A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Colombo, the financial centre of Sri Lanka | |

| Currency | Sri Lankan rupee (LKR) (Rs// =) (රු) (ரூ) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year | |

Trade organisations | WTO, WCO, SAFTA, IOR-ARC, SCO, BIMSTEC, AIIB and others |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | [5] |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

Population below poverty line |

|

| 39.8 medium (2016, World Bank)[10] | |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Main industries | textiles & clothing, tourism, telecommunications, information technology services, banking, shipping, petroleum refining, construction and processing of tea, rubber, coconuts, tobacco and other agricultural commodities |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | textiles and apparel, tea and spices, electronics, IT services, rubber manufactures, fish, precious stones |

Main export partners | |

| Imports | |

Import goods | Mineral fuels including petroleum product (12.3%) Machinery including computers (9%) Electrical machinery, equipment Vehicles (7.1%) Textile fabric (5%) Plastics (3.7%) Cotton (3.3%) Heavy metals (3%) Ships and boats (2.8%) Iron, steel, aluminium (2.8%) |

Main import partners | |

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| −11.1% (of GDP) (2020 prov.)[19] | |

| Revenues | Rs1,890bn/US$10.4bn (2019 prov.)[20] |

| Expenses | Rs2,915bn/US$16.0bn (2019 prov.)[20] |

| Standard & Poor's:[21]

CC (Fx) Outlook: Negative Moody's:[22] Caa2 Outlook: Stable Fitch:[23] C Outlook: None at this level | |

| |

The mixed economy of Sri Lanka was worth $84 billion by nominal gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019[25] and $296.959 billion by purchasing power parity (PPP).[26] The country had experienced an annual growth of 6.4 percent from 2003 to 2012, well above its regional peers. This growth was driven by the growth of non-tradable sectors, which the World Bank warned to be both unsustainable and unequitable. Growth has slowed since then. In 2019 with an income per capita of 13,620 PPP Dollars[27] or 3,852 (2019) nominal US dollars,[28][29] Sri Lanka was re-classified as a lower middle income nation with the population around 22 million (2021)[30] by the World Bank from a previous upper middle income status.[31]

Sri Lanka has met the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) target of halving extreme poverty and is on track to meet most of the other MDGs, outperforming other South Asian countries. Sri Lanka's poverty headcount index was 4.1% by 2016. Since the end of the three-decade-long Sri Lankan Civil War, Sri Lanka has begun focusing on long-term strategic and structural development challenges, and has financed several infrastructure projects.

High foreign debt, economic mismanagement under the governments of Gotabhaya and Mahinda Rajapaksa,[32] and lower tourism revenue led to the country defaulting on its sovereign debt in April 2022.[33] The economy contracted 7.8% in 2022, and the percentage of the population earning less than $3.65 a day doubled to around 25% of the population. On March 20, 2023, the IMF has loaned US$3 billion to the country as part of a 48-month debt relief program.[34]

Overview

Services accounted for 58.2% of Sri Lanka's economy in 2019 up from 54.6% in 2010, industry 27.4% up from 26.4% a decade earlier and agriculture 7.4%.[8] Though there is a competitive export agricultural sector, technological advances have been slow to enter the protected domestic sector.[35] Sri Lanka is the largest solid and industrial tyres manufacturing centre in the world and has an apparel sector which is moving up the value chain.[36] But rising trade protection over the past decade has also caused concern over the resurgence of inward looking policies.[37]

In services, ports and airports generate income for the country's newfound status as a shipping and aviation hub.[38] Port of Colombo is the largest transhipment hub in South Asia.[39] There is a growing software and information technology sector, which is competitive and is open to global competition.[40] Tourism is a fast expanding area. Lonely Planet named Sri Lanka the best destination to visit in 2019 and Travel+Leisure the best island.[41][42] Sri Lanka's top export destinations are the United States, United Kingdom and India. China, India and the UAE are the main import partners.[43]

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, lingering concerns over Sri Lanka's slowing growth, money printing and government debt has spilled over into a series of sovereign rating downgrades.[44][45] Import controls and import substitution have intensified after heightened monetary instability coming from debt monetization.[46][47][48][49] Sri Lanka has been named among the top 10 countries in the world in its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.[50] In 2021, the Sri Lankan Government officially declared the worst economic crisis in the country in 73 years.[51] Sri Lanka said most foreign debt repayments had been suspended from April 12, after two years of money printing to support tax cuts, ending an unblemished record of debt service.[52]

Economic history

Early history

Sri Lanka has a long history as a trading hub as a result of being located at the centre of east–west trade and irrigated agriculture in the hinterland, which is known from historical texts surviving within the island and from accounts of foreign travellers. The island has irrigation reservoirs called tanks built by ancient Kings starting after Indo-Aryan migration, many of which survive to this day.[53] They form part of an irrigation system interlinked with more modern constructions.[54]

Faxian (also Fa Hsien) a Chinese Monk who travelled to India and Sri Lanka around 400 AD, writes of existing legends at his time of merchants from other countries trading with native tribal peoples in the island before Indo-Aryan settlement. "The country which originally had no human inhabitants but was occupied by spirits and nagas (serpent worshipers) with which merchants of various countries carried on a trade," Faxian wrote in 'A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms'.[55] He writes of precious stones and pearl fisheries with a 30% tax by the king.

The monk had embarked "in a large merchant vessel" from India to arrive in the island.[55] To go back to China he "took passage in a large merchantman on board which were more than 200 men", ran into a storm where the merchants were forced to throw part of the cargo overboard and arrived at Java-dvipa (Indonesia), showing Sri Lanka had active coastal and long distance maritime trade links.[56]

Cosmas Indicopleustes (Indian Voyager), a merchant/monk from Alexandria of Egypt, who visited the Indian sub-continent in the 6th century, wrote in detail about Sri Lanka as a centre of commerce, referring to the island as Taprobane and Sieladiba.

"The island being, as it is, in a central position, is much frequented by ships from all parts of India and from Persia and Ethiopia, and it likewise sends out many of its own," he wrote in Christian Topography. "And from the remotest countries, I mean Tzinista and other trading places, it receives silk, aloes, cloves, sandalwood and other products, and these again are passed on to marts on this side, such as Male ... and to Calliana ... This same Sielediba then, placed as one may say, in the centre of the Indies and possessing the hyacinth receives ... and in turn exports to them, and is thus itself a great seat of commerce."[57]

Independence to 1977

Sri Lanka was ahead of many Asian nations and had economic and social indicators comparable to Japan when it gained independence from the British in 1948.

Sri Lanka's social indicators were considered "exceptionally high". Literacy was already 21.7% by the late 19th century. A Malaria eradication policy of 1946 had cut the death rate from 20 per thousand in 1946 to 14 by 1947. Life expectancy at birth of a Sri Lankan in 1948 at 54 years was just under Japan's 57.5 years. Sri Lanka's infant mortality rate in 1950 was 82 deaths per thousand live births, Malaysia 91 and Philippines 102.[58]

With its strategic location in the Indian Ocean Sri Lanka was expected to have a better chance than most other Asian neighbours to register a rapid economic take-off and had "appeared to be one of the most promising new nations." But the optimism in 1948 had dimmed by 1960, due to wrong economic policies and mismanagement.

East Asia was gradually overtaking Sri Lanka. In 1950 Sri Lanka's un-adjusted school enrolment ratio as a share of the 5-19 year age group was 54%, India 19%, Korea 43% and the Philippines 59%. But by 1979 Sri Lanka's school enrollment rate was 74%, but the Philippines had improved to 85% and Korea was 94%.[58]

Sri Lanka had inherited a stable macro-economy at independence.[59] A central bank was set up and Sri Lanka became a member of the IMF entering the Bretton Woods system of currency pegs on August 29, 1950.[60] By 1953 exchange controls were tightened with a new law.[61]

The economy was then progressively controlled and relaxed in response to foreign exchange crises as monetary and fiscal policies deteriorated. Controls and restrictions in 1961-64 were followed by partial liberalization in 1965–70. Controls were continued after a devaluation in the wake of 1967 Sterling Crisis. Controls were tightened from 1970 to 1977 alongside the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. "In sum it was a story of tightening partial relaxing, and again tightening the trade regime and associated areas to over a perceived foreign exchange crisis," writes economist Saman Kelegama in 'Development in Independent Sri Lanka what went wrong'. "In the early 1960s strategy for dealing with the foreign exchange crisis was the gradual isolation of the economy from external market forces. It was the beginning of a standard import-substitution industrial regime with all the controls and restrictions associated with such a regime. Expropriation and state intervention in economic activities was common."[59]

In 1960 Sri Lanka's (then Ceylon) per capita GDP was 152 dollars, Korea 153, Malaysia 280, Thailand 95, Indonesia 62, Philippines 254, Taiwan 149. But by 1978 Sri Lanka's per capita GDP was 226, Malaysia 588, Indonesia 370 and Taiwan 505.[58]

The 1970s also saw an uprising in the south from the JVP insurrection, and the roots of a civil war in the North and the East.

Post 1977 period

In 1977, Colombo abandoned statist economic policies and its import substitution industrialisation policy for market-oriented policies and export-oriented trade. Sri Lanka would after that be known to handle dynamic industries such as food processing, textiles and apparel, food and beverages, telecommunications, and insurance and banking. In the 1970s, the share of the middle class increased.[62]

Between 1977 and 1994 the country came under UNP rule in which under President J.R Jayawardana Sri Lanka began to shift away from a socialist orientation in 1977. Since then, the government has been deregulating, privatizing, and opening the economy to international competition. In 2001, Sri Lanka faced bankruptcy, with debt reaching 101% of GDP. The impending currency crisis was averted after the country reached a hasty ceasefire agreement with the LTTE and brokered substantial foreign loans. After 2004 the UPFA government has concentrated on the mass production of goods for domestic consumption such as rice, grain and other agricultural products.[63] however twenty-five years of civil war slowed economic growth,[citation needed] diversification and liberalisation, and the political group Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) uprisings, especially the second in the early 1980s, also caused extensive upheavals.[64]

Following the quelling of the JVP insurrection, increased privatization, economic reform, and the stress on export-oriented growth helped improve economic performance, increasing GDP growth to 7% in 1993. By 1996 plantation crops made up only 20% of exports (compared with 93% in 1970), while textiles and garments accounted for 63%. GDP grew at an annual average rate of 5.5% throughout the 1990s until a drought and a deteriorating security situation lowered growth to 3.8% in 1996.

The economy rebounded in 1997–98 with a growth of 6.4% and 4.7% – but slowed to 3.7% in 1999. For the next round of reforms, the central bank of Sri Lanka recommends that Colombo expand market mechanisms in nonplantation agriculture, dismantle the government's monopoly on wheat imports, and promote more competition in the financial sector. Economic growth has been uneven in the ensuing years as the economy faced a multitude of global and domestic economic and political challenges. Overall, average annual GDP growth was 5.2% over 1991–2000.

In 2001, however, GDP growth was negative 1.4% – the first contraction since independence. The economy was hit by a series of global and domestic economic problems and was affected by terrorist attacks in Sri Lanka and the United States. The crises also exposed the fundamental policy failures and structural imbalances in the economy and the need for reforms. The year ended in parliamentary elections in December, which saw the election of United National Party to Parliament, while Sri Lanka Freedom Party retained the presidency.

During the short-lived peace process from 2002 to 2004, the economy benefited from lower interest rates, a recovery in domestic demand, increased tourist arrivals, a revival of the stock exchange, and increased foreign direct investment (FDI). In 2002, the economy experienced a gradual recovery. During this period Sri Lanka has been able to reduce defense expenditures and begin to focus on getting its large, public sector debt under control. In 2002, economic growth reached 4%, aided by strong service sector growth. The agricultural sector of the economy staged a partial recovery. Total FDI inflows during 2002 were about $246 million[65]

The Mahinda Rajapakse government halted the privatization process and launched several new companies as well as re-nationalising previous state-owned enterprises, one of which the courts declared that privatization is null and void.[66] Some state-owned corporations became overstaffed and less efficient, making huge losses with series of frauds being uncovered in them and nepotism rising.[67] During this time, the EU revoked GSP plus preferential tariffs from Sri Lanka due to alleged human rights violations, which cost about US$500 million a year.[68][69]

The resumption of the civil war in 2005 led to a steep increase defense expenditures. The increased violence and lawlessness also prompted some donor countries to cut back on aid to the country.[70][71]

A sharp rise in world petroleum prices combined with the economic fallout from the civil war led to inflation that peaked at 20%.[citation needed]

Post-civil war period

Pre-2009, there was a continuing cloud over the economy with the civil war and fighting between the Government of Sri Lanka and the LTTE; however, the war ended with a resounding victory for the Sri Lankan Government on 19 May 2009 with the total elimination of the LTTE.[citation needed]

As the civil war ended in May 2009 the economy started to grow at a higher rate of 8.0% in the year 2010 and reached 9.1% in 2012, mostly due to the boom in non-tradable sectors; however, the boom did not last and the GDP growth for 2013 fell to 3.4% in 2013, and only slightly recovered to 4.5% in 2014.[72][73][74][75]

According to government policies and economic reforms stated by Prime Minister and Minister of National Policy and Economic Affairs Ranil Wickremesinghe, Sri Lanka plans to create Western Region Megapolis a Megapolis in the western province to promote economic growth. The creation of several business and technology development areas island-wide specialised in various sectors, as well as tourism zones, are also being planned.[76][77][78][79] In the mid to late 2010s, Sri Lanka faced a danger of falling into economic malaise, with increasing debt levels and a political crisis which saw the country's debt rating being dropped.[80] In 2016 the government succeeded in lifting an EU ban on Sri Lankan fish products which resulted in fish exports to EU rising by 200% and in 2017 improving human rights conditions resulted in the European Commission proposing to restore GSP plus facility to Sri Lanka.[77][78][81][82] Sri Lanka's tax revenues per GDP also increased from 10% in 2014, which was the lowest in nearly two decades to 12.3% in 2015.[83] Despite reforms, Sri Lanka was listed among countries with the highest risk for investors by Bloomberg.[84] Growth also further slowed to 3.3% in 2018 and 2.3% in 2019.[85] The rupee fell from 131 to the US dollar to 182 from 2015 to 2019, inflating foreign debt and slowing domestic consumption ending a period of relative stability.[86] China became a top creditor to Sri Lanka over the last decade, overtaking Japan and the World Bank.[87]

The main economic sectors of the country are tourism, tea export, apparel, textile, rice production and other agricultural products. In addition to these economic sectors, overseas employment contributes highly in foreign exchange.[88]

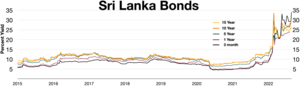

Inverted yield curve in the first half of 2022

In early March 2022 the Sri Lankan Rupee began losing value quickly

As of the early 2020s, the debt-laden country is undergoing an economic crisis where locals are experiencing months of shortages of food, fuel and electricity. Inflation has peaked to 57% according to official data.[62] In June 2022, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe declared in parliament the collapse of the Sri Lankan economy, leaving it unable to pay for essentials.[89]

Macroeconomic trends

The chart below summarizes the trend of Sri Lanka's gross domestic product at market prices.[90] by the International Monetary Fund with figures in millions of Sri Lankan Rupees.

| Year | Gross Domestic Product | US Dollar Exchange |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 66,167 | 16.53 Sri Lankan Rupees |

| 1985 | 162,375 | 27.20 Sri Lankan Rupees |

| 1990 | 321,784 | 40.06 Sri Lankan Rupees |

| 1995 | 667,772 | 51.25 Sri Lankan Rupees |

| 2000 | 1,257,637 | 77.00 Sri Lankan Rupees |

| 2005 | 2,363,669 | 100.52 Sri Lankan Rupees |

| 2016 | 6,718,000 | 145.00 Sri Lankan Rupees |

| 2020 | 14,601,600 | 189.00 Sri Lankan Rupees |

For purchasing power parity comparisons, the US Dollar is exchanged at 113.4 Sri Lankan Rupees only.

The following table shows the main economic indicators from 1980 to 2020.[91]

| Year | GDP (in Bil. US$ PPP) |

GDP (in Bil. US$ nominal) |

GDP per capita (in US$ PPP) |

GDP per capita in $ (Nominal) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation (in Percent) |

Government debt (Percentage of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 16.58 | 4.02 | 1,135 | 267 | 5.8% | 26.1% | 78% |

| 1985 | 27.43 | 5.97 | 1,772 | 369 | 5.0% | 1.5% | 95% |

| 1990 | 37.74 | 8.03 | 2,320 | 463 | 6.2% | 21.5% | 82% |

| 1995 | 56.28 | 13.03 | 3,257 | 714 | 6.1% | 7.7% | 80% |

| 2000 | 83.03 | 16.33 | 4,496 | 869 | 8.4% | 6.2% | 82% |

| 2005 | 112.59 | 24.41 | 5,739 | 1,248 | 6.2% | 11.0% | 79% |

| 2006 | 124.94 | 28.28 | 6,319 | 1,435 | 7.7% | 10.0% | 77% |

| 2007 | 136.99 | 32.35 | 6,874 | 1,630 | 6.8% | 15.8% | 74% |

| 2008 | 147.99 | 40.71 | 7,309 | 2,037 | 6.0% | 9.6% | 71% |

| 2009 | 154.39 | 42.07 | 7,540 | 2,090 | 3.5% | 3.4% | 75% |

| 2010 | 168.80 | 56.73 | 8,164 | 2,799 | 8.0% | 6.3% | 72% |

| 2011 | 186.76 | 65.29 | 8,949 | 3,200 | 8.4% | 6.7% | 71% |

| 2012 | 207.60 | 68.43 | 10,164 | 3,350 | 9.1% | 7.5% | 70% |

| 2013 | 218.11 | 74.32 | 10,599 | 3,610 | 3.4% | 6.9% | 72% |

| 2014 | 233.01 | 79.36 | 11,220 | 3,819 | 5.0% | 2.8% | 72% |

| 2015 | 247.37 | 80.60 | 11,798 | 3,843 | 5.0% | 2.2% | 78% |

| 2016 | 261.72 | 82.40 | 12,343 | 3,886 | 4.5% | 4.0% | 80% |

| 2017 | 274.72 | 87.42 | 12,811 | 4,076 | 3.1% | 6.5% | 79% |

| 2018 | 285.37 | 87.95 | 13,169 | 4,058 | 3.8% | 3.8% | 84% |