A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 35.3 million (29.6 million under the mandate of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and 5.9 million under UNRWA's mandate | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 7.0 million |

| Europe and North Asia | 12.4 million |

| Asia and the Pacific | 6.8 million |

| Middle East and North Africa | 2.4 million |

| Americas | 800,000 |

| Legal status of persons |

|---|

|

| Birthright |

| Nationality |

| Immigration |

| Part of a series on |

| Immigration |

|---|

|

| General |

| History and law |

| Social processes |

| Political theories |

| Opposition and reform |

| Causes topics |

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a person who has lost the protection of their country of origin and who cannot or is unwilling to return there due to well-founded fear of persecution.[2] Such a person may be called an asylum seeker until granted refugee status by the contracting state or the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)[3] if they formally make a claim for asylum.[4]

Etymology and usage

In English, the term refugee derives from the root word refuge, from Old French refuge, meaning "hiding place". It refers to "shelter or protection from danger or distress", from Latin fugere, "to flee", and refugium, "a taking refuge, place to flee back to". In Western history, the term was first applied to French Protestant Huguenots looking for a safe place against Catholic persecution after the first Edict of Fontainebleau in 1540.[5][6] The word appeared in the English language when French Huguenots fled to Britain in large numbers after the 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau (the revocation of the 1598 Edict of Nantes) in France and the 1687 Declaration of Indulgence in England and Scotland.[7] The word meant "one seeking asylum", until around 1916, when it evolved to mean "one fleeing home", applied in this instance to civilians in Flanders heading west to escape fighting in World War I.[8]

Definitions

The first modern definition of an international refugee status came with the League of Nations in 1921 from the Commission for Refugees. Following World War II and in response to the large numbers of people fleeing Eastern Europe, the United Nations passed the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. It defines "refugee" in Article 1.A.2 as any person who:[3]

owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.[3]

In 1967 the definition was basically confirmed by the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees.

People fleeing from war, natural disasters, or poverty are generally not encompassed by the international right of asylum. However, many countries have implemented laws to protect also those Displaced Persons. Accordingly, the Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa expanded the 1951 definition, which the Organization of African Unity adopted in 1969:

Every person who, owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his country of origin or nationality, is compelled to leave his place of habitual residence in order to seek refuge in another place outside his country of origin or nationality.[9]

The 1984 the regional, non-binding Latin-American Cartagena Declaration on Refugees included the following definition of refugees:

persons who have fled their country because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.[10]

As of 2011 the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) itself, in addition to the 1951 definition, recognizes the following persons as refugees:

who are outside their country of nationality or habitual residence and unable to return there owing to serious and indiscriminate threats to life, physical integrity or freedom resulting from generalized violence or events seriously disturbing public order.[11]

The European Union passed minimum standards as part of its definition of refugee, underlined by article 2 (c) of Directive No. 2004/83/EC, essentially reproducing the narrow definition of refugee offered by the UN 1951 Convention. Nevertheless, by virtue of articles 2 (e) and 15 of the same Directive, persons who have fled a war-caused generalized violence are, at certain conditions, eligible for a complementary form of protection, called subsidiary protection. The same form of protection is foreseen for displaced people who, without being refugees, are nevertheless exposed, if returned to their countries of origin, to death penalty, torture or other inhuman or degrading treatments.

Related terms

Refugee resettlement is defined as "an organized process of selection, transfer and arrival of individuals to another country. This definition is restrictive, as it does not account for the increasing prevalence of unmanaged migration processes."[12]

The term refugee relocation refers to "a non‐organized process of individual transfer to another country."[12]

Refugee settlement refers to "the process of basic adjustment to life ‒ often in the early stages of transition to the new country ‒ including securing access to housing, education, healthcare, documentation and legal rights employment is sometimes included in this process, but the focus is generally on short‐term survival needs rather than long‐term career planning."[12]

Refugee integration means "a dynamic, long‐term process in which a newcomer becomes a full and equal participant in the receiving society... Compared to the general construct of settlement, refugee integration has a greater focus on social, cultural and structural dimensions. This process includes the acquisition of legal rights, mastering the language and culture, reaching safety and stability, developing social connections and establishing the means and markers of integration, such as employment, housing and health."[12]

Refugee workforce integration is understood to be "a process in which refugees engage in economic activities (employment or self‐employment) which are commensurate with individuals' professional goals and previous qualifications and experience, and provide adequate economic security and prospects for career advancement."[12]

History

The idea that a person who sought sanctuary in a holy place could not be harmed without inviting divine retribution was familiar to the ancient Greeks and ancient Egyptians. However, the right to seek asylum in a church or other holy place was first codified in law by King Æthelberht of Kent in about AD 600. Similar laws were implemented throughout Europe in the Middle Ages. The related concept of political exile also has a long history: Ovid was sent to Tomis; Voltaire was sent to England. By the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, nations recognized each other's sovereignty. However, it was not until the advent of romantic nationalism in late 18th-century Europe that nationalism gained sufficient prevalence for the phrase country of nationality to become practically meaningful, and for border crossing to require that people provide identification.

The term "refugee" sometimes applies to people who might fit the definition outlined by the 1951 Convention, were it applied retroactively. There are many candidates. For example, after the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685 outlawed Protestantism in France, hundreds of thousands of Huguenots fled to England, the Netherlands, Switzerland, South Africa, Germany and Prussia. The repeated waves of pogroms that swept Eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries prompted mass Jewish emigration (more than 2 million Russian Jews emigrated in the period 1881–1920). Beginning in the 19th century, Muslim people emigrated to Turkey from Europe.[13] The Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 caused 800,000 people to leave their homes.[14] Various groups of people were officially designated refugees beginning in World War I. However, when the First World War began, there were no rules in international law specifically dealing with the situation of refugees.[15]

League of Nations

The first international co-ordination of refugee affairs came with the creation by the League of Nations in 1921 of the High Commission for Refugees and the appointment of Fridtjof Nansen as its head. Nansen and the commission were charged with assisting the approximately 1,500,000 people who fled the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent civil war (1917–1921),[16] most of them aristocrats fleeing the Communist government. It is estimated that about 800,000 Russian refugees became stateless when Lenin revoked citizenship for all Russian expatriates in 1921.[17]

In 1923, the mandate of the commission was expanded to include the more than one million Armenians who left Turkish Asia Minor in 1915 and 1923 due to a series of events now known as the Armenian genocide. Over the next several years, the mandate was expanded further to cover Assyrians and Turkish refugees.[18] In all of these cases, a refugee was defined as a person in a group for which the League of Nations had approved a mandate, as opposed to a person to whom a general definition applied.[citation needed]

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey involved about two million people (around 1.5 million Anatolian Greeks and 500,000 Muslims in Greece) most of whom were forcibly repatriated and denaturalized[clarification needed] from homelands of centuries or millennia (and guaranteed the nationality of the destination country) by a treaty promoted and overseen by the international community as part of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923).[A]

The U.S. Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act in 1921, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924. The Immigration Act of 1924 was aimed at further restricting the Southern and Eastern Europeans, especially Jews, Italians and Slavs, who had begun to enter the country in large numbers beginning in the 1890s.[19] Most European refugees (principally Jews and Slavs) fleeing the Nazis and the Soviet Union were barred from going to the United States until after World War II, when Congress enacted the temporary Displaced Persons Act in 1948.[20]

In 1930, the Nansen International Office for Refugees (Nansen Office) was established as a successor agency to the commission. Its most notable achievement was the Nansen passport, a refugee travel document, for which it was awarded the 1938 Nobel Peace Prize. The Nansen Office was plagued by problems of financing, an increase in refugee numbers, and a lack of co-operation from some member states, which led to mixed success overall.

However, the Nansen Office managed to lead fourteen nations to ratify the 1933 Refugee Convention, an early, and relatively modest, attempt at a human rights charter, and in general assisted around one million refugees worldwide.[21]

Rise of Nazism, 1933 to 1944

The rise of Nazism led to such a very large increase in the number of refugees from Germany that in 1933 the League created a high commission for refugees coming from Germany. Besides other measures by the Nazis which created fear and flight, Jews were stripped of German citizenship [B] by the Reich Citizenship Law of 1935.[22] On 4 July 1936 an agreement was signed under League auspices that defined a refugee coming from Germany as "any person who was settled in that country, who does not possess any nationality other than German nationality, and in respect of whom it is established that in law or in fact he or she does not enjoy the protection of the Government of the Reich" (article 1).[C]

The mandate of the High Commission was subsequently expanded to include persons from Austria and Sudetenland, which Germany annexed after 1 October 1938 in accordance with the Munich Agreement. According to the Institute for Refugee Assistance, the actual count of refugees from Czechoslovakia on 1 March 1939 stood at almost 150,000.[23] Between 1933 and 1939, about 200,000 Jews fleeing Nazism were able to find refuge in France,[24] while at least 55,000 Jews were able to find refuge in Palestine[25] before the British authorities closed that destination in 1939.

On 31 December 1938 both the Nansen Office and High Commission were dissolved and replaced by the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees under the Protection of the League.[18] This coincided with the flight of 500,000 Spanish Republicans, soldiers as well as civilians, to France after their defeat by the Nationalists in 1939 in the Spanish Civil War.[26]

The conflict and political instability during World War II led to massive numbers of refugees (see World War II evacuation and expulsion). In 1943, the Allies of World War II created the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) to provide aid to areas liberated from Axis powers of World War II, including parts of Europe and China. By the end of the War, Europe had more than 40 million refugees.[27][28] UNRRA was involved in returning over seven million refugees, then commonly referred to as displaced persons or DPs, to their country of origin and setting up displaced persons camps for one million refugees who refused to be repatriated. Even two years after the end of War, some 850,000 people still lived in DP camps across Western Europe.[29] After the establishment of Israel in 1948, Israel accepted more than 650,000 Jewish refugees by 1950. By 1953, over 250,000 refugees were still in Europe, most of them old, infirm, crippled, or otherwise disabled.

Post-World War II population transfers

After the Soviet armed forces captured eastern Poland from the Germans in 1944, the Soviets unilaterally declared a new frontier between the Soviet Union and Poland approximately at the Curzon Line, despite the protestations from the Polish government-in-exile in London and the western Allies at the Teheran Conference and the Yalta Conference of February 1945. After the German surrender on 7 May 1945, the Allies occupied the remainder of Germany, and the Berlin declaration of 5 June 1945 confirmed the unfortunate division of Allied-occupied Germany according to the Yalta Conference, which stipulated the continued existence of the German Reich as a whole, which would include its eastern territories as of 31 December 1937. This did not impact on Poland's eastern border, and Stalin refused to be removed from these eastern Polish territories.

In the last months of World War II, about five million German civilians from the German provinces of East Prussia, Pomerania and Silesia fled the advance of the Red Army from the east and became refugees in Mecklenburg, Brandenburg and Saxony. Since the spring of 1945, the Poles had been forcefully expelling the remaining German population in these provinces. When the Allies met in Potsdam on 17 July 1945 at the Potsdam Conference, a chaotic refugee situation faced the occupying powers. The Potsdam Agreement, signed on 2 August 1945, defined the Polish western border as that of 1937, (Article VIII) Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference Archived 31 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine placing one fourth of Germany's territory under the Provisional Polish administration. Article XII ordered that the remaining German populations in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary be transferred west in an "orderly and humane" manner. Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference Archived 31 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine (See Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–50).)

Although not approved by Allies at Potsdam, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans living in Yugoslavia and Romania were deported to slave labour in the Soviet Union, to Allied-occupied Germany, and subsequently to the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), Austria and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). This entailed the largest population transfer in history. In all 15 million Germans were affected, and more than two million perished during the expulsions of the German population.[30][31][32][33] (See Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950).) Between the end of War and the erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961, more than 563,700 refugees from East Germany traveled to West Germany for asylum from the Soviet occupation.

During the same period, millions of former Russian citizens were forcefully repatriated against their will into the USSR.[34] On 11 February 1945, at the conclusion of the Yalta Conference, the United States and United Kingdom signed a Repatriation Agreement with the USSR.[35] The interpretation of this Agreement resulted in the forcible repatriation of all Soviets regardless of their wishes. When the war ended in May 1945, British and United States civilian authorities ordered their military forces in Europe to deport to the Soviet Union millions of former residents of the USSR, including many persons who had left Russia and established different citizenship decades before. The forced repatriation operations took place from 1945 to 1947.[36]

At the end of World War II, there were more than 5 million "displaced persons" from the Soviet Union in Western Europe. About 3 million had been forced laborers (Ostarbeiters)[37] in Germany and occupied territories.[38][39] The Soviet POWs and the Vlasov men were put under the jurisdiction of SMERSH (Death to Spies). Of the 5.7 million Soviet prisoners of war captured by the Germans, 3.5 million had died while in German captivity by the end of the war.[40][41] The survivors on their return to the USSR were treated as traitors (see Order No. 270).[42] Over 1.5 million surviving Red Army soldiers imprisoned by the Nazis were sent to the Gulag.[43]

Poland and Soviet Ukraine conducted population exchanges following the imposition of a new Poland-Soviet border at the Curzon Line in 1944. About 2,100,000 Poles were expelled west of the new border (see Repatriation of Poles), while about 450,000 Ukrainians were expelled to the east of the new border. The population transfer to Soviet Ukraine occurred from September 1944 to May 1946 (see Repatriation of Ukrainians). A further 200,000 Ukrainians left southeast Poland more or less voluntarily between 1944 and 1945.[44]

According to the report of the U.S. Committee for Refugees (1995), 10 to 15 percent of 7.5 million Azerbaijani population were refugees or displaced people.[45] Most of them were 228,840 refugee people of Azerbaijan who fled from Armenia in 1988 as a result of deportation policy of Armenia against ethnic Azerbaijanis.[46]

During the 1948 Palestine War, some 700,000[47] Palestinian Arabs or 85% of the Palestinian Arab population of territories that became Israel fled or were expelled from their homes by the Israelis.[47]

The International Refugee Organization (IRO) was founded on 20 April 1946, and took over the functions of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, which was shut down in 1947. While the handover was originally planned to take place at the beginning of 1947, it did not occur until July 1947.[48] The International Refugee Organization was a temporary organization of the United Nations (UN), which itself had been founded in 1945, with a mandate to largely finish the UNRRA's work of repatriating or resettling European refugees. It was dissolved in 1952 after resettling about one million refugees.[49] The definition of a refugee at this time was an individual with either a Nansen passport or a "certificate of identity" issued by the International Refugee Organization.

The Constitution of the International Refugee Organization, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 15 December 1946, specified the agency's field of operations. Controversially, this defined "persons of German ethnic origin" who had been expelled, or were to be expelled from their countries of birth into the postwar Germany, as individuals who would "not be the concern of the Organization." This excluded from its purview a group that exceeded in number all the other European displaced persons put together. Also, because of disagreements between the Western allies and the Soviet Union, the IRO only worked in areas controlled by Western armies of occupation.

Refugee studies

With the occurrence of major instances of diaspora and forced migration, the study of their causes and implications has emerged as a legitimate interdisciplinary area of research, and began to rise by mid to late 20th century, after World War II. Although significant contributions had been made before, the latter half of the 20th century saw the establishment of institutions dedicated to the study of refugees, such as the Association for the Study of the World Refugee Problem, which was closely followed by the founding of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. In particular, the 1981 volume of the International Migration Review defined refugee studies as "a comprehensive, historical, interdisciplinary and comparative perspective which focuses on the consistencies and patterns in the refugee experience."[50] Following its publishing, the field saw a rapid increase in academic interest and scholarly inquiry, which has continued to the present. Most notably in 1988, the Journal of Refugee Studies was established as the field's first major interdisciplinary journal.[51]

The emergence of refugee studies as a distinct field of study has been criticized by scholars due to terminological difficulty. Since no universally accepted definition for the term "refugee" exists, the academic respectability of the policy-based definition, as outlined in the 1951 Refugee Convention, is disputed. Additionally, academics have critiqued the lack of a theoretical basis of refugee studies and dominance of policy-oriented research. In response, scholars have attempted to steer the field toward establishing a theoretical groundwork of refugee studies through "situating studies of particular refugee (and other forced migrant) groups in the theories of cognate areas (and major disciplines), an opportunity to use the particular circumstances of refugee situations to illuminate these more general theories and thus participate in the development of social science, rather than leading refugee studies into an intellectual cul-de-sac."[52] Thus, the term refugee in the context of refugee studies can be referred to as "legal or descriptive rubric", encompassing socioeconomic backgrounds, personal histories, psychological analyses, and spiritualities.[52]

UN Refugee Agencies

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

UNHCR

Headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) was established on 14 December 1950. It protects and supports refugees at the request of a government or the United Nations and assists in providing durable solutions, such as return or resettlement. All refugees in the world are under UNHCR mandate except Palestinian refugees, who fled the current state of Israel between 1947 and 1949, as a result of the 1948 Palestine War. These refugees are assisted by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). UNHCR also provides protection and assistance to other categories of displaced persons: asylum seekers, refugees who returned home voluntarily but still need help rebuilding their lives, local civilian communities directly affected by large refugee movements, stateless people and so-called internally displaced people (IDPs), as well as people in refugee-like and IDP-like situations. The agency is mandated to lead and co-ordinate international action to protect refugees and to resolve refugee problems worldwide. Its primary purpose is to safeguard the rights and well-being of refugees. It strives to ensure that everyone can exercise the right to seek asylum and find safe refuge in another state or territory and to offer "durable solutions" to refugees and refugee hosting countries.

UNRWA

Unlike other refugee groups, the UN created a specific entity called the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) in the aftermath of the war in 1948, which led to a serious refugee crisis in the Arab region, and was responsible for the displacement of 700,000 Palestinian refugees. This number has gone up to at least 5 million refugees in the last 70 years.[53]

The United Nations defines Palestinian refugees as "persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict."[53]

The population of Palestinian refugees continues to grow due to multiple UNRWA reclassifications of what is considered to be a refugee. "In 1965, UNRWA changed the eligibility requirements to be a Palestinian refugee to include third-generation descendants, and in 1982, it extended it again, to include all descendants of Palestine refugee males, including legally adopted children, regardless of whether they had been granted citizenship elsewhere. This classification process is inconsistent with how all other refugees in the world are classified, including the definition used by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the laws concerning refugees in the United States."[54]

Another refugee wave started in 1967 after the Six-day-War, where mostly Palestinians living in Gaza and the West Bank were victims of displacement.[55] According to the United Nations, Palestinian refugees struggle with access to health care, food, clean water, sanitation, environmental health and infrastructure, education, and technology.[56] According to the report, food, shelter, and environmental health are a human's basic needs.[56] United Nations agency UNRWA (The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) focuses on addressing these issues to relieve Palestinians from any harm. UNRWA was established as a temporary agency that would carry out a humanitarian response mandate for Palestinian refugees in Gaza, the West Bank, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon.[57]

The responsibilities for the assistance for protection for Palestinian refugees and human development were originally left to the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP). This agency failed to function, which led the agency to stop working.[55] UNRWA took over these responsibilities and expanded their mandate from just humanitarian emergency relief to including human development and protection of the Palestinian society.[55] Communication with host countries where UNRWA is operating (Syria, Jordan and Lebanon) is very important as the agency's mandate changes per region.[58] UNRWA's Medium Term Strategy is a report that lists all the issues that the Palestinians are facing and UNRWA's plan to mitigate the severeness of the issues. The report shows that UNRWA focusses mostly on food assistance, health care, education and shelter for Palestinian refugees.[56] UNRWA has succeeded in placing over 700 schools with over 500,000 students, 140 health centers, 113 women community centers, and has awarded over 475,000 loans.[58] UNRWA's funding relies mostly on voluntary donations. Fluctuations in these donations result in constraints in carrying out the mandate.[59]

Acute and temporary protection

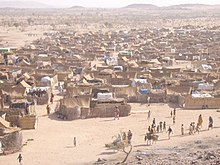

Refugee camp

A refugee camp is a place built by governments or NGOs (such as the Red Cross) to receive refugees, internally displaced persons or sometimes also other migrants. It is usually designed to offer acute and temporary accommodation and services and any more permanent facilities and structures often banned. People may stay in these camps for many years, receiving emergency food, education and medical aid until it is safe enough to return to their country of origin. There, refugees are at risk of disease, child soldier and terrorist recruitment, and physical and sexual violence. There are estimated to be 700 refugee camp locations worldwide.[60]

Urban refugee

Not all refugees who are supported by the UNHCR live in refugee camps. A significant number, more than half, live in urban settings,[61] such as the ~60,000 Iraqi refugees in Damascus (Syria),[62] and the ~30,000 Sudanese refugees in Cairo (Egypt).[63]

Durable solutions

The residency status in the host country whilst under temporary UNHCR protection is very uncertain as refugees are only granted temporary visas that have to be regularly renewed. Rather than only safeguarding the rights and basic well-being of refugees in the camps or in urban settings on a temporary basis the UNHCR's ultimate goal is to find one of the three durable solutions for refugees: integration, repatriation, resettlement.[64]

Integration and naturalisation

Local integration is aiming at providing the refugee with the permanent right to stay in the country of asylum, including, in some situations, as a naturalized citizen. It follows the formal granting of refugee status by the country of asylum. It is difficult to quantify the number of refugees who settled and integrated in their first country of asylum and only the number of naturalisations can give an indication.[citation needed] In 2014 Tanzania granted citizenship to 162,000 refugees from Burundi and in 1982 to 32,000 Rwandan refugees.[65] Mexico naturalised 6,200 Guatemalan refugees in 2001.[66]

Voluntary return

Voluntary return of refugees into their country of origin, in safety and dignity, is based on their free will and their informed decision. In the last couple of years parts of or even whole refugee populations were able to return to their home countries: e.g. 120,000 Congolese refugees returned from the Republic of Congo to the DRC,[67] 30,000 Angolans returned home from the DRC[68] and Botswana, Ivorian refugees returned from Liberia, Afghans from Pakistan, and Iraqis from Syria. In 2013, the governments of Kenya and Somalia also signed a tripartite agreement facilitating the repatriation of refugees from Somalia.[69] The UNHCR and the IOM offer assistance to refugees who want to return voluntarily to their home countries. Many developed countries also have Assisted Voluntary Return (AVR) programmes for asylum seekers who want to go back or were refused asylum.

Third country resettlement

Third country resettlement involves the assisted transfer of refugees from the country in which they have sought asylum to a safe third country that has agreed to admit them as refugees. This can be for permanent settlement or limited to a certain number of years. It is the third durable solution and it can only be considered once the two other solutions have proved impossible.[70][71] The UNHCR has traditionally seen resettlement as the least preferable of the "durable solutions" to refugee situations.[72] However, in April 2000 the then UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Sadako Ogata, stated "Resettlement can no longer be seen as the least-preferred durable solution; in many cases it is the only solution for refugees."[72]

Internally displaced person

UNHCR's mandate has gradually been expanded to include protecting and providing humanitarian assistance to internally displaced persons (IDPs) and people in IDP-like situations. These are civilians who have been forced to flee their homes, but who have not reached a neighboring country. IDPs do not fit the legal definition of a refugee under the 1951 Refugee Convention, 1967 Protocol and the 1969 Organization for African Unity Convention, because they have not left their country. As the nature of war has changed in the last few decades, with more and more internal conflicts replacing interstate wars, the number of IDPs has increased significantly.