A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Zürich | |

|---|---|

From top to bottom: View over Zürich from the Grossmünster, the Opera House, Prime Tower at night, ETH main building and Fraumünster church in the old town. | |

|

| |

| Coordinates: 47°22′28″N 08°32′28″E / 47.37444°N 8.54111°E | |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Canton | Zürich |

| District | Zürich |

| Government | |

| • Executive | Stadtrat with 9 members |

| • Mayor | Stadtpräsidentin (list) Corine Mauch SPS/PSS (as of February 2014) |

| • Parliament | Gemeinderat with 125 members |

| Area | |

| • Total | 87.88 km2 (33.93 sq mi) |

| Elevation (Zürich Hauptbahnhof) | 408 m (1,339 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 871 m (2,858 ft) |

| Lowest elevation (Limmat) | 392 m (1,286 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 415,367 |

| • Density | 4,700/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym | German: Zürcher(in) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (Central European Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (Central European Summer Time) |

| Postal code(s) | 8000–8099 |

| SFOS number | 0261 |

| ISO 3166 code | CH-ZH |

| Surrounded by | Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon |

| Twin towns | Kunming, San Francisco |

| Website | stadt-zuerich SFSO statistics |

Zürich (/ˈzjʊərɪk/ ZURE-ik, German: [ˈtsyːrɪç] ; see below) is the largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zürich. It is located in north-central Switzerland,[5] at the northwestern tip of Lake Zürich. As of January 2023[update] the municipality had 443,037 inhabitants,[6] the urban area 1.315 million (2009),[7] and the Zürich metropolitan area 1.83 million (2011).[8] Zürich is a hub for railways, roads, and air traffic. Both Zurich Airport and Zürich's main railway station are the largest and busiest in the country.

Permanently settled for over 2,000 years, Zürich was founded by the Romans, who called it Turicum. However, early settlements have been found dating back more than 6,400 years (although this only indicates human presence in the area and not the presence of a town that early).[9] During the Middle Ages, Zürich gained the independent and privileged status of imperial immediacy and, in 1519, became a primary centre of the Protestant Reformation in Europe under the leadership of Huldrych Zwingli.[10]

The official language of Zürich is German,[a] but the main spoken language is Zürich German, the local variant of the Alemannic Swiss German dialect.

Many museums and art galleries can be found in the city, including the Swiss National Museum and Kunsthaus. Schauspielhaus Zürich is generally considered to be one of the most important theatres in the German-speaking world.[11]

As one of Switzerland's primary financial centres, Zürich is home to many financial institutions and banking companies.[12]

Name

In German, the city name is written Zürich and pronounced [ˈtsyːrɪç] . In the local dialect, the name is pronounced without the final consonant and with two short vowels, as Züri [ˈtsyri], although the adjective remains Zürcher(in). The city is called Zurich [zyʁik] in French, Zurigo [dzuˈriːɡo] in Italian, and Turitg [tuˈritɕ] in Romansh.

The name is traditionally written in English as Zurich, without the umlaut. It is pronounced /ˈzjʊərɪk/ ZURE-ik.[13]

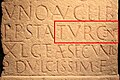

The earliest known form of the city's name is Turicum, attested on a tombstone of the late 2nd century AD in the form STA(tio) TURICEN(sis) ("Turicum customs post"). The name is interpreted as a derivation from a given name, possibly the Gaulish personal name Tūros. The toponym *Turīcon would then mean "belonging to Tūros", "place of Tūros".[14] The Latin stress on the long vowel of the Gaulish name, [tʊˈriːkõː], was lost in German [ˈtsyːrɪç] but is preserved in Italian [dzuˈriːɡo] and in Romansh [tuˈritɕ].

The first development towards its later Germanic form is attested as early as c. 680–700 with the form Ziurichi.[15] From the 9th century onward, the name is established in an Old High German form Zuri(c)h (857 in villa Zurih, 924 in Zurich curtem, 1416 Zürich Stadt).[16]

In Neo-Latin texts dating from c. 1500–1800, Zürich is often referred to as Tigurum; see Tigurini.

-

P(rae)P(ositus) STA(tionis) TVRICEN(sis): "head of Zürich customs post" (detail from a Roman tombstone, c. AD 185–200, discovered in 1747)

-

MON(eta) NOV(a) THVRICENSIS CIVIT(atis) IMPERIALIS: "new coin of Zürich, imperial city", 1512 (with Zürich's patron saints Felix, Regula and Exuperantius)

History

Early history

Settlements of the Neolithic and Bronze Age were found around Lake Zürich. Traces of pre-Roman Celtic, La Tène settlements were discovered near the Lindenhof, a morainic hill dominating the SE - NW waterway constituted by Lake Zurich and the river Limmat.[17] In Roman times, during the conquest of the alpine region in 15 BC, the Romans built a castellum on the Lindenhof.[17] Later here was erected Turicum (a toponym of clear Celtic origin), a tax-collecting point for goods trafficked on the Limmat, which constituted part of the border between Gallia Belgica (from AD 90 Germania Superior) and Raetia: this customs point developed later into a vicus.[17] After Emperor Constantine's reforms in AD 318, the border between Gaul and Italy (two of the four praetorian prefectures of the Roman Empire) was located east of Turicum, crossing the river Linth between Lake Walen and Lake Zürich, where a castle and garrison looked over Turicum's safety. The earliest written record of the town dates from the 2nd century, with a tombstone referring to it as to the Statio Turicensis Quadragesima Galliarum ("Zürich post for collecting the 2.5% value tax of the Galliae"), discovered at the Lindenhof.[17]

In the 5th century, the Germanic Alemanni tribe settled in the Swiss Plateau. The Roman castle remained standing until the 7th century. A Carolingian castle, built on the site of the Roman castle by the grandson of Charlemagne, Louis the German, is mentioned in 835 (in castro Turicino iuxta fluvium Lindemaci). Louis also founded the Fraumünster abbey in 853 for his daughter Hildegard. He endowed the Benedictine convent with the lands of Zürich, Uri, and the Albis forest, and granted the convent immunity, placing it under his direct authority. In 1045, King Henry III granted the convent the right to hold markets, collect tolls, and mint coins, and thus effectively made the abbess the ruler of the city.[18]

Zürich gained Imperial immediacy (Reichsunmittelbar, becoming an Imperial free city) in 1218 with the extinction of the main line of the Zähringer family and attained a status comparable to statehood. During the 1230s, a city wall was built, enclosing 38 hectares, when the earliest stone houses on the Rennweg were built as well. The Carolingian castle was used as a quarry, as it had started to fall into ruin.[19]

Emperor Frederick II promoted the abbess of the Fraumünster to the rank of a duchess in 1234. The abbess nominated the mayor, and she frequently delegated the minting of coins to citizens of the city. The political power of the convent slowly waned in the 14th century, beginning with the establishment of the Zunftordnung (guild laws) in 1336 by Rudolf Brun, who also became the first independent mayor, i.e. not nominated by the abbess.

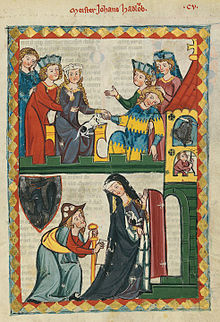

An important event in the early 14th century was the completion of the Manesse Codex, a key source of medieval German poetry. The famous illuminated manuscript – described as "the most beautifully illumined German manuscript in centuries;"[20] – was commissioned by the Manesse family of Zürich, copied and illustrated in the city at some time between 1304 and 1340. Producing such a work was a highly expensive prestige project, requiring several years work by highly skilled scribes[21] and miniature painters, and it clearly testifies to the increasing wealth and pride of Zürich citizens in this period. The work contains 6 songs by Süsskind von Trimberg, who may have been a Jew, since the work itself contains reflections on medieval Jewish life, though little is known about him.[22]

The first mention of Jews in Zürich was in 1273. Sources show that there was a synagogue in Zürich in the 13th century, implying the existence of a Jewish community.[23] With the rise of the Black Death in 1349, Zürich, like most other Swiss cities, responded by persecuting and burning the local Jews, marking the end of the first Jewish community there. The second Jewish community of Zürich, formed towards the end of the 14th century, was short-lived, and Jews were expulsed and banned from the city from 1423 until the 19th century.[24]

Archaeological findings

A woman who died in about 200 BC was found buried in a carved tree trunk during a construction project at the Kern school complex in March 2017 in Aussersihl. Archaeologists revealed that she was approximately 40 years old when she died and likely carried out little physical labor when she was alive. A sheepskin coat, a belt chain, a fancy wool dress, a scarf and a pendant made of glass and amber beads were also discovered with the woman.[25][26][27][28]

Old Swiss Confederacy

On 1 May 1351, the citizens of Zürich had to swear allegiance before representatives of the cantons of Lucerne, Schwyz, Uri and Unterwalden, the other members of the Swiss Confederacy. Thus, Zürich became the fifth member of the Confederacy, which was at that time a loose confederation of de facto independent states. Zürich was the presiding canton of the Diet from 1468 to 1519. This authority was the executive council and lawmaking body of the confederacy, from the Middle Ages until the establishment of the Swiss federal state in 1848. Zürich was temporarily expelled from the confederacy in 1440 due to a war with the other member states over the territory of Toggenburg (the Old Zürich War). Neither side had attained significant victory when peace was agreed upon in 1446, and Zürich was readmitted to the confederation in 1450.[29]

Zwingli started the Swiss Reformation at the time when he was the main preacher at the Grossmünster in 1519. The Zürich Bible was printed by Christoph Froschauer in 1531. The Reformation resulted in major changes in state matters and civil life in Zürich, spreading also to a number of other cantons. Several cantons remained Catholic and became the basis of serious conflicts that eventually led to the outbreak of the Wars of Kappel.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Council of Zürich adopted an isolationist attitude, resulting in a second ring of imposing fortifications built in 1624. The Thirty Years' War which raged across Europe motivated the city to build these walls. The fortifications required a lot of resources, which were taken from subject territories without reaching any agreement. The following revolts were crushed brutally. In 1648, Zürich proclaimed itself a republic, shedding its former status of a free imperial city.[29] In this time the political system of Zürich was an oligarchy (Patriziat): the dominant families of the city were the following ones: Bonstetten, Brun, Bürkli, Escher vom Glas, Escher vom Luchs, Hirzel, Jori (or von Jori), Kilchsperger, Landenberg, Manesse, Meiss, Meyer von Knonau, Mülner, von Orelli.

The Helvetic Revolution of 1798 saw the fall of the Ancien Régime. Zürich lost control of the land and its economic privileges, and the city and the canton separated their possessions between 1803 and 1805. In 1839, the city had to yield to the demands of its urban subjects, following the Züriputsch of 6 September. Most of the ramparts built in the 17th century were torn down, without ever having been besieged, to allay rural concerns over the city's hegemony. The Treaty of Zürich between Austria, France, and Sardinia was signed in 1859.[30][page needed]

Modern history

Zürich was the Federal capital for 1839–40, and consequently, the victory of the Conservative party there in 1839 caused a great stir throughout Switzerland. But when in 1845 the Radicals regained power at Zürich, which was again the Federal capital for 1845–46, Zürich took the lead in opposing the Sonderbund cantons. Following the Sonderbund war and the formation of the Swiss Federal State, Zürich voted in favour of the Federal constitutions of 1848 and of 1874. The enormous immigration from the country districts into the town from the 1830s onwards created an industrial class which, though "settled" in the town, did not possess the privileges of burghership, and consequently had no share in the municipal government. First of all in 1860 the town schools, hitherto open to "settlers" only on paying high fees, were made accessible to all, next in 1875 ten years' residence ipso facto conferred the right of burghership, and in 1893 the eleven outlying districts were incorporated within the town proper.

When Jews began to settle in Zürich following their equality in 1862, the Israelitische Cultusgemeinde Zürich was founded.[31]

Extensive developments took place during the 19th century. From 1847, the Spanisch-Brötli-Bahn, the first railway on Swiss territory, connected Zürich with Baden, putting the Zürich Hauptbahnhof at the origin of the Swiss rail network. The present building of the Hauptbahnhof (the main railway station) dates to 1871. Zürich's Bahnhofstrasse (Station Street) was laid out in 1867, and the Zürich Stock Exchange was founded in 1877. Industrialisation led to migration into the cities and to rapid population growth, particularly in the suburbs of Zürich.

The Quaianlagen are an important milestone in the development of the modern city of Zürich, as the construction of the new lake front transformed Zürich from a small medieval town on the rivers Limmat and Sihl to a modern city on the Zürichsee shore, under the guidance of the city engineer Arnold Bürkli.[32]

In 1893, the twelve outlying districts were incorporated into Zürich, including Aussersihl, the workman's quarter on the left bank of the Sihl, and additional land was reclaimed from Lake Zürich.[33]

In 1934, eight additional districts in the north and west of Zürich were incorporated.

Zürich was accidentally bombed during World War II. As persecuted Jews sought refuge in Switzerland, the SIG (Schweizerischer Israelitischer Gemeindebund, Israelite Community of Switzerland) raised financial resources. The central committee for refugee aid, created in 1933, was located in Zürich.

The canton of Zürich did not recognise the Jewish religious communities as legal entities (and therefore as equal to national churches) until 2005.[31]

Heraldic achievement

a modern version of the heraldic achievement

The coat of arms of Zürich, used by both the city and the canton, consists of a divided field featuring white (argent) and blue (azure). Its origins date back to the 14th century, with the earliest documentation found on a seal of the Imperial Court of Justice from 1384. The shield appeared in colour on a banner in 1437 and on a coin around 1417/18.[34]

When the canton of Zürich was established in 1803, it adopted the heraldic achievement that had been the city's for centuries, and a new version was created for the city by adding a mural crown as a crest. There are slight differences between the supporters of the city and the canton, too: Both have their coats of arms supported by two lions, but the lions of the canton hold a sword and a palm leaf (which had belonged to the city before the canton came into existence; see pictures below).[35]

-

Imperial city (1557)

-

Republic (1723)

-

Capital of the canton of Zürich (1812)

-

The coat of arms on the Town Hall

Politics

City districts

The previous boundaries of the city of Zürich (before 1893) were more or less synonymous with the location of the old town. Two large expansions of the city limits occurred in 1893 and in 1934 when the city of Zürich merged with many surrounding municipalities, that had been growing increasingly together since the 19th century. Today, the city is divided into twelve districts (known as Kreis in German), numbered 1 to 12, each one of which contains between one and four neighborhoods:

- Kreis 1, known as Altstadt, contains the old town, both to the east and west of the start of the Limmat. District 1 contains the neighbourhoods of Hochschulen, Rathaus, Lindenhof, and City.

- Kreis 2 lies along the west side of Lake Zürich, and contains the neighbourhoods of Enge, Wollishofen and Leimbach.

- Kreis 3, known as Wiedikon is between the Sihl and the Uetliberg, and contains the neighbourhoods of Alt-Wiedikon, Sihlfeld and Friesenberg.

- Kreis 4, known as Aussersihl lies between the Sihl and the train tracks leaving Zürich Hauptbahnhof, and contains the neighbourhoods of Werd, Langstrasse, and Hard.

- Kreis 5, known as Industriequartier, is between the Limmat and the train tracks leaving Zürich Hauptbahnhof, it contains the former industrial area of Zürich which has undergone large-scale rezoning to create upscale modern housing, retail, commercial real estate, and a few big vocational schools. It contains the neighborhoods of Gewerbeschule and Escher-Wyss.

- Kreis 6 is on the edge of the Zürichberg, a hill overlooking the eastern part of the city. District 6 contains the neighbourhoods of Oberstrass and Unterstrass.

- Kreis 7 is on the edge of the Adlisberg hill as well as the Zürichberg, on the eastern side of the city. District 7 contains the neighbourhoods of Fluntern, Hottingen, and Hirslanden. These neighbourhoods are home to Zürich's wealthiest and more prominent residents. The Witikon neighbourhood also belongs to district 7.

- Kreis 8, officially called Riesbach, but colloquially known as Seefeld, lies on the eastern side of Lake Zürich. District 8 consists of the neighbourhoods of Seefeld, Mühlebach, and Weinegg.

- Kreis 9 is between the Limmat to the north and the Uetliberg to the south. It contains the neighbourhoods Altstetten and Albisrieden.

- Kreis 10 is to the east of the Limmat and to the south of the Hönggerberg and Käferberg hills. District 10 contains the neighbourhoods of Höngg and Wipkingen.

- Kreis 11 is in the area north of the Hönggerberg and Käferberg and between the Glatt Valley and the Katzensee (Cats Lake). It contains the neighbourhoods of Affoltern, Oerlikon and Seebach.

- Kreis 12, known as Schwamendingen, is located in the Glattal (Glatt valley) on the northern side of the Zürichberg. District 12 contains the neighbourhoods of Saatlen, Schwamendigen Mitte, and Hirzenbach.

Most of the district boundaries are fairly similar to the original boundaries of the previously existing municipalities before they were incorporated into the city of Zürich.

Government

The City Council (Stadtrat) constitutes the executive government of the City of Zürich and operates as a collegiate authority. It is composed of nine councilors, each presiding over a department. Departmental tasks, coordination measures and implementation of laws decreed by the Municipal Council are carried out by the City Council. The regular election of the City Council by any inhabitant valid to vote is held every four years. The mayor (German: Stadtpräsident(in)) is elected as such by a public election by a system of Majorz while the heads of the other departments are assigned by the collegiate. Any resident of Zurich allowed to vote can be elected as a member of the City Council. In the mandate period 2022–2026 (Legislatur) the City Council is presided by mayor Corine Mauch. The executive body holds its meetings in the City Hall (German: Stadthaus), on the left bank of the Limmat. The building was built in 1883 in Renaissance style.

As of May 2023[update], the Zürich City Council is made up of four representatives of the SP (Social Democratic Party, one of whom is the mayor), two members each of the Green Party and the FDP (Free Democratic Party), and one member of GLP (Green Liberal Party), giving the left parties a combined six out of nine seats.[36] The last regular election was held on 13 February 2022.[37]

| City Councilor (Stadtrat / Stadträtin) | Party | Head of Office (Departement, since) | elected since |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corine Mauch[SR 1] | SP | Mayor's Office (Präsidialdepartement, 2009) | 2009 |

| Daniel Leupi | GPS | Finance (Finanzdepartement, 2013) | 2010 |

| Karin Rykart | GPS | Security (Sicherheitsdepartement, 2018) | 2018 |

| Andreas Hauri | GLP | Health and Environment (Gesundheits- und Umweltdepartement, 2018) | 2018 |

| Simone Brander | SP | Civil Engineering and Waste Management (Tiefbau- und Entsorgungsdepartement, 2022) | 2022 |

| André Odermatt | SP | Structural Engineering (Hochbaudepartement, 2010) | 2010 |

| Raphael Golta | SP | Social Services (Sozialdepartement, 2014) | 2014 |

| Michael Baumer | FDP | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Zürich,_Switzerland