A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

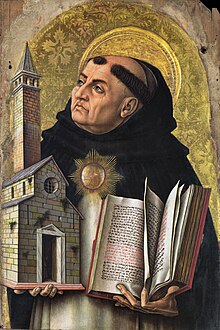

Thomas Aquinas OP (/əˈkwaɪnəs/, ə-KWY-nəs; Italian: Tommaso d'Aquino, lit. 'Thomas of Aquino'; c. 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian[6] Dominican friar and priest, an influential philosopher and theologian, and a jurist in the tradition of scholasticism from the county of Aquino in the Kingdom of Sicily.

Thomas was a proponent of natural theology and the father of a school of thought (encompassing both theology and philosophy) known as Thomism. He argued that God is the source of the light of natural reason and the light of faith.[7] He embraced[8] several ideas put forward by Aristotle and attempted to synthesize Aristotelian philosophy with the principles of Christianity.[9] He has been described as "the most influential thinker of the medieval period"[10] and "the greatest of the medieval philosopher-theologians".[11] According to the English philosopher Anthony Kenny, Thomas was "one of the greatest philosophers of the Western world".[12]

Thomas's best-known works are the unfinished Summa Theologica, or Summa Theologiae (1265–1274), the Disputed Questions on Truth (1256–1259) and the Summa contra Gentiles (1259–1265). His commentaries on Christian Scripture and on Aristotle also form an important part of his body of work. He is also notable for his Eucharistic hymns, which form a part of the Church's liturgy.[13]

As a Doctor of the Church, Thomas Aquinas is considered one of the Catholic Church's greatest theologians and philosophers.[14] He is known in Catholic theology as the Doctor Angelicus ("Angelic Doctor", with the title "doctor" meaning "teacher"), and the Doctor Communis ("Universal Doctor").[a] In 1999, John Paul II added a new title to these traditional ones: Doctor Humanitatis ("Doctor of Humanity/Humaneness").[15]

Biography

Early life (1225–1244)

Thomas Aquinas was most likely born in the family castle of Roccasecca,[16] near Aquino, controlled at that time by the Kingdom of Sicily (in present-day Lazio, Italy), c. 1225.[17] He was born to the most powerful branch of the family, and his father, Landulf of Aquino, was a man of means. As a knight in the service of Emperor Frederick II, Landulf of Aquino held the title miles.[18] Thomas's mother, Theodora, belonged to the Rossi branch of the Neapolitan Caracciolo family.[19] Landulf's brother Sinibald was abbot of Monte Cassino, the oldest Benedictine monastery. While the rest of the family's sons pursued military careers,[20] the family intended for Thomas to follow his uncle into the abbacy;[21] this would have been a normal career path for a younger son of Southern Italian nobility.[22]

At the age of five Thomas began his early education at Monte Cassino, but after the military conflict between Emperor Frederick II and Pope Gregory IX spilt into the abbey in early 1239, Landulf and Theodora had Thomas enrolled at the studium generale (university) established by Frederick in Naples.[23] There, his teacher in arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music was Petrus de Ibernia.[24] It was at this university that Thomas was presumably introduced to Aristotle, Averroes and Maimonides, all of whom would influence his theological philosophy.[25] During his study at Naples, Thomas also came under the influence of John of St. Julian, a Dominican preacher in Naples, who was part of the active effort by the Dominican Order to recruit devout followers.[26]

At the age of nineteen, Thomas resolved to join the Dominican Order. His change of heart, however, did not please his family.[27] In an attempt to prevent Theodora's interference in Thomas's choice, the Dominicans arranged to move Thomas to Rome, and from Rome, to Paris.[28] However, while on his journey to Rome, per Theodora's instructions, his brothers seized him as he was drinking from a spring and took him back to his parents at the castle of Monte San Giovanni Campano.[28]

Thomas was held prisoner for almost one year in the family castles at Monte San Giovanni and Roccasecca in an attempt to prevent him from assuming the Dominican habit and to push him into renouncing his new aspiration.[25] Political concerns prevented the Pope from ordering Thomas's release, which had the effect of extending Thomas's detention.[29] Thomas passed this time of trial tutoring his sisters and communicating with members of the Dominican Order.[25]

Family members became desperate to dissuade Thomas, who remained determined to join the Dominicans. At one point, two of his brothers resorted to the measure of hiring a prostitute to seduce him, presumably because sexual temptation might dissuade him from a life of celibacy. According to the official records for his canonization, Thomas drove her away wielding a burning log—with which he inscribed a cross onto the wall—and fell into a mystical ecstasy; two angels appeared to him as he slept and said, "Behold, we gird thee by the command of God with the girdle of chastity, which henceforth will never be imperilled. What human strength can not obtain, is now bestowed upon thee as a celestial gift." From then onwards, Thomas was given the grace of perfect chastity by Christ, a girdle he wore till the end of his life. The girdle was given to the ancient monastery of Vercelli in Piedmont, and is now at Chieri, near Turin.[30][31]

By 1244, seeing that all her attempts to dissuade Thomas had failed, Theodora sought to save the family's dignity, arranging for Thomas to escape at night through his window. In her mind, a secret escape from detention was less damaging than an open surrender to the Dominicans. Thomas was sent first to Naples and then to Rome to meet Johannes von Wildeshausen, the Master General of the Dominican Order.[32]

Paris, Cologne, Albert Magnus, and first Paris regency (1245–1259)

In 1245, Thomas was sent to study at the Faculty of the Arts at the University of Paris, where he most likely met Dominican scholar Albertus Magnus,[33] then the holder of the Chair of Theology at the College of St. James in Paris.[34] When Albertus was sent by his superiors to teach at the new studium generale at Cologne in 1248,[33] Thomas followed him, declining Pope Innocent IV's offer to appoint him abbot of Monte Cassino as a Dominican.[21] Albertus then appointed the reluctant Thomas magister studentium.[22] Because Thomas was quiet and did not speak much, some of his fellow students thought he was slow. But Albertus prophetically exclaimed: "You call him the dumb ox , but in his teaching he will one day produce such a bellowing that it will be heard throughout the world".[21]

Thomas taught in Cologne as an apprentice professor (baccalaureus biblicus), instructing students on the books of the Old Testament and writing Expositio super Isaiam ad litteram (Literal Commentary on Isaiah), Postilla super Ieremiam (Commentary on Jeremiah), and Postilla super Threnos (Commentary on Lamentations).[35] In 1252, he returned to Paris to study for a master's degree in theology. He lectured on the Bible as an apprentice professor, and upon becoming a baccalaureus Sententiarum (bachelor of the Sentences)[36] he devoted his final three years of study to commenting on Peter Lombard's Sentences. In the first of his four theological syntheses, Thomas composed a massive commentary on the Sentences entitled, Scriptum super libros Sententiarium (Commentary on the Sentences). Aside from his master's writings, he wrote De ente et essentia (On Being and Essence) for his fellow Dominicans in Paris.[21]

In the spring of 1256, Thomas was appointed regent master in theology at Paris and one of his first works upon assuming this office was Contra impugnantes Dei cultum et religionem (Against Those Who Assail the Worship of God and Religion), defending the mendicant orders, which had come under attack by William of Saint-Amour.[37] During his tenure from 1256 to 1259, Thomas wrote numerous works, including: Quaestiones Disputatae de Veritate (Disputed Questions on Truth), a collection of twenty-nine disputed questions on aspects of faith and the human condition[38] prepared for the public university debates he presided over during Lent and Advent;[39] Quaestiones quodlibetales (Quodlibetal Questions), a collection of his responses to questions de quodlibet posed to him by the academic audience;[38] and both Expositio super librum Boethii De trinitate (Commentary on Boethius's De trinitate) and Expositio super librum Boethii De hebdomadibus (Commentary on Boethius's De hebdomadibus), commentaries on the works of 6th-century Roman philosopher Boethius.[40] By the end of his regency, Thomas was working on one of his most famous works, Summa contra Gentiles.[41]

Naples, Orvieto, Rome (1259–1268)

In 1259, Thomas completed his first regency at the studium generale and left Paris so that others in his order could gain this teaching experience. He returned to Naples where he was appointed as general preacher by the provincial chapter of 29 September 1260. In September 1261 he was called to Orvieto as conventual lector, where he was responsible for the pastoral formation of the friars unable to attend a studium generale. In Orvieto, Thomas completed his Summa contra Gentiles, wrote the Catena aurea (The Golden Chain),[42] and produced works for Pope Urban IV such as the liturgy for the newly created feast of Corpus Christi and the Contra errores graecorum (Against the Errors of the Greeks).[41] Some of the hymns that Thomas wrote for the feast of Corpus Christi are still sung today, such as the Pange lingua (whose final two verses are the famous Tantum ergo), and Panis angelicus. Modern scholarship has confirmed that Thomas was indeed the author of these texts, a point that some had contested.[43]

In February 1265, the newly elected Pope Clement IV summoned Thomas to Rome to serve as papal theologian. This same year, he was ordered by the Dominican Chapter of Agnani[44] to teach at the studium conventuale at the Roman convent of Santa Sabina, founded in 1222.[45] The studium at Santa Sabina now became an experiment for the Dominicans, the Order's first studium provinciale, an intermediate school between the studium conventuale and the studium generale. Prior to this time, the Roman Province had offered no specialized education of any sort, no arts, no philosophy; only simple convent schools, with their basic courses in theology for resident friars, were functioning in Tuscany and the meridionale during the first several decades of the order's life. The new studium provinciale at Santa Sabina was to be a more advanced school for the province.[46] Tolomeo da Lucca, an associate and early biographer of Thomas, tells us that at the Santa Sabina studium Thomas taught the full range of philosophical subjects, both moral and natural.[47]

While at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale, Thomas began his most famous work, the Summa Theologiae,[42] which he conceived specifically suited to beginner students: "Because a doctor of Catholic truth ought not only to teach the proficient, but to him pertains also to instruct beginners. As the Apostle says in 1 Corinthians 3:1–2, as to infants in Christ, I gave you milk to drink, not meat, our proposed intention in this work is to convey those things that pertain to the Christian religion in a way that is fitting to the instruction of beginners."[48] While there he also wrote a variety of other works like his unfinished Compendium Theologiae and Responsio ad fr. Ioannem Vercellensem de articulis 108 sumptis ex opere Petri de Tarentasia (Reply to Brother John of Vercelli Regarding 108 Articles Drawn from the Work of Peter of Tarentaise).[40]

In his position as head of the studium, Thomas conducted a series of important disputations on the power of God, which he compiled into his De potentia.[49] Nicholas Brunacci was among Thomas's students at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale and later at the Paris studium generale. In November 1268, he was with Thomas and his associate and secretary Reginald of Piperno as they left Viterbo on their way to Paris to begin the academic year.[50] Another student of Thomas's at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale was Blessed Tommasello da Perugia.[51]

Thomas remained at the studium at Santa Sabina from 1265 until he was called back to Paris in 1268 for a second teaching regency.[49] With his departure for Paris in 1268 and the passage of time, the pedagogical activities of the studium provinciale at Santa Sabina were divided between two campuses. A new convent of the Order at the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva began in 1255 as a community for women converts but grew rapidly in size and importance after being given over to the Dominicans friars in 1275.[45] In 1288, the theology component of the provincial curriculum for the education of the friars was relocated from the Santa Sabina studium provinciale to the studium conventuale at Santa Maria sopra Minerva, which was redesignated as a studium particularis theologiae.[52] This studium was transformed in the 16th century into the College of Saint Thomas (Latin: Collegium Divi Thomæ). In the 20th century, the college was relocated to the convent of Saints Dominic and Sixtus and was transformed into the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum.

Quarrelsome second Paris regency (1269–1272)

In 1268, the Dominican Order assigned Thomas to be regent master at the University of Paris for a second time, a position he held until the spring of 1272. Part of the reason for this sudden reassignment appears to have arisen from the rise of "Averroism" or "radical Aristotelianism" in the universities. In response to these perceived errors, Thomas wrote two works, one of them being De unitate intellectus, contra Averroistas (On the Unity of Intellect, against the Averroists) in which he reprimands Averroism as incompatible with Christian doctrine.[53] During his second regency, he finished the second part of the Summa and wrote De virtutibus and De aeternitate mundi, contra murmurantes (On the Eternity of the World, against Grumblers),[49] the latter of which dealt with controversial Averroist and Aristotelian beginninglessness of the world.[54]

Disputes with some important Franciscans conspired to make his second regency much more difficult and troubled than the first. A year before Thomas re-assumed the regency at the 1266–67 Paris disputations, Franciscan master William of Baglione accused Thomas of encouraging Averroists, most likely counting him as one of the "blind leaders of the blind". Eleonore Stump says, "It has also been persuasively argued that Thomas Aquinas's De aeternitate mundi was directed in particular against his Franciscan colleague in theology, John Pecham."[54]

Thomas was deeply disturbed by the spread of Averroism and was angered when he discovered Siger of Brabant teaching Averroistic interpretations of Aristotle to Parisian students.[55] On 10 December 1270, the Bishop of Paris, Étienne Tempier, issued an edict condemning thirteen Aristotelian and Averroistic propositions as heretical and excommunicating anyone who continued to support them.[56] Many in the ecclesiastical community, the so-called Augustinians, were fearful that this introduction of Aristotelianism and the more extreme Averroism might somehow contaminate the purity of the Christian faith. In what appears to be an attempt to counteract the growing fear of Aristotelian thought, Thomas conducted a series of disputations between 1270 and 1272: De virtutibus in communi (On Virtues in General), De virtutibus cardinalibus (On Cardinal Virtues), and De spe (On Hope).[57]

Late career and cessation of writing (1272–1274)

In 1272, Thomas took leave from the University of Paris when the Dominicans from his home province called upon him to establish a studium generale wherever he liked and staff it as he pleased. He chose to establish the institution in Naples and moved there to take his post as regent master.[49] He took his time at Naples to work on the third part of the Summa while giving lectures on various religious topics. He also preached to the people of Naples every day in Lent of 1273. These sermons on the Commandments, the Creed, the Our Father, and Hail Mary were very popular.[58]

Thomas has been traditionally ascribed with the ability to levitate. For example, G. K. Chesterton wrote that "His experiences included well-attested cases of levitation in ecstasy; and the Blessed Virgin appeared to him, comforting him with the welcome news that he would never be a Bishop."[59]

It is traditionally held that on one occasion, in 1273, at the Dominican convent of Naples in the chapel of Saint Nicholas,[60] after Matins, Thomas lingered and was seen by the sacristan Domenic of Caserta to be levitating in prayer with tears before an icon of the crucified Christ. Christ said to Thomas, "You have written well of me, Thomas. What reward would you have for your labor?" Thomas responded, "Nothing but you, Lord."[61]

On 6 December 1273, another mystical experience took place. While Thomas was celebrating Mass, he experienced an unusually long ecstasy.[62] Because of what he saw, he abandoned his routine and refused to dictate to his socius Reginald of Piperno. When Reginald begged him to get back to work, Thomas replied: "Reginald, I cannot, because all that I have written seems like straw to me"[63] (mihi videtur ut palea).[64] As a result, the Summa Theologica would remain uncompleted.[65] What exactly triggered Thomas's change in behaviour is believed by some to have been some kind of supernatural experience of God.[66] After taking to his bed, however, he did recover some strength.[67]

In 1054, the Great Schism had occurred between the Catholic Church in the West, and the Eastern Orthodox Church. Looking to find a way to reunite the two, Pope Gregory X convened the Second Council of Lyon to be held on 1 May 1274 and summoned Thomas to attend.[68] At the meeting, Thomas's work for Pope Urban IV concerning the Greeks, Contra errores graecorum, was to be presented.[69]

On his way to the council, riding on a donkey along the Appian Way,[68] he struck his head on the branch of a fallen tree and became seriously ill again. He was then quickly escorted to Monte Cassino to convalesce.[67] After resting for a while, he set out again but stopped at the Cistercian Fossanova Abbey after again falling ill.[70] The monks nursed him for several days,[71] and as he received his last rites he prayed: "I have written and taught much about this very holy Body, and about the other sacraments in the faith of Christ, and about the Holy Roman Church, to whose correction I expose and submit everything I have written."[72] He died on 7 March 1274[70] while giving commentary on the Song of Songs.[73]

Legacy, veneration, and modern reception

Condemnation of 1277

In 1277, Étienne Tempier, the same bishop of Paris who had issued the condemnation of 1270, issued another more extensive condemnation. One aim of this condemnation was to clarify that God's absolute power transcended any principles of logic that Aristotle or Averroes might place on it.[74] More specifically, it contained a list of 219 propositions, including twenty Thomistic propositions, that the bishop had determined to violate the omnipotence of God. The inclusion of the Thomistic propositions badly damaged Thomas's reputation for many years.[75]

Canonization

By the 1300s, however, Thomas's theology had begun its rise to prestige. In the Divine Comedy (completed c. 1321), Dante sees the glorified soul of Thomas in the Heaven of the Sun with the other great exemplars of religious wisdom.[76] Dante asserts that Thomas died by poisoning, on the order of Charles of Anjou;[77] Villani cites this belief,[78] and the Anonimo Fiorentino describes the crime and its motive. But the historian Ludovico Antonio Muratori reproduces the account made by one of Thomas's friends, and this version of the story gives no hint of foul play.[79]

When the devil's advocate at his canonization process objected that there were no miracles, one of the cardinals answered, "Tot miraculis, quot articulis"—"there are as many miracles (in his life) as articles (in his Summa)".[80] Fifty years after Thomas's death, on 18 July 1323, Pope John XXII, seated in Avignon, pronounced Thomas a saint.[81]

A monastery at Naples, near Naples Cathedral, shows a cell in which he supposedly lived.[79] His remains were translated from Fossanova to the Church of the Jacobins in Toulouse on 28 January 1369. Between 1789 and 1974, they were held in the Basilica of Saint-Sernin. In 1974, they were returned to the Church of the Jacobins, where they have remained ever since.

When he was canonized, his feast day was inserted in the General Roman Calendar for celebration on 7 March, the day of his death. Since this date commonly falls within Lent, the 1969 revision of the calendar moved his memorial to 28 January, the date of the translation of his relics to Church of the Jacobins, Toulouse.[82][83]

Thomas Aquinas is honored with a feast day in some churches of the Anglican Communion with a Lesser Festival on 28 January.[84]

The Catholic Church honours Thomas Aquinas as a saint and regards him as the model teacher for those studying for the priesthood. In modern times, under papal directives, the study of his works was long used as a core of the required program of study for those seeking ordination as priests or deacons, as well as for those in religious formation and for other students of the sacred disciplines (philosophy, Catholic theology, church history, liturgy, and canon law).[85]

Doctor of the Church

Pope Pius V proclaimed St. Thomas Aquinas a Doctor of the Church on 15 April 1567, [86] and ranked his feast with those of the four great Latin fathers: Ambrose, Augustine of Hippo, Jerome and Gregory.[79] At the Council of Trent, Thomas had the honour of having his Summa Theologiae placed on the altar alongside the Bible and the Decretals.[75][80]

In his encyclical of 4 August 1879, Aeterni Patris, Pope Leo XIII stated that Thomas Aquinas's theology was a definitive exposition of Catholic doctrine. Thus, he directed the clergy to take the teachings of Thomas as the basis of their theological positions. Leo XIII also decreed that all Catholic seminaries and universities must teach Thomas's doctrines, and where Thomas did not speak on a topic, the teachers were "urged to teach conclusions that were reconcilable with his thinking." In 1880, Thomas Aquinas was declared the patron saint of all Catholic educational establishments.[79]

On 29 June 1923, on the VI centenary of his canonisation, Pope Pius XI dedicated the encyclical Studiorum Ducem to him.

The Second Vatican Council, with the decree Optatam Totius (on the formation of priests, at No. 15), proposed an authentic interpretation of the popes' teaching on Thomism, requiring that the theological formation of priests be done with Thomas Aquinas as teacher.[87]

The encyclical Fides et ratio of Pope John Paul II described Thomas as "a master of thought and a model of the right way to do theology".[88]

Pope Benedict XV declared: "This (Dominican) Order ... acquired new luster when the Church declared the teaching of Thomas to be her own and that Doctor, honoured with the special praises of the Pontiffs, the master and patron of Catholic schools."[89]

Modern influence

Some modern ethicists within the Catholic Church (notably Alasdair MacIntyre) and outside it (notably Philippa Foot) have recently commented on the possible use of Thomas's virtue ethics as a way of avoiding utilitarianism or Kantian "sense of duty" (called deontology).[90] Through the work of twentieth-century philosophers such as Elizabeth Anscombe (especially in her book Intention), Thomas's principle of double effect specifically and his theory of intentional activity generally have been influential.[citation needed]

The cognitive neuroscientist Walter Freeman has proposed that Thomism is the philosophical system explaining cognition that is most compatible with neurodynamics.[91]

Henry Adams's Mont Saint Michel and Chartres ends with a culminating chapter on Thomas, in which Adams calls Thomas an "artist" and constructs an extensive analogy between the design of Thomas's "Church Intellectual" and that of the gothic cathedrals of that period. Erwin Panofsky later would echo these views in Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism (1951).[citation needed]

Thomas's aesthetic theories, especially the concept of claritas, deeply influenced the literary practice of modernist writer James Joyce, who used to extol Thomas as being second only to Aristotle among Western philosophers. Joyce refers to Thomas's doctrines in Elementa philosophiae ad mentem D. Thomae Aquinatis doctoris angelici (1898) of Girolamo Maria Mancini, professor of theology at the Collegium Divi Thomae de Urbe.[92] For example, Mancini's Elementa is referred to in Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.[93]

The influence of Thomas's aesthetics also can be found in the works of the Italian semiotician Umberto Eco, who wrote an essay on aesthetic ideas in Thomas (published in 1956 and republished in 1988 in a revised edition).[94]

Modern criticism

Twentieth-century philosopher Bertrand Russell criticized Thomas's philosophy, stating that:

He does not, like the Platonic Socrates, set out to follow wherever the argument may lead. He is not engaged in an inquiry, the result of which it is impossible to know in advance. Before he begins to philosophize, he already knows the truth; it is declared in the Catholic faith. If he can find apparently rational arguments for some parts of the faith, so much the better; if he cannot, he need only fall back on revelation. The finding of arguments for a conclusion given in advance is not philosophy, but special pleading. I cannot, therefore, feel that he deserves to be put on a level with the best philosophers either of Greece or of modern times.[95]

This criticism is illustrated with the following example: according to Russell, Thomas advocates the indissolubility of marriage "on the ground that the father is useful in the education of the children, (a) because he is more rational than the mother, (b) because, being stronger, he is better able to inflict physical punishment."[96] Even though modern approaches to education do not support these views, "No follower of Saint Thomas would, on that account, cease to believe in lifelong monogamy, because the real grounds of belief are not those which are alleged".[96]

Theology

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|