A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

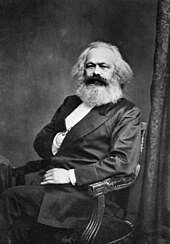

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that originates in the works of 19th century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism analyzes and critiques the development of class society and especially of capitalism as well as the role of class struggles in systemic, economic, social and political change. It frames capitalism through a paradigm of exploitation and analyzes class relations and social conflict using a materialist interpretation of historical development (now known as "historical materialism") – materialist in the sense that the politics and ideas of an epoch are determined by the way in which material production is carried on.[1]

From the late 19th century onward, Marxism has developed from Marx's original revolutionary critique of classical political economy and materialist conception of history into a comprehensive, complete world-view.[1] There are now many different branches and schools of thought, resulting in a discord of the single definitive Marxist theory.[2] Different Marxian schools place a greater emphasis on certain aspects of classical Marxism while rejecting or modifying other aspects. Some schools of thought have sought to combine Marxian concepts and non-Marxian concepts which has then led to contradictory conclusions.[3]

Marxism–Leninism and its offshoots are the most well-known Marxist schools of thought as they were a driving force in international relations during most of the 20th century.[4]

Marxism

Marxism analyzes the material conditions and the economic activities required to fulfill human material needs to explain social phenomena within any given society. It assumes that the form of economic organization, or mode of production, influences all other social phenomena—including wider social relations, political institutions, legal systems, cultural systems, aesthetics, and ideologies. The economic system and these social relations form a base and superstructure. As forces of production improve, existing forms of organizing production become obsolete and hinder further progress. As Karl Marx observed: "At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or—this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms—with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution".[5] These inefficiencies manifest themselves as social contradictions in society which are, in turn, fought out at the level of the class struggle.[6]

Under the capitalist mode of production, this struggle materializes between the minority (the bourgeoisie) who own the means of production and the vast majority of the population (the proletariat) who produce goods and services. Starting with the conjectural premise that social change occurs because of the struggle between different classes within society who are under contradiction against each other, a Marxist would conclude that capitalism exploits and oppresses the proletariat, therefore capitalism will inevitably lead to a proletarian revolution. In a socialist society, private property—in the form of the means of production—would be replaced by co-operative ownership. A socialist economy would not base production on the creation of private profits, but on the criteria of satisfying human needs—that is, production would be carried out directly for use. As Friedrich Engels said: "Then the capitalist mode of appropriation in which the product enslaves first the producer, and then the appropriator, is replaced by the mode of appropriation of the product that is based upon the nature of the modern means of production; upon the one hand, direct social appropriation, as means to the maintenance and extension of production on the other, direct individual appropriation, as means of subsistence and of enjoyment".[7]

Marxian economics and its proponents view capitalism as economically unsustainable and incapable of improving the living standards of the population due to its need to compensate for falling rates of profit by cutting employee's wages, social benefits and pursuing military aggression. The socialist system would succeed capitalism as humanity's mode of production through workers' revolution. According to Marxian crisis theory, socialism is not an inevitability, but an economic necessity.[8]

Classical Marxism is the economic, philosophical and sociological theories expounded by Marx and Engels as contrasted with later developments in Marxism, especially Leninism and Marxism–Leninism.[9] Orthodox Marxism is the body of Marxism thought that emerged after the death of Marx and which became the official philosophy of the socialist movement as represented in the Second International until World War I in 1914. Orthodox Marxism aims to simplify, codify and systematize Marxist method and theory by clarifying the perceived ambiguities and contradictions of classical Marxism. The philosophy of orthodox Marxism includes the understanding that material development (advances in technology in the productive forces) is the primary agent of change in the structure of society and of human social relations and that social systems and their relations (e.g. feudalism, capitalism and so on) become contradictory and inefficient as the productive forces develop, which results in some form of social revolution arising in response to the mounting contradictions. This revolutionary change is the vehicle for fundamental society-wide changes and ultimately leads to the emergence of new economic systems.[10]

As a term, orthodox Marxism represents the methods of historical materialism and of dialectical materialism and not the normative aspects inherent to classical Marxism, without implying dogmatic adherence to the results of Marx's investigations.[11]

Leninism

Leninism is the body of political theory developed by and named after the Russian revolutionary and later Soviet premier Vladimir Lenin for the democratic organisation of a revolutionary vanguard party and the achievement of a dictatorship of the proletariat as political prelude to the establishment of socialism. Leninism comprises socialist political and economic theories developed from Marxism as well as Lenin's interpretations of Marxist theory for practical application to the socio-political conditions of the agrarian early 20th-century Russian Empire. Leninism was the Russian application of Marxist economics and political philosophy, effected and realised by the Bolsheviks, the vanguard party who led the fight for the political independence of the working class. In 1903, Lenin stated:

We want to achieve a new and better order of society: in this new and better society there must be neither rich nor poor; all will have to work. Not a handful of rich people, but all the working people must enjoy the fruits of their common labour. Machines and other improvements must serve to ease the work of all and not to enable a few to grow rich at the expense of millions and tens of millions of people. This new and better society is called socialist society. The teachings about this society are called 'socialism'.[12]

The most important consequence of a Leninist-style theory of imperialism is the strategic need for workers in the industrialized countries to bloc or ally with the oppressed nations contained within their respective countries' colonies abroad to overthrow capitalism. This is the source of the slogan, which shows the Leninist conception that not only the proletariat—as is traditional to Marxism—are the sole revolutionary force, but all oppressed people: "Workers and Oppressed Peoples of the World, Unite!"[13] The other distinguishing characteristic of Leninism is how it approaches the question of organization. Lenin believed that the traditional model of the social democratic parties of the time, a loose, multi-tendency organization, was inadequate for overthrowing the Tsarist regime in Russia. He proposed a cadre of professional revolutionaries that disciplined itself under the model of democratic centralism.[14]

Left communism

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Left communism is the range of communist viewpoints held by the communist left, which criticizes the political ideas of the Bolsheviks from a position that is asserted to be more authentically Marxist and proletarian than the views of Leninism held by the Communist International after its first two congresses.[15]

Although she lived before left communism became a distinct tendency, Rosa Luxemburg has been heavily influential for most left communists, both politically and theoretically. Proponents of left communism have included Herman Gorter, Anton Pannekoek, Otto Rühle, Karl Korsch, Amadeo Bordiga and Paul Mattick.

Prominent left communist groups existing today include the International Communist Current and the Internationalist Communist Tendency. Different factions from the old Bordigist International Communist Party are also considered left communist organizations.

Council communism

Council communism is a movement originating from Germany and the Netherlands in the 1920s. The Communist Workers Party of Germany (KAPD) was the primary organization that espoused council communism. Council communism continues today as a theoretical and activist position within both Marxism and libertarian socialism, through a few groups in Europe and North America.[16] As such, it is referred to as anti-authoritarian and anti-Leninist Marxism.[17]

In contrast to reformist social democracy and to Leninism, the central argument of council communism is that democratic workers councils arising in factories and municipalities are the natural form of working class organisation and governmental power.[18] The government and the economy should be managed by workers' councils[19] composed of delegates elected at workplaces and recallable at any moment. As such, council communists oppose authoritarian socialism, and command economies such as state socialism and state capitalism. They also oppose the idea of a revolutionary party since council communists believe that a party-led revolution will necessarily produce a party dictatorship. This view is also opposed to the social democratic and Marxist–Leninist ideologies, with their stress on parliaments and institutional government (i.e. by applying social reforms) on the one hand[20] and vanguard parties and participative democratic centralism on the other.[18][21] Council communists see the mass strike and new yet to emerge forms of mass action as revolutionary means to achieve a communist society.[22][23] Where the network of worker councils would be the main vehicle for revolution, acting as the apparatus by which the dictatorship of the proletariat forms and operates.[24] Council communism and other types of libertarian Marxism such as autonomism are often viewed as being similar to anarchism due to similar criticisms of Leninist ideologies for being authoritarian and the rejection of the idea of a vanguard party.[18][25]

Trotskyism

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Trotskyism is the branch as advocated by Russian Marxist Leon Trotsky, a contemporary of Lenin from the early years of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, where he led a small trend in competition with both Lenin's Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks. Opposed to Stalinism, Trotskyism supports the theory of permanent revolution and world revolution instead of the two stage theory and socialism in one country. It supported proletarian internationalism and another communist revolution in the Soviet Union which Trotsky claimed had become a degenerated worker's state under the leadership of Stalin in which class relations had re-emerged in a new form, rather than the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Struggling against Stalin for power in the Soviet Union, Trotsky and his supporters organized into the Left Opposition and their platform became known as Trotskyism. Stalin eventually succeeded in gaining control of the Soviet regime and Trotskyist attempts to remove Stalin from power resulted in Trotsky's exile from the Soviet Union in 1929. While in exile, Trotsky continued his campaign against Stalin, founding in 1938 the Fourth International, a Trotskyist rival to the Communist International. In August 1940, Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico City on Stalin's orders.

Trotsky's followers claim to be the heirs of Lenin in the same way that mainstream Marxist–Leninists do. There are several distinguishing characteristics of this school of thought—foremost is the theory of permanent revolution. This stated that in less-developed countries the bourgeoisie were too weak to lead their own bourgeois-democratic revolutions. Due to this weakness, it fell to the proletariat to carry out the bourgeois revolution. With power in its hands, the proletariat would then continue this revolution permanently, transforming it from a national bourgeois revolution to a socialist international revolution.[26]

Another shared characteristic between Trotskyists is a variety of theoretical justifications for their negative appraisal of the post-Lenin Soviet Union after Trotsky was expelled by a majority vote from the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)[27] and subsequently from the Soviet Union. As a consequence, Trotsky defined the Soviet Union under Stalin as a planned economy ruled over by a bureaucratic caste. Trotsky advocated overthrowing the government of the Soviet Union after he was expelled from it.[28]

Marxism–Leninism

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

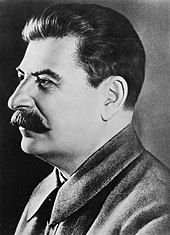

Marxism–Leninism is a political ideology developed by Joseph Stalin which according to its proponents is based in Marxism and Leninism.[29] The term describes the specific political ideology which Stalin implemented in the Soviet Union and in a global scale in the Comintern. There is no definite agreement between historians of about whether Stalin actually followed the principles of Marx and Lenin.[30] It also contains aspects which according to some are deviations from Marxism such as socialism in one country.[31][32]

Marxism–Leninism was the ideology of the most clearly visible communist movement and is the most prominent ideology associated with communism.[4] It refers to the socioeconomic system and political ideology implemented by Stalin in the Soviet Union and later copied by other states based on the Soviet model (central planning, collectivization of agriculture, communist party-led state, rapid industrialization, nationalization of the commanding heights of the economy and the theory of socialism in one country)[33] whereas Stalinism refers to Stalin's style of governance (cult of personality and a totalitarian state).[34][35] Marxism–Leninism was the official state ideology of the Soviet Union and the other ruling parties making up the Eastern Bloc as well as the parties of the Communist International after Bolshevization.[36] Today, Marxism–Leninism is the ideology of several parties around the world and remains the official ideology of the ruling parties of China, Cuba, Laos and Vietnam.[37]

At the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev made several ideological ruptures with his predecessor, Joseph Stalin. First, Khrushchev denounced the cult of personality that had developed around Stalin, although Khrushchev himself had a pivotal role in fostering decades earlier.[38] Khrushchev rejected the heretofore orthodox Marxist–Leninist tenet that class struggle continues even under socialism, but rather the state ought to rule in the name of all classes. A related principle that flowed from the former was the notion of peaceful coexistence, or that the newly emergent socialist bloc could peacefully compete with the capitalist world, solely by developing the productive forces of society. Anti-revisionism is a faction within Marxist–Leninism that rejects Khrushchev's theses. This school of thought holds that Khrushchev was unacceptably altering or revising the fundamental tenets of Marxism–Leninism, a stance from which the label anti-revisionist is derived.[39]

Maoism takes its name from Mao Zedong, the former leader of the People's Republic of China. It is the variety of anti-revisionism that took inspiration and in some cases received material support from China, especially during the Mao period. There are several key concepts that were developed by Mao. First, Mao concurred with Stalin that not only does class struggle continue under the dictatorship of the proletariat, it actually accelerates as long as gains are being made by the proletariat at the expense of the disenfranchised bourgeoisie. Second, Mao developed a strategy for socialist revolution called protracted people's war in what he termed the semi-feudal countries of the Third World and that relied heavily on the peasantry. Third, Mao wrote many theoretical articles on epistemology and dialectics which he called contradictions.

Hoxhaism, so named because of the central contribution of Albanian statesman Enver Hoxha, was closely aligned with China for a number of years, but it grew critical of Maoism because of the so-called Three Worlds Theory put forth by elements within the Chinese Communist Party and because it viewed the actions of Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping unfavorably. However, Hoxhaism as a trend ultimately came to the understanding that socialism had never existed in China at all.

Maoism

Maoism (Chinese: 毛泽东思想; pinyin: Máo Zédōng sīxiǎng; lit. 'Mao Zedong Thought') is the theory that Mao Zedong developed for realising a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China and later the People's Republic of China. The philosophical difference between Maoism and Marxism–Leninism is that the peasantry are the revolutionary vanguard in pre-industrial societies rather than the proletariat. This updating and adaptation of Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions in which revolutionary praxis is primary and ideological orthodoxy is secondary represents urban Marxism–Leninism adapted to pre-industrial China. The claim that Mao had adapted Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions evolved into the idea that he had updated it in a fundamental way applying to the world as a whole.[40][41][42][43][44]

From the 1950s until the Chinese economic reforms of Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s, Maoism was the political and military ideology of the Chinese Communist Party and of Maoist revolutionary movements throughout the world.[45] After the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s, the Chinese Communist Party and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union claimed to be the sole heir and successor to Joseph Stalin concerning the correct interpretation of Marxism–Leninism and ideological leader of world communism.[40]

In the late 1970s, the Peruvian communist party Shining Path developed and synthesized Maoism into Marxism–Leninism–Maoism, a contemporary variety of Marxism–Leninism that is a supposed higher level of Marxism–Leninism that can be applied universally.[46]

Libertarian Marxism

Libertarian Marxism is a broad range of economic and political philosophies that emphasize the anti-authoritarian aspects of Marxism. Early currents of libertarian Marxism, known as left communism,[47] emerged in opposition to Marxism–Leninism[48] and its derivatives, such as Stalinism, Maoism and Trotskyism.[49] Libertarian Marxism is also critical of reformist positions, such as those held by social democrats.[50] Libertarian Marxist currents often draw from Marx and Engels' later works, specifically the Grundrisse and The Civil War in France,[51] emphasizing the Marxist belief in the ability of the working class to forge its own destiny without the need for a revolutionary party or state to mediate or aid its liberation.[52] Along with anarchism, libertarian Marxism is one of the main currents of libertarian socialism.[53]

Libertarian Marxism includes such currents as autonomism, council communism, left communism, Lettrism, Luxemburgism, the Johnson-Forest tendency, the New Left, Situationism, Socialisme ou Barbarie, world socialism and workerism.[54] Libertarian Marxism has often had a strong influence on anarchism, especially post-left and social anarchists. Notable theorists of libertarian Marxism have included Anton Pannekoek, Raya Dunayevskaya, C. L. R. James, Antonio Negri, Cornelius Castoriadis, Maurice Brinton, Guy Debord, Daniel Guérin, Ernesto Screpanti and Raoul Vaneigem.

Western Marxism

Western Marxism is a current of Marxist theory that arose from Western and Central Europe in the aftermath of the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the ascent of Leninism. The term denotes a loose collection of Marxist theorists who emphasised culture, philosophy, and art, in contrast to the Marxism of the Soviet Union.[55]

Key Western Marxists

Georg Lukács

Georg Lukács (13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher and literary critic, who founded Western Marxism with his magnum opus History and Class Consciousness. Written between 1919 and 1922 and first published in 1923, the collection of essays contributed to debates concerning Marxism and its relation to sociology, politics and philosophy. The book also reconstructed aspects of Marx's theory of alienation before the publication of the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, in which Marx most clearly expounds the theory.[56] Lukács's work underlines Marxism's origins in Hegelianism and elaborates Marxist theories such as ideology, false consciousness, reification and class consciousness.

Karl Korsch

Karl Korsch (15 August 1886 – 21 October 1961) was born in Tostedt, near Hamburg, to the family of a middle-ranking bank official.[57] His masterwork Marxism and Philosophy, which attempts to re-establish the historic character of Marxism as the heir to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, earned him condemnation from the Third International.[58] Korsch was especially concerned that Marxist theory was losing its precision and validity—in the words of the day, becoming "vulgarized"—within the upper echelons of the various socialist organizations.

In his later work, he rejected Orthodox Marxism as historically outmoded, wanting to adapt Marxism to a new historical situation. He wrote in his Ten Theses (1950) that "the first step in re-establishing a revolutionary theory and practice consists in breaking with that Marxism which claims to monopolize revolutionary initiative as well as theoretical and practical direction" and that "today, all attempts to re-establish the Marxist doctrine as a whole in its original function as a theory of the working classes social revolution are reactionary utopias".[59]

Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Gramsci (22 January 1891 – 27 April 1937) was an Italian writer, politician and political theorist. He was a founding member and onetime leader of the Communist Party of Italy. He wrote more than 30 notebooks and 3,000 pages of history and analysis during his imprisonment by the Italian Fascist regime. These writings, known as the Prison Notebooks, contain Gramsci's tracing of Italian history and nationalism as well as some ideas in Marxist theory, critical theory and educational theory associated with his name such as:

- Cultural hegemony as a means of maintaining the state in a capitalist society

- The need for popular workers' education to encourage development of intellectuals from the working class

- The distinction between political society (the police, the army, legal system, etc.) which dominates directly and coercively and civil society (the family, the education system, trade unions, etc.) where leadership is constituted through ideology or by means of consent

- "Absolute historicism"

- The critique of economic determinism

- The critique of philosophical materialism

Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse (19 July 1898 – 29 July 1979) was a prominent German-American philosopher and sociologist of Jewish descent and a member of the Frankfurt School.

Marcuse's critiques of capitalist society (especially his 1955 synthesis of Marx and Freud, Eros and Civilization and his 1964 book One-Dimensional Man) resonated with the concerns of the leftist student movement in the 1960s. Because of his willingness to speak at student protests, Marcuse soon became known as "the father of the New Left", a term he disliked and rejected.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre (21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was already a key and influential philosopher and playwright for his early writings on individualistic existentialism. In his later career, Sartre attempted to reconcile the existential philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard with Marxist philosophy and Hegelian dialectics in his work Critique of Dialectical Reason.[60] Sartre was also involved in Marxist politics and was impressed upon visiting Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara, calling him "not only an intellectual but also the most complete human being of our age".[61]

Louis Althusser

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Louis Althusser (16 October 1918 – 22 October 1990) was a Marxist philosopher. He was a longtime member and sometimes strong critic of the French Communist Party. His arguments and theses were set against the threats that he saw attacking the theoretical foundations of Marxism. These included both the influence of empiricism on Marxist theory and humanism and reformist socialist orientations which manifested as divisions in the European Communist parties as well as the problem of the cult of personality and of ideology itself. Althusser is commonly referred to as a structural Marxist, although his relationship to other schools of French structuralism is not a simple affiliation and he is critical of many aspects of structuralism.

His essay Marxism and Humanism is a strong statement of anti-humanism in Marxist theory, condemning ideas like "human potential" and "species-being", which are often put forth by Marxists, as outgrowths of a bourgeois ideology of "humanity". His essay Contradiction and Overdetermination borrows the concept of overdetermination from psychoanalysis to replace the idea of "contradiction" with a more complex model of multiple causality in political situations (an idea closely related to Gramsci's concept of hegemony).

Althusser is also widely known as a theorist of ideology and his best-known essay is Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes Toward an Investigation.[62] The essay establishes the concept of ideology, also based on Gramsci's theory of hegemony. Whereas hegemony is ultimately determined entirely by political forces, ideology draws on Sigmund Freud's and Jacques Lacan's concepts of the unconscious and mirror-phase respectively and describes the structures and systems that allow us to meaningfully have a concept of the self.

Structural Marxism

Structural Marxism is an approach to Marxism based on structuralism, primarily associated with the work of the French theorist Louis Althusser and his students. It was influential in France during the late 1960s and 1970s and also came to influence philosophers, political theorists and sociologists outside France during the 1970s.

Neo-Marxism

Neo-Marxism is a school of Marxism that began in the 20th century and hearkened back to the early writings of Marx before the influence of Friedrich Engels, which focused on dialectical idealism rather than dialectical materialism. It thus rejected economic determinism, being instead far more libertarian. Neo-Marxism adds Max Weber's broader understanding of social inequality, such as status and power, to orthodox Marxist thought.