A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Golden Horde Ulug Ulus | |

|---|---|

| 1242–1502[1] | |

|

Flag during the reign of Öz Beg Khan as shown in Dulcert's 1339 map (other sources claim that the Golden Horde was named for the yellow banner of the khan)[2] | |

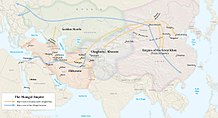

Territories of Golden Horde as of 1300 | |

| Status |

|

| Capital | |

| Common languages | |

| Religion |

|

| Government | Semi-elective monarchy, later hereditary monarchy |

| Khan | |

• 1226–1280 | Orda Khan (White Horde) |

• 1242–1255 | Batu Khan (Blue Horde) |

• 1379–1395 | Tokhtamysh |

• 1459–1465 | Mahmud bin Küchük (Great Horde) |

• 1481–1502 | Sheikh Ahmed |

| Legislature | Kurultai |

| Historical era | Late Middle Ages |

• Established | 1242 |

• Blue Horde and White Horde united | 1379 |

• Disintegrated into Great Horde | 1466 |

| 1480 | |

• Sack of Sarai by the Crimean Khanate | 1502[1] |

| Area | |

| 1310[5][6] | 6,000,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi) |

| Currency | Pul, som, dirham[7] |

| |

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus (lit. 'Great State' in Kipchak Turkic),[8] was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire.[9] With the division of the Mongol Empire after 1259, it became a functionally separate khanate. It is also known as the Kipchak Khanate or as the Ulus of Jochi,[a] and it replaced the earlier, less organized Cuman–Kipchak confederation.[10]

After the death of Batu Khan (the founder of the Golden Horde) in 1255, his dynasty flourished for a full century, until 1359, though the intrigues of Nogai instigated a partial civil war in the late 1290s. The Horde's military power peaked during the reign of Uzbeg Khan (1312–1341), who adopted Islam. The territory of the Golden Horde at its peak extended from Siberia and Central Asia to parts of Eastern Europe from the Urals to the Danube in the west, and from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea in the south, while bordering the Caucasus Mountains and the territories of the Mongol dynasty known as the Ilkhanate.[10]

The khanate experienced violent internal political disorder known as the Great Troubles (1359–1381), before it briefly reunited under Tokhtamysh (1381–1395). However, soon after the 1396 invasion of Timur, the founder of the Timurid Empire, the Golden Horde broke into smaller Tatar khanates which declined steadily in power. At the start of the 15th century, the Horde began to fall apart. By 1466, it was being referred to simply as the "Great Horde". Within its territories there emerged numerous predominantly Turkic khanates. These internal struggles allowed Moscow to formally rid itself of the "Tatar yoke" at the Great Stand on the Ugra River in 1480, which traditionally marks the end of Mongol rule over Russia.[11] The Crimean Khanate and the Kazakh Khanate, the last remnants of the Golden Horde, survived until 1783 and 1847 respectively, when they were conquered by the expanding Russian state.

Name

The name Golden Horde is a partial calque of Russian Золотая Орда (Zolotáya Ordá), itself supposedly a partial calque of Turkic Altan Orda. Золотая (Zolotáya) was translated to "Golden", while Орда (Ordá) was transliterated to "Horde".

The Turkic word orda means "palace", "camp" or "headquarters", in this case the headquarters of the khan, being the capital of the khanate, metonymically extended to the khanate itself. The English word "horde", in the sense of a large (and often threatening) group, emerged later, metaphorically extended from the reputation of the Mongol hordes.

The appellation "Golden" is said to have been inspired by the golden color of the tents the Mongols lived in during wartime, or an actual golden tent used by Batu Khan or by Uzbek Khan,[12] or to have been bestowed by the Slavic tributaries to describe the great wealth of the khan.

It was not until the 16th century that Russian chroniclers begin explicitly using the term to refer to this particular successor khanate of the Mongol Empire. The first known use of the term, in 1565, in a Russian chronicle called History of Kazan, applied it to the Ulus of Batu, centered on Sarai.[13][14] In contemporary Persian, Armenian and Muslim writings, and in the records of the 13th and early 14th centuries such as the Yuanshi and the Jami' al-tawarikh, the khanate was called the "Ulus of Jochi" ("realm of Jochi" in Mongolian), "Dasht-i-Qifchaq" (Qipchaq Steppe) or "Khanate of the Qipchaq" and "Comania" (Cumania).[15][16]

The eastern or left wing (or "left hand" in official Mongolian-sponsored Persian sources) was referred to as the Blue Horde in Russian chronicles and as the White Horde in Timurid sources (e.g. Zafar-Nameh). Western scholars have tended to follow the Timurid sources' nomenclature and call the left wing the White Horde. But Ötemish Hajji (fl. 1550), a historian of Khwarezm, called the left wing the Blue Horde, and since he was familiar with the oral traditions of the khanate empire, it seems likely that the Russian chroniclers were correct, and that the khanate itself called its left wing the Blue Horde.[17] The khanate apparently used the term White Horde to refer to its right wing, which was situated in Batu's home base in Sarai and controlled the ulus. The designations Golden Horde, Blue Horde, and White Horde have not been encountered in the sources of the Mongol period.[18]

Mongol origins (1225–1241)

At his death in 1227, Genghis Khan divided the Mongol Empire amongst his four sons as appanages, but the Empire remained united under the supreme khan. Jochi was the eldest, but he died six months before Genghis. The westernmost lands occupied by the Mongols, which included what is today southern Russia and Kazakhstan, were given to Jochi's eldest sons, Batu Khan, who eventually became ruler of the Blue Horde, and Orda Khan, who became the leader of the White Horde.[19][20] In 1235, Batu with the great general Subutai began an invasion westwards, first conquering the Bashkirs and then moving on to Volga Bulgaria in 1236. From there he conquered some of the southern steppes of present-day Ukraine in 1237, forcing many of the local Cumans to retreat westward. The Mongol campaign against the Kypchaks and Cumans had already started under Jochi and Subutai in 1216–1218 when the Merkits took shelter among them. By 1239 a large portion of Cumans were driven out of the Crimean peninsula, and it became one of the appanages of the Mongol Empire.[21] The remnants of the Crimean Cumans survived in the Crimean mountains, and they would, in time, mix with other groups in the Crimea (including Greeks, Goths, and Mongols) to form the Crimean Tatar population. Moving north, Batu began the Mongol invasion of Rus' and spent three years subjugating the principalities, whilst his cousins Möngke, Kadan, and Güyük moved southwards into Alania.

Using the migration of the Cumans as their casus belli, the Mongols continued west, raiding Poland and Hungary, which culminated in Mongol victories at the battles of Legnica and Mohi. In 1241, however, Ögedei Khan died in the Mongolian homeland. Batu turned back from his siege of Vienna but did not return to Mongolia, rather opting to stay at the Volga River. His brother Orda returned to take part in the succession. The Mongol armies would never again travel so far west. In 1242, after retreating through Hungary, destroying Pest in the process, and subjugating Bulgaria,[22] Batu established his capital at Sarai, commanding the lower stretch of the Volga River, on the site of the Khazar capital of Atil. Shortly before that, the younger brother of Batu and Orda, Shiban, was given his own enormous ulus east of the Ural Mountains along the Ob and Irtysh Rivers.

While the Mongolian language was undoubtedly in general use at the court of Batu, few Mongol texts written in the territory of the Golden Horde have survived, perhaps because of the prevalent general illiteracy. According to Grigor'ev, yarliq, or decrees of the Khans, were written in Mongol, then translated into the Cuman language. The existence of Arabic-Mongol and Persian-Mongol dictionaries dating from the middle of the 14th century and prepared for the use of the Egyptian Mamluk Sultanate suggests that there was a practical need for such works in the chancelleries handling correspondence with the Golden Horde. It is thus reasonable to conclude that letters received by the Mamluks – if not also written by them – must have been in Mongol.[22]

Golden Age

Batu Khan (1242–1256)

When the Great Khatun Töregene invited Batu to elect the next Emperor of the Mongol Empire in 1242, he declined to attend the kurultai and instead stayed at the Volga River. Although Batu excused himself by saying he was suffering from old age and illness, it seems that he did not support the election of Güyük Khan. Güyük and Büri, a grandson of Chagatai Khan, had quarreled violently with Batu at a victory banquet during the Mongol occupation of Eastern Europe. He sent his brothers to the kurultai, and the new Khagan of the Mongols was elected in 1246.

All the senior princes of Rus', including Yaroslav II of Vladimir, Daniel of Galicia, and Sviatoslav III of Vladimir, acknowledged Batu's supremacy. Originally Batu ordered Daniel to turn the administration of Galicia over to the Mongols, but Daniel personally visited Batu in 1245 and pledged allegiance to him. After returning from his trip, Daniel was visibly influenced by the Mongols, and equipped his army in the Mongol fashion, his horsemen with Mongol-style cuirasses, and their mounts armoured with shoulder, chest, and head pieces.[23] Michael of Chernigov, who had killed a Mongol envoy in 1240, refused to show obeisance and was executed in 1246.[24]

When Güyük called Batu to pay him homage several times, Batu sent Yaroslav II, Andrey II of Vladimir and Alexander Nevsky to Karakorum in Mongolia in 1247. Yaroslav II never returned and died in Mongolia. He was probably poisoned by Töregene Khatun, who probably did it to spite Batu and even her own son Güyük, because he did not approve of her regency.[25] Güyük appointed Andrey as the grand prince of Vladimir and Alexander was given the princely title of Kiev. However, when they returned, Andrey went to Vladimir while Alexander went to Novgorod instead. A bishop by the name of Cyril went to Kiev and found it so devastated that he abandoned the place and went further east instead.[26][27]

In 1248, Güyük demanded Batu come east to meet him, a move that some contemporaries regarded as a pretext for Batu's arrest. In compliance with the order, Batu approached, bringing a large army. When Güyük moved westwards, Tolui's widow and a sister of Batu's stepmother Sorghaghtani warned Batu that the Jochids might be his target. Güyük died on the way, in what is now Xinjiang, at about the age of 42. Although some modern historians believe that he died of natural causes because of deteriorating health,[28] he may have succumbed to the combined effects of alcoholism and gout, or he may have been poisoned. William of Rubruck and a Muslim chronicler state that Batu killed the imperial envoy, and one of his brothers murdered the Great Khan Güyük, but these claims are not completely corroborated by other major sources. Güyük's widow Oghul Qaimish took over as regent, but she was unable to keep the succession within her branch of the family.

With the assistance of Batu, Möngke succeeded as Great Khan in 1251. Utilizing the discovery of a plot designed to remove him, Möngke as the new Great Khan began a purge of his opponents. Estimates of the deaths of aristocrats, officials, and Mongol commanders range from 77 to 300. Batu became the most influential person in the Mongol Empire as his friendship with Möngke ensured the unity of the realm. Batu, Möngke, and other princely lines shared rule over the area from Afghanistan to Turkey. Batu allowed Möngke's census-takers to operate freely in his realm. Local censuses took place in the 1240s, including the areas of Russia and Turkey. In 1251–1259, Möngke conducted the first empire-wide census of the Mongol Empire; while North China was completed in 1252, Novgorod in the far northwest was not counted until winter of 1258–1259.[29] There was an uprising in Novgorod against the Mongol census, but Alexander Nevsky forced the city to submit to the census and taxation.[30]

With the new powers afforded to Batu by Möngke, he now had direct control over the princes of Rus'. However, Andrey II refused to submit to Batu. Batu sent a punitive expedition under Nevruy, who defeated Andrey and forced him to flee to Novgorod, then Pskov, and finally to Sweden. The Mongols overran Vladimir and harshly punished the principality. The Livonian Knights stopped their advance to Novgorod and Pskov. Thanks to his friendship with Sartaq Khan, Batu's son, who was a Christian, Alexander was installed as the grand prince of Vladimir by Batu in 1252.[31]

Berke (1258–1266)

After Batu died in 1256, his son Sartaq Khan was appointed by Möngke Khan. As soon as he returned from the court of the Great Khan in Mongolia, Sartaq died. The infant Ulaghchi succeeded him under the regency of Boragchin Khatun. The khatun summoned all the princes of Rus' to Sarai to renew their patents. In 1256, Andrey traveled to Sarai to ask for pardon. He was once again reappointed as the grand prince of Vladimir.[32]

Ulaghchi died soon after and Batu Khan's younger brother Berke, who had been converted to Islam, was enthroned as khan of the Golden Horde in 1258.[33]

In 1256, Daniel of Galicia openly defied the Mongols and ousted their troops in northern Podolia. In 1257, he repelled Mongol assaults led by the prince Kuremsa on Ponyzia and Volhynia and dispatched an expedition with the aim of taking Kiev. Despite initial successes, in 1259 a Mongol force under Boroldai entered Galicia and Volhynia and offered an ultimatum: Daniel was to destroy his fortifications or Boroldai would assault the towns. Daniel complied and pulled down the city walls. In 1259 Berke launched savage attacks on Lithuania and Poland, and demanded the submission of Béla IV, the Hungarian monarch, and the French King Louis IX in 1259 and 1260.[34] His assault on Prussia in 1259–1260 inflicted heavy losses on the Teutonic Order.[35] The Lithuanians were probably tributary in the 1260s, when reports reached the Curia that they were in league with the Mongols.[36]

In 1261, Berke approved the establishment of a church in Sarai.[37]