A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam in Iran |

|---|

|

| History of Islam in Iran |

| Scholars |

| Sects |

| Culture |

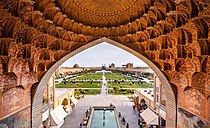

| Architecture |

| Organizations |

|

|

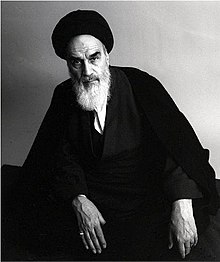

Traditionally, the thought and practice of Islamic fundamentalism and Islamism in the nation of Iran has referred to various forms of Shi'i Islamic religious revivalism[note 1] that seek a return to the original texts and the inspiration of the original believers of Islam. Issues of importance to the movement include the elimination of foreign, non-Islamic ideas and practices from Iran's society, economy and political system.[3][4] It is often contrasted with other strains of Islamic thought, such as traditionalism, quietism and modernism.[5] In Iran, Islamic fundamentalism and Islamism is primarily associated with the thought and practice of the leader of the Islamic Revolution and founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini ("Khomeinism"), but may also involve figures such as Fazlullah Nouri, Navvab Safavi, and successors of Khomeini.

In the 21st century, "fundamentalist" in the Islamic Republic of Iran generally refers to the political faction known as the "Principlists", (also spelled principlist) or Osoulgarayan[6]—as in acting politically based on principles of the Islamic Revolution[7][8][9]—which is an umbrella term for a variety of conservative circles and parties that (as of 2023) dominates politics in the country. (The Supreme Leader and the president are principalists, and principalists have control of the Assembly of Experts, the Guardian Council, the Expediency Discernment Council, and the Judiciary.)[10] The term contrasts with "reformist" or Eslaah-Talabaan, who seek religious and constitutional reforms.

Definitions and terminology

Some of the beliefs attributed to Islamic fundamentalists are that the primary sources of Islam (the Quran, Hadith, and Sunnah), should be interpreted in a literal and originalist way; that corrupting non-Islamic influences should be eliminated from every part of a Muslims' life; and that the societies, economies, and governance of Muslim-majority countries should return to the fundamentals of Islam, which make up a complete system including the Islamic state.[11][12][13] (The term fundamentalism has also been criticized as coming from Christianity and not truly appropriate for Islam.)[note 2]

Academics have made a variety of distinctions between Fundamentalism, Islamism (political Islam) and other terms in Iran and other Islamic societies. Yahya Sadowski, for example, distinguishes Islamic fundamentalism from Islamism, calling Islamism "neo-fundamentalism".[15] [16]

- A 2005 program on BBC Persian Service put Islamic movements among Iranians into three different categories: "traditionalists" (represented by Hossein Nasr, Yousef Sanei), "modernists" (represented by Abdolkarim Soroush), and "fundamentalists" (represented by Ali Khamenei, Mohammad Taghi Mesbah-Yazdi, and several Grand Ayatollahs including Mahdi Hadavi).[17]

- Javad Tabatabaei, Ronald Dworkin and a few other philosophers of law and politics have criticized the terminology of "conservatism", "fundamentalism" and "neo-fundamentalism" in the context of Iranian political philosophy, suggesting other classifications.[18][19][20][21]

- According to Bernard Lewis, when it comes to Political Islam:[22]

Even an appropriate vocabulary seemed to be lacking in western languages and writers on the subjects had recourse to such words as "revivalism", "fundamentalism" and "integrism." But most of these words have specifically Christian connotations, and their use to denote Islamic religious phenomena depends at best on a very loose analogy.

- A 2007 post from Radiozamaneh offered five categories for Iranian thinkers:[23]

- Anti-religious intellectuals

- Religious intellectuals

- Traditionists—who make up the majority of clerics, avoid modernity, neither accepting nor criticizing it.

- Traditionalists—who believe in eternal wisdom and are critics of humanism and modernity. Unlike Fundamentalists, Traditionalists believe in religious pluralism.

- Fundamentalists—Like Traditionalists and unlike Traditionists, Fundamentalists are against modernity and openly criticize it, Unlike both Traditionalists and Traditionists, fundamentalists believe that to revive the religion and put a stop to modernity they need to gain social and political power.[23]

History

Emergence

Fundamentalism in Iran as a reaction to Western technology, colonialism, and exploitation arose in the early 20th century,[24] and Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri and Navvab Safavi were among its pioneers figures.[25]

Iran was the first country in the post-World War II era in which political Islam became the rallying cry for a revolution, which was followed by formally adopting political Islam as its ruling ideology.[26] The grand alliance assembled by Ruhollah Khomeini that led to the 1979 revolution abandoned traditional clerical quietism, adopting diverse ideological interpretations of Islam. The first three Islamic discourses were Khomeinism, Ali Shariati's Islamic-left ideology, and Mehdi Bazargan's liberal-democratic Islam. The fourth discourse came from the socialist guerrilla groups of Islamic and secular variants, and the fifth was secular constitutionalism in socialist and nationalist forms.[27] By a few years after the triumph of the revolution, the only discourse left was Khomeinism.

Khomeini has been called a populist,[28] fundamentalist, Islamist, and a reformer[note 3] by various observers.

Pre-modern background

There are different theories as to when the ruling concept of the Ayatollah Khomeini and Islamic Republic of Iran—that Islamic jurists ought to govern until the return of the Imam Mahdi—first appeared. Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi[30] (and Ervand Abrahamian),[31] insists it was a revolutionary advance developed by Imam Khomeini. Other theories are that the idea is not at all new, but has been accepted by knowledgeable Shia faqih since medieval times, but kept from the general public by taqiya (precautionary dissimulation) (Ahmed Vaezi);[32] that it was "occasionally" interpreted during the reign of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1702 C.E.) (Hamid Algar),[33] argued by scholar Molla Ahmad Naraqi (1771–1829 C.E.) (Yasuyuki Matsunaga),[34] or by Morteza Ansari (~1781–1864 C.E.) (according to John Esposito).[35]

Developments that might be called steps easing the path to theocratic rule were the 16th century rise of the Safavid dynasty over modern day Iran which made Twelver Shi'ism the state religion and belief compulsory;[36][37] and in the late 18th century the triumph of the Usuli school of doctrine over the Akhbari. The latter change made the ulama "the primary educators" of society, dispensers most of the justice, overseers social welfare, and collectors of its funding (the zakat and khums religious taxes, managers of the "huge" waqf mortmains and other properties), and generally in control of activities that in modern states are left to the government.[38][39] The Usuli ulama were "frequently courted and even paid by rulers"[38][39] but, as the nineteenth century progressed, also came into conflict with them.

Era of colonialism and industrialization

End of nineteenth century marked the end of the Islamic middle ages. New technological advances in printing press, telegraph and railways, etc., along with political reforms brought major social changes and the institution of nation-state started to take shape.

Conditions under the Qajars

In the late 19th century, like most of the Muslim world, Iran suffered from foreign (European) intrusion and exploitation, military weakness, lack of cohesion, corruption. Under the Qajar dynasty (1789–1925), foreign (Western) mass-manufactured products, undercut the products of the bazaar, bankrupting seller,[41] cheap foreign wheat impoverish farmers.[41][42] The lack of a standing army and inferior military technology, meant loss of land and indemnity to Russia.[43] Lack of good governance meant "'large tracts of fertile land" went to waste.[44]

Perhaps worst of all the indignities Iran suffered from the superior militaries of European powers were "a series of commercial capitulations."[43] In 1872, Nasir al-Din Shah negotiated a concession granting a British citizen control over Persian roads, telegraphs, mills, factories, extraction of resources, and other public works in exchange for a fixed sum and 60% of net revenue. This concession was rolled back after bitter local opposition.[45][46] Other concessions to the British included giving the new Imperial Bank of Persia exclusive rights to issue banknotes, and opening up the Karun River to navigation.[47]

Concessions and the 1891–1892 Tobacco protest

The Tobacco protest of 1891–1892 was "the first mass nationwide popular movement in Iran",[47] and described as a "dress rehearsal for the ... Constitutional Revolution."[48]

In March 1890 Naser al-Din Shah granted a concession to an Englishman for a 50-year monopoly over the distribution and exportation of tobacco. Iranians cultivated a variety of tobacco "much prized in foreign markets" that was not grown elsewhere,[49] and the arrangement threatened the job security of a significant portion of the Iranian population—hundreds of thousands in agriculture and the bazaars.[50]

This led to unprecedented nationwide protest erupting first among the bazaari, then,[51] in December 1891, the most important religious authority in Iran, marja'-e taqlid Mirza Hasan Shirazi, issued a fatwa declaring the use of tobacco to be tantamount to war against the Hidden Imam. Bazaars shut down, Iranians stopped smoking tobacco,[52][53][47]

The protest demonstrated to the Iranians "for the first time" that it was possible to defeat the Shah and foreign interests. And the coalition of the tobacco boycott formed "a direct line ... culminating in the Constitutional Revolution" and arguably the Iranian Revolution as well, according to Historian Nikki Keddie.[54]

Whether the protest demonstrated that Iran could not be free of foreign exploitation with a corrupt, antiquated dictatorship; or whether it showed that it was Islamic clerics (and not secular thinkers/leaders) that had the moral integrity and popular influence to lead Iran against corrupt monarchs and the foreign exploitation they allowed, was disputed. Historian Ervand Abrahamian points out that Shirazi, "stressed that he was merely opposed to bad court advisers and that he would withdraw from politics once the hated agreement was canceled.[55]

1905–1911 Iranian Constitutional Revolution

As in other parts of the Muslim world, the question of how to strengthen the homeland against foreign encroachment and exploitation divided religious scholars and intellectuals. While many Iranians saw constitutional representative government as a necessary step, conservative clerics (like Khomeini and Fazlullah Nouri) saw it as a British plot to undermine sharia,[56] and part of foreign encroachment concerned Iranians were trying to protect Islam against.

The Constitutional Revolution began in 1905 with protest against a foreign director of customs (a Belgian) enforcing "with bureaucratic rigidity" the tariff collections to pay (in large part) for a loan to another foreign source (Russians) that financed the shah's (Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar) extravagant tour of Europe.

There were two different majlis (parliaments) endorsed by the leading clerics of Najaf – Akhund Khurasani, Mirza Husayn Tehrani and Shaykh Abdullah Mazandarani; in between there was a coup by the shah (Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar) against the constitutional government, a short civil war, and a deposing of that shah some months later.

It ended in December 1911 when deputies of the Second Majlis, suffering from "internal dissension, apathy of the masses, antagonisms from the upper class, and open enmity from Britain and Russia", were "roughly" expelled from the Majlis and threatened with death if they returned by "the shah's cabinet, backed by 12,000 Russian troops".[57]

The political base of the constitutionalist movement to control the power of the shah was an alliance of the ulama, liberal and radical intellectuals, and the bazaar. But the alliance was based on common enemies rather than common goals. The ulama sought "to extend their own power and to have Shi'i Islam more strictly enforced"; the liberals and radicals desired "greater political and social democracy and economic development"; and the bazaaris "to restrict favored foreign economic status and competition".[38]

Working to undermine the constitution and "exploit the divisions within the ranks of the reformers" were the shah Mohammad Ali, and court cleric Sheikh Fazlullah Nouri,[58] the leader of the anti-constitutionalists during the revolution.[59]

Khomeini, (though only a child at the time of the revolution), asserted later that the constitution of 1906 was the work of (Iranian) agents of imperialist Britain, conspiring against Islam who "were instructed by their masters to take advantage of the idea of constitutionalism in order to deceive the people and conceal the true nature of their political crimes".

"At the beginning of the constitutional movement, when people wanted to write laws and draw up a constitution, a copy of the Belgian legal code was borrowed from the Belgian embassy and a handful of individuals (whose names I do not wish to mention here) used it as the basis for the constitution they then wrote, supplementing its deficiencies with borrowings from the French and British legal codes. True, they added some of the ordinances of Islam in order to deceive the people, but the basis of the laws that were now thrust upon the people was alien and borrowed."[60]

On the other hand, Mirza Sayyed Mohammad Tabatabai, a cleric and leader of pro-constitutional faction, saw the constitutional fight against the shah as tied to patriotism and patriotism tied to Shi'i Islam:

"The Shiʿite state is confined to Persia, and their prestige and prosperity depended upon it. Why have you permitted the ruin of Persia and the utter humiliation of the Shiʿite state? ... You may reply that the mullahs did not allow . This is not credible. ... I can foresee that my country (waṭan), my stature and prestige, my service to Islam are about to fall into the hands of enemies and all my stature gone. As long as I breathe, therefore, I will strive for the preservation of this country, be it at the cost of my life."[61]

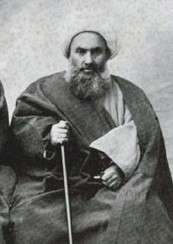

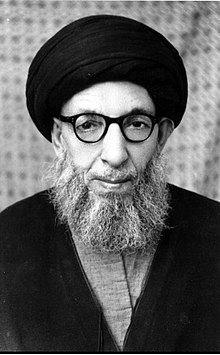

Fazlullah Nouri

If praise and official histories from the Islamic Republic of Iran can stand in for the heroes of Islamist/Fundamentalist Shi'ism, Sheikh Fazlullah Nouri (Persian: فضلالله نوری) is the Fundamentalist hero of the era. He was praised by Jalal Al-e-Ahmad the author of Gharbzadegi, and by Khomeini as an "heroic figure", and some believe his own objections to constitutionalism and a secular government were influenced by Nuri's objections to the 1907 constitution.[62][63][64] He was called the "Islamic movement's first martyr in contemporary Iran",[65] and honored to have an expressway named after him and postage stamps issued for him (the only figure of the Constitutional Revolution to be so honored).[65]

Nouri declared the new constitution contrary to sharia law. Like Islamists decades later,[66] preached the idea of sharia as a complete code of social life. In his newspaper Ruznamih-i-Shaikh Fazlullah, and published leaflets[67][68] to spread anti-constitutional propaganda;[67] and proclaim sentiments such as

Shari'a covers all regulations of government, and specifies all obligations and duties, so the needs of the people of Iran in matters of law are limited to the business of government, which, by reason of universal accidents, has become separated from Shari'a. ... Now the people have thrown out the law of the Prophet and have set up their own law instead.[69]

He led direct action against his opponents, such as an around-the-clock sit-in in the Shah Abdul Azim shrine by a large group of followers, from June 21, 1907 until September 16, 1907; recruiting mercenaries to harass the supporters of democracy, and leading a mob towards Tupkhanih Square December 22, 1907 to attack merchants and loot stores.[70]

But the sincerity of his religious beliefs has been questioned. Nouri was a wealthy, well-connected court official responsible for conducting marriages and contracts. Before opposing the idea of democratic reform he had been one of the leaders of the constitutional movement,[71] but reversed his political stance after the coronation of Muhammad Ali Shah Qajar, who unlike his father Mozaffar al-Din Shah, opposed constitutional monarchy. He took money and gave support to foreign (Russian) interests in Iran,[72] while warning Iranians of the spread of foreign ideas.[68]

Furthermore, Nouri was an "Islamic traditionalist"[73] or Fundamentalist rather than an Islamist. He opposed the Constitutionalists concept of limiting the powers of the monarchy, but not because he wanted monarchy abolished (like Khomeini and his followers) but because "obedience to the monarchy was a divine obligation".[72] Monarchy was an Islamic institution and the monarch was accountable to no one other than God and any attempt to call him to account was apostasy from Islam, a capital crime.

Also, unlike later Islamists, he preached against modern learning. Democracy was un-Islamic because it would lead to the "teaching of chemistry, physics and foreign languages", and result in spread of atheism;[74][68][75][76] female education because girls' schools were "brothels".[77] Other liberal ideas he opposed included allocation of funds for modern industry, freedom of press, and equal rights for non-Muslims.[citation needed]

Fazlullah Nouri was hanged by the constitutional revolutionaries on 31 July 1909 as a traitor, for playing pivotal role in coup d'état of Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar and for "the murder of leading constitutionalists"[72] by virtue of his denouncing them as "atheists, heretics, apostates, and secret Babis"—charges he knew would incite pious Muslims to violence.[72] The Shah had fled to Russia.

Religious supporters of the constitution

There was no shortage of Islamic scholars in support of the constitution. Acting as a legitimising force for the constitution[78] were three of the highest level clerics (marja') at the time—Akhund Khurasani, Mirza Husayn Tehrani and Shaykh Abdullah Mazandarani—who defended constitutional monarchy in the period of occultation by invoking the Quranic command of 'enjoining good and forbidding wrong'.[79] In doing so they linked opposition to the constitutional movement to 'a war against the Imam of the Age'[80] (a very severe condemnation in Shi'i Islam), and when parliament came under attack from Nuri issued fatawa forbidding his involvement in politics (December 30, 1907),[81] and then calling for his expulsion (1908).[82] In supporting the constitution, the three marja' established a model of religious secularity in government in the absence of Imam, that still prevails in (some) Shi'i seminaries.[79]

Nouri called on Shi'a to ignore the higher ranking of the marja' (the basis of Usuli Shi'ism) and their fatawa; he insisted that Shi'a were all "witnesses" that the marja' were obviously wrong in supporting the parliament.[83] Another cleric, Mirza Ali Aqa Tabrizi, defended the marja' ("the sources of emulation") and their "clear fatwas that uphold the necessity of the Constitution".[84]

- Akhund aka Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, Muhammad Hossein Naini, Shaykh Isma'il Mahallati

Some of the religious arguments offered for the constitution were that rather than having superior status that gave them the right to rule over ordinary people, the role of scholars/jurists was to act as "warning voices in society" and criticize the officials who were not carrying out their responsibilities properly.[85] and to provide religious guidance in personal affairs of believers.[86]

Until the infallible Imam returned to establish an Islamic system of governance with himself governing,[87] "human experience and careful reflection" indicated that democracy brought a set of "limitations and conditions" on the head of state and government officials keeping them within "boundaries that the laws and religion of every nation determines", reducing the tyranny of state", and preventing the corruption of power.[88] All this meant it was "obligatory to give precedence" to this "lesser evil" in governance.[89][87]

Muhammad Hossein Naini, a close associate and student of Behbahani, agreed that in the absence of Imam Mahdi, all governments are doomed to be imperfect and unjust, and therefore people had to prefer the bad (democracy) over the worse (absolutism). He opposed both "tyrannical Ulema" and radical majoritarianism, supporting features of liberal democracy, such as equal rights, freedom of speech, separation of powers.[90][91]

Another student of Akhund who too raised to the rank of Marja, Shaykh Isma'il Mahallati, wrote a treatise "al-Liali al-Marbuta fi Wajub al-Mashruta" (Persian: اللئالی المربوطه فی وجوب المشروطه).[87] during the occultation of the twelfth Imam, the governments can either be imperfectly just or oppressive. Limiting the sovereign's power through a constitution means limiting tyranny. Since it was the duty of the believer to fight injustice, they ought to work to strengthen the democratic process—reforming the economic system, modernizing the military, establishing an educational system.[86] At the same time, constitutional government was the option of both "Muslims or unbelievers".[86]

Reza Shah and the Pahlavi dynasty

While the Constitutional Revolution did not succeed, the secular, modernizing authoritarianism of the two Pahlavi shahs had more success, ruling from Reza Shah's seizure of power in 1921, to his son's overthrow in 1979, and can be said to have combatting Iran's backwardness. Reza Shah, leader of the Iranian Cossack Brigade before his coup, was a secular, nationalist dictator in the vein of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk of Turkey.[92][93] Under his rule Iran was militarily united, a 100,000-man standing army created, uniform Persian culture emphasized, and ambitious development projects undertaken: 1300 km railway linking the Persian Gulf with the Caspian Sea was built, a university, and free, compulsory primary education for both boys and girls was established while private religious schools were shut down.

- While his modernization efforts were significant, he was the bete noire of the clergy and pious Iranians,[94] (not least of all Ruhollah Khomeini). His government required all non-clerical men to wear Western clothes,[95] encouraged women to abandon hijab.[96] He expropriated land and real estate from shrines at Mashhad and Qom, to help finance secular education, "build a modern hospital, improve the water supply of the city, and underwrite industrial enterprises."[97] Khomeini focused his revolutionary campaign on the Pahlavi shah and all of his government's alleged shortcomings.

Fada'ian-e Islam

Fada'ian-e Islam (in English, literally "Self-Sacrificers of Islam") was a Shia fundamentalist group in Iran founded in 1946 and crushed in 1955. The Fada'ian "did not compare either in rank, number or popular base" with the mainstream conservative and progressive tendencies among the clergy, but killed a number of important people,[98] and at least one source (Sohrab Behdad) credits the group and Navvab Safavi with influence on the Islamic Revolution.[99] According to Encyclopaedia Iranica,

"there are important similarities between much of the Fedāʾīān's basic views and certain principles and actions of the Islamic Republic of Iran: the Fedāʾīān and Ayatollah Khomeini were in accord on issues such as the role of clerics , morality and ethics, Islamic justice , the place of the underclass , the rights of women and religious minorities , and attitudes toward foreign powers ."[100][101][102][103]

In addition, leading Islamic Republic figures such as Ali Khamenei, (the current Supreme Leader), and Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, (former president, former head of the Assembly of Experts, and former head of Expediency Discernment Council), have indicated what an "important formative impact of Nawwāb's charismatic appeal in their early careers and anti-government activities".[103]

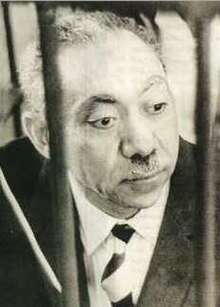

Sayyid Mojtaba Mir-Lohi (Persian: سيد مجتبی میرلوحی, c. 1924 – 18 January 1956), more commonly known as Navvab Safavi (Persian: نواب صفوی), emerged on political scene around 1945 when after only two years of study, he left the seminaries of Najaf[104] to found the Fada'iyan-e Islam, recruiting frustrated youth from suburbs of Tehran for acts of terror, proclaiming:

"We are alive and God, the revengeful, is alert. The blood of the destitute has long been dripping from the fingers of the selfish pleasure seekers, who are hiding, each with a different name and in a different colour, behind black curtains of oppression, thievery and crime. Once in a while the divine retribution puts them in their place, but the rest of them do not learn a lesson ..."[105]

In 1950, at 26 years of age, he presented his idea of an Islamic State in a treatise, Barnameh-ye Inqalabi-ye Fada'ian-i Islam.[106] Despite his hatred of interfering infidel foreign powers, his group attempted to kill prime minister Muhammad Musaddiq, and he congratulated the shah after the 1953 coup deposed Mosaddegh:[107]

"The country was saved by Islam and with the power of faith ... The Shah and prime minister and ministers have to be believers in and promoters of, shi'ism, and the laws that are in opposition to the divine laws of God ... must be nullified ... The intoxicants, the shameful exposure and carelessness of women, and sexually provocative music ... must be done away with and the superior teachings of Islam ... must replace them."[108]

He enjoyed a close enough association with the government to be able to attend a 1954 Islamic Conference in Jordan and traveled to Egypt and meet Sayyid Qutb.[109][110] He clashed with Shia Marja', Hossein Borujerdi, who rejected his ideas and questioned him about the robberies that his organization committed on gun point, Safavi replied:

"Our intention is to borrow from people. What we take is for establishing a government based on the model of Imam Ali's government. Our goal is sacred and prior to these tools. When we established an Aliid government-like state, then we give people their money back."[111][112]

Fada'ian-e Islam called for excommunication of Borujerdi and the defrocking of religious scholars who opposed their idea of Islam,[note 4] Navvab Safavi did not like Broujerdi's idea of Shia-Sunni rapprochement (Persian: تقریب), he advocated Shia-Sunni unification (Persian: وحدت) under Islamist agenda.[114] Fada'ian-e Islam carried out assassinations of Abdolhossein Hazhir, Haj Ali Razmara and Ahmad Kasravi. On 22 November 1955, after an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Hosein Ala', Navvab Safavi was arrested and sentenced to death on 25 December 1955 under terrorism charges, along with three other comrades.[109] The organization dispersed but after the death of Ayatullah Borujerdi, the Fada'ian-e Islam sympathizers found a new leader in Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini who appeared on political horizon through the June 1963 riots in Qom.[115] In 1965, prime minister Hassan Ali Mansur was assassinated by the group.[116]

Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 coup

Mohammad Mosaddeq was prime minister of Iran from 1951 to 1953 and led the nationalization of the British owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. Originally he and nationalization had mass support, with a core of "modern or politically literate middle-income or underprivileged segments of the urban population", but expanding to include "considerable support" from traditional sectors such as "guilds of restaurant owners, coffee and teahouse owners".[117] He was overthrown on 19 August 1953, aided by the United States[118] and the United Kingdom,[119][120][121][122] and "directly or indirectly helped" by sections of the military, landlords, conservative politicians, and "the bulk of the religious establishment".[123][124]

According to Fakhreddin Azimi, in the "modern Iranian historical and political consciousness" the 1953 coup "occupies an immensely significant place". The coup is "widely seen as a rupture, a watershed, a turning point when imperialist domination, overcoming a defiant challenge, reestablished itself, not only by restoring an enfeebled monarch but also by ensuring that the monarchy would assume an authoritarian and antidemocratic posture."[125]

Critics hold Mosaddegh and his supporters responsible for failing "to create an organization capable of mobilizing broad support for their movement"; refusing "to take the difficult steps necessary to settle the oil dispute; and not acting "forcefully against their various opponents, either before the coup or while it was underway."[126]

Mosaddeq was to his supporters struggling to "overcome orchestrated oppositional machinations through a consistently defiant, transparent, morally unassailable, principle-driven stance."[127] In Iranian domestic politics, the legacy of the coup was the firmly held belief by many Iranians "that the United States bore responsibility for Iran's return to dictatorship, a belief that helps to explain the heavily anti-American character of the revolution in 1978."[128]

Iranians felt exploited by the British, whose Anglo-Iranian Oil Company paid Iran royalties of $45 million for its oil in 1950, while paying the British government "taxes of $142 million on profits from that crude and its downstream products."[129] The Iranian operations of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (English owned but operating in Iran) was nationalized in 1951. Mosaddeq stated

"Our long years of negotiations with foreign countries... have yielded no results this far. With the oil revenues we could meet our entire budget and combat poverty, disease, and backwardness among our people. Another important consideration is that by the elimination of the power of the British company, we would also eliminate corruption and intrigue, by means of which the internal affairs of our country have been influenced. Once this tutelage has ceased, Iran will have achieved its economic and political independence. The Iranian state prefers to take over the production of petroleum itself. The company should do nothing else but return its property to the rightful owners. The nationalization law provide that 25% of the net profits on oil be set aside to meet all the legitimate claims of the company for compensation... It has been asserted abroad that Iran intends to expel the foreign oil experts from the country and then shut down oil installations. Not only is this allegation absurd; it is utter invention..."[130]

The AIOC management "immediately staged an economic boycott, with backing from the other major international oil companies, while the British government started an aggressive, semi-covert campaign to destabilize the Mosaddeq regime." The United States, the leader of the "Free world" bloc in the cold war was "ostensible neutral", but allied with the UK and worried about the influence of Iran's huge neighbor and leader of the communist bloc, the Soviet Union, the Truman administration "quietly abided by the boycott". As U.S. worries over Iran's political and economic deterioration increased,[131] and that the country's economy was "near collapse",[132] which would cause some combination of increased dependence on the Tudeh party leading to its eventual takeover,[133] and or "collapse followed by a communist takeover."[132]

Iran had difficulty finding trained non-British workers to run the industry and buyers to sell the oil to.[134] but the government was not near bankruptcy nor inflation unmanageable.[135]

Demographic changes

Iran was undergoing a fast societal change through urbanization. In 1925 Iran was a thinly populated country with a population of 12 millions, 21% living in urban centers and Tehran was a walled city of 200,000 inhabitants. Pahlavi dynasty started major projects of converting the capital into a metropolis.[136] Between 1956 and 1966, the rapid industrialization coupled with land reforms and improved health systems, building of dams and roads, released some three million peasants from countryside into the cities.[137] This resulted in rapid changes in their lives, decline of traditional feudal values, and industrialization, changing the socio-political atmosphere and created new questions.[138] By 1976, 47% of Iran's total population was concentrated in large cities. Between 42 and 50% of the population of Tehran lived on rent, 10% owned private car and 82.7% of all national companies were registered in the Capital.[139]

A less complimentary view of Nikki Keddie is that,

"especially after 1961, the crown encouraged the rapid growth of consumer-goods industries, pushed the acquisition of armaments even beyond what Iran's growing oil-rich budgets could stand, and instituted agrarian reforms that emphasized government control and investment in large, mechanized farms. Displaced peasants and tribespeople fled to the cities, where they formed a discontented sub-proletariat. People were torn from ancestral ways, the gap between the rich and the poor grew, corruption was rampant and well known, and the secret police, with its arbitrary arrests and use of torture, turned Iranians of all levels against the regime. And the presence and heavy influence of foreigners provided major, further aggravation.[38]

Rapid urbanization in Iran had created a modern educated, salaried middle class (as opposed to a traditional class of bazaari merchants). Among them were writers who started to criticize traditional interpretations of religion, and readers who agreed with them. In one of his first books, Kashf al-Asrar, Khomeini attacked these liberal critics and writers as a "brainless" treacherous "lot" whose teeth the believers must 'smash ... with their iron fist’ and heads they should 'trample upon ... with courageous strides’.[140] Furthermore

Government can only be legitimate when it accepts the rule of God and the rule of God means the implementation of the Sharia. All laws that are contrary to the Sharia must be dropped because only the law of God will stay valid and immutable in the face of changing times.[140]

Cold War literature

Following World War II, Western capitalist and other anti-Communist leaders were alarmed at how large, centralized and powerful the Eastern bloc of countries ruled by Communist parties (now including China), had become. As the peoples of Western colonial empires were given independence, the idea that poor, formerly colonialized countries naturally aligned with the Socialist Bloc, should follow socialist economic development models, and keep their distance from former colonizers, alarmed anti-communists still further. In the Muslim world this led to an effort to compete with Communist propaganda and the revolutionary enthusiasm of Marxist, anti-imperialist ideas by promoting works by the original Islamist thinkers, Sayyid Qutb and Abul A'la Al-Maududi (known to be deeply anti-Communist), through the Muslim World League with Saudi patronage, translating them into Farsi and other languages.[141]

Their books were translated into Persian/Farsi, and helped to shape the ideology of Shi'i Islamists.[113][142] Sayyid Qutb's works enjoyed remarkable popularity in Iran both before and after the revolution. Prominent figures such as current Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and his brother Muhammad Khamenei, Aḥmad Aram, Hadi Khosroshahi, etc. translated Qutb's works into Persian.[143][144] Hadi Khosroshahi was the first person to identify himself as Akhwani Shia.[145] Muhammad Khamenei is currently head of Sadra Islamic Philosophy Research Institute, and holds positions at Al-Zahra University and Allameh Tabataba'i University.[146] According to the National Library and Archives of Iran, 19 works of Sayyid Qutb and 17 works of his brother Muhammad Qutb were translated to Persian and widely circulated in the 1960s.[147] Reflecting on this import of ideas, Ali Khamenei said:

The newly emerged Islamic movement ... had a pressing need for codified ideological foundations ... Most writings on Islam at the time lacked any direct discussions of the ongoing struggles of the Muslim people ... Few individuals who fought in the fiercest skirmishes of that battlefield made up their minds to compensate for this deficiency ... This text was translated with this goal in mind.[148]

Concerned about the post-World War II geo-political expansion of Iran's powerful northern neighbor the Soviet Union, the Shah's regime in Iran tolerated this literature for its anti-Communist value,[149] but an indication that the Western Cold War strategy for the Muslim world was not working out as planned was indicated by the coining of the term "American Islam", in 1952, by one of the authors—Sayyid Qutb—that were being translated with Saudi and Western funding. The term was later adapted by Ayatullah Khomeini after the 1979 Islamist revolution,[150] who proclaimed:

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Islamic_fundamentalism_in_IranText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk