A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

Responsibility for the Holocaust is the subject of an ongoing historical debate that has spanned several decades. The debate about the origins of the Holocaust is known as functionalism versus intentionalism. Intentionalists such as Lucy Dawidowicz argue that Adolf Hitler planned the extermination of the Jewish people as early as 1918 and personally oversaw its execution. However, functionalists such as Raul Hilberg argue that the extermination plans evolved in stages, as a result of initiatives that were taken by bureaucrats in response to other policy failures. To a large degree, the debate has been settled by acknowledgement of both centralized planning and decentralized attitudes and choices.

The primary responsibility for the Holocaust rests on Hitler and the Nazi Party's leadership, but operations to persecute Jews, Romani people, homosexuals and others were also perpetrated by the Schutzstaffel (SS), the Wehrmacht, and ordinary German citizens as well as by collaborationist members of various European governments, including soldiers and civilians. A host of factors contributed to the environment in which atrocities were committed across the continent, ranging from general racism (including antisemitism), religious hatred, blind obedience, apathy, political opportunism, coercion, profiteering, and xenophobia.

Historical and philosophical interpretations

The enormity of the Holocaust has prompted much analysis. The Holocaust has been characterized as a project of industrial extermination.[1] This led authors such as Enzo Traverso to argue in The Origins of Nazi Violence that Auschwitz was explicitly a product of Western civilization originating from medieval religious and racial persecution that brought together a "particular kind of stigmatization...rethought in the light of colonial wars and genocides."[2][a] Beginning his book with a description of the guillotine, which according to him marks the entry of the Industrial Revolution into capital punishment, he writes: "Through an irony of history, the theories of Frederick Taylor" (taylorism) were applied by a totalitarian system to serve "not production, but extermination."[3][b]

Others like Russell Jacoby contend that the Holocaust is a product of German history with deep roots in German society which range from, "German authoritarianism, feeble liberalism, brash nationalism or virulent antisemitism. From A. J. P. Taylor's The Course of German History fifty-five years ago to Daniel Goldhagen's controversial work, Hitler's Willing Executioners, Nazism is understood as the outcome of a long history of uniquely German traits".[4] While some claim that the specificity of the Holocaust was also rooted in the constant antisemitism from which Jews had been the target since the foundation of Christianity, intellectual historian George Mosse argued that the extreme form of European racism that led to the Holocaust fully emerged in the eighteenth century.[5] Others argue that pseudo-scientific racist theories were elaborated upon in order to justify white supremacy and they were accompanied by the Darwinian belief in the survival of the fittest and eugenic notions of racial hygiene—particularly within the German scientific community.[6][c][d]

Authorization

The question of overall responsibility for the atrocities committed under the Nazi regime traverses the oligarchy of those in command, foremost among them Adolf Hitler. In October 1939, he authorized the first Nazi mass killing for those labeled "undesirables" in the T-4 Euthanasia Program.[7][8] The Nazis termed such people as being "Lives unworthy of life." or lebensunwertes Leben in German.[9] Before the euthanasia program in Germany-proper was over, the Nazis killed between 65,000–70,000 persons.[10] Historian Henry Friedlander calls this period during which the 70,000 adults were killed, the "first phase" of the T4 Program since the program and its contributors precipitated the Holocaust.[11] Sometime between late June 1940 when planning for Operation Barbarossa first started and March 1941, orders were approved by Hitler for the re-establishment of the Einsatzgruppen (the surviving historical record does not permit firm conclusions to be drawn about the precise date).[12] Hitler encouraged the killings of the Jews of Eastern Europe by the Einsatzgruppen death squads in a speech of July 1941.[13] Evidence suggests that in the fall of 1941, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler and Hitler agreed in principle on the complete mass extermination of the Jews of Europe by gassing, with Hitler explicitly ordering the "annihilation of the Jews" in a speech on 12 December 1941, by which time the Jewish populations in the Baltic states had been effectively eliminated.[14] To make for smoother intra-governmental cooperation in the implementation of this so-called "Final Solution to the Jewish Question", the Wannsee conference was held near Berlin on 20 January 1942, with the participation of fifteen senior officials, led by Reinhard Heydrich and Adolf Eichmann; the records of which provide the best evidence of the central planning of the Holocaust. Just five weeks later on 22 February, Hitler was recorded saying to his closest associates: "We shall regain our health only by eliminating the Jew."[15]

Allied knowledge of the atrocities

Upwards of 300 Jewish organizations attempted to provide information to U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt about the persecution of Jews in Europe, but the ethnic and cultural diversity of American immigrant Jewish communities and their comparative lack of political power in the U.S. hindered their ability to influence policy.[16] Various strategies, such as ransoming Jews following the Anschluss of 1938, failed for a host of reasons, not to exclude the unwillingness and inability of Jewish communities in the U.S. to extend financial aid to their suffering brethren.[17] Clear evidence exists that Winston Churchill was privy to intelligence reports derived from decoded German transmissions in August 1941, during which he stated:

Whole districts are being exterminated. Scores of thousands – literally scores of thousands – of executions in cold blood are being perpetrated by the German police-troops upon the Russian patriots who defend their native soil. Since the Mongol invasions of Europe in the sixteenth century, there has never been methodical, merciless butchery on such a scale, or approaching such a scale.

— Winston Churchill, 24 August 1941.[18]

During the early years of the war, the Polish government-in-exile published documents and organised meetings to spread the word about the fate of Jews (see Witold Pilecki's Report). In the summer of 1942, a Jewish labor organization (the Bund) leader, Leon Feiner got word to London that 700,000 Polish Jews had already been murdered. The Daily Telegraph published it on 25 June 1942,[19] and the BBC took the story seriously, though the U.S. State Department doubted it.[20]

On 10 August 1942, the Riegner Telegram to New York described the Nazi plan to murder all the Jews in the occupied states by deporting them to concentration camps in the east, to be exterminated in one blow, possibly by prussic acid, starting at autumn 1942. It was released in the United States by Stephen Wise of the World Jewish Congress in November 1942 after a long wait for permission from the government.[21] This led to attempts by Jewish organizations to put President Roosevelt under pressure to act on behalf of the European Jews, many of whom had tried in vain to enter either Britain or the U.S.[22]

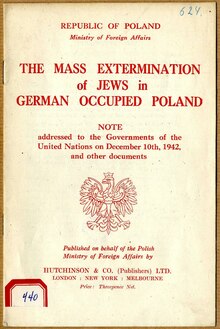

Reports were also coming into Palestine about the German atrocities during the autumn of 1942.[23] The allies received a detailed eyewitness account from Polish resistance fighter and later Georgetown University professor, Jan Karski. On 10 December 1942, the Polish government-in-exile published a 16-page report addressed to the Allied governments, titled The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland.[e]

On 17 December 1942, as the answer to Raczyński's Note, the Allies issued the Joint Declaration by Members of the United Nations, a formal declaration confirming and condemning Nazi extermination policy toward the Jews and describing the ongoing events of the Holocaust in Nazi-occupied Europe.[24] The statement was read to British House of Commons in a floor speech by Foreign secretary Anthony Eden.[25]

The death camps were discussed between American and British officials at the Bermuda Conference in April 1943.[26] On 12 May 1943, Polish government-in-exile member and Bund leader Szmul Zygielbojm committed suicide in London to protest the inaction of the world with regard to the Holocaust,[27] stating in part in his suicide letter:

I cannot continue to live and to be silent while the remnants of Polish Jewry, whose representative I am, are being killed. My comrades in the Warsaw ghetto fell with arms in their hands in the last heroic battle. I was not permitted to fall like them, together with them, but I belong with them, to their mass grave. By my death, I wish to give expression to my most profound protest against the inaction in which the world watches and permits the destruction of the Jewish people.[28]

The large camps near Auschwitz were finally surveyed by plane in April 1944. While all important German cities and production centers were bombed by Allied forces until the end of the war, no attempt was made to interdict the system of mass annihilation by destroying pertinent structures or train tracks, even though Churchill was a proponent of bombing parts of the Auschwitz complex. The US State Department was aware of the use and the location of the gas chambers of extermination camps but refused to bomb them. Significant debate continues among historians about the decision.[29][f] Throughout and after the war, the British government pressed leaders of European nations to prevent illegal Jewish immigration into Palestine and sent ships to block the sea-route to Palestine, turning back many Jewish refugees found attempting to illegally enter the region.[30]

German people

The debate on how much average Germans knew about the Holocaust continues. Robert Gellately, a historian at Oxford University, conducted a widely respected survey of the German media both before and during the war and concluded that there was a substantial amount of participation and consent in various aspects of the Holocaust from large numbers of ordinary Germans; he also concluded that German civilians frequently saw columns of slave laborers and that the basics of the concentration camps and even extermination camps, were widely known.[31] The German scholar, Peter Longerich, in a study looking at what Germans knew about the mass murders concluded that: "General information concerning the mass murder of Jews was widespread in the German population."[32] Longerich estimates that before the war ended, 32 to 40 percent of the population had knowledge about mass killings (not necessarily the extermination camps).[33]

British historian Nicholas Stargardt presents evidence of widespread public knowledge, agreement, and collusion concerning the destruction of European Jewry, the insane, feeble, disabled, Poles, Roma, and other nationals.[34] His evidence includes speeches by Nazi leaders,[35] which were broadcast or heard by a wide audience that included mention or inferences related to destroying the Jews, along with letters written between soldiers and their families describing the slaughter.[36] Historian Claudia Koonz relates how reports from the Nazi security service (SD) described the public opinion as favorable where it concerned the killing of Jews.[37] Using these same SD reports from the war years, along with a great many memoirs, diaries, and other descriptive material, historian Lawrence D. Stokes concluded that much, although not all, of the terror inflicted on the Jewish people was generally understood in the German public. Marlis Steinert came to an opposite conclusion through her own studies, contending that only a few were aware of the immense scale of the atrocities.[38] French historian, Christian Ingrao, reminds readers that one must take into consideration the possible extent to which SD reports were manipulated by the Nazi propaganda machine when reviewing them.[39] Historian Helmut Walser Smith remarks of the German people: "They were hardly indifferent to it; the responses range from outrage to affirmation to worry, especially toward the end of the war, when anxiety about accountability increased. That their imagination did not press to the particulars is not astounding. Nor is it astounding that few failed to imagine Auschwitz. The idea that not the killers go to the Jews, but the Jews are delivered up to industrial killing centers—this, in fact, was without historical precedent."[40]

Historian Eric A. Johnson and sociologist Karl-Heinz Reuband conducted interviews with more than 3,000 Germans and 500 German Jews about daily life in the Third Reich. From the Jewish questionnaires, the authors found that German society was not nearly as rife with antisemitism as one might have believed, but this dramatically changed after Hitler's ascension to power.[41] German Jews claimed that they knew of the Holocaust from a wide range of sources, which included radio broadcasts from Italy and what they heard from friends or acquaintances, but they did not know details until 1943.[42] Responses from non-Jewish Germans indicate that "the majority of Germans identified with the Nazi regime."[43] Contrary to many other accounts and/or historical interpretations, which portray rule under the Nazis as terrifying for German citizens, most of the German respondents who participated in the interviews stated that they never really feared arrest from the Gestapo.[43][g] Concerning the mass murder of the Jews, the survey results were contingent to some degree on geography, but roughly 27–29% of Germans had information about the Holocaust at some point before the war's end, and another 10–13% suspected something terrible was happening all along. Based on this information, Johnson and Reuband surmise that one-in-three Germans either heard or knew that the Holocaust was taking place before the end of the war from sources that included family members, friends, neighbors or professional colleagues.[45] Johnson suggests (in disagreement with his co-author) that it is more likely that about 50% of the German population were aware of the atrocities being committed against the Jewish people and other enemies identified by the Nazi regime.[46]

During the years 1945 through 1949, polls indicated that a majority of Germans felt that Nazism was a "good idea, badly applied". In a poll conducted in the American German occupation zone, 37% replied that 'the extermination of the Jews and Poles and other non-Aryans was necessary for the security of Germans'.[47][h] Sarah Ann Gordon in Hitler, Germans, and the Jewish Question notes that the surveys are very difficult to draw conclusions from as respondents were given only three options from which to choose: (1) Hitler was right in his treatment of the Jews, to which 0% agreed; (2) Hitler went too far in his treatment of the Jews, but something had to be done to keep them in bounds - 19% agreed; and (3) The actions against the Jews were in no way justified - 77% agreed. She also noted that another revealing example emerges from the question of whether an Aryan who marries a Jew should be condemned, a question to which 91% of the respondents answered "No". To the question: "All those who ordered the murder of civilians or participated in the murders should be made to stand trial", 94% responded "Yes".[48] Historian Tony Judt highlights how denazification and the subsequent fear of retribution from the Allies likely obscured justice due to some of the perpetrators and camouflaged underlying societal truths.[49]

Public recollection from Germans about the atrocities was also "marginalized by postwar reconstruction and diplomacy" according to historian Nicholas Wachsmann; a delay, which obscured the complexities of understanding both the Holocaust and the concentration camps that aided its facilitation.[50] Wachsmann notes how the German people often claimed that the crimes occurred behind their backs and were perpetrated by Nazi fanatics, or that they frequently dodged responsibility by equating their suffering with that of the prisoners, avowing they too had been victimized by the National Socialist regime.[51] Initially the memory of the Holocaust was repressed and set aside, but eventually, the young Federal Republic of Germany commenced its own investigations and trials.[52] Political pressure on the prosecutors and judges tempered any extensive probes and very few systematic investigations in the first decade after the war took place.[53] Later research efforts in Germany revealed that there were a "myriad" of links between the wider population and the SS camps.[54] In Austria—once part of the Greater German Reich of the Nazis—the situation was much different, as they conveniently evaded accountability through the trope of being the Nazis' first foreign victim.[55]

Implementation

During the perpetration of the Holocaust, participants came from all over Europe but the impetus for the pogroms was provided by German and Austrian Nazis. According to Holocaust historian, Raul Hilberg, the "anti-Jewish work" of the regime was "carried out in the civil service, the military, business, and the party" where "every specialization was utilized" and "every stratum of society was represented in the envelopment of the victims."[56] Sobibor death camp guard Werner Dubois stated:

I am clear about the fact that annihilation camps were used for murder. What I did was aiding in murder. If I should be sentenced, I would consider that correct. Murder is murder. In weighing the guilt, one should not in my opinion consider the specific function in the camp. Wherever we were posted there: we were all equally guilty. The camp functioned in a chain of functions. If only one element in that chain is missing, the entire enterprise comes to a stop.[57]

In an entry in the Friedrich Kellner diary, "My Opposition", dated 28 October 1941, the German justice inspector recorded a conversation he had in Laubach with a German soldier who had witnessed a massacre in Poland.[58][i] French officials at the Parisian branch of the Barclays Bank volunteered the names of their Jewish employees to Nazi authorities, and many of them ended up in the death camps.[59] An insightful perspective is provided by Konnilyn G. Feig, who wrote:

Hitler exterminated the Jews of Europe. But he did not do so alone. The task was so enormous, complex, time-consuming, and mentally and economically demanding that it took the best efforts of millions of Germans... All spheres of life in Germany actively participated: Businessmen, policemen, bankers, doctors, lawyers, soldiers, railroad and factory workers, chemists, pharmacists, foremen, production managers, economists, manufacturers, jewelers, diplomats, civil servants, propagandists, film makers and film stars, professors, teachers, politicians, mayors, party members, construction experts, art dealers, architects, landlords, janitors, truck drivers, clerks, industrialists, scientists, generals, and even shopkeepers—all were essential cogs in the machinery that accomplished the final solution.[60]

Additional scholars also point out that a wide range of German soldiers, officials, and civilians were in some way involved in the Holocaust, from clerks and officials in the government to units of the army, police, and the SS.[61][j] Many ministries, including those of armaments, interior, justice, railroads, and foreign affairs, had substantial roles in orchestrating the Holocaust; similarly, German physicians participated in medical experiments and the T-4 euthanasia program as did civil servants;[62] German physicians also made the selections as to who was fit to work and who would die at the concentration camps.[63] Though there was no single department in charge of the Holocaust, the SS and Waffen-SS under Himmler had a leading role and operated with military efficiency in murdering enemies of the Nazi state. From the SS came the SS-Totenkopfverbände concentration camp guard units, the Einsatzgruppen killing squads, and the main administrative offices behind the Holocaust, including the RSHA and WVHA.[64][65] The regular army participated in the atrocities along with the SS on some occasions by taking part in the massacre of Jews in the Soviet Union, Serbia, Poland, and Greece. The German Army also logistically supported the Einsatzgruppen, helped form the ghettos, ran prison camps, occasionally provided concentration camp guards, transported prisoners to camps, had medical experiments performed on prisoners, and substantially used slave labor.[66] Significant numbers of Wehrmacht soldiers accompanied the SS in their deadly tasks or provided other forms of support for killing operations.[67] The murders by the Einsatzgruppen required cooperation between the Einsatzgruppen chief and Wehrmacht unit commander so they could coordinate and control access to and from the execution grounds.[68]

Obedience

Stanley Milgram was one of a number of post-war psychologists and sociologists who tried to address why people obeyed immoral orders in the Holocaust. Milgram's findings demonstrated that reasonable people, when instructed by a person in a position of authority, obeyed commands entailing what they believed to be the suffering of others. After making his results public, Milgram sparked a direct critical response in the scientific community by claiming that "a common psychological process is centrally involved in both" his laboratory experiments and the Holocaust. Professor James Waller, Chair of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Keene State College, formerly Chair of Whitworth College Psychology Department, expressed the opinion that Milgram experiments "do not correspond well" to the Holocaust events:[69]

- The subjects of Milgram's experiments were assured in advance that "no permanent physical damage would result from their actions." However, the Holocaust perpetrators were fully aware of their hands-on killing and maiming of the victims.

- Milgram's guards did not know their victims and were not motivated by racism. On the other hand, the Holocaust perpetrators displayed an "intense devaluation of the victims" through a lifetime of personal development.

- The subjects were not selected for sadism or loyalty to Nazi ideology, and often "exhibited great anguish and conflict" in the experiment, unlike the designers and executioners of the Final Solution (see Holocaust trials), who had a clear "goal" on their hands, set beforehand.

- The experiment lasted for an hour, insufficient time for participants to consider the moral implications of their actions. Meanwhile, the Holocaust lasted for years with ample time for a moral assessment of all individuals and organizations involved.[70]

In the opinion of Thomas Blass—who is the author of a scholarly monograph on the experiment (The Man Who Shocked The World) published in 2004—the historical evidence pertaining to actions of the Holocaust perpetrators speaks louder than words:

My own view is that Milgram's approach does not provide a fully adequate explanation of the Holocaust. While it may well account for the dutiful destructiveness of the dispassionate bureaucrat who may have shipped Jews to Auschwitz with the same degree of routinization as potatoes to Bremerhaven, it falls short when one tries to apply it to the more zealous, inventive, and hate-driven atrocities that also characterized the Holocaust.[71]

Religious hatred and racism

Throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, Jews were subjected to antisemitism based on Christian theology, which blamed them for rejecting and killing Jesus (see Jewish deicide).[72] Numerous attempts to convert the Jews to Christianity in the collective were made by early Christians, but when they refused to convert to Christianity, this made them "pariahs" in the eyes of many Europeans.[73] The consequences which they suffered for resisting conversion to Christianity were varied. An extensive series of attacks was committed against Jews as a result of the religious fervor which accompanied the First and Second Crusades (1095–1149).[73] Jews were slaughtered in the wake of the Italian famine (1315–1317), they were attacked following the outbreak of the Black Death in the Rhineland in 1347, they were expelled from England and Italy in the 1290s, they were expelled from France in 1306 and 1394, and they were expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492 and 1497.[74] By the time of the Reformation in the 16th century, historian Peter Hayes stresses that "hatred of Jews was widespread" throughout Europe.[75]

Martin Luther (a German leader of the Protestant Reformation) made a specific written call for the harsh persecution of the Jewish people in On the Jews and Their Lies, published in 1543. In it, he urged that Jewish synagogues and schools should be set on fire, Jewish prayer books destroyed, rabbis forbidden from preaching, the homes of Jews razed, and the property and money of Jews confiscated.[76] Luther argued that Jews should be shown no mercy or kindness, receive no legal protection and went so far as to state that these "poisonous envenomed worms" should be drafted into forced labor or expelled for all time.[77] American historian Lucy Dawidowicz asserted in her book The War Against the Jews that a clear path of antisemitism passes from Luther to Hitler and that "modern German anti-Semitism is the bastard child of Christian anti-Semitism and German nationalism."[78] Even after the Reformation, Catholics and Lutherans continued to persecute Jews, accusing them of blood libels and subjecting them to pogroms and expulsions.[79][80] The second half of the 19th century saw the emergence of the Völkisch movement in Germany and Austria-Hungary, which was developed and incentivized by authors like Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Paul de Lagarde. The movement advocated racial antisemitism, a form of scientific racism, a pseudo-scientific, biologically based form of racism that viewed Jews as a race which was locked in mortal combat for world domination with the Aryan race.[81]

Some authors, such as the liberal philosopher Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951),[82] Swedish writer Sven Lindqvist, historian Hajo Holborn, and Ugandan academic Mahmood Mandani, have also linked the Holocaust to colonialism, but moreover, they place the tragedy in the context of the European tradition of antisemitism and the genocide of colonized peoples.[83] For instance, Arendt claimed that nationalism and imperialism were literally bridged together by racism.[84] Pseudo-scientific theories which were elaborated upon during the 19th century (e.g. in Arthur de Gobineau's 1853 Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races) were fundamental in preparing the conditions for the Holocaust according to some scholars.[85] Other historical episodes of wholesale slaughter occurred before the Holocaust, however, some scholars still adamantly believe that unlike other genocides, the " Holocaust was a unique event".[86] The philosopher Michel Foucault also traced the origins of the Holocaust to "racial policies" and "state racism", which are subsumed within the framework of "biopolitics".[87]

The Nazis considered it their duty to overcome natural compassion and execute orders for what they believed were higher ideals; in particular, members of the SS perceived that they had a state-legitimized mandate and an obligation to eliminate those who they perceived as being their racial enemies (see Ideology of the SS).[88] Some of the heinous acts committed by the Nazis have been attributed to crowd psychology, and Gustave Le Bon's The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895) provided influence to Hitler's infamous tome, Mein Kampf.[89] Le Bon claimed that Hitler and the Nazis used propaganda to deliberately shape group-think and related behaviors, especially in cases where people committed otherwise aberrant violent acts due to the anonymity resultant from being a member of the collective.[90] Sadistic acts of this sort were notable in the case of the genocide which was committed by members of the Croatian Ustaše, whose enthusiasm and sadism in their killings of Serbs appalled the Italians and the Germans to the point that the German Army field police "moved in and disarmed them" at one point.[91] One might describe the behavior of the Croatians as a sort of quasi-religious eliminationist opportunism, but this same thing might be said of the Germans, whose antisemitism was likewise religious and racialist in nomenclature.[92]

A controversy erupted in 1997 when historian Daniel Goldhagen argued in Hitler's Willing Executioners that ordinary Germans were knowing and willing participants in the Holocaust, which he writes, had its roots in a deep racially motivated eliminationist antisemitism that was uniquely manifested in German society.[93] Historians who disagree with Goldhagen's thesis argue that, while antisemitism undeniably existed in Germany, Goldhagen's idea of a uniquely German "eliminationist" version is untenable.[94] In complete contrast to Goldhagen's position, historian Johann Chapoutot observes,

Culturally speaking, the Nazi ideology advanced by the NSDAP contained only an infinitesimal number of ideas that were genuinely German in origin. Racism, colonialism, anti-Semitism, social Darwinism, and eugenics did not originate between the Rhine and the Memel. Practically speaking, we know the Shoah would have been considerably less murderous if French and Hungarian police forces—not to mention Baltic nationalists, Ukrainian volunteer forces, Polish anti-Semites, and collaborationist politicians, to name only a few—had not supported it so fully and so swiftly: whether or not they knew where the convoys were headed, they were more than happy to rid themselves of their Jewish populations.[95]

Functionalism versus intentionalism

A major issue in contemporary Holocaust studies is the question of functionalism versus intentionalism. The terms were coined during the Cumberland Lodge Conference in May 1979 which was entitled, "The National Socialist Regime and German Society" by the British Marxist historian Timothy Mason in order to describe two schools of thought about the origins of the Holocaust.[96]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Responsibility_for_the_Holocaust

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk