of ambush, counterattack and the ability to transfer troops from one portion of the battleground to another unseen and protected. Also, tunnels can serve as shelter from enemy attack.

Since antiquity, sappers have used mining against walled cites, fortresses, castles or other strongly held and fortified military positions. Defenders have dug counter-mines to attack miners or destroy a mine threatening their fortifications. Since tunnels are commonplace in urban areas, tunnel warfare is often a feature, though usually a minor one, of urban warfare. A good example of this was seen in the Syrian Civil War in Aleppo, where in March 2015 rebels planted a large amount of explosives under the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Directorate headquarters.

Tunnels are narrow and restrict fields of fire; thus, troops in a tunnel usually have only a few areas exposed to fire or sight at any one time. They can be part of an extensive labyrinth and have culs-de-sac and reduced lighting, typically creating a closed-in night combat environment.

Pre-Gunpowder

Antiquity

Ancient Greece

The Greek historian Polybius, in his Histories, gives a graphic account of mining and counter mining at the Roman siege of Ambracia:

The Aetolians ... offered a gallant resistance to the assault of the siege artillery and , therefore, in despair had recourse to mines and tunnels. Having safely secured the central one of their three works, and carefully concealed the shaft with wattle screens, they erected in front of it a covered walk or stoa about two hundred feet long, parallel with the wall; and beginning digging from that, they carried it on unceasingly day and night, working in relays. For a considerable number of days the besieged did not discover them carrying the earth away through the shaft; but when the heap of earth thus brought out became too high to be concealed from those inside the city, the commanders of the besieged garrison set to work vigorously digging a trench inside, parallel to the wall and to the stoa which faced the towers. When the trench was made to the required depth, they next placed in a row along the side of the trench nearest the wall a number of brazen vessels made very thin; and, as they walked along the bottom of the trench past these, they listened for the noise of the digging outside. Having marked the spot indicated by any of these brazen vessels, which were extraordinarily sensitive and vibrated to the sound outside, they began digging from within, at right angles to the trench, another tunnel leading under the wall, so calculated as to exactly hit the enemy's tunnel. This was soon accomplished, for the Romans had not only brought their mine up to the wall, but had under-pinned a considerable length of it on either side of their mine; and thus the two parties found themselves face to face.[1]

The Aetolians then countered the Roman mine with smoke from burning feathers with charcoal.[1] - In essence an early form of chemical warfare.

Another extraordinary use of siege-mining in ancient Greece was during Philip V of Macedon's siege of the little town of Prinassos, according to Polybius, "the ground around the town were extremely rocky and hard, making any siege-mining virtually impossible. However, Philip ordered his soldiers during the cover of night collect earth from elsewhere and throw it all down at the fake tunnel's entrance, making it look like the Macedonians were almost finished completing the tunnels. Eventually, when Philip V announced that large parts of the town-walls were undermined, the citizens surrendered without delay."[2]

Polybius also describes the Seleucids and Parthians employing tunnels and counter-tunnels during the siege of Sirynx.[3]

Roman

The oldest known sources about employing tunnels and trenches for guerrilla-like warfare are Roman. After the Revolt of the Batavi, the insurgent tribes soon started to change defensive practices, from only local strongholds to using the advantage of wider terrain. Hidden trenches to assemble for surprise attacks were dug, connected via tunnels for secure fallback.[4] In action, often barriers were used to prevent the enemy from pursuing.

Roman legions entering the country soon learned to fear this warfare, as the ambushing of marching columns caused high casualties. Therefore, they approached possibly fortified areas very carefully, giving time to evaluate, assemble troops and organize them. When the Romans were themselves on the defensive the large underground aqueduct system was used in the defense of Rome, as well as to evacuate fleeing leaders.

The use of tunnels as a means of guerrilla-like warfare against the Roman Empire was also a common practice of the Jewish rebels in Judea during the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 AD). With time the Romans understood that efforts should be made to expose these tunnels. Once an entrance was discovered fire was lit, either smoking out the rebels or suffocating them to death.

Well-preserved evidence of mining and counter-mining operations has been unearthed at the fortress of Dura-Europos, which fell to the Sassanians in 256/7 AD during Roman–Persian wars.

China

Mining was a siege method used in ancient China from at least the Warring States (481–221 BC) period forward. When enemies attempted to dig tunnels under walls for mining or entry into the city, the defenders used large bellows to pump smoke into the tunnels in order to suffocate the intruders.[5]

Post-classical

In warfare during the Middle Ages, a "mine" was a tunnel dug to bring down castles and other fortifications. Attackers used this technique when the fortification was not built on solid rock, developing it as a response to stone-built castles that could not be burned like earlier-style wooden forts. A tunnel would be excavated under the outer defenses either to provide access into the fortification or to collapse the walls. These tunnels would normally be supported by temporary wooden props as the digging progressed. Once the excavation was complete, the attackers would collapse the wall or tower being undermined by filling the excavation with combustible material that, when lit, would burn away the props leaving the structure above unsupported and thus liable to collapse.

A tactic related to mining is sapping the wall, where engineers would dig at the base of a wall with crowbars and picks. Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay recounts how at the battle of Carcassonne, during the Albigensian Crusade, "after the top of the wall had been somewhat weakened by bombardment from petraries, our engineers succeeded with great difficulty in bringing a four-wheeled wagon, covered in oxhides, close to the wall, from which they set to work to sap the wall".[6]

As in the siege of Carcassonne, defenders worked to prevent sapping by dumping anything they had down on attackers who tried to dig under the wall. Successful sapping usually ended the battle, since the defenders would no longer be able to defend their position and would surrender, or the attackers could enter the fortification and engage the defenders in close combat.

Several methods resisted or countered undermining. Often the siting of a castle could make mining difficult. The walls of a castle could be constructed either on solid rock or on sandy or water-logged land, making it difficult to dig mines. A very deep ditch or moat could be constructed in front of the walls, as was done at Pembroke Castle, or even artificial lakes, as was done at Kenilworth Castle. This makes it more difficult to dig a mine, and even if a breach is made, the ditch or moat makes exploiting the breach difficult.

Defenders could also dig counter mines. From these they could then dig into the attackers' tunnels and sortie into them to either kill the miners or to set fire to the pit-props to collapse the attackers' tunnel. Alternatively they could under-mine the attackers' tunnels and create a camouflet to collapse the attackers' tunnels. Finally if the walls were breached, they could either place obstacles in the breach, for example a cheval de frise to hinder a forlorn hope, or construct a coupure. The great concentric ringed fortresses, like Beaumaris Castle on Anglesey, were designed so that the inner walls were ready-built coupures: if an attacker succeeded in breaching the outer walls, he would enter a killing field between the lower outer walls and the higher inner walls.

Coming of gunpowder

A major change took place in the art of tunnel warfare in the 15th century in Italy with the development of gunpowder, since its use reduced the effort required to undermine a wall while also increasing lethality.

Ivan the Terrible took Kazan with the use of gunpowder explosions to undermine its walls.

Many fortresses built counter mine galleries, "hearing tunnels" which were used to listen for enemy mines being built. At a distance of about fifty yards they could be used to detect tunneling. The Kremlin had such tunnels.

Since the 16th century during assault on enemy positions saps, began to be used.

The Austrian general of Italian origin Raimondo Montecuccoli (1609–1680) in his classic work on military affairs described methods of destruction and countering of enemy saps. In his paper on "the assaulting of fortresses" Vauban (1633–1707) the creator of the French School of Fortification gave a theory of mine attack and how to calculate various saps and the amount of gunpowder needed for explosions.

19th century

Crimean War

As early as 1840 Eduard Totleben and Schilder-Schuldner had been engaged on questions of organisation and conduct of underground attacks. They began to use electric current to disrupt charges. Special boring instruments of complex design were developed.

In the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855) underground fighting became immense. At first the allies began digging saps without any precautions. After a series of explosions caused by counter mine action the allies increased the depth of the tunnels but began to meet rocky ground and the underground war had to return to higher levels. During the siege Russian sappers dug 6.8 kilometres (4.2 mi) of saps and counter mines. During the same period the allies dug 1.3 kilometres (0.81 mi). The Russians expended 12 tons of gunpowder in the underground war while the allies used 64 tons. These figures show that the Russians tried to create a more extensive network of tunnels and carried out better targeted attacks with only minimal use of gunpowder. The allies used outdated fuses so that many charges failed to go off. Conditions in the tunnels were severe: wax candles often went out, sappers fainted due to stale air, ground water flooded tunnels and counter mines. The Russians repulsed the siege and started to dig tunnels under the allies fortifications. The Russian success in the underground war was recognised by the allies. The Times noted that the laurels for this kind of warfare must go to the Russians.

American Civil War

In 1864, during the Siege of Petersburg by the Union Army of the Potomac, a mine made of 3,600 kilograms (8,000 lb) of gunpowder was set off approximately 6 metres (20 ft) under Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside's IX Corps sector. The explosion blew a gap in the Confederate defenses of Petersburg, Virginia, creating a crater 52 metres (170 ft) long, 30 to 37 metres (100 to 120 ft) wide, and at least 9 metres (30 ft) deep. The combat was accordingly known as the Battle of the Crater. From this propitious beginning, everything deteriorated rapidly for the Union attackers. Unit after unit charged into and around the crater, where soldiers milled in confusion. The Confederates quickly recovered and launched several counterattacks led by Brig. Gen. William Mahone. The breach was sealed off, and Union forces were repulsed with severe casualties. The horror of this engagement was portrayed in the Charles Frazier novel, and subsequent Anthony Minghella movie, Cold Mountain.

During the Siege of Vicksburg, in 1863, Union troops led by General Ulysses S. Grant tunnelled under the Confederate trenches and detonated a mine beneath the 3rd Louisiana Redan on June 25, 1863. The subsequent assault, led by General John A. Logan, gained a foothold in the Confederate trenches where the crater was formed, but the attackers were eventually forced to withdraw.

Modern warfare

The increased firepower that came with the use of smokeless powder, cordite and dynamite by the end of the 19th century made it very expensive to build above-ground fortifications that could withstand any attack. As a result, fortifications were covered with earth and eventually were built entirely underground to maximize protection. For the purpose of firing artillery and machine guns, emplacements had loopholes.

World War I

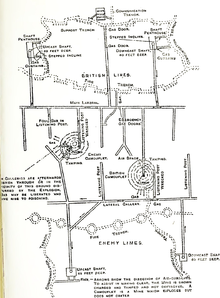

Mining saw a particular resurgence as a military tactic during the First World War, when army engineers attempted to break the stalemate of trench warfare by tunneling under no man's land and laying large quantities of explosives beneath the enemy's trenches. As in siege warfare, tunnel warfare was possible due to the static nature of the fighting.

On the Western and Italian Front during the First World War, the military employed specialist miners to dig tunnels.

On the Italian Front, the high peaks of the Dolomites range were an area of fierce mountain warfare and mining operations. In order to protect their soldiers from enemy fire and the hostile alpine environment, both Austro-Hungarian and Italian military engineers constructed fighting tunnels which offered a degree of cover and allowed better logistics support. In addition to building underground shelters and covered supply routes for their soldiers, both sides also attempted to break the stalemate of trench warfare by tunneling under no man's land and placing explosive charges beneath the enemy's positions. Their efforts in high mountain peaks such as Col di Lana, Lagazuoi and Marmolada were portrayed in fiction in Luis Trenker's Mountains on Fire film of 1931.

On the Western Front, the main objective of tunnel warfare was to place large quantities of explosives beneath enemy defensive positions. When it was detonated, the explosion would destroy that section of the trench. The infantry would then advance towards the enemy front-line hoping to take advantage of the confusion that followed the explosion of an underground mine. It could take as long as a year to dig a tunnel and place a mine. As well as digging their own tunnels, the military engineers had to listen out for enemy tunnellers. On occasions miners accidentally dug into the opposing side's tunnel and an underground fight took place. When an enemy's tunnel was found it was usually destroyed by placing an explosive charge inside.

During the height of the underground war on the Western Front in June 1916, British tunnellers fired 101 mines or camouflets, while German tunnellers fired 126 mines or camouflets. This amounts to a total of 227 mine explosions in one month – one detonation every three hours.[7] Large battles, like the Battle of the Somme in 1916 (see mines on the Somme) and the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917, were also supported by mine explosions.

Well known examples are the mines on the Italian Front laid by Austro-Hungarian and Italian miners, where the largest individual mine contained a charge of 110,000 pounds (50,000 kg) of blasting gelatin, and the activities of the Tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers on the Western Front. At the beginning of the Somme offensive, the British simultaneously detonated 19 mines of varying sizes beneath the German positions, including two mines that contained 18,000 kilograms (40,000 lb) of explosives.

In January 1917, General Plumer gave orders for over 20 mines to be placed under German lines at Messines. Over the next five months more than 8,000 m (26,000 ft) of tunnel were dug and 450–600 tons of explosive were placed in position. Simultaneous explosion of the mines took place at 3:10 a.m. on 7 June 1917. The blast killed an estimated 10,000 soldiers and was so loud it was heard in London.[8] The near simultaneous explosions created 19 large craters and ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. Two mines were not ignited in 1917 because they had been abandoned before the battle, and four were outside the area of the offensive. On 17 July 1955, a lightning strike set off one of these four latter mines. There were no human casualties, but one cow was killed. Another of the unused mines is believed to have been found in a location beneath a farmhouse,[9] but no attempt has been made to remove it.[10] The last mine fired by the British in World War I was near Givenchy on 10 August 1917,[11] after which the tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers concentrated on constructing deep dugouts for troop accommodation.

The largest single mines at Messines were at St Eloi, which was charged with 43,400 kilograms (95,600 lb) of ammonal, at Maedelstede Farm, which was charged with 43,000 kg (94,000 lb), and beneath German lines at Spanbroekmolen, which was charged with 41,000 kg (91,000 lb) of ammonal. The Spanbroekmolen mine created a crater that afterwards measured 130 metres (430 ft) from rim to rim. Now known as the Pool of Peace, it is large enough to house a 12 m (40 ft) deep lake.[12]

-

Access to German counter-mining shaft – Bayernwald trenches, Croonaert Wood, Ypres Salient

-

Mine craters – Butte de Vauquois memorial site, Vauquois, France

-

German trench destroyed by the explosion of a mine in the Battle of Messines. Approximately 10,000 German troops were killed when the mines were simultaneously detonated at 3:10 a.m. on 7 June 1917.

| Country | Region | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | West Flanders | Ypres: Hooge | area of sustained fighting between British and German tunneling units 1915–1917; see Hooge in World War I |

| Ypres: Hill 60 | area of sustained fighting between British and German tunneling units 1915–1917; also see Mines in the Battle of Messines (1917) | ||

| Ypres: St Eloi | area of sustained fighting between British and German tunneling units 1915–1917; also see The Bluff and Mines in the Battle of Messines (1917) | ||

| Heuvelland: Wytschaete | fighting between British and German tunneling units, mainly in connection with the Mines in the Battle of Messines (1917) | ||

| Messines Ridge | area of sustained fighting between British and German tunneling units, also see Mines in the Battle of Messines (1917) | ||

| France | Nord | Armentières | area of sustained fighting between British and German tunneling units |

| Aubers Ridge | fighting between British and German tunneling units, mainly in connection with the Battle of Aubers Ridge | ||

| Pas-de-Calais | Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée | area of sustained fighting between British and German tunneling units, area where William Hackett VC was killed | |

| Cuinchy | fighting between British and German tunneling units | ||

| Loos-en-Gohelle | area of sustained fighting between British and German tunneling units | ||

| Givenchy-en-Gohelle | area of sustained fighting between British and German tunneling units, also in connection with the Battle of Vimy Ridge (1917) | ||

| Vimy Ridge | Between October 1915 and April 1917 an estimated 150 French, British and German charges were fired in this 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) sector of the Western Front.[14] British tunnellers took over progressively from the French between February and May 1916. After September 1916, when the Royal Engineers had constructed defensive galleries along most of the front line, offensive mining largely ceased[14] although activities continued through the Battle of Vimy Ridge (1917). The British gallery network beneath Vimy Ridge grew to a length of 12 kilometres (7.5 mi).[14] Before the Battle of Vimy Ridge, the British tunnelling companies secretly laid a series of explosive charges under German positions in an effort to destroy surface fortifications before the assault.[15] The original plan had called for 17 mines and 9 Wombat charges to support the infantry attack, of which 13 (possibly 14) mines and 8 Wombat charges were eventually laid.[14] | ||

| Arras | fighting between British and German tunneling units, mainly in connection with the Battle of Arras (1917); also see Carrière Wellington | ||

| Somme | Beaumont-Hamel: Hawthorn Ridge | fighting between British and German tunneling units, mainly in connection with the Battle of the Somme (1916); for details, see Mines on the first day of the Somme | |

| La Boisselle | area of sustained fighting between British and German tunneling units, major sites of underground warfare were Schwabenhöhe/Lochnagar, the Y Sap mine and the L'îlot/Granathof/Glory Hole site; for details, see Mines on the first day of the Somme | ||

| Fricourt | fighting between British and German tunneling units, mainly in connection with the Battle of the Somme (1916); for details, see Mines on the first day of the Somme | ||

| Mametz | fighting between British and German tunneling units, mainly in connection with the Battle of the Somme (1916); for details, see Mines on the first day of the Somme | ||

| Dompierre | fighting between French and German tunneling units | ||

| Oise | Tracy-le-Val: Bois St Mard | fighting between French and German tunneling units | |

| Aisne | Berry-au-Bac | fighting between French and German tunneling units | |

| Marne | Perthes-lès-Hurlus | fighting between French and German tunneling units

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Tunnel_warfare Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk |