A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Melbourne Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

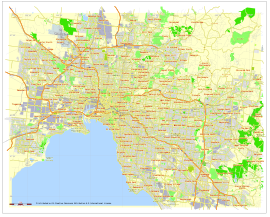

Map of Melbourne, Australia, printable and editable | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°48′51″S 144°57′47″E / 37.81417°S 144.96306°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 5,207,145 (2023)[1] (2nd) | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 521.079/km2 (1,349.59/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 30 August 1835 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 31 m (102 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 9,993 km2 (3,858.3 sq mi)(GCCSA)[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10) | ||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | AEDT (UTC+11) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | |||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | 31 municipalities across Greater Melbourne | ||||||||||||||

| County | Bourke, Evelyn, Grant, Mornington | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | 55 electoral districts and regions | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | 23 divisions | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Melbourne (/ˈmɛlbərn/ ⓘ MEL-bərn;[note 1] locally [ˈmælbən], Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: Narrm or Naarm[9][10]) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a 9,993 km2 (3,858 sq mi) metropolitan area also known as Greater Melbourne,[11] comprising an urban agglomeration of 31 local municipalities,[12] although the name is also used specifically for the local municipality of City of Melbourne based around its central business area.

The metropolis occupies much of the northern and eastern coastlines of Port Phillip Bay and spreads into the Mornington Peninsula, part of West Gippsland, as well as the hinterlands towards the Yarra Valley, the Dandenong Ranges, and the Macedon Ranges. Melbourne has a population over 5 million (19% of the population of Australia, as of the 2021 census), mostly residing to the east of the city centre, and its inhabitants are commonly referred to as "Melburnians".[note 2]

The area of Melbourne has been home to Aboriginal Victorians for over 40,000 years and serves as an important meeting place for local Kulin nation clans.[15][16] Of the five peoples of the Kulin nation, the traditional custodians of the land encompassing Melbourne are the Boonwurrung, Wathaurong and the Wurundjeri peoples. A short-lived penal settlement was built in 1803 at Port Phillip, then part of the British colony of New South Wales. However, it was not until 1835, with the arrival of free settlers from Van Diemen's Land (modern-day Tasmania), that Melbourne was founded.[15] It was incorporated as a Crown settlement in 1837, and named after William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne,[15] who was then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. In 1851, four years after Queen Victoria declared it a city, Melbourne became the capital of the new colony of Victoria.[17] During the 1850s Victorian gold rush, the city entered a lengthy boom period that, by the late 1880s, had transformed it into one of the world's largest and wealthiest metropolises.[18][19] After the federation of Australia in 1901, Melbourne served as the interim seat of government of the new nation until Canberra became the permanent capital in 1927.[20] Today, it is a leading financial centre in the Asia-Pacific region and ranked 32nd globally in the March 2022 Global Financial Centres Index.[21]

Melbourne is home of many of Australia's best-known landmarks, such as the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the National Gallery of Victoria and the World Heritage-listed Royal Exhibition Building. Noted for its cultural heritage, the city gave rise to Australian rules football, Australian impressionism and Australian cinema, and has more recently been recognised as a UNESCO City of Literature and a global centre for street art, live music and theatre. It hosts major annual international events, such as the Australian Grand Prix and the Australian Open, and also hosted the 1956 Summer Olympics. Melbourne consistently ranked as the world's most liveable city for much of the 2010s.[22]

Melbourne Airport, also known as the Tullamarine Airport, is the second-busiest airport in Australia, and the Port of Melbourne is the nation's busiest seaport.[23] Its main metropolitan rail terminus is Flinders Street station and its main regional rail and road coach terminus is Southern Cross station. It also has Australia's most extensive freeway network and the largest urban tram network in the world.[24]

History

Early history and foundation

Aboriginal Australians have lived in the Melbourne area for at least 40,000 years.[25] When European colonisers arrived in the 19th century, at least 20,000 Kulin people from three distinct language groups – the Wurundjeri, Bunurong and Wathaurong – resided in the area.[26][27] It was an important meeting place for the clans of the Kulin nation alliance and a vital source of food and water.[28][16] In June 2021, the boundaries between the land of two of the traditional owner groups, the Wurundjeri and Bunurong, were agreed after being drawn up by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council. The borderline runs across the city from west to east, with the CBD, Richmond and Hawthorn included in Wurundjeri land, and Albert Park, St Kilda and Caulfield on Bunurong land.[29] However, this change in boundaries is still disputed by people on both sides of the dispute including N'arweet Carolyn Briggs.[30] The name Narrm is commonly used by the broader Aboriginal community to refer to the city, stemming from the traditional name recorded for the area on which the Melbourne city centre is built.[31][9] The word is closely related to Narm-narm, being the Boonwurrung word for Port Phillip Bay.[32] Narrm means scrub in Eastern Kulin languages which reflects the Creation Story of how the Bay was filled by the creation of the Birrarung (Yarra River). Before this, the dry Melbourne region extended out into the Bay and the Bay was filled with teatree scrub where boordmul (emu) and marram (kangaroo) were hunted.[33][34]

The first British settlement in Victoria, then part of the penal colony of New South Wales, was established by Colonel David Collins in October 1803, at Sullivan Bay, near present-day Sorrento. The following year, due to a perceived lack of resources, these settlers relocated to Van Diemen's Land (present-day Tasmania) and founded the city of Hobart. It would be 30 years before another settlement was attempted.[35]

In May and June 1835, John Batman, a leading member of the Port Phillip Association in Van Diemen's Land, explored the Melbourne area, and later claimed to have negotiated a purchase of 2,400 km2 (600,000 acres) with eight Wurundjeri elders. However, the nature of the treaty has been heavily disputed, as none of the parties spoke the same language, and the elders likely perceived it as part of the gift exchanges which had taken place over the previous few days amounting to a tanderrum ceremony which allows temporary, not permanent, access to and use of the land.[36][28][16] Batman selected a site on the northern bank of the Yarra River, declaring that "this will be the place for a village" before returning to Van Diemen's Land.[37] In August 1835, another group of Vandemonian settlers arrived in the area and established a settlement at the site of the current Melbourne Immigration Museum. Batman and his group arrived the following month and the two groups ultimately agreed to share the settlement, initially known by the native name of Dootigala.[38][39]

Batman's Treaty with the Aboriginal elders was annulled by Richard Bourke, the Governor of New South Wales (who at the time governed all of eastern mainland Australia), with compensation paid to members of the association.[28] In 1836, Bourke declared the city the administrative capital of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales, and commissioned the first plan for its urban layout, the Hoddle Grid, in 1837.[40] Known briefly as Batmania,[41] the settlement was named Melbourne on 10 April 1837 by Governor Richard Bourke[42] after the British Prime Minister, William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, whose seat was Melbourne Hall in the market town of Melbourne, Derbyshire.[43] That year, the settlement's general post office officially opened with that name.[44]

Between 1836 and 1842, Victorian Aboriginal groups were largely dispossessed of their land by European settlers.[45] By January 1844, there were said to be 675 Aboriginal people resident in squalid camps in Melbourne.[46] The British Colonial Office appointed five Aboriginal Protectors for the Aboriginal people of Victoria, in 1839, however, their work was nullified by a land policy that favoured squatters who took possession of Aboriginal lands.[47] By 1845, fewer than 240 wealthy Europeans held all the pastoral licences then issued in Victoria and became a powerful political and economic force in Victoria for generations to come.[48]

Letters patent of Queen Victoria, issued on 25 June 1847, declared Melbourne a city.[17] On 1 July 1851, the Port Phillip District separated from New South Wales to become the Colony of Victoria, with Melbourne as its capital.[49]

Victorian gold rush

The discovery of gold in Victoria in mid-1851 sparked a gold rush, and Melbourne, the colony's major port, experienced rapid growth. Within months, the city's population had nearly doubled from 25,000 to 40,000 inhabitants.[50] Exponential growth ensued, and by 1865 Melbourne had overtaken Sydney as Australia's most populous city.[51]

An influx of intercolonial and international migrants, particularly from Europe and China, saw the establishment of slums, including Chinatown and a temporary "tent city" on the southern banks of the Yarra. In the aftermath of the 1854 Eureka Rebellion, mass public support for the plight of the miners resulted in major political changes to the colony, including improvements in working conditions across mining, agriculture, manufacturing and other local industries. At least twenty nationalities took part in the rebellion, giving some indication of immigration flows at the time.[52]

With the wealth brought in from the gold rush and the subsequent need for public buildings, a program of grand civic construction soon began. The 1850s and 1860s saw the commencement of Parliament House, the Treasury Building, the Old Melbourne Gaol, Victoria Barracks, the State Library, University of Melbourne, General Post Office, Customs House, the Melbourne Town Hall, St Patrick's cathedral, though many remained incomplete for decades, with some still not finished as of 2018[update].[citation needed]

The layout of the inner suburbs on a largely one-mile grid pattern, cut through by wide radial boulevards and parklands surrounding the central city, was largely established in the 1850s and 1860s. These areas rapidly filled with the ubiquitous terrace houses, as well as with detached houses and grand mansions, while some of the major roads developed as shopping streets. Melbourne quickly became a major finance centre, home to several banks, the Royal Mint, and (in 1861) Australia's first stock exchange.[53] In 1855, the Melbourne Cricket Club secured possession of its now famous ground, the MCG. Members of the Melbourne Football Club codified Australian football in 1859,[54] and in 1861, the first Melbourne Cup race was held. Melbourne acquired its first public monument, the Burke and Wills statue, in 1864.

With the gold rush largely over by 1860, Melbourne continued to grow on the back of continuing gold-mining, as the major port for exporting the agricultural products of Victoria (especially wool) and with a developing manufacturing sector protected by high tariffs. An extensive radial railway network spread into the countryside from the late 1850s. Construction started on further major public buildings in the 1860s and 1870s, such as the Supreme Court, Government House, and the Queen Victoria Market. The central city filled up with shops and offices, workshops, and warehouses. Large banks and hotels faced the main streets, with fine townhouses in the east end of Collins Street, contrasting with tiny cottages down laneways within the blocks. The Aboriginal population continued to decline, with an estimated 80% total decrease by 1863, due primarily to introduced diseases (particularly smallpox[26]), frontier violence and dispossession of their lands.

Land boom and bust

The 1880s saw extraordinary growth: consumer confidence, easy access to credit, and steep increases in land prices led to an enormous amount of construction. During this "land boom", Melbourne reputedly became the richest city in the world,[18] and the second-largest (after London) in the British Empire.[55]

The decade began with the Melbourne International Exhibition in 1880, held in the large purpose-built Exhibition Building. A telephone exchange was established that year, and the foundations of St Paul's were laid. In 1881, electric light was installed in the Eastern Market, and a generating station capable of supplying 2,000 incandescent lamps was in operation by 1882.[56] The Melbourne cable tramway system opened in 1885 and became one of the world's most extensive systems by 1890.

In 1885, visiting English journalist George Augustus Henry Sala coined the phrase "Marvellous Melbourne", which stuck long into the twentieth century and has come to refer to the opulence and energy of the 1880s,[57] during which time large commercial buildings, grand hotels, banks, coffee palaces, terrace housing and palatial mansions proliferated in the city.[58] The establishment of the Melbourne Hydraulic Power Company in 1886 led to the availability of high-pressure piped water, allowing for the installation of hydraulically powered elevators, which led to the construction of the first high-rise buildings in the city.[59][60] The period also saw the huge expansion of a significant radial rail-based transport network throughout the city and suburbs.[61]

Melbourne's land-boom peaked in 1888,[58] the year it hosted the Centennial Exhibition. The brash boosterism that had typified Melbourne during that time ended in the early 1890s. The bubble supporting the local finance and property industries burst, resulting in a severe economic depression.[58][62] Sixteen small "land banks" and building societies collapsed, and 133 limited companies went into liquidation. The Melbourne financial crisis was a contributing factor to the Australian economic depression of the 1890s and the Australian banking crisis of 1893. The effects of the depression on the city were profound, with virtually no significant construction until the late 1890s.[63][64]

Temporary capital of Australia and World War II

At the time of Australia's federation on 1 January 1901 Melbourne became the seat of government of the federated Commonwealth of Australia. The first federal parliament convened on 9 May 1901 in the Royal Exhibition Building, subsequently moving to the Victorian Parliament House, where it sat until it moved to Canberra in 1927. The Governor-General of Australia resided at Government House in Melbourne until 1930, and many major national institutions remained in Melbourne well into the twentieth century.[65][need quotation to verify]

During World War II the city hosted American military forces who were fighting the Empire of Japan, and the government requisitioned the Melbourne Cricket Ground for military use.[66]

Post-war period

In the immediate years after World War II, Melbourne expanded rapidly, its growth boosted by post-war immigration to Australia, primarily from Southern Europe and the Mediterranean.[67] While the "Paris End" of Collins Street began Melbourne's boutique shopping and open air cafe cultures,[68] the city centre was seen by many as stale—the dreary domain of office workers—something expressed by John Brack in his famous painting Collins St., 5 pm (1955).[69] Up until the 21st century, Melbourne was considered Australia's "industrial heartland".[70]

Height limits in the CBD were lifted in 1958, after the construction of ICI House, transforming the city's skyline with the introduction of skyscrapers. Suburban expansion then intensified, served by new indoor malls beginning with Chadstone Shopping Centre.[71] The post-war period also saw a major renewal of the CBD and St Kilda Road which significantly modernised the city.[72] New fire regulations and redevelopment saw most of the taller pre-war CBD buildings either demolished or partially retained through a policy of facadism. Many of the larger suburban mansions from the boom era were also either demolished or subdivided.

To counter the trend towards low-density suburban residential growth, the government began a series of controversial public housing projects in the inner city by the Housing Commission of Victoria, which resulted in the demolition of many neighbourhoods and a proliferation of high-rise towers.[73] In later years, with the rapid rise of motor vehicle ownership, the investment in freeway and highway developments greatly accelerated the outward suburban sprawl and declining inner-city population. The Bolte government sought to rapidly accelerate the modernisation of Melbourne. Major road projects including the remodelling of St Kilda Junction, the widening of Hoddle Street and then the extensive 1969 Melbourne Transportation Plan changed the face of the city into a car-dominated environment.[74]

Australia's financial and mining booms during 1969 and 1970 resulted in establishment of the headquarters of many major companies (BHP and Rio Tinto, among others) in the city. Nauru's then booming economy resulted in several ambitious investments in Melbourne, such as Nauru House.[75] Melbourne remained Australia's main business and financial centre until the late 1970s, when it began to lose this primacy to Sydney.[76]

Melbourne experienced an economic downturn between 1989 and 1992, following the collapse of several local financial institutions. In 1992, the newly elected Kennett government began a campaign to revive the economy with an aggressive development campaign of public works coupled with the promotion of the city as a tourist destination with a focus on major events and sports tourism.[77] During this period the Australian Grand Prix moved to Melbourne from Adelaide. Major projects included the construction of a new facility for the Melbourne Museum, Federation Square, the Melbourne Convention & Exhibition Centre, Crown Casino and the CityLink tollway. Other strategies included the privatisation of some of Melbourne's services, including power and public transport, and a reduction in funding to public services such as health, education and public transport infrastructure.[78]

Contemporary Melbourne

Since the mid-1990s, Melbourne has maintained significant population and employment growth. There has been substantial international investment in the city's industries and property market. Major inner-city urban renewal has occurred in areas such as Southbank, Port Melbourne, Melbourne Docklands and South Wharf. Melbourne sustained the highest population increase and economic growth rate of any Australian capital city from 2001 to 2004.[79]

From 2006, the growth of the city extended into "green wedges" and beyond the city's urban growth boundary. Predictions of the city's population reaching 5 million people pushed the state government to review the growth boundary in 2008 as part of its Melbourne @ Five Million strategy.[80] In 2009, Melbourne was less affected by the late-2000s financial crisis in comparison to other Australian cities. At this time, more new jobs were created in Melbourne than any other Australian city—almost as many as the next two fastest growing cities, Brisbane and Perth, combined,[81] and Melbourne's property market remained highly priced,[82] resulting in historically high property prices and widespread rent increases.[83]

Beginning in the 2010s the State Government of Victoria initiated a number of major infrastructure projects designed to reduce congestion in Melbourne and encourage economic growth, including the Metro Tunnel, the West Gate Tunnel, the Level Crossing Removal Project and the Suburban Rail Loop.[84][85] New urban renewal zones were initiated in inner-city areas like Fisherman's Bend and Arden, while suburban growth continued on the urban periphery in Melbourne's outer west and east in suburbs like Wyndham Vale and Cranbourne.[86] Middle suburbs like Box Hill became denser as a greater proportion of Melburnians began living in apartments.[87] A construction boom resulted in 34 new skyscrapers being built in the central business district between 2010 and 2020.[88] In 2020, Melbourne was classified as an Alpha city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[89]

Out of all major Australian cities, Melbourne was the worst affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and spent a long time under lockdown restrictions,[90] with Melbourne experiencing six lockdowns totalling 262 days.[91] While this contributed to a net outflow of migration causing a slight reduction in Melbourne's population over the course of 2020 to 2022, Melbourne is projected to be the fastest growing capital city in Australia from 2023–24 onwards, overtaking Sydney as the nation's largest city in 2029–30 at just over 5.9 million, exceeding 6 million people the following year.[92][93]

Geography

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2018) |

Melbourne is in the southeastern part of mainland Australia, within the state of Victoria.[94] Geologically, it is built on the confluence of Quaternary lava flows to the west, Silurian mudstones to the east, and Holocene sand accumulation to the southeast along Port Phillip. The southeastern suburbs are situated on the Selwyn fault, which transects Mount Martha and Cranbourne.[95] The western portion of the metropolitan area lies within the Victorian Volcanic Plain grasslands vegetation community,[96][97] and the southeast falls in the Gippsland Plains Grassy Woodland zone.[98]

Melbourne extends along the Yarra River towards the Yarra Valley and the Dandenong Ranges to the east. It extends northward through the undulating bushland valleys of the Yarra's tributaries—Moonee Ponds Creek (toward Tullamarine Airport), Merri Creek, Darebin Creek and Plenty River—to the outer suburban growth corridors of Craigieburn and Whittlesea.

The city reaches southeast through Dandenong to the growth corridor of Pakenham towards West Gippsland, and southward through the Dandenong Creek valley and the city of Frankston. In the west, it extends along the Maribyrnong River and its tributaries north towards Sunbury and the foothills of the Macedon Ranges, and along the flat volcanic plain country towards Melton in the west, Werribee at the foothills of the You Yangs granite ridge southwest of the CBD. The Little River, and the township of the same name, marks the border between Melbourne and neighbouring Geelong city.

Melbourne's major bayside beaches are in the various suburbs along the shores of Port Phillip Bay, in areas like Port Melbourne, Albert Park, St Kilda, Elwood, Brighton, Sandringham, Mentone, Frankston, Altona, Williamstown and Werribee South. The nearest surf beaches are 85 km (53 mi) south of the Melbourne CBD in the back-beaches of Rye, Sorrento and Portsea.[99][100]

Climate

Melbourne has a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb) with warm summers and cool winters.[101][102] Melbourne is well known for its changeable weather conditions, mainly due to it being located on the boundary of hot inland areas and the cool southern ocean. This temperature differential is most pronounced in the spring and summer months and can cause strong cold fronts to form. These cold fronts can be responsible for varied forms of severe weather from gales to thunderstorms and hail, large temperature drops and heavy rain. Winters, while exceptionally dry by south central Victorian standards, are nonetheless drizzly and overcast. The lack of winter rainfall is owed to Melbourne's rain shadowed location between the Otway and Macedon Ranges, which block much of the rainfall arriving from the north and west.

Port Phillip is often warmer than the surrounding oceans and/or the land mass, particularly in spring and autumn; this can set up a "bay effect", similar to the "lake effect" seen in colder climates, where showers are intensified leeward of the bay. Relatively narrow streams of heavy showers can often affect the same places (usually the eastern suburbs) for an extended period, while the rest of Melbourne and surrounds stays dry. Overall, the area around Melbourne is, owing to its rain shadow, nonetheless significantly drier than average for southern Victoria.[103] Within the city and surrounds, rainfall varies widely, from around 425 mm (17 in) at Little River to 1,250 mm (49 in) on the eastern fringe at Gembrook. Melbourne receives 48.6 clear days annually. Dewpoint temperatures in the summer range from 9.5 to 11.7 °C (49.1 to 53.1 °F).[104]

Melbourne is also prone to isolated convective showers forming when a cold pool crosses the state, especially if there is considerable daytime heating. These showers are often heavy and can include hail, squalls, and significant drops in temperature, but they often pass through very quickly with a rapid clearing trend to sunny and relatively calm weather and the temperature rising back to what it was before the shower. This can occur in the space of minutes and can be repeated many times a day, giving Melbourne a reputation for having "four seasons in one day",[104] a phrase that is part of local popular culture.[105] The lowest temperature on record is −2.8 °C (27.0 °F), on 21 July 1869.[106] The highest temperature recorded in Melbourne city was 46.4 °C (115.5 °F), on 7 February 2009.[106] While snow is occasionally seen at higher elevations in the outskirts of the city, and dustings were observed in 2020, it has not been recorded in the Central Business District since 1986.[107]

The average temperature of the sea ranges from 14.6 °C (58.3 °F) in September to 18.8 °C (65.8 °F) in February;[108] at Port Melbourne, the average sea temperature range is the same.[109]

| Climate data for Melbourne Airport (1991–2020 averages, 1970–2022 extremes) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 46.0 (114.8) |

46.8 (116.2) |

40.8 (105.4) |

34.5 (94.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

36.0 (96.8) |

41.6 (106.9) |

44.6 (112.3) |

46.8 (116.2) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 40.4 (104.7) |

38.2 (100.8) |

34.7 (94.5) |

28.8 (83.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.3 (93.7) |

37.6 (99.7) |

41.3 (106.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.2 (68.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.6 (69.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

10.2 (50.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.2 (57.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

6.4 (43.5) |

5.8 (42.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

8.7 (47.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

4.4 (39.9) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.3 (34.3) |

0.9 (33.6) |

1.1 (34.0) |

1.8 (35.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.9 (40.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

1.2 (34.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.9 (33.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39.3 (1.55) |

41.4 (1.63) |

37.5 (1.48) |

42.1 (1.66) |

34.3 (1.35) |

41.5 (1.63) |

32.8 (1.29) |

39.3 (1.55) |

46.1 (1.81) |

48.5 (1.91) |

60.1 (2.37) |

52.5 (2.07) |

515.5 (20.30) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8.3 | 7.5 | 8.4 | 9.9 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.8 | 13.9 | 12.5 | 10.8 | 9.9 | 135.0 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 44 | 45 | 46 | 50 | 59 | 65 | 63 | 57 | 53 | 49 | 47 | 45 | 52 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 272.8 | 231.7 | 226.3 | 183.0 | 142.6 | 120.0 | 136.4 | 167.4

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Melbourne,_Australia Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk | |||||