A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Elephants Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

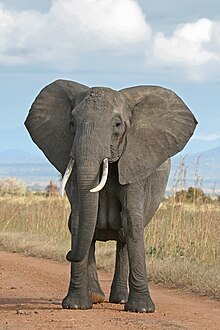

| A female African bush elephant in Mikumi National Park, Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Superfamily: | Elephantoidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Groups included | |

| |

| |

| Distribution of living elephant species | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

| |

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana), the African forest elephant (L. cyclotis), and the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae and the order Proboscidea; extinct relatives include mammoths and mastodons. Distinctive features of elephants include a long proboscis called a trunk, tusks, large ear flaps, pillar-like legs, and tough but sensitive grey skin. The trunk is prehensile, bringing food and water to the mouth and grasping objects. Tusks, which are derived from the incisor teeth, serve both as weapons and as tools for moving objects and digging. The large ear flaps assist in maintaining a constant body temperature as well as in communication. African elephants have larger ears and concave backs, whereas Asian elephants have smaller ears and convex or level backs.

Elephants are scattered throughout sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia and are found in different habitats, including savannahs, forests, deserts, and marshes. They are herbivorous, and they stay near water when it is accessible. They are considered to be keystone species, due to their impact on their environments. Elephants have a fission–fusion society, in which multiple family groups come together to socialise. Females (cows) tend to live in family groups, which can consist of one female with her calves or several related females with offspring. The leader of a female group, usually the oldest cow, is known as the matriarch.

Males (bulls) leave their family groups when they reach puberty and may live alone or with other males. Adult bulls mostly interact with family groups when looking for a mate. They enter a state of increased testosterone and aggression known as musth, which helps them gain dominance over other males as well as reproductive success. Calves are the centre of attention in their family groups and rely on their mothers for as long as three years. Elephants can live up to 70 years in the wild. They communicate by touch, sight, smell, and sound; elephants use infrasound and seismic communication over long distances. Elephant intelligence has been compared with that of primates and cetaceans. They appear to have self-awareness, and possibly show concern for dying and dead individuals of their kind.

African bush elephants and Asian elephants are listed as endangered and African forest elephants as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). One of the biggest threats to elephant populations is the ivory trade, as the animals are poached for their ivory tusks. Other threats to wild elephants include habitat destruction and conflicts with local people. Elephants are used as working animals in Asia. In the past, they were used in war; today, they are often controversially put on display in zoos, or employed for entertainment in circuses. Elephants have an iconic status in human culture, and have been widely featured in art, folklore, religion, literature, and popular culture.

Etymology

The word elephant is based on the Latin elephas (genitive elephantis) 'elephant', which is the Latinised form of the ancient Greek ἐλέφας (elephas) (genitive ἐλέφαντος (elephantos[1])), probably from a non-Indo-European language, likely Phoenician.[2] It is attested in Mycenaean Greek as e-re-pa (genitive e-re-pa-to) in Linear B syllabic script.[3][4] As in Mycenaean Greek, Homer used the Greek word to mean ivory, but after the time of Herodotus, it also referred to the animal.[1] The word elephant appears in Middle English as olyfaunt (c. 1300) and was borrowed from Old French oliphant (12th century).[2]

Taxonomy

| A cladogram of the elephants within Afrotheria based on molecular evidence[5] |

Elephants belong to the family Elephantidae, the sole remaining family within the order Proboscidea. Their closest extant relatives are the sirenians (dugongs and manatees) and the hyraxes, with which they share the clade Paenungulata within the superorder Afrotheria.[6] Elephants and sirenians are further grouped in the clade Tethytheria.[7]

Three species of living elephants are recognised; the African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana), forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) and Asian elephant (Elephas maximus).[8] African elephants were traditionally considered a single species, Loxodonta africana, but molecular studies have affirmed their status as separate species.[9][10][11] Mammoths (Mammuthus) are nested within living elephants as they are more closely related to Asian elephants than to African elephants.[12] Another extinct genus of elephant, Palaeoloxodon, is also recognised, which appears to have close affinities with African elephants and to have hybridised with African forest elephants.[13]

Evolution

Over 180 extinct members of order Proboscidea have been described.[14] The earliest proboscideans, the African Eritherium and Phosphatherium are known from the late Paleocene.[15] The Eocene included Numidotherium, Moeritherium and Barytherium from Africa. These animals were relatively small and, some, like Moeritherium and Barytherium were probably amphibious.[16][17] Later on, genera such as Phiomia and Palaeomastodon arose; the latter likely inhabited more forested areas. Proboscidean diversification changed little during the Oligocene.[16] One notable species of this epoch was Eritreum melakeghebrekristosi of the Horn of Africa, which may have been an ancestor to several later species.[18]

| |||||||||

| Proboscidea phylogeny based on morphological and DNA evidence[19][20][13] |

A major event in proboscidean evolution was the collision of Afro-Arabia with Eurasia, during the Early Miocene, around 18–19 million years ago, allowing proboscideans to disperse from their African homeland across Eurasia and later, around 16–15 million years ago into North America across the Bering Land Bridge. Proboscidean groups prominent during the Miocene include the deinotheres, along with the more advanced elephantimorphs, including mammutids (mastodons), gomphotheres, amebelodontids (which includes the "shovel tuskers" like Platybelodon), choerolophodontids and stegodontids.[21] Around 10 million years ago, the earliest members of the family Elephantidae emerged in Africa, having originated from gomphotheres.[22]

Elephantids are distinguished from earlier proboscideans by a major shift in the molar morphology to parallel lophs rather than the cusps of earlier proboscideans, allowing them to become higher-crowned (hypsodont) and more efficient in consuming grass.[23] The Late Miocene saw major climactic changes, which resulted in the decline and extinction of many proboscidean groups.[21] The earliest members of the modern genera of Elephantidae appeared during the latest Miocene–early Pliocene around 5 million years ago. The elephantid genera Elephas (which includes the living Asian elephant) and Mammuthus (mammoths) migrated out of Africa during the late Pliocene, around 3.6 to 3.2 million years ago.[24]

Over the course of the Early Pleistocene, all non-elephantid probobscidean genera outside of the Americas became extinct with the exception of Stegodon,[21] with gomphotheres dispersing into South America as part of the Great American interchange,[25] and mammoths migrating into North America around 1.5 million years ago.[26] At the end of the Early Pleistocene, around 800,000 years ago the elephantid genus Palaeoloxodon dispersed outside of Africa, becoming widely distributed in Eurasia.[27] Proboscideans were represented by around 23 species at the beginning of the Late Pleistocene. Proboscideans underwent a dramatic decline during the Late Pleistocene as part of the Late Pleistocene extinctions of most large mammals globally, with all remaining non-elephantid proboscideans (including Stegodon, mastodons, and the American gomphotheres Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon) and Palaeoloxodon becoming extinct, with mammoths only surviving in relict populations on islands around the Bering Strait into the Holocene, with their latest survival being on Wrangel Island, where they persisted until around 4,000 years ago.[21][28]

Over the course of their evolution, probobscideans grew in size. With that came longer limbs and wider feet with a more digitigrade stance, along with a larger head and shorter neck. The trunk evolved and grew longer to provide reach. The number of premolars, incisors, and canines decreased, and the cheek teeth (molars and premolars) became longer and more specialised. The incisors developed into tusks of different shapes and sizes.[29] Several species of proboscideans became isolated on islands and experienced insular dwarfism,[30] some dramatically reducing in body size, such as the 1 metre (3.3 ft) tall dwarf elephant species Palaeoloxodon falconeri.[31]