A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Disability |

|---|

|

|

In medicine, a prosthesis (pl.: prostheses; from Ancient Greek: πρόσθεσις, romanized: prósthesis, lit. 'addition, application, attachment'),[1] or a prosthetic implant,[2][3] is an artificial device that replaces a missing body part, which may be lost through physical trauma, disease, or a condition present at birth (congenital disorder). Prostheses are intended to restore the normal functions of the missing body part.[4] Amputee rehabilitation is primarily coordinated by a physiatrist as part of an inter-disciplinary team consisting of physiatrists, prosthetists, nurses, physical therapists, and occupational therapists.[5] Prostheses can be created by hand or with computer-aided design (CAD), a software interface that helps creators design and analyze the creation with computer-generated 2-D and 3-D graphics as well as analysis and optimization tools.[6]

Types

A person's prosthesis should be designed and assembled according to the person's appearance and functional needs. For instance, a person may need a transradial prosthesis, but the person needs to choose between an aesthetic functional device, a myoelectric device, a body-powered device, or an activity specific device. The person's future goals and economical capabilities may help them choose between one or more devices.

Craniofacial prostheses include intra-oral and extra-oral prostheses. Extra-oral prostheses are further divided into hemifacial, auricular (ear), nasal, orbital and ocular. Intra-oral prostheses include dental prostheses, such as dentures, obturators, and dental implants.

Prostheses of the neck include larynx substitutes, trachea and upper esophageal replacements,

Somato prostheses of the torso include breast prostheses which may be either single or bilateral, full breast devices or nipple prostheses.

Penile prostheses are used to treat erectile dysfunction, correct penile deformity, perform phalloplasty procedures in cisgender men, and to build a new penis in female-to-male gender reassignment surgeries.

Limb prostheses

Limb prostheses include both upper- and lower-extremity prostheses.

Upper-extremity prostheses are used at varying levels of amputation: forequarter, shoulder disarticulation, transhumeral prosthesis, elbow disarticulation, transradial prosthesis, wrist disarticulation, full hand, partial hand, finger, partial finger. A transradial prosthesis is an artificial limb that replaces an arm missing below the elbow.

Upper limb prostheses can be categorized in three main categories: Passive devices, Body Powered devices, and Externally Powered (myoelectric) devices. Passive devices can either be passive hands, mainly used for cosmetic purposes, or passive tools, mainly used for specific activities (e.g. leisure or vocational). An extensive overview and classification of passive devices can be found in a literature review by Maat et.al.[7] A passive device can be static, meaning the device has no movable parts, or it can be adjustable, meaning its configuration can be adjusted (e.g. adjustable hand opening). Despite the absence of active grasping, passive devices are very useful in bimanual tasks that require fixation or support of an object, or for gesticulation in social interaction. According to scientific data a third of the upper limb amputees worldwide use a passive prosthetic hand.[7] Body Powered or cable-operated limbs work by attaching a harness and cable around the opposite shoulder of the damaged arm. A recent body-powered approach has explored the utilization of the user's breathing to power and control the prosthetic hand to help eliminate actuation cable and harness.[8][9][10] The third category of available prosthetic devices comprises myoelectric arms. This particular class of devices distinguishes itself from the previous ones due to the inclusion of a battery system. This battery serves the dual purpose of providing energy for both actuation and sensing components. While actuation predominantly relies on motor or pneumatic systems,[11] a variety of solutions have been explored for capturing muscle activity, including techniques such as Electromyography, Sonomyography, Myokinetic, and others.[12][13][14] These methods function by detecting the minute electrical currents generated by contracted muscles during upper arm movement, typically employing electrodes or other suitable tools. Subsequently, these acquired signals are converted into gripping patterns or postures that the artificial hand will then execute.

In the prosthetics industry, a trans-radial prosthetic arm is often referred to as a "BE" or below elbow prosthesis.

Lower-extremity prostheses provide replacements at varying levels of amputation. These include hip disarticulation, transfemoral prosthesis, knee disarticulation, transtibial prosthesis, Syme's amputation, foot, partial foot, and toe. The two main subcategories of lower extremity prosthetic devices are trans-tibial (any amputation transecting the tibia bone or a congenital anomaly resulting in a tibial deficiency) and trans-femoral (any amputation transecting the femur bone or a congenital anomaly resulting in a femoral deficiency).[citation needed]

A transfemoral prosthesis is an artificial limb that replaces a leg missing above the knee. Transfemoral amputees can have a very difficult time regaining normal movement. In general, a transfemoral amputee must use approximately 80% more energy to walk than a person with two whole legs.[15] This is due to the complexities in movement associated with the knee. In newer and more improved designs, hydraulics, carbon fiber, mechanical linkages, motors, computer microprocessors, and innovative combinations of these technologies are employed to give more control to the user. In the prosthetics industry, a trans-femoral prosthetic leg is often referred to as an "AK" or above the knee prosthesis.

A transtibial prosthesis is an artificial limb that replaces a leg missing below the knee. A transtibial amputee is usually able to regain normal movement more readily than someone with a transfemoral amputation, due in large part to retaining the knee, which allows for easier movement. Lower extremity prosthetics describe artificially replaced limbs located at the hip level or lower. In the prosthetics industry, a trans-tibial prosthetic leg is often referred to as a "BK" or below the knee prosthesis.

Prostheses are manufactured and fit by clinical Prosthetists. Prosthetists are healthcare professionals responsible for making, fitting, and adjusting prostheses and for lower limb prostheses will assess both gait and prosthetic alignment. Once a prosthesis has been fit and adjusted by a Prosthetist, a rehabilitation Physiotherapist (called Physical Therapist in America) will help teach a new prosthetic user to walk with a leg prosthesis. To do so, the physical therapist may provide verbal instructions and may also help guide the person using touch or tactile cues. This may be done in a clinic or home. There is some research suggesting that such training in the home may be more successful if the treatment includes the use of a treadmill.[16] Using a treadmill, along with the physical therapy treatment, helps the person to experience many of the challenges of walking with a prosthesis.

In the United Kingdom, 75% of lower limb amputations are performed due to inadequate circulation (dysvascularity).[17] This condition is often associated with many other medical conditions (co-morbidities) including diabetes and heart disease that may make it a challenge to recover and use a prosthetic limb to regain mobility and independence.[17] For people who have inadequate circulation and have lost a lower limb, there is insufficient evidence due to a lack of research, to inform them regarding their choice of prosthetic rehabilitation approaches.[17]

Lower extremity prostheses are often categorized by the level of amputation or after the name of a surgeon:[18][19]

- Transfemoral (Above-knee)

- Transtibial (Below-knee)

- Ankle disarticulation (more commonly known as Syme's amputation)

- Knee disarticulation

- Hip disarticulation

- Hemi-pelvictomy

- Partial foot amputations (Pirogoff, Talo-Navicular and Calcaneo-cuboid (Chopart), Tarso-metatarsal (Lisfranc), Trans-metatarsal, Metatarsal-phalangeal, Ray amputations, toe amputations).[19]

- Van Nes rotationplasty

Prosthetic raw materials

Prosthetic are made lightweight for better convenience for the amputee. Some of these materials include:

- Plastics:

- Polyethylene

- Polypropylene

- Acrylics

- Polyurethane

- Wood (early prosthetics)

- Rubber (early prosthetics)

- Lightweight metals:

- Titanium

- Aluminum

- Composites:

- Carbon fiber reinforced polymers[4]

Wheeled prostheses have also been used extensively in the rehabilitation of injured domestic animals, including dogs, cats, pigs, rabbits, and turtles.[20]

History

Prosthetics originate from the ancient Near East circa 3000 BCE, with the earliest evidence of prosthetics appearing in ancient Egypt and Iran. The earliest recorded mention of eye prosthetics is from the Egyptian story of the Eye of Horus dates circa 3000 BC, which involves the left eye of Horus being plucked out and then restored by Thoth. Circa 3000-2800 BC, the earliest archaeological evidence of prosthetics is found in ancient Iran, where an eye prosthetic is found buried with a woman in Shahr-i Shōkhta. It was likely made of bitumen paste that was covered with a thin layer of gold.[21] The Egyptians were also early pioneers of foot prosthetics, as shown by the wooden toe found on a body from the New Kingdom circa 1000 BC.[22] Another early textual mention is found in South Asia circa 1200 BC, involving the warrior queen Vishpala in the Rigveda.[23] Roman bronze crowns have also been found, but their use could have been more aesthetic than medical.[24]

An early mention of a prosthetic comes from the Greek historian Herodotus, who tells the story of Hegesistratus, a Greek diviner who cut off his own foot to escape his Spartan captors and replaced it with a wooden one.[25]

Wood and metal prosthetics

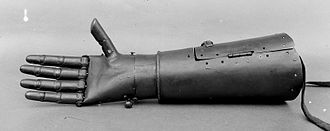

Pliny the Elder also recorded the tale of a Roman general, Marcus Sergius, whose right hand was cut off while campaigning and had an iron hand made to hold his shield so that he could return to battle. A famous and quite refined[27] historical prosthetic arm was that of Götz von Berlichingen, made at the beginning of the 16th century. The first confirmed use of a prosthetic device, however, is from 950 to 710 BC. In 2000, research pathologists discovered a mummy from this period buried in the Egyptian necropolis near ancient Thebes that possessed an artificial big toe. This toe, consisting of wood and leather, exhibited evidence of use. When reproduced by bio-mechanical engineers in 2011, researchers discovered that this ancient prosthetic enabled its wearer to walk both barefoot and in Egyptian style sandals. Previously, the earliest discovered prosthetic was an artificial leg from Capua.[28]

Around the same time, François de la Noue is also reported to have had an iron hand, as is, in the 17th century, René-Robert Cavalier de la Salle.[29] Henri de Tonti had a prosthetic hook for a hand. During the Middle Ages, prosthetics remained quite basic in form. Debilitated knights would be fitted with prosthetics so they could hold up a shield, grasp a lance or a sword, or stabilize a mounted warrior.[30] Only the wealthy could afford anything that would assist in daily life.[31]

One notable prosthesis was that belonging to an Italian man, who scientists estimate replaced his amputated right hand with a knife.[32][33] Scientists investigating the skeleton, which was found in a Longobard cemetery in Povegliano Veronese, estimated that the man had lived sometime between the 6th and 8th centuries AD.[34][33] Materials found near the man's body suggest that the knife prosthesis was attached with a leather strap, which he repeatedly tightened with his teeth.[34]

During the Renaissance, prosthetics developed with the use of iron, steel, copper, and wood. Functional prosthetics began to make an appearance in the 1500s.[35]

Technology progress before the 20th century

An Italian surgeon recorded the existence of an amputee who had an arm that allowed him to remove his hat, open his purse, and sign his name.[36] Improvement in amputation surgery and prosthetic design came at the hands of Ambroise Paré. Among his inventions was an above-knee device that was a kneeling peg leg and foot prosthesis with a fixed position, adjustable harness, and knee lock control. The functionality of his advancements showed how future prosthetics could develop.

Other major improvements before the modern era:

- Pieter Verduyn – First non-locking below-knee (BK) prosthesis.

- James Potts – Prosthesis made of a wooden shank and socket, a steel knee joint and an articulated foot that was controlled by catgut tendons from the knee to the ankle. Came to be known as "Anglesey Leg" or "Selpho Leg".

- Sir James Syme – A new method of ankle amputation that did not involve amputating at the thigh.

- Benjamin Palmer – Improved upon the Selpho leg. Added an anterior spring and concealed tendons to simulate natural-looking movement.

- Dubois Parmlee – Created prosthetic with a suction socket, polycentric knee, and multi-articulated foot.

- Marcel Desoutter & Charles Desoutter – First aluminium prosthesis[37]

- Henry Heather Bigg, and his son Henry Robert Heather Bigg, won the Queen's command to provide "surgical appliances" to wounded soldiers after Crimea War. They developed arms that allowed a double arm amputee to crochet, and a hand that felt natural to others based on ivory, felt and leather.[38]

At the end of World War II, the NAS (National Academy of Sciences) began to advocate better research and development of prosthetics. Through government funding, a research and development program was developed within the Army, Navy, Air Force, and the Veterans Administration.

Lower extremity modern history

After the Second World War a team at the University of California, Berkeley including James Foort and C.W. Radcliff helped to develop the quadrilateral socket by developing a jig fitting system for amputations above the knee. Socket technology for lower extremity limbs saw a further revolution during the 1980s when John Sabolich C.P.O., invented the Contoured Adducted Trochanteric-Controlled Alignment Method (CATCAM) socket, later to evolve into the Sabolich Socket. He followed the direction of Ivan Long and Ossur Christensen as they developed alternatives to the quadrilateral socket, which in turn followed the open ended plug socket, created from wood.[39] The advancement was due to the difference in the socket to patient contact model. Prior to this, sockets were made in the shape of a square shape with no specialized containment for muscular tissue. New designs thus help to lock in the bony anatomy, locking it into place and distributing the weight evenly over the existing limb as well as the musculature of the patient. Ischial containment is well known and used today by many prosthetist to help in patient care. Variations of the ischial containment socket thus exists and each socket is tailored to the specific needs of the patient. Others who contributed to socket development and changes over the years include Tim Staats, Chris Hoyt, and Frank Gottschalk. Gottschalk disputed the efficacy of the CAT-CAM socket- insisting the surgical procedure done by the amputation surgeon was most important to prepare the amputee for good use of a prosthesis of any type socket design.[40]

The first microprocessor-controlled prosthetic knees became available in the early 1990s. The Intelligent Prosthesis was the first commercially available microprocessor-controlled prosthetic knee. It was released by Chas. A. Blatchford & Sons, Ltd., of Great Britain, in 1993 and made walking with the prosthesis feel and look more natural.[41] An improved version was released in 1995 by the name Intelligent Prosthesis Plus. Blatchford released another prosthesis, the Adaptive Prosthesis, in 1998. The Adaptive Prosthesis utilized hydraulic controls, pneumatic controls, and a microprocessor to provide the amputee with a gait that was more responsive to changes in walking speed. Cost analysis reveals that a sophisticated above-knee prosthesis will be about $1 million in 45 years, given only annual cost of living adjustments.[42]

In 2019, a project under AT2030 was launched in which bespoke sockets are made using a thermoplastic, rather than through a plaster cast. This is faster to do and significantly less expensive. The sockets were called Amparo Confidence sockets.[43][44]

Upper extremity modern history

In 2005, DARPA started the Revolutionizing Prosthetics program.[45][46][47][48][49][50]

Design Trends Moving Forward

There are many steps in the evolution of prosthetic design trends that are moving forward with time. Many design trends point to lighter, more durable, and flexible materials like carbon fiber, silicone, and advanced polymers. These not only make the prosthetic limb lighter and more durable but also allow it to mimic the look and feel of natural skin, providing users with a more comfortable and natural experience.[51] This new technology helps prosthetic users blend in with people with normal ligaments to reduce the stigmatism for people who wear prosthetics. Another trend points towards using bionics and myoelectric components in prosthetic design. These limbs utilize sensors to detect electrical signals from the user’s residual muscles. The signals are then converted into motions, allowing users to control their prosthetic limbs using their own muscle contractions. This has greatly improved the range and fluidity of movements available to amputees, making tasks like grasping objects or walking naturally much more feasible.[51] Integration with AI is also on the forefront to the prosthetic design. AI-enabled prosthetic limbs can learn and adapt to the user’s habits and preferences over time, ensuring optimal functionality. By analyzing the user’s gait, grip, and other movements, these smart limbs can make real-time adjustments, providing smoother and more natural motions.[51]

Patient procedure

A prosthesis is a functional replacement for an amputated or congenitally malformed or missing limb. Prosthetists are responsible for the prescription, design, and management of a prosthetic device.

In most cases, the prosthetist begins by taking a plaster cast of the patient's affected limb. Lightweight, high-strength thermoplastics are custom-formed to this model of the patient. Cutting-edge materials such as carbon fiber, titanium and Kevlar provide strength and durability while making the new prosthesis lighter. More sophisticated prostheses are equipped with advanced electronics, providing additional stability and control.[52]

Current technology and manufacturing

Over the years, there have been advancements in artificial limbs. New plastics and other materials, such as carbon fiber, have allowed artificial limbs to be stronger and lighter, limiting the amount of extra energy necessary to operate the limb. This is especially important for trans-femoral amputees. Additional materials have allowed artificial limbs to look much more realistic, which is important to trans-radial and transhumeral amputees because they are more likely to have the artificial limb exposed.[53]

In addition to new materials, the use of electronics has become very common in artificial limbs. Myoelectric limbs, which control the limbs by converting muscle movements to electrical signals, have become much more common than cable operated limbs. Myoelectric signals are picked up by electrodes, the signal gets integrated and once it exceeds a certain threshold, the prosthetic limb control signal is triggered which is why inherently, all myoelectric controls lag. Conversely, cable control is immediate and physical, and through that offers a certain degree of direct force feedback that myoelectric control does not. Computers are also used extensively in the manufacturing of limbs. Computer Aided Design and Computer Aided Manufacturing are often used to assist in the design and manufacture of artificial limbs.[53][54]

Most modern artificial limbs are attached to the residual limb (stump) of the amputee by belts and cuffs or by suction. The residual limb either directly fits into a socket on the prosthetic, or—more commonly today—a liner is used that then is fixed to the socket either by vacuum (suction sockets) or a pin lock. Liners are soft and by that, they can create a far better suction fit than hard sockets. Silicone liners can be obtained in standard sizes, mostly with a circular (round) cross section, but for any other residual limb shape, custom liners can be made. The socket is custom made to fit the residual limb and to distribute the forces of the artificial limb across the area of the residual limb (rather than just one small spot), which helps reduce wear on the residual limb.

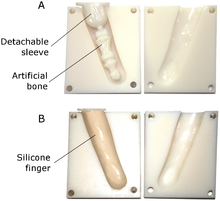

Production of prosthetic socket

The production of a prosthetic socket begins with capturing the geometry of the residual limb, this process is called shape capture. The goal of this process is to create an accurate representation of the residual limb, which is critical to achieve good socket fit.[55] The custom socket is created by taking a plaster cast of the residual limb or, more commonly today, of the liner worn over their residual limb, and then making a mold from the plaster cast. The commonly used compound is called Plaster of Paris.[56] In recent years, various digital shape capture systems have been developed which can be input directly to a computer allowing for a more sophisticated design. In general, the shape capturing process begins with the digital acquisition of three-dimensional (3D) geometric data from the amputee's residual limb. Data are acquired with either a probe, laser scanner, structured light scanner, or a photographic-based 3D scanning system.[57]

After shape capture, the second phase of the socket production is called rectification, which is the process of modifying the model of the residual limb by adding volume to bony prominence and potential pressure points and remove volume from load bearing area. This can be done manually by adding or removing plaster to the positive model, or virtually by manipulating the computerized model in the software.[58] Lastly, the fabrication of the prosthetic socket begins once the model has been rectified and finalized. The prosthetists would wrap the positive model with a semi-molten plastic sheet or carbon fiber coated with epoxy resin to construct the prosthetic socket.[55] For the computerized model, it can be 3D printed using a various of material with different flexibility and mechanical strength.[59]

Optimal socket fit between the residual limb and socket is critical to the function and usage of the entire prosthesis. If the fit between the residual limb and socket attachment is too loose, this will reduce the area of contact between the residual limb and socket or liner, and increase pockets between residual limb skin and socket or liner. Pressure then is higher, which can be painful. Air pockets can allow sweat to accumulate that can soften the skin. Ultimately, this is a frequent cause for itchy skin rashes. Over time, this can lead to breakdown of the skin.[15] On the other hand, a very tight fit may excessively increase the interface pressures that may also lead to skin breakdown after prolonged use.[60]

Artificial limbs are typically manufactured using the following steps:[53]

- Measurement of the residual limb

- Measurement of the body to determine the size required for the artificial limb

- Fitting of a silicone liner

- Creation of a model of the liner worn over the residual limb

- Formation of thermoplastic sheet around the model – This is then used to test the fit of the prosthetic

- Formation of permanent socket

- Formation of plastic parts of the artificial limb – Different methods are used, including vacuum forming and injection molding

- Creation of metal parts of the artificial limb using die casting

- Assembly of entire limb

Body-powered arms

Current technology allows body-powered arms to weigh around one-half to one-third of what a myoelectric arm does.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=ProsthesesText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk