A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

The history of cartography refers to the development and consequences of cartography, or mapmaking technology, throughout human history. Maps have been one of the most important human inventions for millennia, allowing humans to explain and navigate their way through the world.

When and how the earliest maps were made is unclear, but maps of local terrain are believed to have been independently invented by many cultures. The earliest surviving maps include cave paintings and etchings on tusk and stone. Maps were produced extensively by ancient Babylon, Greece, Rome, China, and India.

The earliest maps ignored the curvature of Earth's surface, both because the shape of the Earth was uncertain and because the curvature is not important across the small areas being mapped. However, since the age of Classical Greece, maps of large regions, and especially of the world, have used projection from a model globe to control how the inevitable distortion gets apportioned on the map.

Modern methods of transportation, the use of surveillance aircraft, and more recently the availability of satellite imagery have made documentation of many areas possible that were previously inaccessible. Free online services such as Google Earth have made accurate maps of the world more accessible than ever before.

Etymology

The English term cartography is modern, borrowed from the French cartographie in the 1840s, itself based on Middle Latin carta "map".

Pre-modern era

Earliest known maps

It is not always clear whether an ancient artifact had been wrought as a map or as something else. The definition of "map" is also not precise. Thus, no single artifact is generally accepted to be the earliest surviving map. Candidates include:

- A map-like representation of a mountain, river, valleys and routes around Pavlov in the Czech Republic, carved on a mammoth tusk, that has been dated to 25,000 BC.[1]

- An Aboriginal Australian cylcon that may be as much as 20,000 years old that is thought to depict the Darling River.[2]

- A map etched on a mammoth bone at Mezhyrich that is about 15,000 years old.

- Dots dating to 14,500 BC found on the walls of the Lascaux caves map of part of the night sky, including the three bright stars Vega, Deneb, and Altair (the Summer Triangle asterism), as well as the Pleiades star cluster. The Cuevas de El Castillo in Spain that contains a dot map of the Corona Borealis constellation dating from 12,000 BC.[3][4][5]

- A polished chunk of sandstone from a cave in Spanish Navarre, dated to 14,000 BC, that may be symbols for landscape features, such as hills or dwellings,[6] superimposed on animal etchings. Alternatively, it may also represent a spiritual landscape, or simple incisings.[7][8]

- Another ancient picture that resembles a map that was created in the late 7th millennium BC in Çatalhöyük, Anatolia, modern Turkey. This wall painting may represent a plan of this Neolithic village;[9] however, recent scholarship has questioned the identification of this painting as a map.[10]

- The "Saint-Bélec slab" (2200–1600 BC), whose lines and symbols have been argued to represent a cadastral plan of a part of western Brittany.[11]

Ancient Near East

Maps in Ancient Babylonia were made by using accurate surveying techniques.[12] For example, a 7.6 × 6.8 cm clay tablet found in 1930 at Ga-Sur, near contemporary Kirkuk, shows a map of a river valley between two hills. Cuneiform inscriptions label the features on the map, including a plot of land described as 354 iku (12 hectares) that was owned by a person called Azala. Most scholars date the tablet to the 25th to 24th century BC. Hills are shown by overlapping semicircles, rivers by lines, and cities by circles. The map also is marked to show the cardinal directions.[13] An engraved map from the Kassite period (14th–12th centuries BC) of Babylonian history shows walls and buildings in the holy city of Nippur.[14]

The Babylonian World Map, the earliest surviving map of the world (c. 600 BC), is a symbolic, not a literal representation. It deliberately omits peoples such as the Persians and Egyptians, who were well known to the Babylonians. The area shown is depicted as a circular shape surrounded by water, which fits the religious image of the world in which the Babylonians believed.

Phoenician sailors made major advances in seafaring and exploration. It is recorded that the first circumnavigation of Africa was possibly undertaken by Phoenician explorers employed by Egyptian pharaoh Necho II c. 610–595 BC.[15][16] In The Histories, written 431–425 BC, Herodotus cast doubt on a report of the Sun observed shining from the north. He stated that the phenomenon was observed by Phoenician explorers during their circumnavigation of Africa (The Histories, 4.42) who claimed to have had the Sun on their right when circumnavigating in a clockwise direction. To modern historians, these details confirm the truth of the Phoenicians' report, and even suggest the possibility that the Phoenicians knew about the spherical Earth model. However, nothing certain about their knowledge of geography and navigation has survived.[15] The historian Dmitri Panchenko theorizes that it was the Phoenician circumnavigation of Africa that inspired the theory of a spherical Earth by the 5th century BC.[16]

Ancient Greece

Many scholars throughout history, such as Strabo, Kish, and Dilke, consider Homer to be the founder of the early Greek conception of Earth, and therefore of geography. Homer conceived Earth to be a disk surrounded by a constantly moving stream of Ocean,[17]: 22 an idea which would be suggested by the appearance of the horizon as it is seen from a mountaintop or from a seacoast. This model was accepted by the early Greeks. Homer and his Greek contemporaries knew very little of the Earth beyond the Libyan desert of Egypt, the southwest coast of Asia Minor, and the northern boundary of the Greek homeland. Furthermore, the coast of the Black Sea was only known through myths and legends that circulated during his time. In his poems there is no mention of Europe and Asia as geographical concepts.[18][full citation needed] That is why the big part of Homer's world that is portrayed on this interpretive map represents lands that border on the Aegean Sea. The Greeks believed that they occupied the central region of Earth and its edges were inhabited by savage, monstrous barbarians and strange animals and monsters: Homer's Odyssey mentions a great many of these.

Additional statements about ancient geography are found in Hesiod's poems, probably written during the 8th century BC.[19] Through the lyrics of Works and Days and Theogony, he shows to his contemporaries some definite geographical knowledge. He introduces the names of such rivers as Nile, Ister (Danube), the shores of the Bosporus and the Euxine (Black Sea), the coast of Gaul, the island of Sicily, and a few other regions and rivers.[20] His advanced geographical knowledge not only had predated Greek colonial expansions, but also was used in the earliest Greek world maps, produced by Greek mapmakers such as Anaximander and Hecataeus of Miletus, and Ptolemy using both observations by explorers and a mathematical approach.

Early steps in the development of intellectual thought in ancient Greece belonged to Ionians from their well-known city of Miletus in Asia Minor. Miletus was placed favourably to absorb aspects of Babylonian knowledge and to profit from the expanding commerce of the Mediterranean. The earliest ancient Greek who is said to have constructed a map of the world is Anaximander of Miletus (c. 611–546 BC), pupil of Thales. He believed that the Earth was a cylindrical form, a stone pillar suspended in space.[21] The inhabited part of his world was circular, disk-shaped, and presumably located on the upper surface of the cylinder.[17]: 24

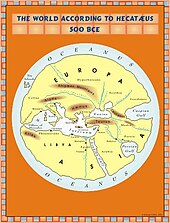

For constructing his world map, Anaximander is considered by many to be the first mapmaker.[22]: 23 Little is known about the map, which has not survived. Hecataeus of Miletus (550–475 BC) produced another map fifty years later that he claimed was an improved version of the map of his illustrious predecessor.

Hecatæus's map describes the Earth as disk with an encircling Ocean, and with Greece placed in the center. This was a very popular contemporary Greek worldview, derived originally from the Homeric poems. Also, similar to many other early maps in antiquity, his map has no scale. As units of measurements, this map used "days of sailing" on the sea and "days of marching" on dry land.[23] The purpose of this map was to accompany Hecatæus's geographical work that was called Periodos Ges, or Journey Round the World.[22]: 24 Periodos Ges was divided into two books, "Europe" and "Asia", with the latter including Libya, the name of which was an ancient term for all of known Africa.

The work divides the world into two continents, Asia and Europe. Hecatæus depicts the line between the Pillars of Hercules through the Bosporus, and the Don River as a boundary between the two. He was the first writer known to have thought that the Caspian flows into the encircling ocean—an idea that persisted long into the Hellenic period. He was particularly instructive about the Black Sea, adding many geographic places that already were known to Greeks through the colonization process. To the north of the Danube, according to Hecatæus, were the Rhipæan (gusty) Mountains, beyond which lived the Hyperboreans—peoples of the far north. Hecatæus depicted the origin of the Nile River at the southern encircling ocean. His view of the Nile seems to have been that it came from the southern encircling ocean. This assumption helped Hecatæus propose a solution to the mystery of the annual flooding of the Nile. He believed that the waves of the ocean were a primary cause of this occurrence.[24] A map based on Hecataeus's was intended to aid political decision-making. According to Herodotus, that map was engraved into a bronze tablet and was carried to Sparta by Aristagoras during the revolt of the Ionian cities against Persian rule from 499 to 494 BC.

Anaximenes of Miletus (6th century BC), who studied under Anaximander, rejected the views of his teacher regarding the shape of the Earth and instead, he visualized the Earth as a rectangular form supported by compressed air.

Pythagoras of Samos (c. 560–480 BC) speculated about the notion of a spherical Earth with a central fire at its core. He is sometimes incorrectly credited with the introduction of a model that divides a spherical Earth into five zones: one hot, two temperate, and two cold—northern and southern. This idea, known as the zonal theory of climate, is more likely to have originated at the time of Aristotle.[25]

Scylax, a sailor, made a record of his Mediterranean voyages in c. 515 BC. This is the earliest known set of Greek periploi, or sailing instructions, which became the basis for many future mapmakers, especially in the medieval period.[26]

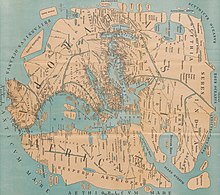

The way in which the geographical knowledge of the Greeks advanced from the previous assumptions of the Earth's shape was through Herodotus and his conceptual view of the world. This map also did not survive and many have speculated that it was never produced. A possible reconstruction of his map is displayed below.

Herodotus traveled extensively, collecting information and documenting his findings in his books on Europe, Asia, and Libya. He also combined his knowledge with what he learned from the people he met. Herodotus wrote his Histories in the mid-5th century BC. Although his work was dedicated to the story of long struggle of the Greeks with the Persian Empire, Herodotus also included everything he knew about the geography, history, and peoples of the world. Thus, his work provides a detailed picture of the known world of the 5th century BC.

Herodotus rejected the prevailing view of most 5th-century BC maps that the Earth is a disk surrounded by ocean. In his work he describes the Earth as an irregular shape with oceans surrounding only Asia and Africa. He introduces names such as the Atlantic Sea, and the Erythrean Sea, which translates as the "Red Sea". He also divided the world into three continents: Europe, Asia, and Africa. He depicted the boundary of Europe as the line from the Pillars of Hercules through the Bosphorus and the area between the Caspian Sea and the Indus River. He regarded the Nile as the boundary between Asia and Africa. He speculated that the extent of Europe was much greater than was assumed at the time and left Europe's shape to be determined by future research.

In the case of Africa, he believed that, except for the small stretch of land in the vicinity of Suez, the continent was in fact surrounded by water. However, he definitely disagreed with his predecessors and contemporaries about its presumed circular shape. He based his theory on the story of Pharaoh Necho II, the ruler of Egypt between 609 and 594 BC, who had sent Phoenicians to circumnavigate Africa. Apparently, it took them three years, but they certainly did prove his idea. He speculated that the Nile River started as far west as the Ister River (Danube) in Europe and cut Africa through the middle. He was the first writer to assume that the Caspian Sea was separated from other seas and he recognised northern Scythia as one of the coldest inhabited lands in the world.

Similar to his predecessors, Herodotus also made mistakes. He accepted a clear distinction between the civilized Greeks in the center of the Earth and the barbarians on the world's edges. In his Histories it is clear that he believed that the world became stranger and stranger when one traveled away from Greece, until one reached the ends of the Earth, where humans behaved as savages.

While various previous Greek philosophers presumed the Earth to be spherical, Aristotle (384–322 BC) is credited with proving the Earth's sphericity. His arguments may be summarized as follows:

- The lunar eclipse is always circular

- Ships seem to sink as they move away from view and pass the horizon

- Some stars can be seen only from certain parts of the Earth.

Hellenistic Mediterranean

A vital contribution to mapping the reality of the world came with a scientific estimate of the circumference of the earth. This event has been described as the first scientific attempt to give geographical studies a mathematical basis. The man credited for this achievement was Eratosthenes (275–195 BC), a Greek scholar who lived in Hellenistic North Africa. As described by George Sarton, historian of science, "there was among them a man of genius but as he was working in a new field they were too stupid to recognize him".[27] His work, including On the Measurement of the Earth and Geographica, has only survived in the writings of later philosophers such as Cleomedes and Strabo. He was a devoted geographer who set out to reform and perfect the map of the world. Eratosthenes argued that accurate mapping, even if in two dimensions only, depends upon the establishment of accurate linear measurements. He was the first to calculate the Earth's circumference (within 0.5 percent accuracy).[28] His great achievement in the field of cartography was the use of a new technique of charting with meridians, his imaginary north–south lines, and parallels, his imaginary west–east lines.[29] These axis lines were placed over the map of the Earth with their origin in the city of Rhodes and divided the world into sectors. Then, Eratosthenes used these earth partitions to reference places on the map. He also divided Earth into five climatic regions which was proposed at least as early as the late sixth or early fifth century BC by Parmenides: a torrid zone across the middle, two frigid zones at extreme north and south, and two temperate bands in between.[30] He was likely also the first person to use the word "geography".[31]

Roman Empire

Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela is unique among ancient geographers in that, after dividing the earth into five zones, of which two only were habitable, he asserts the existence of antichthones, inhabiting the southern temperate zone inaccessible to the folk of the northern temperate regions from the unbearable heat of the intervening torrid belt. On the divisions and boundaries of Europe, Asia and Africa, he repeats Eratosthenes; like all classical geographers from Alexander the Great (except Ptolemy) he regards the Caspian Sea as an inlet of the Northern Ocean, corresponding to the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea on the south.

Marinus of Tyre

Marinus of Tyre was a Hellenized Phoenician geographer and cartographer.[32] He founded mathematical geography and provided the underpinnings of Ptolemy's influential Geographia.

Marinus's geographical treatise is lost and known only from Ptolemy's remarks. He introduced improvements to the construction of maps and developed a system of nautical charts. His chief legacy is that he first assigned to each place a proper latitude and longitude. His zero meridian ran through the westernmost land known to him, the Isles of the Blessed around the location of the Canary or Cape Verde Islands. He used the parallel of Rhodes for measurements of latitude. Ptolemy mentions several revisions of Marinus's geographical work, which is often dated to AD 114 although this is uncertain. Marinus estimated a length of 180,000 stadia for the equator, roughly corresponding[a] to a circumference of the Earth of 33,300 km, about 17% less than the actual value.

He also carefully studied the works of his predecessors and the diaries of travelers. His maps were the first in the Roman Empire to show China. He also invented equirectangular projection, which is still used in map creation today. A few of Marinus's opinions are reported by Ptolemy. Marinus was of the opinion that the World Ocean was separated into an eastern and a western part by the continents of Europe, Asia and Africa. He thought that the inhabited world stretched in latitude from Thule (Norway) to Agisymba (around the Tropic of Capricorn) and in longitude from the Isles of the Blessed (around the Canaries) to Shera (China). Marinus also coined the term Antarctic, referring to the opposite of the Arctic Circle.

Ptolemy

Ptolemy (90–168), a Hellenized Egyptian,[33][34][35] thought that, with the aid of astronomy and mathematics, the Earth could be mapped very accurately. Ptolemy revolutionized the depiction of the spherical Earth on a map by using perspective projection, and suggested precise methods for fixing the position of geographic features on its surface using a coordinate system with parallels of latitude and meridians of longitude.[6][36]

Ptolemy's eight-volume atlas Geographia is a prototype of modern mapping and GIS. It included an index of place-names, with the latitude and longitude of each place to guide the search, scale, conventional signs with legends, and the practice of orienting maps so that north is at the top and east to the right of the map—an almost universal custom today.

Yet with all his important innovations, however, Ptolemy was not infallible. His most important error was a miscalculation of the circumference of the Earth. He believed that Eurasia covered 180° of the globe, which convinced Christopher Columbus to sail across the Atlantic to look for a simpler and faster way to travel to India. Had Columbus known that the true figure was much greater, it is conceivable that he would never have set out on his momentous voyage.

Tabula Peutingeriana

In 2007, the Tabula Peutingeriana, a 12th-century replica of a 5th-century road map, was placed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register and displayed to the public for the first time. Although the scroll is well preserved and believed to be an accurate copy of an authentic original, it is on media that is now so delicate that it must be protected at all times from exposure to daylight.[37]

China

The earliest known maps to have survived in China date to the 4th century BC.[38]: 90 In 1986, seven ancient Chinese maps were found in an archeological excavation of a Qin State tomb in what is now Fangmatan, in the vicinity of Tianshui City, Gansu.[38]: 90 Before this find, the earliest extant maps that were known came from the Mawangdui Han tomb excavation in 1973, which found three maps on silk dated to the 2nd century BC in the early Han dynasty.[38]: 90, 93 The 4th-century BC maps from the State of Qin were drawn with black ink on wooden blocks.[38]: 91 These blocks fortunately survived in soaking conditions due to underground water that had seeped into the tomb; the quality of the wood had much to do with their survival.[38]: 91 After two years of slow-drying techniques, the maps were fully restored.[38]: 91

The territory shown in the seven Qin maps overlap each other.[38]: 92 The maps display tributary river systems of the Jialing River in Sichuan, in a total measured area of 107 by 68 km.[38]: 92 The maps featured rectangular symbols encasing character names for the locations of administrative counties.[38]: 92 Rivers and roads are displayed with similar line symbols; this makes interpreting the map somewhat difficult, although the labels of rivers placed in order of stream flow are helpful to modern day cartographers.[38]: 92–93 These maps also feature locations where different types of timber can be gathered, while two of the maps state the distances in mileage to the timber sites.[38]: 93 In light of this, these maps are perhaps the oldest economic maps in the world since they predate Strabo's economic maps.[38]: 93

In addition to the seven maps on wooden blocks found at Tomb 1 of Fangmatan, a fragment of a paper map was found on the chest of the occupant of Tomb 5 of Fangmatan in 1986. This tomb is dated to the early Western Han, so the map dates to the early 2nd century BC. The map shows topographic features such as mountains, waterways and roads, and is thought to cover the area of the preceding Qin Kingdom.[39][40]

Earliest geographical writing

In China, the earliest known geographical Chinese writing dates back to the 5th century BC, during the beginning of the Warring States (481–221 BC).[41]: 500 This was the Yu Gong or Tribute of Yu chapter of the Shu Jing or Book of Documents. The book describes the traditional nine provinces, their kinds of soil, their characteristic products and economic goods, their tributary goods, their trades and vocations, their state revenues and agricultural systems, and the various rivers and lakes listed and placed accordingly.[41]: 500 The nine provinces in the time of this geographical work were very small in size compared to their modern Chinese counterparts. The Yu Gong's descriptions pertain to areas of the Yellow River, the lower valleys of the Yangzi, with the plain between them and the Shandong Peninsula, and to the west the most northern parts of the Wei River and the Han River were known (along with the southern parts of modern-day Shanxi).[41]: 500

Earliest known reference to a map (圖 tú)

The oldest reference to a map in China comes from the 3rd century BC.[41]: 534 This was the event of 227 BC where Crown Prince Dan of Yan had his assassin Jing Ke visit the court of the ruler of the State of Qin, who would become the first leader to unify China, Qin Shi Huang (r. 221–210 BC). Jing Ke was to present the ruler of Qin with a district map painted on a silk scroll, rolled up and held in a case where he hid his assassin's dagger.[41]: 534 Handing to him the map of the designated territory was the first diplomatic act of submitting that district to Qin rule.[41]: 534 Jing then tried and failed to kill him. From then on, maps were frequently mentioned in Chinese sources.[41]: 535

Han dynasty

The three Han dynasty maps found at Mawangdui differ from the earlier Qin State maps. While the Qin maps place the cardinal direction of north at the top of the map, the Han maps are orientated with the southern direction at the top.[38]: 93 The Han maps are also more complex, since they cover a much larger area, employ a large number of well-designed map symbols, and include additional information on local military sites and the local population.[38]: 93 The Han maps also note measured distances between certain places, but a formal graduated scale and rectangular grid system for maps would not be used—or at least described in full—until the 3rd century (see Pei Xiu below).[38]: 93–94 Among the three maps found at Mawangdui was a small map representing the tomb area where it was found, a larger topographical map showing the Han's borders along the subordinate Kingdom of Changsha and the Nanyue kingdom (of northern Vietnam and parts of modern Guangdong and Guangxi), and a map which marks the positions of Han military garrisons that were employed in an attack against Nanyue in 181 BC.[42]

An early text that mentioned maps was the Rites of Zhou.[41]: 534 Although attributed to the era of the Zhou dynasty, its first recorded appearance was in the libraries of Prince Liu De (c. 130 BC), and was compiled and commented on by Liu Xin in the 1st century AD. It outlined the use of maps that were made for governmental provinces and districts, principalities, frontier boundaries, and even pinpointed locations of ores and minerals for mining facilities.[41]: 534 Upon the investiture of three of his sons as feudal princes in 117 BC, Emperor Wu of Han had maps of the entire empire submitted to him.[41]: 536

From the 1st century AD onwards, official Chinese historical texts contained a geographical section (地理纪; Diliji), which was often an enormous compilation of changes in place-names and local administrative divisions controlled by the ruling dynasty, descriptions of mountain ranges, river systems, taxable products, etc.[41]: 508 From the 5th century BC Shu Jing forward, Chinese geographical writing provided more concrete information and less legendary element. This example can be seen in the 4th chapter of the Huainanzi (Book of the Master of Huainan), compiled under the editorship of Prince Liu An in 139 BC during the Han dynasty (202 BC–202 AD). The chapter gave general descriptions of topography in a systematic fashion, given visual aids by the use of maps (di tu) due to the efforts of Liu An and his associate Zuo Wu.[41]: 507–508 In Chang Chu's Hua Yang Guo Chi ("Historical Geography of Sichuan") of 347, not only rivers, trade routes, and various tribes were described, but it also wrote of a 'Ba June Tu Jing' ("Map of Sichuan"), which had been made much earlier in 150.[41]: 517

Local mapmaking such as the one of Sichuan mentioned above, became a widespread tradition of Chinese geographical works by the 6th century, as noted in the bibliography of the Sui Shu.[41]: 518 It is during this time of the Southern and Northern Dynasties that the Liang dynasty (502–557) cartographers also began carving maps into stone steles (alongside the maps already drawn and painted on paper and silk).[41]: 543

Pei Xiu, the 'Ptolemy of China'

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Golden_Age_of_Dutch_cartographyText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk