A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| This article is part of a series in |

| Culture of Albania |

|---|

|

|

|

| Religion by country |

|---|

|

|

The most common religion in Albania is Islam, with the second most common religion being Christianity. There are also a number of irreligious Albanians. There are no official statistics regarding the number of practicing religious people per each religious group.[1][2]

Albania has been a secular state since 1912, and as such, is "neutral in questions of belief and conscience":[3] The former socialist government declared Albania the world's first "atheist state", even though the Soviet Union had already done so.[4][5][6][7] Believers faced harsh punishments, and many clergymen were killed. Religious observance and practice is generally lax today, and polls have shown that, compared to the populations of other countries, few Albanians consider religion to be a dominant factor in their lives. When asked about religion, people generally refer to their family's historical religious legacy and not to their own choice of faith.

The 2011 census on religion and ethnicity has been deemed unreliable by the Council of Europe, as well as other internal and external organisations and groups.

History

Antiquity

Christianity spread to urban centers in the region of Albania, at the time composed mostly Epirus Nova and part of south Illyricum, during the later period of Roman era and reached the region relatively early. St. Paul preached the Gospel 'even unto Illyricum' (Romans 15:19). Schnabel asserts that Paul probably preached in Shkodra and Durrës.[8] The steady growth of the Christian community in Dyrrhachium (the Roman name for Epidamnus) led to the creation of a local bishopric in 58 AD. Later, episcopal seats were established in Apollonia, Buthrotum (modern Butrint), and Scodra (modern Shkodra).

One notable Martyr was Saint Astius, who was Bishop of Dyrrachium, who was crucified during the persecution of Christians by the Roman Emperor Trajan. Saint Eleutherius (not to be confused with the later Saint-Pope) was bishop of Messina and Illyria. He was martyred along with his mother Anthia during the anti-Christian campaign of Hadrian.[9]

From the 2nd to the 4th centuries, the main language used to spread the Christian religion was Latin,[10] whereas in the 4th to the 5th centuries it was Greek in Epirus and Macedonia and Latin in Praevalitana and Dardania. Christianity spread to the region during the 4th century, however the Bible cites in Romans that Christianity was spread in the first century. The following centuries saw the erection of characteristic examples of Byzantine architecture such as the churches in Kosine, Mborje and Apollonia.

Christian bishops from what would later become eastern Albania took part in the First Council of Nicaea. Arianism had at that point extended to Illyria, where Arius himself had been exiled to by Constantine.[11]

Middle Ages

Since the early 4th century AD, Christianity had become the established religion in the Roman Empire, supplanting pagan polytheism and eclipsing for the most part the humanistic world outlook and institutions inherited from the Greek and Roman civilizations. Ecclesiastical records during the Slavic invasions are slim. Though the country was in the fold of Byzantium, Christians in the region remained under the jurisdiction of the Roman pope until 732. In that year the iconoclast Byzantine emperor Leo III, angered by archbishops of the region because they had supported Rome in the Iconoclastic Controversy, detached the church of the province from the Roman pope and placed it under the patriarch of Constantinople. When the East-West schism separated the Western Christianity from Greek Christianity, southern Albanian regions retained their ties to Constantinople while the northern areas reverted to the jurisdiction of Rome.

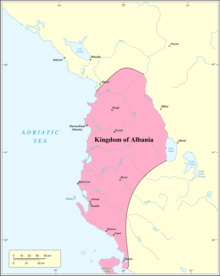

The Albanians first appear in the historical record in Byzantine sources of the 11th century. At this point, they are already fully Christianized. Most Albanian regions belonged to the Eastern Orthodox Church after the schism, but regional Albanian populations gradually became Catholic to secure their independence from various Orthodox political entities[12][13][14] and conversions to Catholicism would be especially notable under the aegis of the Kingdom of Albania.[citation needed] Flirtations with conversions to Catholicism in Central Albanian Principality of Arbanon are reported in the later 12th century,[15] but until 1204 Central and Southern Albanians (in Epirus Nova) remained mostly Orthodox despite the growing Catholic influence in the North and were often linked to Byzantine[16] and Bulgarian state entities[17] Krujë, however, became an important center for the spread of Catholicism. Its bishopric had been Catholic since 1167. It was under direct dependence from the pope and it was the pope himself who consecrated the bishop.[18] Local Albanian nobles maintained good relations with the Papacy. Its influence became so great, that it began to nominate local bishops. The Archbishopric of Durrës, one of the primary bishoprics in Albania had initially remained under the authority of Eastern Orthodox Church after the split despite continuous, but fruitless efforts from Rome to convert it to the Latin Church.[citation needed]

After the Fourth Crusade

However, things changed after the fall of Byzantine Empire in 1204. In 1208, a Catholic archdeacon was elected for the archbishopric of Durrës. After the reconquest of Durrës by the Despotate of Epirus in 1214, the Latin Archbishop of Durrës was replaced by an Orthodox archbishop.[19] According to Etleva Lala, on the edge of the Albanian line in the north was Prizren, which was also an Orthodox bishopric albeit with some Catholic parochial churches,[20] in 1372 received a Catholic bishop due to close relations between the Balsha family and the Papacy.[21]

After the Fourth Crusade, a new wave of Catholic dioceses, churches and monasteries were founded, a number of different religious orders began spreading into the country, and papal missionaries traversed its territories. Those who were not Catholic in Central and North Albania converted and a great number of Albanian clerics and monks were present in the Dalmatian Catholic institutions.[22] The creation of the Kingdom of Albania in 1272, with links to and influence from Western Europe, meant that a decidedly Catholic political structure had emerged, facilitating the further spread of Catholicism in the Balkans.[23] Durrës became again a Catholic archbishopric in 1272. Other territories of the Kingdom of Albania became Catholic centers as well. Butrint in the south, although dependent on Corfu, became Catholic and remained as such during the 14th century. The bishopric of Vlore also converted immediately following the founding of the Kingdom of Albania.[24] Around 30 Catholic churches and monasteries were built during the rule of Helen of Anjou, as Queen consort of the Serbian Kingdom, in North Albania and in Serbia.[23] New bishoprics were created especially in North Albania, with the help of Helen.[25] As Catholic power in the Balkans expanded with Albania as a stronghold, Catholic structures began appearing as far afield as Skopje (which was a mostly Serbian Orthodoxy city at the time[26]) in 1326, with the election of the local bishop there being presided upon by the Pope himself;[27] in the following year, 1327, Skopje sees a Dominican appointed.[26]

However, in Durrës the Byzantine Rite continued to exist for a while after Angevin conquest. This double-line of authority created some confusion in the local population and a contemporary visitor of the country described Albanians as nor they are entirely Catholic or entirely schismatic. In order to fight this religious ambiguity, in 1304, Dominicans were ordered by Pope Benedict XI to enter the country and to instruct the locals in the Latin liturgical rites. Dominican priests were also ordered as bishops in Vlorë and Butrint.[28]

In 1332 a Dominican priest reported that within the Kingdom of Rascia (Serbia) there were two Catholic peoples, the "Latins" and the "Albanians", who both had their own language. The former was limited to coastal towns while the latter was spread out over the countryside, and while the language of the Albanians was noted as quite different from Latin, both peoples are noted as writing with Latin letters. The author, an anonymous Dominican priest, writing in favor of a Western Catholic military action to expel Orthodox Serbia from areas of Albania it controlled in order to restore the power of the Catholic church there, argued that the Albanians and Latin and their clerics were suffering under the "extremely dire bondage of their odious Slav leaders whom they detest" and would eagerly support an expedition of " one thousand French knights and five or six thousand foot soldiers" who, with, their help, could throw off the rule of Rascia.[29]

Although Serbian rulers at earlier times had at times relations with the Catholic West despite being Orthodox, as a counterbalance to Byzantine power, and therefore tolerated the spread of Catholicism in their lands, under the reign of Stefan Dušan the Catholics were persecuted, as were also Orthodox bishops loyal to Constantinople. The Catholic rite was called Latin heresy and, angered in part by marriages of Serbian Orthodox with "half-believers" and the Catholic proselytization of Serbians, Dušan's Code, the Zakonik contained harsh measures against them.[30] However, the persecutions of local Catholics did not begin in 1349 when the Code was declared in Skopje, but much earlier, at least since the beginning of the 14th century. Under these circumstances the relations between local Catholic Albanians and the papal curia became very close, while the previously friendly relations between local Catholics and Serbians deteriorated significantly.[31]

Between 1350 and 1370, the spread of Catholicism in Albania reached its peak. At that period there were around seventeen Catholic bishoprics in the country, which acted not only as centers for Catholic reform within Albania, but also as centers for missionary activity in the neighboring areas, with the permission of the pope.[22] At the end of the 14th century, the previously Orthodox Autocephalous Archbishopric of Ohrid was dismantled in favor of the Catholic rite.[32]

Renaissance

Christianity was later overshadowed by Islam, which became the predominant religion during the invasion from the Ottoman Empire from the 15th century until the year 1912. Many Albanians embraced Islam in different ways.

Albania differs from other regions in the Balkans in that the peak of Islamization in Albania occurred much later: 16th century Ottoman census data showed that sanjaks where Albanians lived remained overwhelmingly Christian with Muslims making up no more than 5% in most areas (Ohrid 1.9%, Shkodra 4.5%, Elbasan 5.5%, Vlora 1.8%, Dukagjin 0%) while during this period Muslims had already risen to large proportions in Bosnia (Bosnia 46%, Herzegovina 43%, urban Sarajevo 100%), Northern Greece (Trikala 17.5%), North Macedonia (Skopje and Bitola both at 75%) and Eastern Bulgaria (Silistra 72%, Chirmen 88%, Nikopol 22%). Later on, in the 19th century, when the process of Islamization had halted in most of the Balkans and some Balkan Christian peoples like Greeks and Serbs had already claimed independence, Islamization continued to make significant progress in Albania, especially in the South.[33]

As a rule, Ottoman rule largely tolerated Christian subjects but it also discriminated against them, turning them into second-class citizens with much higher taxes and various legal restrictions like being unable to take Muslims to court, have horses, have weapons, or have houses overlooking those of Muslims. While Catholicism was chronically held in suspicion by Ottoman authorities, after the conquest of Constantinople, the Ottomans largely allowed the Orthodox church to function unhindered, except during periods when the church was considered politically suspect and thus suppressed with expulsions of bishops and seizure of property and revenues. Conversion during Ottoman times was variously due to calculated attempts to improve social and economic status, due to the successful proselytizing by missionaries, or done out of desperation in very difficult times; in the latter case, the converts often practised crypto-Christianity for long periods. During the Ottoman period, most Christians as well as most Muslims employed a degree of syncretism, still practising various pagan rites; many of these rites are best preserved among mystical orders like the Bektashi.[34]

Unlike some other areas of the Balkans, such as Bulgaria and Bosnia, for the first couple centuries of Ottoman rule, up until the 1500s, Islam remained confined to members of the co-opted aristocracy and a couple scattered military settlements of Yuruks from Anatolia, while the native Albanian peasantry remained overwhelmingly Christian.[35][36] Even long after the fall of Skanderbeg, large regions of the Albanian countryside frequently rebelled against Ottoman rule, often incurring large human costs, including the decimation of whole villages.[37] In the 1570s, a concerted effort by Ottoman rulers to convert the native population to Islam in order to stop the occurrence of seasonal rebellions began in Elbasan and Reka.[38] In 1594, the Pope incited a failed rebellion among Catholic Albanians in the North, promising help from Spain. However the assistance did not come, and when the rebellion was crushed in 1596, Ottoman repression and heavy pressures to convert to Islam were implemented to punish the rebels.[35]

Between 1500 and 1800, impressive ecclesiastical art flourished across Southern Albania. In Moscopole there were over 23 churches during the city's period of prosperity in the mid 18th century.[39] Post-Byzantine architectural style is prevalent in the region, e.g. in Vithkuq, Labove, Mesopotam, Dropull.[40]

Christianity and Islam in the North under Ottoman Rule

Ramadan Marmullaku noted that, in the 1600s, the Ottomans organized a concerted campaign of Islamization that was not typically applied elsewhere in the Balkans, in order to ensure the loyalty of the rebellious Albanian population.[36][42] Although there were certain instances of violently forced conversion, usually this was achieved through debatably coercive economic incentives – in particular, the head tax on Christians was drastically increased.[43] While the tax levied on Albanian Christians in the 1500s amounted to about 45 akçes, in the mid-1600s, it was 780 akçes.[44] Conversion to Islam here was also aided by the dire state of the Catholic church in the period— in the entirety of Albania, there were only 130 Catholic priests, many of these poorly educated.[45] During this period, many Christian Albanians fled into the mountains to found new villages like Theth, or to other countries where they contributed to the emergence of Arvanites, Arbëreshë, and Arbanasi communities in Greece, Italy, and Croatia. While in the first decade of the 17th century, Central and Northern Albania remained firmly Catholic (according to Vatican reports, Muslims were no more than 10% in Northern Albania[46]), by the middle of the 17th century, 30–50% of Northern Albania had converted to Islam, while by 1634 most of Kosovo had also converted.[47] During this time, the Venetian Republic helped to prevent the wholesale Islamisation of Albania, maintaining a hold on parts of the north near the coast.

This period also saw the emergence of Albanian literature, written by Christians such as Pjetër Bogdani. Some of these Christian Albanian thinkers, like Bogdani himself, ultimately advocated for an Albania outside of Ottoman control, and at the end of the 17th century, Bogdani and his colleague Raspasani, raised an army of thousands of Kosovar Albanians in support of the Austrians in the Great Turkish War. However, when this effort failed to expel Ottoman rule from the area yet again, many of Kosovo's Catholics fled to Hungary.[49]

In 1700, the Papacy passed to Pope Clement XI, who was himself of Albanian-Italian origins and held great interest in the welfare of his Catholic Albanian kinsmen, known for composing the Illyricum sacrum. In 1703 he convened the Albanian Council (Kuvendi i Arbënit) in order to organize methods to prevent further apostacy in Albania, and preserve the existence of Catholicism in the land.[50] The widespread survival of Catholicism in northern Albania is largely attributable to the activity of the Franciscan order in the area[45]

In addition to Catholicism and Sunni Islam, there were pockets of Orthodox (some of whom had converted from Catholicism) in Kavajë, Durrës, Upper Reka and some other regions, while Bektashis became established in Kruja, Luma, Bulqiza, Tetova, and Gjakova. Especially in the tribal regions of the North, religious differences were often mitigated by common cultural and tribal characteristics, as well as knowledge of family lineages connecting Albanian Christians and Albanian Muslims. In the 17th century, although many of the rebellions of the century were at least in part motivated by Christian sentiment, it was noted that many Albanian Muslims also took part, and that, despising Ottoman rule no less than their Christian brethren, Albanian Muslims would revolt eagerly if only given the slightest assistance from the Catholic West.[44]

Christianity and Islam in the South under Ottoman Rule

In the late 17th and 18th centuries, especially after numerous rebellions including during the Great Turkish War and subsequent clashes with Orthodox Russia, Ottoman rulers also made concerted efforts to convert the Orthodox Albanians of Southern and Central Albania (as well as neighboring regions of Greece and Macedonia).[51][52] Like in the North, conversion was achieved through a diverse motley of violent, coercive[53] and non-coercive means, but raised taxes were the main factor. Nevertheless, there were specific local cases: in Vlora and the surrounding region, the Christians converted en masse once the area was recaptured from the Christian forces in 1590, because they feared violent retribution for their collaboration.[52][54] In Labëri, meanwhile, mass conversion took place during a famine in which the bishop of Himara and Delvina was said to have forbidden the people from breaking the fast and consuming milk under threat of interminable hell. Across Orthodox regions of Albania, conversion was also helped by the presence of heresies like Arianism and the fact that much of the Orthodox clergy was illiterate, corrupt, and conducted sermons in Greek, a foreign language, as well as the poverty of the Orthodox church.[52] The clergy, largely from the Bosphorus, was distant from its Albanian flocks and also corrupt as well, abusing church tax collection and exacting a heavy tax regime that aggregated on top of punitive taxes imposed directly by the Ottoman state on the rebellious Albanian Christian population aimed at sparking their conversion.[44]

Orthodox areas further north, such as those around Elbasan, were first to convert, during the 1700s, passing through a stage of Crypto-Christianity[55] although in these regions scattered Orthodox holdouts remained (such as around Berat, in Zavalina, and the quite large region of Myzeqe including Fier and Lushnjë) as well as continuing Crypto-Christianity around the region of Shpati among others, where Crypto-Christians formally reverted to Orthodoxy in 1897.[44] Further south, progress was slower. The region of Gjirokastra did not become majority Muslim until around 1875, and even then most Muslims were concentrated in the city of Gjirokastra itself.[52] The same trajectory was true of Albanians in Chamëria, with the majority of Cham Albanians remaining Orthodox until around 1875— at which point Ottoman rule in the Balkans was already collapsing and many Christian Balkan states had already claimed independence (Greece, Serbia, Romania).[51]

At the end of the Ottoman period, Sunni Islam held a slight majority (or plurality) in the Albanian territories. Catholicism still prevailed in the Northwestern regions surrounding Lezha and Shkodra, as well as a few pockets in Kosovo in and around Gjakova, Peja, Vitina, Prizren and Klina. Orthodoxy remained prevalent in various pockets of Southern and Central Albania (Myzeqeja, Zavalina, Shpati as well as large parts of what are now the counties of Vlora, Gjirokastra and Korca). The syncretic Bektashi sect, meanwhile, gained adherence across large parts of the South, especially Skrapari and Dishnica where it is the overwhelming majority. This four-way division of Albanians between Sunnis (who became either a plurality or a majority), Orthodox, Bektashis and Catholics, with the later emergence of Albanian Uniates, Protestants and atheists, prevented Albanian nationalism as it emerged from tying itself to any particular faith, instead promoting harmony between the different confessions and using the shared Albanian language, Albanian history and Albanian ethnic customs as unifying themes. Despite this, Bektashi tekkes in the South and Catholic churches in the North were both used by the nationalist movement as places of dissemination of nationalist ideals.

Modern

Independence

During the 20th century after Independence (1912) the democratic, monarchic and later the totalitarian regimes followed a systematic dereligionization of the nation and the national culture. Albania never had an official state religion either as a republic or as a kingdom after its restoration in 1912.[56] Religious tolerance in Albania was born of national expediency and a general lack of religious convictions.[57]

Monarchy

Originally under the monarchy, institutions of all confessions were put under state control. In 1923, following the government program, the Albanian Muslim congress convened at Tirana decided to break with the Caliphate, established a new form of prayer (standing, instead of the traditional salah ritual), banished polygamy and did away with the mandatory use of veil (hijab) by women in public, which had been forced on the urban population by the Ottomans during the occupation.[58]

In 1929 the Albanian Orthodox Church was declared autocephalous.[59]

A year later, in 1930, the first official religious census was carried out. Reiterating conventional Ottoman data from a century earlier which previously covered double the new state's territory and population, 50% of the population was grouped as Sunni Muslim, 20% as Orthodox Christian, 20% as Bektashi Muslim and 10% as Catholic Christian.

The monarchy was determined that religion should no longer be a foreign-oriented master dividing the Albanians, but a nationalized servant uniting them. It was at this time that newspaper editorials began to disparage the almost universal adoption of Muslim and Christian names, suggesting instead that children be given neutral Albanian names.

Official slogans began to appear everywhere. "Religion separates, patriotism unites." "We are no longer Muslim, Orthodox, Catholic, we are all Albanians." "Our religion is Albanism." The national hymn characterized neither Muhammad nor Jesus Christ, but King Zogu as "Shpëtimtari i Atdheut" (Savior of the Fatherland). The hymn to the flag honored the soldier dying for his country as a "Saint." Increasingly the mosque and the church were expected to function as servants of the state, the patriotic clergy of all faiths preaching the gospel of Albanism.

Monarchy stipulated that the state should be neutral, with no official religion and that the free exercise of religion should be extended to all faiths. Neither in government nor in the school system should favor be shown to any one faith over another. Albanism was substituted for religion, and officials and schoolteachers were called "apostles" and "missionaries." Albania's sacred symbols were no longer the cross and the crescent, but the Flag and the King. Hymns idealizing the nation, Skanderbeg, war heroes, the king and the flag predominated in public-school music classes to the exclusion of virtually every other theme.

The first reading lesson in elementary schools introduced a patriotic catechism beginning with this sentence, "I am an Albanian. My country is Albania." Then there follows in poetic form, "But man himself, what does he love in life?" "He loves his country." "Where does he live with hope? Where does he want to die?" "In his country." "Where may he be happy, and live with honor?" "In Albania."[60]

Italian occupation

On 7 April 1939, Albania was invaded by Italy under Benito Mussolini, which had long taken an interest in gaining dominance over Albania as an Italian sphere of influence during the interwar period.[61] The Italians attempted to win the sympathies of the Muslim Albanian population by proposing to build a large mosque in Rome, though the Vatican opposed this measure and nothing came of it in the end.[62] The Italian occupiers also won Muslim Albanian sympathies by causing their working wages to rise.[62] Mussolini's son-in-law Count Ciano also replaced the leadership of the Sunni Muslim community, which had recognized the Italian regime in Albania, with clergy that aligned with Italian interests, with a compliant "Moslem Committee" organization, and Fischer notes that "the Moslem community at large accepted this change with little complaint".[62] Most of the Bektashi order and its leadership were against the Italian occupation and remained an opposition group.[62] Fischer suspects that the Italians eventually tired of the opposition of the Bektashi Order, and had its head, Nijaz Deda, murdered.[62]

The Albanian Orthodox hierarchy also acquiesced in the occupation, according to Fischer. The primate of the church, Archbishop Kisi, along with three other bishops, expressed formal approval of the Italian invasion in 1939.[62][63]

The Catholic Church and many Catholics were supportive of the invasion, but Fischer states there were many exceptions, particularly of among the village priests since most of them were trained in Albania and were quite nationalistic. Some of them even left Albania after the Italian invasion. But the hierarchy on the other hand was quite supportive, with the apostolic delegate seeing it as a possibility to give more freedom to Albanians who wanted to become Catholic. The Catholic Church had also the most financial support per member during the Italian occupation.[62]

| Last Zog budget | First Italian budget | Evolution from the Zog to the Italian era | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunni Muslims | 50,000 francs | 375,000 francs | + 750% |

| Albanian Orthodox Church | 35,000 francs | 187,500 francs | + 535% |

| Catholic Church in Albania | - | 156,000 francs | - |

| Bektashi Order in Albania | - | - | - |

Communism

Before the Communists took power in 1944, it was estimated that of Albania's population of roughly 1,180,500 persons, about 70% belonged to Islamic sects while 30% belonged to Christian sects. Among the Muslims, at least 200,000 (or 17%) were Bektashis, while most of the rest were Sunnis, in addition to a collection of much smaller orders. Among the Christians, 212,500 (18%) were Orthodox while 142,000 (12%) were Catholic.[64]

The Agrarian Reform Law of August 1946 nationalized most property of religious institutions, including the estates of monasteries, orders, and dioceses. Many clergy and believers were tried, tortured, and executed. All foreign Roman Catholic priests, monks, and nuns were expelled in 1946.[65]

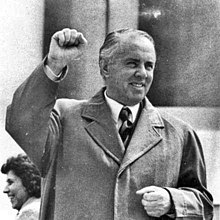

Religious communities or branches that had their headquarters outside the country, such as the Jesuit and Franciscan orders, were henceforth ordered to terminate their activities in Albania. Religious institutions were forbidden to have anything to do with the education of the young, because that had been made the exclusive province of the state. All religious communities were prohibited from owning real estate and from operating philanthropic and welfare institutions and hospitals. Although there were tactical variations in First Secretary of the Communist Party Enver Hoxha's approach to each of the major denominations, his overarching objective was the eventual destruction of all organized religion in Albania. Between 1945 and 1953, the number of priests was reduced drastically and the number of Roman Catholic churches was decreased from 253 to 100, and all Catholics were stigmatized as fascists.[65]

The campaign against religion peaked in the 1960s. Beginning in 1967 the Albanian authorities began a violent campaign to try to eliminate religious life in Albania. Despite complaints, even by Party of Labour of Albania members, all churches, mosques, tekkes, monasteries, and other religious institutions were either closed down or converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, or workshops by the end of 1967.[66] By May 1967, religious institutions had been forced to relinquish all 2,169 churches, mosques, cloisters, and shrines in Albania, many of which were converted into cultural centres for young people. As the literary monthly Nendori reported the event, the youth had thus "created the first atheist nation in the world."[65]

The clergy were publicly vilified and humiliated, their vestments taken and desecrated. More than 200 clerics of various faiths were imprisoned, others were forced to seek work in either industry or agriculture, and some were executed or starved to death. The monastery of the Franciscan order in Shkodër was set on fire, which resulted in the death of four elderly monks.[65]

A major center for anti-religious propaganda was the National Museum of Atheism (Albanian: Muzeu Ateist) in Shkodër, the city viewed by the government as the most religiously conservative.[67][68]

Article 37 of the Albanian Constitution of 1976 stipulated, "The State recognises no religion, and supports atheistic propaganda in order to implant a scientific materialistic world outlook in the people",[69] and the penal code of 1977 imposed prison sentences of three to ten years for "religious propaganda and the production, distribution, or storage of religious literature."[65] A new decree that in effect targeted Albanians with Islamic and religiously-tinged Christian names stipulated that citizens whose names did not conform to "the political, ideological, or moral standards of the state" were to change them. It was also decreed that towns and villages with religious names must be renamed.[65] Hoxha's brutal antireligious campaign succeeded in eradicating formal worship, but some Albanians continued to practise their faith clandestinely, risking severe punishment.[65] Individuals caught with Bibles, icons, or other religious objects faced long prison sentences.[65] Religious weddings were prohibited.[70] Parents were afraid to pass on their faith, for fear that their children would tell others. Officials tried to entrap practising Christians and Muslims during religious fasts, such as Lent and Ramadan, by distributing food at schools and workplaces during those fasting hours, and then publicly denouncing those who refused to eat during such times, and clergy who conducted secret services were incarcerated.[65]

The article was interpreted as violating The United Nations Charter (chapter 9, article 55) which declares that religious freedom is an inalienable human right. The first time that the question of religious oppression in Albania came before the United Nations' Commission on Human Rights at Geneva was as late as 7 March 1983. A delegation from Denmark got its protest over Albania's violation of religious liberty placed on the agenda of the thirty-ninth meeting of the commission, item 25, reading, "Implementation of the Declaration on the Elimination of all Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination based on Religion or Belief." There was little consequence at first, but on 20 July 1984 a member of the Danish Parliament inserted an article in one of Denmark's major newspapers protesting the violation of religious freedom in Albania.[citation needed]

After the death of Enver Hoxha in 1985, his successor, Ramiz Alia, adopted a relatively tolerant stance toward religious practice, referring to it as "a personal and family matter." Émigré clergymen were permitted to reenter the country in 1988 and officiate at religious services. Mother Teresa, an ethnic Albanian, visited the country in 1989, where she was received in Tirana by the foreign minister and by Hoxha's widow and where she laid a wreath on Hoxha's grave. In December 1990, the ban on religious observance was officially lifted, in time to allow thousands of Christians to attend Christmas services.[71]

The atheistic campaign had significant results especially to the Greek minority, since religion which was now criminalized was traditionally an integral part of its cultural life and identity.[72]

Religions

Islam

Islam was first introduced to Albania in the 15th century after the Ottoman conquest of the area.[73][74] It is the largest religion in the country, representing 56% of the population according to the 2011 census.[75] One of the major legacies of nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule was that the majority of Albanians had converted to Islam. Therefore, the nation emerged as a Muslim-majority country after Albania's independence in November 1912.

In the North, the spread of Islam was slower due to the resistance of the Roman Catholic Church and the region's mountainous terrain. In the center and south, however, Catholicism was not as strong and by the end of the 17th century the region had largely adopted the religion of the growing Albanian Muslim elite. The existence of an Albanian Muslim class of pashas and beys who played an increasingly important role in Ottoman political and economic life became an attractive career option for most Albanians. Widespread illiteracy and the absence of educated clergy also played roles in the spread of Islam, especially in northern Albanian-inhabited regions. During the 17th and 18th centuries Albanians converted to Islam in large numbers, often under sociopolitical duress experienced as repercussions for rebelling and for supporting the Catholic powers of Venice and Austria and Orthodox Russia in their wars against the Ottomans.[76][77]

In the 20th century, the power of Muslim, Catholic and Orthodox clergy was weakened during the years of monarchy and it was eradicated during the 1940s and 1950s, under the state policy of obliterating all organized religion from Albanian territories.

During the Ottoman invasion the Muslims of Albania were divided into two main communities: those associated with Sunni Islam and those associated with Bektashi Shiism, a mystical Dervish order that came to Albania through the Albanian Janissaries that served in the Ottoman army and whose members practised Albanian pagan rites under a nominal Islamic cover.[citation needed] After the Bektashis were banned in Turkey in 1925 by Atatürk, the order moved its headquarters to Tirana and the Albanian government subsequently recognized it as a body independent from Sunnism. Sunni Muslims were estimated to represent approximately 50% of the country's population before 1939, while Bektashi represented another 20%. There is also a relatively small minority which belongs to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Muslim populations have been particularly strong in eastern and northern Albania and among Albanians living in Kosovo and Macedonia.

Islam (Sunni)

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2017) |

Sunni Muslims have historically lived in the cities of Albania, while Bektashis mainly live in remote areas, whereas Orthodox Christians mainly live in the south, and Roman Catholics mainly live in the north of the country. However, this division does not apply nowadays. In a study by Pew Research, 65% of Albanian Muslims did not specify a branch of Islam that they belonged to.[78] The Albanian census doesn't differentiate between Bektashis and Sunnis, but instead between Bektashis and "Muslims", but since Bektashis are in fact Muslim many were listed as Muslims. Bektashi-majority areas include Skrapari, Dishnica, Erseka and Bulqiza while Bektashis also have large, possibly majority concentrations in Kruja, Mallakastra, Tepelena, large pockets of the Gjirokastër and Delvina Districts (i.e. Gjirokastër itself, Lazarat, etc.), and Western and Northeastern parts of the Vlora district. There are also historically substantial Bektashi minorities around Elbasan, Berat, Leskovik, Perm, Saranda and Pogradec. In Kosovo and Macedonia there were pockets of Bektashis in Gjakova, Prizren and Tetova. In the Albanian census, a few of these areas, such as Skrapari and Dishnica, saw the Bektashi population mostly labeled "Bektashi" while in most other areas such as Kruja it was mostly labeled "Muslim". The classification of children of mixed marriages between Sunnis and Bektashis or the widespread phenomenon of both groups marrying Orthodox Albanians also have inconsistent classification and oftentimes the offspring of such unions associate with both of their parents' faiths and occasionally practice both.

In December 1992 Albania became a full member of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation).

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Religion_in_Albania

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk