A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Czech | |

|---|---|

| čeština, český jazyk | |

| Native to | Czech Republic |

| Ethnicity | Czechs |

Native speakers | 10.7 million (2015)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Institute of the Czech Language (of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | cs |

| ISO 639-2 | cze (B) ces (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | ces |

| Glottolog | czec1258 |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-da < 53-AAA-b...-d |

| IETF | cs[4] |

Czech (/tʃɛk/; endonym: čeština [ˈtʃɛʃcɪna]), historically also known as Bohemian[5] (/boʊˈhiːmiən, bə-/;[6] Latin: lingua Bohemica), is a West Slavic language of the Czech–Slovak group, written in Latin script.[5] Spoken by over 10 million people, it serves as the official language of the Czech Republic. Czech is closely related to Slovak, to the point of high mutual intelligibility, as well as to Polish to a lesser degree.[7] Czech is a fusional language with a rich system of morphology and relatively flexible word order. Its vocabulary has been extensively influenced by Latin and German.

The Czech–Slovak group developed within West Slavic in the high medieval period, and the standardization of Czech and Slovak within the Czech–Slovak dialect continuum emerged in the early modern period. In the later 18th to mid-19th century, the modern written standard became codified in the context of the Czech National Revival. The most widely spoken non-standard variety, known as Common Czech, is based on the vernacular of Prague, but is now spoken as an interdialect throughout most of Bohemia. The dialects spoken in Moravia are considerably more varied than the dialects of Bohemia.[8] A popular misconception holds that eastern Moravian dialects are closer to Slovak than Czech, but this is incorrect; in fact, the opposite is true, and certain dialects in far western Slovakia exhibit features more akin to standard Czech than to standard Slovak.[8]

Czech has a moderately-sized phoneme inventory, comprising ten monophthongs, three diphthongs and 25 consonants (divided into "hard", "neutral" and "soft" categories). Words may contain complicated consonant clusters or lack vowels altogether. Czech has a raised alveolar trill, which is known to occur as a phoneme in only a few other languages, represented by the grapheme ř.

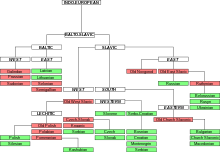

Classification

Czech is a member of the West Slavic sub-branch of the Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family. This branch includes Polish, Kashubian, Upper and Lower Sorbian and Slovak. Slovak is the most closely related language to Czech, followed by Polish and Silesian.[9]

The West Slavic languages are spoken in Central Europe. Czech is distinguished from other West Slavic languages by a more-restricted distinction between "hard" and "soft" consonants (see Phonology below).[9]

History

Medieval/Old Czech

The term "Old Czech" is applied to the period predating the 16th century, with the earliest records of the high medieval period also classified as "early Old Czech", but the term "Medieval Czech" is also used. The function of the written language was initially performed by Old Slavonic written in Glagolitic, later by Latin written in Latin script.

Around the 7th century, the Slavic expansion reached Central Europe, settling on the eastern fringes of the Frankish Empire. The West Slavic polity of Great Moravia formed by the 9th century. The Christianization of Bohemia took place during the 9th and 10th centuries. The diversification of the Czech-Slovak group within West Slavic began around that time, marked among other things by its use of the voiced velar fricative consonant (/ɣ/)[10] and consistent stress on the first syllable.[11]

The Bohemian (Czech) language is first recorded in writing in glosses and short notes during the 12th to 13th centuries. Literary works written in Czech appear in the late 13th and early 14th century and administrative documents first appear towards the late 14th century. The first complete Bible translation, the Leskovec-Dresden Bible, also dates to this period.[12] Old Czech texts, including poetry and cookbooks, were also produced outside universities.[13]

Literary activity becomes widespread in the early 15th century in the context of the Bohemian Reformation. Jan Hus contributed significantly to the standardization of Czech orthography, advocated for widespread literacy among Czech commoners (particularly in religion) and made early efforts to model written Czech after the spoken language.[12]

Early Modern Czech

There was no standardization distinguishing between Czech and Slovak prior to the 15th century. In the 16th century, the division between Czech and Slovak becomes apparent, marking the confessional division between Lutheran Protestants in Slovakia using Czech orthography and Catholics, especially Slovak Jesuits, beginning to use a separate Slovak orthography based on Western Slovak dialects.[14][15]

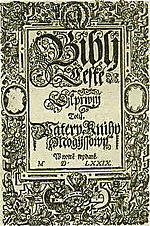

The publication of the Kralice Bible between 1579 and 1593 (the first complete Czech translation of the Bible from the original languages) became very important for standardization of the Czech language in the following centuries as it was used as a model for the standard language.[16]

In 1615, the Bohemian diet tried to declare Czech to be the only official language of the kingdom. After the Bohemian Revolt (of predominantly Protestant aristocracy) which was defeated by the Habsburgs in 1620, the Protestant intellectuals had to leave the country. This emigration together with other consequences of the Thirty Years' War had a negative impact on the further use of the Czech language. In 1627, Czech and German became official languages of the Kingdom of Bohemia and in the 18th century German became dominant in Bohemia and Moravia, especially among the upper classes.[17]

Modern Czech

The modern standard Czech language originates in standardization efforts of the 18th century.[18] By then the language had developed a literary tradition, and since then it has changed little; journals from that period have no substantial differences from modern standard Czech, and contemporary Czechs can understand them with little difficulty.[19] Sometime before the 18th century, the Czech language abandoned a distinction between phonemic /l/ and /ʎ/ which survives in Slovak.[20]

With the beginning of the national revival of the mid-18th century, Czech historians began to emphasize their people's accomplishments from the 15th through the 17th centuries, rebelling against the Counter-Reformation (the Habsburg re-catholization efforts which had denigrated Czech and other non-Latin languages).[21] Czech philologists studied sixteenth-century texts, advocating the return of the language to high culture.[22] This period is known as the Czech National Revival[23] (or Renaissance).[22]

During the national revival, in 1809 linguist and historian Josef Dobrovský released a German-language grammar of Old Czech entitled Ausführliches Lehrgebäude der böhmischen Sprache ('Comprehensive Doctrine of the Bohemian Language'). Dobrovský had intended his book to be descriptive, and did not think Czech had a realistic chance of returning as a major language. However, Josef Jungmann and other revivalists used Dobrovský's book to advocate for a Czech linguistic revival.[23] Changes during this time included spelling reform (notably, í in place of the former j and j in place of g), the use of t (rather than ti) to end infinitive verbs and the non-capitalization of nouns (which had been a late borrowing from German).[20] These changes differentiated Czech from Slovak.[24] Modern scholars disagree about whether the conservative revivalists were motivated by nationalism or considered contemporary spoken Czech unsuitable for formal, widespread use.[23]

Adherence to historical patterns was later relaxed and standard Czech adopted a number of features from Common Czech (a widespread, informally used interdialectal variety), such as leaving some proper nouns undeclined. This has resulted in a relatively high level of homogeneity among all varieties of the language.[25]

Geographic distribution

Czech is spoken by about 10 million residents of the Czech Republic.[17][26] A Eurobarometer survey conducted from January to March 2012 found that the first language of 98 percent of Czech citizens was Czech, the third-highest proportion of a population in the European Union (behind Greece and Hungary).[27]

As the official language of the Czech Republic (a member of the European Union since 2004), Czech is one of the EU's official languages and the 2012 Eurobarometer survey found that Czech was the foreign language most often used in Slovakia.[27] Economist Jonathan van Parys collected data on language knowledge in Europe for the 2012 European Day of Languages. The five countries with the greatest use of Czech were the Czech Republic (98.77 percent), Slovakia (24.86 percent), Portugal (1.93 percent), Poland (0.98 percent) and Germany (0.47 percent).[28]

Czech speakers in Slovakia primarily live in cities. Since it is a recognized minority language in Slovakia, Slovak citizens who speak only Czech may communicate with the government in their language to the extent that Slovak speakers in the Czech Republic may do so.[29]

United States

Immigration of Czechs from Europe to the United States occurred primarily from 1848 to 1914. Czech is a Less Commonly Taught Language in U.S. schools, and is taught at Czech heritage centers. Large communities of Czech Americans live in the states of Texas, Nebraska and Wisconsin.[30] In the 2000 United States Census, Czech was reported as the commonest language spoken at home (besides English) in Valley, Butler and Saunders Counties, Nebraska and Republic County, Kansas. With the exception of Spanish (the non-English language most commonly spoken at home nationwide), Czech was the most common home language in more than a dozen additional counties in Nebraska, Kansas, Texas, North Dakota and Minnesota.[31] As of 2009,[update] 70,500 Americans spoke Czech as their first language (49th place nationwide, after Turkish and before Swedish).[32]

Phonology

Vowels

Standard Czech contains ten basic vowel phonemes, and three diphthongs. The vowels are /a/, /ɛ/, /ɪ/, /o/, and /u/, and their long counterparts /aː/, /ɛː/, /iː/, /oː/ and /uː/. The diphthongs are /ou̯/, /au̯/ and /ɛu̯/; the last two are found only in loanwords such as auto "car" and euro "euro".[33]

In Czech orthography, the vowels are spelled as follows:

- Short: a, e/ě, i/y, o, u

- Long: á, é, í/ý, ó, ú/ů

- Diphthongs: ou, au, eu

The letter ⟨ě⟩ indicates that the previous consonant is palatalized (e.g. něco /ɲɛt͡so/). After a labial it represents /jɛ/ (e.g. běs /bjɛs/); but ⟨mě⟩ is pronounced /mɲɛ/, cf. měkký (/mɲɛkiː/).[34]

Consonants

The consonant phonemes of Czech and their equivalent letters in Czech orthography are as follows:[35]

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ɲ ⟨ň⟩ | ||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | c ⟨ť⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | ||

| voiced | b ⟨b⟩ | d ⟨d⟩ | ɟ ⟨ď⟩ | (ɡ) ⟨g⟩ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s ⟨c⟩ | t͡ʃ ⟨č⟩ | ||||

| voiced | (d͡z) | (d͡ʒ) | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨š⟩ | x ⟨ch⟩ | ||

| voiced | v ⟨v⟩ | z ⟨z⟩ | ʒ ⟨ž⟩ | ɦ ⟨h⟩ | |||

| Trill | plain | r ⟨r⟩ | |||||

| fricative | r̝ ⟨ř⟩ | ||||||

| Approximant | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨j⟩ | |||||

Czech consonants are categorized as "hard", "neutral", or "soft":

- Hard: /d/, /ɡ/, /ɦ/, /k/, /n/, /r/, /t/, /x/

- Neutral: /b/, /f/, /l/, /m/, /p/, /s/, /v/, /z/

- Soft: /c/, /ɟ/, /j/, /ɲ/, /r̝/, /ʃ/, /t͡s/, /t͡ʃ/, /ʒ/

Hard consonants may not be followed by i or í in writing, or soft ones by y or ý (except in loanwords such as kilogram).[36] Neutral consonants may take either character. Hard consonants are sometimes known as "strong", and soft ones as "weak".[37] This distinction is also relevant to the declension patterns of nouns, which vary according to whether the final consonant of the noun stem is hard or soft.[38]

Voiced consonants with unvoiced counterparts are unvoiced at the end of a word before a pause, and in consonant clusters voicing assimilation occurs, which matches voicing to the following consonant. The unvoiced counterpart of /ɦ/ is /x/.[39]

The phoneme represented by the letter ř (capital Ř) is very rare among languages and often claimed to be unique to Czech, though it also occurs in some dialects of Kashubian, and formerly occurred in Polish.[40] It represents the raised alveolar non-sonorant trill (IPA: ), a sound somewhere between Czech r and ž (example: ⓘ),[41] and is present in Dvořák. In unvoiced environments, /r̝/ is realized as its voiceless allophone , a sound somewhere between Czech r and š.[42]

The consonants /r/, /l/, and /m/ can be syllabic, acting as syllable nuclei in place of a vowel. Strč prst skrz krk ("Stick finger through throat") is a well-known Czech tongue twister using syllabic consonants but no vowels.[43]

Stress

Each word has primary stress on its first syllable, except for enclitics (minor, monosyllabic, unstressed syllables). In all words of more than two syllables, every odd-numbered syllable receives secondary stress. Stress is unrelated to vowel length; both long and short vowels can be stressed or unstressed.[44] Vowels are never reduced in tone (e.g. to schwa sounds) when unstressed.[45] When a noun is preceded by a monosyllabic preposition, the stress usually moves to the preposition, e.g. do Prahy "to Prague".[46]

Grammar

Czech grammar, like that of other Slavic languages, is fusional; its nouns, verbs, and adjectives are inflected by phonological processes to modify their meanings and grammatical functions, and the easily separable affixes characteristic of agglutinative languages are limited.[47] Czech inflects for case, gender and number in nouns and tense, aspect, mood, person and subject number and gender in verbs.[48]

Parts of speech include adjectives, adverbs, numbers, interrogative words, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections.[49] Adverbs are primarily formed from adjectives by taking the final ý or í of the base form and replacing it with e, ě, y, or o.[50] Negative statements are formed by adding the affix ne- to the main verb of a clause,[51] with one exception: je (he, she or it is) becomes není.[52]

Sentence and clause structure

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | já | my |

| 2. | ty vy (formal) |

vy |

| 3. | on (masculine) ona (feminine) ono (neuter) |

oni (masculine animate) ony (masculine inanimate, feminine) ona (neuter) |

Because Czech uses grammatical case to convey word function in a sentence (instead of relying on word order, as English does), its word order is flexible. As a pro-drop language, in Czech an intransitive sentence can consist of only a verb; information about its subject is encoded in the verb.[53] Enclitics (primarily auxiliary verbs and pronouns) appear in the second syntactic slot of a sentence, after the first stressed unit. The first slot can contain a subject or object, a main form of a verb, an adverb, or a conjunction (except for the light conjunctions a, "and", i, "and even" or ale, "but").[54]

Czech syntax has a subject–verb–object sentence structure. In practice, however, word order is flexible and used to distinguish topic and focus, with the topic or theme (known referents) preceding the focus or rheme (new information) in a sentence; Czech has therefore been described as a topic-prominent language.[55] Although Czech has a periphrastic passive construction (like English), in colloquial style, word-order changes frequently replace the passive voice. For example, to change "Peter killed Paul" to "Paul was killed by Peter" the order of subject and object is inverted: Petr zabil Pavla ("Peter killed Paul") becomes "Paul, Peter killed" (Pavla zabil Petr). Pavla is in the accusative case, the grammatical object of the verb.[56]

A word at the end of a clause is typically emphasized, unless an upward intonation indicates that the sentence is a question:[57]

- Pes jí bagetu. – The dog eats the baguette (rather than eating something else).

- Bagetu jí pes. – The dog eats the baguette (rather than someone else doing so).

- Pes bagetu jí. – The dog eats the baguette (rather than doing something else to it).

- Jí pes bagetu? – Does the dog eat the baguette? (emphasis ambiguous)

In parts of Bohemia (including Prague), questions such as Jí pes bagetu? without an interrogative word (such as co, "what" or kdo, "who") are intoned in a slow rise from low to high, quickly dropping to low on the last word or phrase.[58]

In modern Czech syntax, adjectives precede nouns,[59] with few exceptions.[60] Relative clauses are introduced by relativizers such as the adjective který, analogous to the English relative pronouns "which", "that" and "who"/"whom". As with other adjectives, it agrees with its associated noun in gender, number and case. Relative clauses follow the noun they modify. The following is a glossed example:[61]

Chc-i

want-1SG

navštív-it

visit-INF

universit-u,

university-SG.ACC,

na

on

kter-ou

which-SG.F.ACC

chod-í

attend-3SG

Jan.

John.SG.NOM

I want to visit the university that John attends.

Declension

In Czech, nouns and adjectives are declined into one of seven grammatical cases which indicate their function in a sentence, two numbers (singular and plural) and three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter). The masculine gender is further divided into animate and inanimate classes.

Case

A nominative–accusative language, Czech marks subject nouns of transitive and intransitive verbs in the nominative case, which is the form found in dictionaries, and direct objects of transitive verbs are declined in the accusative case.[62] The vocative case is used to address people.[63] The remaining cases (genitive, dative, locative and instrumental) indicate semantic relationships, such as noun adjuncts (genitive), indirect objects (dative), or agents in passive constructions (instrumental).[64] Additionally prepositions and some verbs require their complements to be declined in a certain case.[62] The locative case is only used after prepositions.[65] An adjective's case agrees with that of the noun it modifies. When Czech children learn their language's declension patterns, the cases are referred to by number:[66]

| No. | Ordinal name (Czech) | Full name (Czech) | Case | Main usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | první pád | nominativ | nominative | Subjects |

| 2. | druhý pád | genitiv | genitive | Noun adjuncts, possession, prepositions of motion, time and location |

| 3. | třetí pád | dativ | dative | Indirect objects, prepositions of motion |

| 4. | čtvrtý pád | akuzativ | accusative | Direct objects, prepositions of motion and time |

| 5. | pátý pád | vokativ | vocative | Addressing someone |

| 6. | šestý pád | lokál | locative | Prepositions of location, time and topic |

| 7. | sedmý pád | instrumentál | instrumental | Passive agents, instruments, prepositions of location |

Some prepositions require the nouns they modify to take a particular case. The cases assigned by each preposition are based on the physical (or metaphorical) direction, or location, conveyed by it. For example, od (from, away from) and z (out of, off) assign the genitive case. Other prepositions take one of several cases, with their meaning dependent on the case; na means "onto" or "for" with the accusative case, but "on" with the locative.[67]

This is a glossed example of a sentence using several cases:

Nes-l

carry-SG.M.PST

js-em

be-1.SG

krabic-i

box-SG.ACC

do

into

dom-u

house-SG.GEN

se

with

sv-ým

own-SG.INS

přítel-em.

friend-SG.INS

I carried the box into the house with my friend.

Gender

Czech distinguishes three genders—masculine, feminine, and neuter—and the masculine gender is subdivided into animate and inanimate. With few exceptions, feminine nouns in the nominative case end in -a, -e, or a consonant; neuter nouns in -o, -e, or -í, and masculine nouns in a consonant.[68] Adjectives, participles, most pronouns, and the numbers "one" and "two" are marked for gender and agree with the gender of the noun they modify or refer to.[69] Past tense verbs are also marked for gender, agreeing with the gender of the subject, e.g. dělal (he did, or made); dělala (she did, or made) and dělalo (it did, or made).[70] Gender also plays a semantic role; most nouns that describe people and animals, including personal names, have separate masculine and feminine forms which are normally formed by adding a suffix to the stem, for example Čech (Czech man) has the feminine form Češka (Czech woman).[71]

Nouns of different genders follow different declension patterns. Examples of declension patterns for noun phrases of various genders follow:

| Case | Noun/adjective | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big dog (m. anim. sg.) | Black backpack (m. inanim. sg.) | Small cat (f. sg.) | Hard wood (n. sg.) | |

| Nom. | velký pes (big dog) |

černý batoh (black backpack) |

malá kočka (small cat) |

tvrdé dřevo (hard wood) |

| Gen. | bez velkého psa (without the big dog) |

bez černého batohu (without the black backpack) |

bez malé kočky (without the small cat) |

bez tvrdého dřeva (without the hard wood) |

| Dat. | k velkému psovi (to the big dog) |

k černému batohu (to the black backpack) |

k malé kočce (to the small cat) |

ke tvrdému dřevu (to the hard wood) |

| Acc. | vidím velkého psa (I see the big dog) |

vidím černý batoh (I see the black backpack) |

vidím malou kočku (I see the small cat) |

vidím tvrdé dřevo (I see the hard wood) |

| Voc. | velký pse! (big dog!) |

černý batohu! (black backpack!) |

malá kočko! (small cat!) |

tvrdé dřevo! (hard wood!) |

| Loc. | o velkém psovi (about the big dog) |

o černém batohu (about the black backpack) |

o malé kočce (about the small cat) |

o tvrdém dřevě (about the hard wood) |