A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Varna

Варна | |

|---|---|

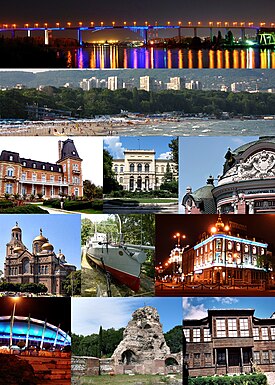

From top left: Asparuh Bridge, Black Sea beach, Euxinograd, Varna Archaeological Museum, Stoyan Bachvarov Dramatic Theatre, Dormition of the Mother of God Cathedral, Drazki torpedo boat, The Navy Club, Palace of Culture and Sports, The ancient Roman baths, Varna Ethnographic Museum | |

| Nickname(s): The marine capital The summer capital | |

| Coordinates: 43°13′N 27°55′E / 43.217°N 27.917°E | |

| Country | Bulgaria |

| Province | Varna |

| Municipality | Varna |

| First settled | 575 BC |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Blagomir Kotsev (PP–DB) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 238 km2 (92 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 80 m (260 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • City | 332,686[1] |

| • Metropolitan | 523,737[1] |

| Demonym | Varnéan |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postcode | 9000 |

| Area code | (+359) 52 |

| Vehicle registration plate | B |

| Website | www |

Varna (Bulgarian: Варна, pronounced [ˈvarnɐ]) is the third-largest city in Bulgaria and the largest city and seaside resort on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast and in the Northern Bulgaria region. Situated strategically in the Gulf of Varna, the city has been a major economic, social and cultural centre for almost three millennia. Historically known as Odessos (Ancient Greek: Ὀδησσός), Varna developed from a Thracian seaside settlement to a major seaport on the Black Sea.

Varna is an important centre for business, transportation, education, tourism, entertainment and healthcare. The city is referred to as the maritime capital of Bulgaria and has the headquarters of the Bulgarian Navy and merchant marine. In 2008, Varna was designated as the seat of the Black Sea Euroregion by the Council of Europe.[2] In 2014, Varna was awarded the title of European Youth Capital 2017.[3]

The oldest gold treasure in the world, belonging to the Varna culture, was discovered in the Varna Necropolis and dated to 4600–4200 BC.[4] Since the discovery of the Varna Necropolis in 1974, 294 burial sites have been found, with over 3000 golden items inside.[5]

Etymology

Theophanes the Confessor first mentions the name Varna, as the city came to be known, within the context of the Slavic conquest of the Balkans in the 6th to 7th centuries. The name could be of Varangian origin, as Varangians had been crossing the Black Sea for many years, reaching Constantinople in the early Middle Ages. In Swedish, värn means 'shield, defense' – hence Varna could mean 'defended, fortified place'. Vikings invaded the settlement during the Middle Ages.[6] The name may be older than that; perhaps it derives from the Proto-Indo-European root *u̯er- 'to flow, wet, water, river'[7][8] (cf. Varuna), or from the Proto-Slavic root varn 'black', or from Iranian bar or var 'camp, fortress' (see also Etymological list of provinces of Bulgaria).

According to Theophanes, in 680 Asparukh, the founder of the First Bulgarian Empire, routed an army of Constantine IV near the Danube River delta. Pursuing those forces, he reached "the so-called Varna near Odyssos [sic] and the midlands thereof" (τὴν λεγομένην Βάρναν, πλησίον Ὀδυσσοῦ). Perhaps the new name applied initially to an adjacent river or lake, a Roman military camp, or an inland area, and only later to the city itself.

By the late 10th century, the name Varna was established so firmly that when Byzantines wrestled back control of the area from the Bulgarians around 975, they kept it rather than restoring the ancient name Odessos.

History

Prehistory

Prehistoric settlements are best known for the Chalcolithic necropolis (mid-5th millennium BC radiocarbon dating), a key archaeological site in world prehistory, eponymous Varna culture and internationally considered the world's oldest large find of gold artefacts, existed within modern city limits. In the wider region of the Varna lakes (before the 1900s, freshwater) and the adjacent karst springs and caves, over 30 prehistoric settlements have been unearthed with the earliest artefacts dating back to the Middle Paleolithic or 100,000 years ago.

Thracians

Since late Bronze Age (13th–12th c. BC) the area around Odessos had been populated with Thracians. During 8th–9th c. BC local Thracians had active commercial and cultural contacts with people from Anatolia, Thessaly, Caucasus and the Mediterranean Sea. These links were reflected in some local productions, for example, forms of bronze fibula of the age, either imported or locally made. There is no doubt that interactions occurred mostly by sea and the bay of Odessos is one of the places where the exchanges took place. Some scholars consider that during the 1st millennium BC, the region was also settled by the half-mythical Cimmerians. An example of their, probably accidental, presence, is the tumulus dated 8th–7th c. BC found near Belogradets, Varna Province.

The region around Odessos was densely populated with Thracians long before the coming of the Greeks on the west seashore of the Black Sea. Pseudo-Scymnus writes: "...Around the city lives the Thracian tribe named Crobises." This is also evidenced by various ceramic pottery, made by hand or by a Potter's wheel, bronze ornaments for horse-fittings and iron weapons, all found in Thracian necropolises dated 6th–4th c. BC near the villages of Dobrina, Kipra, Brestak and other, all in Varna Province. The Thracians in the region were ruled by kings, who entered into unions with the Odrysian kingdom, Getae or Sapaeans—large Thracian states existing between 5th–1st c. BC. Between 336–280 BC these Thracian states along with Odessos were conquered by Alexander the Great.

Archaeological findings have indicated that the population of northeast Thrace was very diverse, including the region around Odessos. During 6th–4th c. BC the region was populated with Scythians who normally inhabited the central Eurasian Steppe (South Russia and Ukraine) and partly the area south of river Istros (the Thracian name of lower Danube). Characteristic for their culture weapons and bronze objects are found all over the region. Scythian horse ornaments are produced in "animal style", which is very close to the Thracian style, a possible explanation for the frequent mixture of both folks in northeastern Thrace. Many bronze artefacts give testimony for such process, for example, applications and front plates for horseheads, as well as moulds for such products in nearby and more distanced settlements. Since the 4th c. BC the region had been populated by more Getae, which is a Thracian tribe populating both shores around the Danube Delta.

Celts started populating the region after their invasion of the Balkan peninsula in 280 BC. All over northeast Bulgaria and even near Odessos were found a significant number of bronze items with Celtic ornaments and typical weapons, all quickly adopted by Thracians. Arkovna, 80 km near Odessos, was probably the permanent capital of Celts' last king Kavar (270/260–216/210 BC). Probably after the downfall of his kingdom, Celts blended with the greatly numbered Thracians in the country. Between the 2nd–1st c. BC in present Dobrudja land between Dyonissopolis (Balchik) and Odessos were created many small Scythian states. Their "kings" minted their coins in mints located in cities on the west Black Sea coast, including Odessos.

The Thracians in northeast Thrace seem to be underdeveloped compared to their counterparts in South Thrace. The people lived in two types of settlements: non-fortified, located in fertile lands near water sources and stone-built fortresses in hard to reach mountain environment, where were usually located the kings' residences. Thracians engaged in farming, wood processing, hunting and fishing. Among their art crafts is metal processing—especially weapons, excelling processing of bronze, making of bracelets, rings, Thracian type of fibulas, horse ornaments, arrowheads. Local goldsmiths used gold and silver to produce typical Thracian plate armour, ceremonial ornaments for the horses of the kings and the aristocracy, as well as valuable pateras and ritons.

Despite ethnic diversity, numerous internal and external conflicts, and cultural differences, the populations of northeastern Bulgaria and the cities along the seashore have demonstrated stable tolerance to each other. Conservatism is easily noticed in ceramic items and in religion. The highest deity of all was the Thracian horseman, who had different names and functions in different places. Water-related deities were honoured as well, such as The Three Graces or the water Nymphs and Zalmoxis by the Getae. During the centuries, especially by the end of the Hellenistic period (2nd–1st c. BC), Thracians adopted the more elaborated Hellenistic culture, thus acting as an intermediate for the continental Thracians.[9]

Antiquity

Odessos or Odessus (Greek: Ὀδησσός)[10][11][12][13][14][15][16] is one of the oldest ancient settlements in Bulgaria. Its name appears as Odesopolis (Ὀδησόπολις) in the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax; and as Odyssos or Odyssus in the Synecdemus and in Procopius.[17] It was established in the second quarter of the sixth century BC (585–550 BC) by Miletian Greeks on the site of a previous Thracian settlement.[18] The Miletian founded an apoikia (trading post) of Odessos towards the end of the 7th c. BC (the earliest Greek archaeological material is dated 600–575 BC), or, according to Pseudo-Scymnus, in the time of Astyages (here, usually 572–570 BC is suggested), within an earlier Thracian settlement. The name Odessos could have been pre-Greek, arguably of Carian origin. It was the presiding member of the Pontic Pentapolis, consisting of Odessos, Tomi, Callatis, Mesembria, and Apollonia.[17] Odessos was a mixed community—contact zone between the Ionian Greeks and the Thracian tribes (Getae, Krobyzoi, Terizi) of the hinterland. Excavations at nearby Thracian sites have shown uninterrupted occupation from the 7th to the 4th century BC and close commercial relations with the colony. The Greek alphabet has been used for inscriptions in Thracian since at least the 5th century BC.

Odessos was included in the assessment of the Delian league of 425 BC. In 339 BC, it was unsuccessfully besieged by Philip II (priests of the Getae persuaded him to conclude a treaty) but surrendered to Alexander the Great in 335 BC, and was later ruled by his diadochus Lysimachus, against whom it rebelled in 313 BC as part of a coalition with other Pontic cities and the Getae. Nevertheless, at the end of the 4th c. BC the city became one of the strongholds of Lysimachus. The city became very prosperous from this time due to strong sea trade with many of the Mediterranean states and cities supported by a wide range of local products. Shortly after 108 BC, Odessos recognised the suzerainty of Mithridates VI of Pontus.

The Roman city, Odessus, first included into the Praefectura orae maritimae and then in 15 AD annexed to the province of Moesia (later Moesia Inferior), covered 47 hectares in present-day central Varna and had prominent public baths, Thermae, erected in the late 2nd century AD (so-called Large (North) Ancient Roman Thermae), now the largest Roman remains in Bulgaria (the building was 100 m (328.08 ft) wide, 70 m (229.66 ft) long, and 25 m (82.02 ft) high) and fourth-largest-known Roman baths in Europe which testify to the importance of the city. There is also the Small (South) Ancient Roman Thermae from the 5th–6th century AD.[19] In addition, archaeologists in 2019 discovered ruins of a building of Roman thermae from the 5th century AD.[20]

Major athletic games were held every five years, possibly attended by Gordian III in 238.

The main aqueduct of Odessos was recently discovered during rescue excavations[21] north of the defensive wall. The aqueduct was built in three construction periods between the 4th and the 6th centuries; in the 4th century the aqueduct was built together with the city wall, then at the end of the 4th to early 5th centuries when a pipeline was laid inside the initial masonry aqueduct. Thirdly in the 6th century, an extra pipeline was added parallel to the original west of it and entered the city through a reconstruction of the fortress wall. The city minted coins, both as an autonomous polis and under the Roman Empire from Trajan to Salonina, the wife of Gallienus, some of which survive.[17]

Odessos was an early Christian centre, as testified by ruins of twelve early basilicas,[22] a monophysite monastery, and indications that one of the Seventy Disciples, Ampliatus, follower of Saint Andrew (who, according to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church legend, preached in the city in 56 CE), served as bishop there. In 6th-century imperial documents, it was referred to as "holiest city," sacratissima civitas. In 442 a peace treaty between Theodosius II and Attila was conducted at Odessos. In 513, it became a focal point of the Vitalian revolt. In 536, Justinian I made it the seat of the Quaestura exercitus ruled by a prefect of Scythia or quaestor Justinianus and including Lower Moesia, Scythia, Caria, the Aegean Islands and Cyprus; later, the military camp outside Odessos was the seat of another senior Roman commander, magister militum per Thracias.

Bulgarian conquest

It has been suggested that the 681 AD peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire that established the new Bulgarian state was concluded at Varna and the first Bulgarian capital south of the Danube may have been provisionally located in its vicinity—possibly in an ancient city near Lake Varna's north shore named Theodorias (Θεοδωριάς) by Justinian I—before it moved to Pliska 70 kilometres (43 miles) to the west.[23] Asparukh fortified the Varna river lowland by a rampart against a possible Byzantine landing; the Asparuhov val (Asparukh's Wall) is still standing. Numerous 7th-century Bulgar settlements have been excavated across the city and further west; the Varna lakes north shores, of all regions, were arguably most densely populated by Bulgars. It has been suggested that Asparukh was aware of the importance of the Roman military camp (campus tribunalis) established by Justinian I outside Odessos and considered it (or its remnants) as the legitimate seat of power for both Lower Moesia and Scythia.

Middle Ages

Control changed from Byzantine to Bulgarian hands several times during the Middle Ages. In the late 9th and the first half of the 10th century, Varna was the site of a principal scriptorium of the Preslav Literary School at a monastery endowed by Boris I who may have also used it as his monastic retreat. The scriptorium may have played a key role in the development of Cyrillic script by Bulgarian scholars under the guidance of one of Saints Cyril and Methodius' disciples. Karel Škorpil suggested that Boris I may have been interred there. The synthetic culture with Hellenistic Thracian, Roman, as well as eastern—Armenian, Syrian, Persian—traits that developed around Odessos in the 6th century under Justinian I, may have influenced the Pliska-Preslav culture of the First Bulgarian Empire, ostensibly in architecture and plastic decorative arts, but possibly also in literature, including Cyrillic scholarship. In 1201, Kaloyan took over the Varna fortress, then in Byzantine hands, on Holy Saturday using a siege tower, and secured it for the Second Bulgarian Empire.

By the late 13th century, with the Treaty of Nymphaeum of 1261, the offensive-defensive alliance between Michael VIII Palaeologus and Genoa that opened up the Black Sea to Genoese commerce, Varna had turned into a thriving commercial port city frequented by Genoese and later also by Venetian and Ragusan merchant ships. The first two maritime republics held consulates and had expatriate colonies there (Ragusan merchants remained active at the port through the 17th century operating from their colony in nearby Provadiya). The city was flanked by two fortresses with smaller commercial ports of their own, Kastritsi and Galata, within sight of each other, and was protected by two other strongholds overlooking the lakes, Maglizh and Petrich. Wheat, animal skins, honey and wax, wine, timber and other local agricultural produce for the Italian and Constantinople markets were the chief exports, and Mediterranean foods and luxury items were imported. The city introduced its own monetary standard, the Varna perper, by the mid-14th century; Bulgarian and Venetian currency exchange rate was fixed by a treaty. Fine jewellery, household ceramics, fine leather and food processing, and other crafts flourished; shipbuilding developed in the Kamchiya river mouth.

Fourteenth-century Italian portolan charts showed Varna as arguably the most important seaport between Constantinople and the Danube delta; they usually labelled the region Zagora. The city was unsuccessfully besieged by Amadeus VI of Savoy, who had captured all Bulgarian fortresses to the south of it, including Galata, in 1366. In 1386, Varna briefly became the capital of the spinoff Principality of Karvuna, then was taken over by the Ottomans in 1389 (and again in 1444), ceded temporarily to Manuel II Palaeologus in 1413 (perhaps until 1444), and sacked by Tatars in 1414.

Battle of Varna

On 10 November 1444, one of the last major battles of the Crusades in European history was fought outside the city walls. Ottomans routed an army of 20,000–30,000 crusaders[24] led by Ladislaus III of Poland (also Ulászló I of Hungary), which had assembled at the port to set sail to Constantinople. The Christian army was attacked by a superior force of 55,000 or 60,000 Ottomans led by sultan Murad II. Ladislaus III was killed in a bold attempt to capture the sultan, earning the sobriquet Warneńczyk (of Varna in Polish; he is also known as Várnai Ulászló in Hungarian or Ladislaus Varnensis in Latin). The failure of the Crusade of Varna made the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 all but inevitable, and Varna (with all of Bulgaria) was to remain under Ottoman domination for over four centuries. Today, there is a cenotaph of Ladislaus III in Varna.

Late Ottoman rule

A major port, agricultural, trade and shipbuilding centre for the Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries, preserving a significant and economically active Bulgarian population, Varna was later made one of the Quadrilateral Fortresses (along with Rousse, Shumen, and Silistra) severing Dobruja from the rest of Bulgaria and containing Russia in the Russo-Turkish wars. The Russians temporarily took over the city in 1773 and again in 1828, following the prolonged Siege of Varna, returning it to the Ottomans two years later after the medieval fortress was razed.

In the early 19th century, many local Greeks joined the patriotic organisation Filiki Eteria. Αt the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence (1821) revolutionary activity was recorded in Varna. As a result, local notables that participated in the Greek national movement were executed by the Ottoman authorities, while others managed to escape to Greece and continue their struggle.[25]

The British and French campaigning against Russia in the Crimean War (1854–1856) used Varna as headquarters and principal naval base; many soldiers died of cholera and the city was devastated by a fire. A British and a French monument mark the cemeteries where cholera victims were interred. In 1866, the first railroad in Bulgaria connected Varna with the Rousse on the Danube, linking the Ottoman capital Constantinople with Central Europe; for a few years, the Orient Express ran through that route. The port of Varna developed as a major supplier of food—notably wheat from the adjacent breadbasket Southern Dobruja—to Constantinople and a busy hub for European imports to the capital; 12 foreign consulates opened in the city. Local Bulgarians took part in the National Revival; Vasil Levski set up a secret revolutionary committee.

Third Bulgarian State

In 1878, the city, which had 26,000 inhabitants, was given to Bulgaria by Russian troops, who entered on 27 July. Varna became a front city in the First Balkan War and the First World War; its economy was badly affected by the temporary loss of its agrarian hinterland of Southern Dobruja to Romania (1913–16 and 1919–40). In the Second World War, the Red Army occupied the city in September 1944 and helped to cement communist rule in Bulgaria.

One of the early centres of industrial development and the Bulgarian labour movement, Varna established itself as the nation's principal port of export, a major grain-producing and viticulture centre, seat of the nation's oldest institution of higher learning outside Sofia, a popular venue for international festivals and events, and the country's de facto summer capital with the erection of the Euxinograd royal summer palace (currently, the Bulgarian government convenes summer sessions there). Mass tourism emerged since the late 1950s. Heavy industry and trade with the Soviet Union boomed in the 1950s to the 1970s.

From 20 December 1949 to 20 October 1956 the city was renamed Stalin by the communist government after Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.[26]

In 1962, the 15th Chess Olympiad, also known as the World Team Championship, organized by FIDE, was held in Varna. In 1969 and 1987, Varna was the host of the World Rhythmic Gymnastics Championships. From 30 September to 4 October 1973, the 10th Olympic Congress took place in the Palace of Culture and Sports.

Varna became a popular resort for Eastern Europeans, who were barred from travelling to the West until 1989. One of them, the veteran East German communist Otto Braun, died on a vacation in Varna in 1974.

Geography

The city occupies 238 km2 (92 sq mi)[27] on verdant terraces (Varna monocline of the Moesian platform) descending from the calcareous Franga Plateau (height 356 m or 1,168 ft) on the north and Avren Plateau on the south, along the horseshoe-shaped Varna Bay of the Black Sea, the elongated Lake Varna, and two artificial waterways connecting the bay and the lake and bridged by the Asparuhov most. It is the centre of a growing conurbation stretching along the seaboard 20 km (12 mi) north and 10 km (6 mi) south (mostly residential and recreational sprawl) and along the lake 25 km (16 mi) west (mostly transportation and industrial facilities). Since antiquity, the city has been surrounded by vineyards, orchards, and forests. Commercial shipping facilities are being relocated inland into the lakes and canals, while the bay remains a recreation area; almost all the waterfront is parkland.

The urban area has in excess of 20 km of sand beaches and abounds in thermal mineral water sources (temperature 35–55 °C or 95–131 °F). It enjoys a mild climate influenced by the sea with long, mild, akin to Mediterranean, autumns, and sunny and hot, yet considerably cooler than Mediterranean summers moderated by breezes and regular rainfall. Although Varna receives about two-thirds of the average rainfall for Bulgaria, abundant groundwater keeps its wooded hills lush throughout summer. The city is cut off from north and northeast winds by hills along the north arm of the bay, yet January and February still can be bitterly cold at times, with blizzards. Black Sea water has become cleaner after 1989 due to decreased chemical fertiliser in farming; it has low salinity, lacks large predators or poisonous species, and the tidal range is virtually imperceptible.

The city lies 470 km (292 mi) north-east of Sofia; the nearest major cities are Dobrich (45 km or 28 mi to the north), Shumen (80 km or 50 mi to the west), and Burgas (125 km or 78 mi to the south-west).

Climate

Varna has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa). The specific Black sea climate is milder than the inland parts of the country and the sea influence lowers the effect of the occasional cold air masses from the north-east. Average precipitation is the lowest for the country and sunshine is abundant.[28] The summer begins in early May and lasts till early October. Temperatures in summer usually vary 27–30 °C (81–86 °F) during the day and between 17–18 °C (63–64 °F) at the night. Seawater temperature during the summer months is usually at the range 24–27 °C (75–81 °F).[29] In winter temperatures are about 6–7 °C (43–45 °F) during the day and 0 °C (32 °F) at night. Snow is possible in the coldest months, but can quickly melt. The highest temperature ever recorded was 41.4 °C (106.5 °F) in July 1927 and the lowest −24.3 °C (−11.7 °F) in February 1929.

| Climate data for Varna (normals for 1991–2020 extremes 1961–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.2 (70.2) |

22.6 (72.7) |

29.5 (85.1) |

30.7 (87.3) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36.8 (98.2) |

40.0 (104.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

32.1 (89.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

26.1 (79.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29.4 (84.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

17.7 (63.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

19.1 (66.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

4.3 (39.7) |

12.8 (55.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −0.5 (31.1) |

0.3 (32.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.5 (50.9) |

5.9 (42.6) |

1.3 (34.3) |

9.2 (48.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.8 (0.0) |

−16.0 (3.2) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

2.5 (36.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.2 (50.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 45 (1.8) |

33 (1.3) |

32 (1.3) |

38 (1.5) |

38 (1.5) |

52 (2.0) |

48 (1.9) |

29 (1.1) |

49 (1.9) |

56 (2.2) |

49 (1.9) |

47 (1.9) |

516 (20.3) Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Varna,_Bulgaria Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk |