A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Supreme Court of the United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| 38°53′26″N 77°00′16″W / 38.89056°N 77.00444°W | |

| Established | March 4, 1789[1] |

| Location | 1 First Street, NE, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′26″N 77°00′16″W / 38.89056°N 77.00444°W |

| Composition method | Presidential nomination with Senate confirmation |

| Authorized by | U.S. Constitution |

| Judge term length | Life tenure |

| Number of positions | 9, by statute |

| Website | supremecourt |

| Chief Justice of the United States | |

| Currently | John Roberts |

| Since | September 29, 2005 |

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on questions of U.S. constitutional or federal law. It also has original jurisdiction over a narrow range of cases, specifically "all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party."[2] The court holds the power of judicial review: the ability to invalidate a statute for violating a provision of the Constitution. It is also able to strike down presidential directives for violating either the Constitution or statutory law.[3]

Established by Article Three of the United States Constitution, the composition and procedures of the Supreme Court were originally established by the 1st Congress through the Judiciary Act of 1789. The court consists of nine justices: the chief justice of the United States and eight associate justices, and the justices meet at the Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C. Justices have lifetime tenure, meaning they remain on the court until they die, retire, resign, or are impeached and removed from office.[3] When a vacancy occurs, the president, with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoints a new justice. Each justice has a single vote in deciding the cases argued before the court. When in the majority, the chief justice decides who writes the opinion of the court; otherwise, the most senior justice in the majority assigns the task of writing the opinion.

The Supreme Court receives on average about 7,000 petitions for writs of certiorari each year, but grants only about 80.[4]

History

It was while debating the separation of powers between the legislative and executive departments that delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention established the parameters for the national judiciary. Creating a "third branch" of government was a novel idea[citation needed]; in the English tradition, judicial matters had been treated as an aspect of royal (executive) authority. Early on, the delegates who were opposed to having a strong central government argued that national laws could be enforced by state courts, while others, including James Madison, advocated for a national judicial authority consisting of tribunals chosen by the national legislature. It was proposed that the judiciary should have a role in checking the executive's power to veto or revise laws.[citation needed]

Eventually, the framers compromised by sketching only a general outline of the judiciary in Article Three of the United States Constitution, vesting federal judicial power in "one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish."[5][6][better source needed] They delineated neither the exact powers and prerogatives of the Supreme Court nor the organization of the judicial branch as a whole.[citation needed]

The 1st United States Congress provided the detailed organization of a federal judiciary through the Judiciary Act of 1789. The Supreme Court, the country's highest judicial tribunal, was to sit in the nation's capital and would initially be composed of a chief justice and five associate justices. The act also divided the country into judicial districts, which were in turn organized into circuits. Justices were required to "ride circuit" and hold circuit court twice a year in their assigned judicial district.[7][non-primary source needed]

Immediately after signing the act into law, President George Washington nominated the following people to serve on the court: John Jay for chief justice and John Rutledge, William Cushing, Robert H. Harrison, James Wilson, and John Blair Jr. as associate justices. All six were confirmed by the Senate on September 26, 1789; however, Harrison declined to serve, and Washington later nominated James Iredell in his place.[8][non-primary source needed]

The Supreme Court held its inaugural session from February 2 through February 10, 1790, at the Royal Exchange in New York City, then the U.S. capital.[9] A second session was held there in August 1790.[10] The earliest sessions of the court were devoted to organizational proceedings, as the first cases did not reach it until 1791.[7] When the nation's capital was moved to Philadelphia in 1790, the Supreme Court did so as well. After initially meeting at Independence Hall, the court established its chambers at City Hall.[11]

Early beginnings

Under chief justices Jay, Rutledge, and Ellsworth (1789–1801), the court heard few cases; its first decision was West v. Barnes (1791), a case involving procedure.[12] As the court initially had only six members, every decision that it made by a majority was also made by two-thirds (voting four to two).[13] However, Congress has always allowed less than the court's full membership to make decisions, starting with a quorum of four justices in 1789.[14] The court lacked a home of its own and had little prestige,[15] a situation not helped by the era's highest-profile case, Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), which was reversed within two years by the adoption of the Eleventh Amendment.[16]

The court's power and prestige grew substantially during the Marshall Court (1801–1835).[17] Under Marshall, the court established the power of judicial review over acts of Congress,[18] including specifying itself as the supreme expositor of the Constitution (Marbury v. Madison)[19][20] and making several important constitutional rulings that gave shape and substance to the balance of power between the federal government and states, notably Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, McCulloch v. Maryland, and Gibbons v. Ogden.[21][22][23][24]

The Marshall Court also ended the practice of each justice issuing his opinion seriatim,[25] a remnant of British tradition,[26] and instead issuing a single majority opinion.[25] Also during Marshall's tenure, although beyond the court's control, the impeachment and acquittal of Justice Samuel Chase from 1804 to 1805 helped cement the principle of judicial independence.[27][28]

From Taney to Taft

The Taney Court (1836–1864) made several important rulings, such as Sheldon v. Sill, which held that while Congress may not limit the subjects the Supreme Court may hear, it may limit the jurisdiction of the lower federal courts to prevent them from hearing cases dealing with certain subjects.[29] Nevertheless, it is primarily remembered for its ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford,[30] which helped precipitate the American Civil War.[31] In the Reconstruction era, the Chase, Waite, and Fuller Courts (1864–1910) interpreted the new Civil War amendments to the Constitution[24] and developed the doctrine of substantive due process (Lochner v. New York;[32] Adair v. United States).[33] The size of the court was last changed in 1869, when it was set at nine.

Under the White and Taft Courts (1910–1930), the court held that the Fourteenth Amendment had incorporated some guarantees of the Bill of Rights against the states (Gitlow v. New York),[34] grappled with the new antitrust statutes (Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States), upheld the constitutionality of military conscription (Selective Draft Law Cases),[35] and brought the substantive due process doctrine to its first apogee (Adkins v. Children's Hospital).[36]

New Deal era

During the Hughes, Stone, and Vinson courts (1930–1953), the court gained its own accommodation in 1935[37] and changed its interpretation of the Constitution, giving a broader reading to the powers of the federal government to facilitate President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal (most prominently West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, Wickard v. Filburn, United States v. Darby, and United States v. Butler).[38][39][40] During World War II, the court continued to favor government power, upholding the internment of Japanese Americans (Korematsu v. United States) and the mandatory Pledge of Allegiance (Minersville School District v. Gobitis). Nevertheless, Gobitis was soon repudiated (West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette), and the Steel Seizure Case restricted the pro-government trend.

The Warren Court (1953–1969) dramatically expanded the force of Constitutional civil liberties.[41] It held that segregation in public schools violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (Brown v. Board of Education, Bolling v. Sharpe, and Green v. County School Bd.)[42] and that legislative districts must be roughly equal in population (Reynolds v. Sims). It recognized a general right to privacy (Griswold v. Connecticut),[43] limited the role of religion in public school, most prominently Engel v. Vitale and Abington School District v. Schempp,[44][45] incorporated most guarantees of the Bill of Rights against the states, prominently Mapp v. Ohio (the exclusionary rule) and Gideon v. Wainwright (right to appointed counsel),[46][47] and required that criminal suspects be apprised of all these rights by police (Miranda v. Arizona).[48] At the same time, the court limited defamation suits by public figures (New York Times Co. v. Sullivan) and supplied the government with an unbroken run of antitrust victories.[49]

Burger, Rehnquist, and Roberts

The Burger Court (1969–1986) saw a conservative shift.[50] It also expanded Griswold's right to privacy to strike down abortion laws (Roe v. Wade)[51] but divided deeply on affirmative action (Regents of the University of California v. Bakke)[52] and campaign finance regulation (Buckley v. Valeo).[53] It also wavered on the death penalty, ruling first that most applications were defective (Furman v. Georgia),[54] but later that the death penalty itself was not unconstitutional (Gregg v. Georgia).[54][55][56]

The Rehnquist Court (1986–2005) was known for its revival of judicial enforcement of federalism,[57] emphasizing the limits of the Constitution's affirmative grants of power (United States v. Lopez) and the force of its restrictions on those powers (Seminole Tribe v. Florida, City of Boerne v. Flores).[58][59][60][61][62] It struck down single-sex state schools as a violation of equal protection (United States v. Virginia), laws against sodomy as violations of substantive due process (Lawrence v. Texas)[63] and the line-item veto (Clinton v. New York) but upheld school vouchers (Zelman v. Simmons-Harris) and reaffirmed Roe's restrictions on abortion laws (Planned Parenthood v. Casey).[64] The court's decision in Bush v. Gore, which ended the electoral recount during the 2000 United States presidential election, remains especially controversial with debate ongoing over the rightful winner and whether or not the ruling should set a precedent.[65][66][67][68]

The Roberts Court (2005–present) is regarded as more conservative and controversial than the Rehnquist Court.[69][70][71][72] Some of its major rulings have concerned federal preemption (Wyeth v. Levine), civil procedure (Twombly–Iqbal), voting rights and federal preclearance (Shelby County–Brnovich), abortion (Gonzales v. Carhart and Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization),[73] climate change (Massachusetts v. EPA), same-sex marriage (United States v. Windsor and Obergefell v. Hodges), and the Bill of Rights, such as in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission and Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta (First Amendment),[74] Heller–McDonald–Bruen (Second Amendment),[75] and Baze v. Rees (Eighth Amendment).[76][77]

Composition

Nomination, confirmation, and appointment

Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, known as the Appointments Clause, empowers the president to nominate and, with the confirmation (advice and consent) of the United States Senate, to appoint public officials, including justices of the Supreme Court. This clause is one example of the system of checks and balances inherent in the Constitution. The president has the plenary power to nominate, while the Senate possesses the plenary power to reject or confirm the nominee. The Constitution sets no qualifications for service as a justice, such as age, citizenship, residence or prior judicial experience, thus a president may nominate anyone to serve, and the Senate may not set any qualifications or otherwise limit who the president can choose.[78][79][80]

In modern times, the confirmation process has attracted considerable attention from the press and advocacy groups, which lobby senators to confirm or to reject a nominee depending on whether their track record aligns with the group's views. The Senate Judiciary Committee conducts hearings and votes on whether the nomination should go to the full Senate with a positive, negative or neutral report. The committee's practice of personally interviewing nominees is relatively recent. The first nominee to appear before the committee was Harlan Fiske Stone in 1925, who sought to quell concerns about his links to Wall Street, and the modern practice of questioning began with John Marshall Harlan II in 1955.[81] Once the committee reports out the nomination, the full Senate considers it. Rejections are relatively uncommon; the Senate has explicitly rejected twelve Supreme Court nominees, most recently Robert Bork, nominated by President Ronald Reagan in 1987.

Although Senate rules do not necessarily allow a negative or tied vote in committee to block a nomination, prior to 2017 a nomination could be blocked by filibuster once debate had begun in the full Senate. President Lyndon B. Johnson's nomination of sitting associate justice Abe Fortas to succeed Earl Warren as Chief Justice in 1968 was the first successful filibuster of a Supreme Court nominee. It included both Republican and Democratic senators concerned with Fortas's ethics. President Donald Trump's nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the seat left vacant by Antonin Scalia's death was the second. Unlike the Fortas filibuster, only Democratic senators voted against cloture on the Gorsuch nomination, citing his perceived conservative judicial philosophy, and the Republican majority's prior refusal to take up President Barack Obama's nomination of Merrick Garland to fill the vacancy.[82] This led the Republican majority to change the rules and eliminate the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations.[83]

Not every Supreme Court nominee has received a floor vote in the Senate. A president may withdraw a nomination before an actual confirmation vote occurs, typically because it is clear that the Senate will reject the nominee; this occurred with President George W. Bush's nomination of Harriet Miers in 2005. The Senate may also fail to act on a nomination, which expires at the end of the session. President Dwight Eisenhower's first nomination of John Marshall Harlan II in November 1954 was not acted on by the Senate; Eisenhower re-nominated Harlan in January 1955, and Harlan was confirmed two months later. Most recently, the Senate failed to act on the March 2016 nomination of Merrick Garland, as the nomination expired in January 2017, and the vacancy was filled by Neil Gorsuch, an appointee of President Trump.[84]

Once the Senate confirms a nomination, the president must prepare and sign a commission, to which the Seal of the Department of Justice must be affixed, before the appointee can take office.[85] The seniority of an associate justice is based on the commissioning date, not the confirmation or swearing-in date.[86] After receiving their commission, the appointee must then take the two prescribed oaths before assuming their official duties.[87] The importance of the oath taking is underscored by the case of Edwin M. Stanton. Although confirmed by the Senate on December 20, 1869, and duly commissioned as an associate justice by President Ulysses S. Grant, Stanton died on December 24, prior to taking the prescribed oaths. He is not, therefore, considered to have been a member of the court.[88][89]

Before 1981, the approval process of justices was usually rapid. From the Truman through Nixon administrations, justices were typically approved within one month. From the Reagan administration to the present, the process has taken much longer and some believe this is because Congress sees justices as playing a more political role than in the past.[90] According to the Congressional Research Service, the average number of days from nomination to final Senate vote since 1975 is 67 days (2.2 months), while the median is 71 days (2.3 months).[91][92]

Recess appointments

When the Senate is in recess, a president may make temporary appointments to fill vacancies. Recess appointees hold office only until the end of the next Senate session (less than two years). The Senate must confirm the nominee for them to continue serving; of the two chief justices and eleven associate justices who have received recess appointments, only Chief Justice John Rutledge was not subsequently confirmed.[93]

No U.S. president since Dwight D. Eisenhower has made a recess appointment to the court, and the practice has become rare and controversial even in lower federal courts.[94] In 1960, after Eisenhower had made three such appointments, the Senate passed a "sense of the Senate" resolution that recess appointments to the court should only be made in "unusual circumstances";[95] such resolutions are not legally binding but are an expression of Congress's views in the hope of guiding executive action.[95][96]

The Supreme Court's 2014 decision in National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning limited the ability of the president to make recess appointments (including appointments to the Supreme Court); the court ruled that the Senate decides when the Senate is in session or in recess. Writing for the court, Justice Breyer stated, "We hold that, for purposes of the Recess Appointments Clause, the Senate is in session when it says it is, provided that, under its own rules, it retains the capacity to transact Senate business."[97] This ruling allows the Senate to prevent recess appointments through the use of pro-forma sessions.[98]

Tenure

Lifetime tenure of justices can only be found for US Supreme Court Justices and the State of Rhode Island's Supreme Court justices, with all other democratic nations and all other US states having set term limits or mandatory retirement ages.[99] Larry Sabato wrote: "The insularity of lifetime tenure, combined with the appointments of relatively young attorneys who give long service on the bench, produces senior judges representing the views of past generations better than views of the current day."[100] Sanford Levinson has been critical of justices who stayed in office despite medical deterioration based on longevity.[101] James MacGregor Burns stated lifelong tenure has "produced a critical time lag, with the Supreme Court institutionally almost always behind the times."[102] Proposals to solve these problems include term limits for justices, as proposed by Levinson[103] and Sabato[100][104] and a mandatory retirement age proposed by Richard Epstein,[105] among others.[106] Alexander Hamilton in Federalist 78 argued that one benefit of lifetime tenure was that, "nothing can contribute so much to its firmness and independence as permanency in office."[107][non-primary source needed]

Article Three, Section 1 of the Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their offices during good behavior", which is understood to mean that they may serve for the remainder of their lives, until death; furthermore, the phrase is generally interpreted to mean that the only way justices can be removed from office is by Congress via the impeachment process. The Framers of the Constitution chose good behavior tenure to limit the power to remove justices and to ensure judicial independence.[108][109][110] No constitutional mechanism exists for removing a justice who is permanently incapacitated by illness or injury, but unable (or unwilling) to resign.[111] The only justice ever to be impeached was Samuel Chase, in 1804. The House of Representatives adopted eight articles of impeachment against him; however, he was acquitted by the Senate, and remained in office until his death in 1811.[112] No subsequent effort to impeach a sitting justice has progressed beyond referral to the Judiciary Committee. (For example, William O. Douglas was the subject of hearings twice, in 1953 and again in 1970; and Abe Fortas resigned while hearings were being organized in 1969.)

Because justices have indefinite tenure, timing of vacancies can be unpredictable. Sometimes they arise in quick succession, as in September 1971, when Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II left within days of each other, the shortest period of time between vacancies in the court's history.[113] Sometimes a great length of time passes between vacancies, such as the 11-year span, from 1994 to 2005, from the retirement of Harry Blackmun to the death of William Rehnquist, which was the second longest timespan between vacancies in the court's history.[114] On average a new justice joins the court about every two years.[115]

Despite the variability, all but four presidents have been able to appoint at least one justice. William Henry Harrison died a month after taking office, although his successor (John Tyler) made an appointment during that presidential term. Likewise, Zachary Taylor died 16 months after taking office, but his successor (Millard Fillmore) also made a Supreme Court nomination before the end of that term. Andrew Johnson, who became president after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, was denied the opportunity to appoint a justice by a reduction in the size of the court. Jimmy Carter is the only person elected president to have left office after at least one full term without having the opportunity to appoint a justice. Presidents James Monroe, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and George W. Bush each served a full term without an opportunity to appoint a justice, but made appointments during their subsequent terms in office. No president who has served more than one full term has gone without at least one opportunity to make an appointment.

Size of the court

One of the smallest Supreme Courts in the world, the US Supreme Court consists of nine members: one chief justice and eight associate justices. The U.S. Constitution does not specify the size of the Supreme Court, nor does it specify any specific positions for the court's members. The Constitution assumes the existence of the office of the chief justice, because it mentions in Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 that "the Chief Justice" must preside over impeachment trials of the President of the United States. The power to define the Supreme Court's size and membership has been assumed to belong to Congress, which initially established a six-member Supreme Court composed of a chief justice and five associate justices through the Judiciary Act of 1789.

The size of the court was first altered by the Midnight Judges Act of 1801 which would have reduced the size of the court to five members upon its next vacancy (as federal judges have life tenure), but the Judiciary Act of 1802 promptly negated the 1801 act, restoring the court's size to six members before any such vacancy occurred. As the nation's boundaries grew across the continent and as Supreme Court justices in those days had to ride the circuit, an arduous process requiring long travel on horseback or carriage over harsh terrain that resulted in months-long extended stays away from home, Congress added justices to correspond with the growth such that the number of seats for associate justices plus the chief justice became seven in 1807, nine in 1837, and ten in 1863.[116][117]

At the behest of Chief Justice Chase, and in an attempt by the Republican Congress to limit the power of Democrat Andrew Johnson, Congress passed the Judicial Circuits Act of 1866, providing that the next three justices to retire would not be replaced, which would thin the bench to seven justices by attrition. Consequently, one seat was removed in 1866 and a second in 1867. Soon after Johnson left office, the new president Ulysses S. Grant,[118] a Republican, signed into law the Judiciary Act of 1869. This returned the number of justices to nine[119] (where it has since remained), and allowed Grant to immediately appoint two more judges.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted to expand the court in 1937. His proposal envisioned the appointment of one additional justice for each incumbent justice who reached the age of 70 years 6 months and refused retirement, up to a maximum bench of 15 justices. The proposal was ostensibly to ease the burden of the docket on elderly judges, but the actual purpose was widely understood as an effort to "pack" the court with justices who would support Roosevelt's New Deal.[120] The plan, usually called the "court-packing plan", failed in Congress after members of Roosevelt's own Democratic Party believed it to be unconstitutional. It was defeated 70–20 in the Senate, and the Senate Judiciary Committee reported that it was "essential to the continuance of our constitutional democracy" that the proposal "be so emphatically rejected that its parallel will never again be presented to the free representatives of the free people of America."[121][122][123][124]

The expansion of the 5–4 conservative majority on the court to a 6–3 supermajority[125] during the presidency of Donald Trump led Joan Biskupic of CNN to consider the court the most conservative since the 1930s, with Republicans appointing 14 of the last 18 justices.[126] Some Democrats have called for an expansion in the court's size to fix what they see as an imbalance. In April 2021, during the 117th Congress, some Democrats in the House of Representatives introduced the Judiciary Act of 2021, a bill to expand the Supreme Court from nine to 13 seats. It met opposition within the party, and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi refused to bring it to the floor.[127][128] Shortly after taking office in January 2021, Joe Biden established a presidential commission to study possible reforms to the Supreme Court. The commission's December 2021 final report discussed but took no position on expanding the size of the court.[129]

At nine members, the U.S. Supreme Court is one of the smallest supreme courts in the world. David Litt argues the court is too small to represent the perspectives of a country the United States' size.[130] Lawyer and legal scholar Jonathan Turley advocates for 19 justices, with the court being gradually expanded by two new members per presidential term, bringing the U.S. Supreme Court to a similar size as its counterparts in other developed countries. He says that a bigger court would reduce the power of the swing justice, ensure the court has "a greater diversity of views", and make confirmation of new justices less politically contentious.[131][132]

Membership

Current justices

There are currently nine justices on the Supreme Court: Chief Justice John Roberts and eight associate justices. Among the current members of the court, Clarence Thomas is the longest-serving justice, with a tenure of 11,875 days (32 years, 187 days) as of April 27, 2024; the most recent justice to join the court is Ketanji Brown Jackson, whose tenure began on June 30, 2022, after being confirmed by the senate on April 7.[133]

| Justice / birthdate and place |

Appointed by (party) | SCV | Age at | Start date / length of service |

Succeeded | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | Present | ||||||

|

(Chief Justice) John Roberts January 27, 1955 Buffalo, New York |

G. W. Bush (R) |

78–22 | 50 | 69 | September 29, 2005 18 years, 211 days |

Rehnquist |

|

Clarence Thomas June 23, 1948 Pin Point, Georgia |

G. H. W. Bush (R) |

52–48 | 43 | 75 | October 23, 1991 32 years, 187 days |

Marshall |

|

Samuel Alito April 1, 1950 Trenton, New Jersey |

G. W. Bush (R) |

58–42 | 55 | 74 | January 31, 2006 18 years, 87 days |

O'Connor |

|

Sonia Sotomayor June 25, 1954 New York City, New York |

Obama (D) |

68–31 | 55 | 69 | August 8, 2009 14 years, 263 days |

Souter |

|

Elena Kagan April 28, 1960 New York City, New York |

Obama (D) |

63–37 | 50 | 63 | August 7, 2010 13 years, 264 days |

Stevens |

|

Neil Gorsuch August 29, 1967 Denver, Colorado |

Trump (R) |

54–45 | 49 | 56 | April 10, 2017 7 years, 17 days |

Scalia |

|

Brett Kavanaugh February 12, 1965 Washington, D.C. |

Trump (R) |

50–48 | 53 | 59 | October 6, 2018 5 years, 204 days |

Kennedy |

|

Amy Coney Barrett January 28, 1972 New Orleans, Louisiana |

Trump (R) |

52–48 | 48 | 52 | October 27, 2020 3 years, 183 days |

Ginsburg |

|

Ketanji Brown Jackson September 14, 1970 Washington, D.C. |

Biden (D) |

53–47 | 51 | 53 | June 30, 2022 1 year, 302 days |

Breyer |

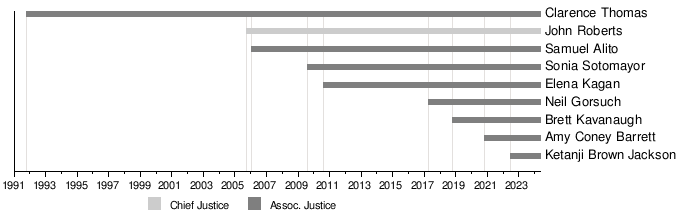

This graphical timeline depicts the length of each current Supreme Court justice's tenure (not seniority, as the chief justice has seniority over all associate justices regardless of tenure) on the court:

Court demographics

The court currently has five male and four female justices. Among the nine justices, there are two African American justices (Justices Thomas and Jackson) and one Hispanic justice (Justice Sotomayor). One of the justices was born to at least one immigrant parent: Justice Alito's father was born in Italy.[135][136]

At least six justices are Roman Catholics, one is Jewish, and one is Protestant. It is unclear whether Neil Gorsuch considers himself a Catholic or an Episcopalian.[137] Historically, most justices have been Protestants, including 36 Episcopalians, 19 Presbyterians, 10 Unitarians, 5 Methodists, and 3 Baptists.[138][139] The first Catholic justice was Roger Taney in 1836,[140] and 1916 saw the appointment of the first Jewish justice, Louis Brandeis.[141] In recent years the historical situation has reversed, as most recent justices have been either Catholic or Jewish.

Three justices are from the state of New York, two are from Washington, D.C., and one each is from New Jersey, Georgia, Colorado, and Louisiana.[142][143][144] Eight of the current justices received their Juris Doctor from an Ivy League law school: Neil Gorsuch, Ketanji Brown Jackson, Elena Kagan and John Roberts from Harvard; plus Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, Sonia Sotomayor and Clarence Thomas from Yale. Only Amy Coney Barrett did not; she received her Juris Doctor at Notre Dame.

Previous positions or offices, judicial or federal government, prior to joining the court (by order of seniority following the Chief Justice) include: