A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Glasgow (UK: /ˈɡlɑːzɡoʊ, ˈɡlæz-, ˈɡlɑːs-, ˈɡlæs-/ GLA(H)Z-goh, GLA(H)SS-)[8] is the most populous city in Scotland,[9] the third-most populous city in the United Kingdom,[10] and the 27th-most populous city in Europe.[11] In 2022, it had an estimated population as a defined locality of 632,350 and anchored an urban settlement of 1,028,220. Glasgow became a county in 1893, the city having previously been in the historic county of Lanarkshire, and later growing to also include settlements that were once part of Renfrewshire and Dunbartonshire. It now forms the Glasgow City Council area, one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, and is administered by Glasgow City Council.

The city is a member of the Core Cities Group, having the largest economy in Scotland and the third-highest GDP per capita of any city in the UK.[12][13] Glasgow's major cultural institutions enjoy international reputations including The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Burrell Collection, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Scottish Ballet and Scottish Opera. The city was the European Capital of Culture in 1990 and is notable for its architecture, culture, media, music scene, sports clubs and transport connections. It is the fifth-most visited city in the United Kingdom.[14] The city hosted the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) at its main events venue, the SEC Centre. Glasgow hosted the 2014 Commonwealth Games and the first European Championships in 2018, was one of the host cities for UEFA Euro 2020, and will be a host city of the UEFA Euro 2028. The city is also well known in the sporting world for football, particularly for the Old Firm rivalry.

Glasgow grew from a small rural settlement close to Glasgow Cathedral and descending to the River Clyde to become the largest seaport in Scotland, and tenth largest by tonnage in Britain. Expanding from the medieval bishopric and episcopal burgh (subsequently royal burgh), and the later establishment of the University of Glasgow in the 15th century, it became a major centre of the Scottish Enlightenment in the 18th century. From the 18th century onwards, the city also grew as one of Britain's main hubs of oceanic trade with North America and the West Indies; soon followed by the Orient, India, and China. With the onset of the Industrial Revolution, the population and economy of Glasgow and the surrounding region expanded rapidly to become one of the world's pre-eminent centres of chemicals, textiles and engineering; most notably in the shipbuilding and marine engineering industry, which produced many innovative and famous vessels. Glasgow was the "Second City of the British Empire" for much of the Victorian and Edwardian eras.[15][16][17][18]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Glasgow's population grew rapidly, reaching a peak of 1,127,825 people in 1938 (with a higher density and within a smaller territory than in subsequent decades).[19] The population was greatly reduced following comprehensive urban renewal projects in the 1960s which resulted in large-scale relocation of people to designated new towns, such as Cumbernauld, Livingston, East Kilbride and peripheral suburbs, followed by successive boundary changes. Over 1,000,000 people live in the Greater Glasgow contiguous urban area, while the wider Glasgow City Region is home to over 1,800,000 people, equating to around 33% of Scotland's population.[5] The city has one of the highest densities of any locality in Scotland at 4,023/km2.

Etymology

The name Glasgow is Brittonic in origin. The first element glas, meaning "grey-green, grey-blue" both in Brittonic, Scottish Gaelic and modern day Welsh and the second *cöü, "hollow" (cf. Welsh glas-cau),[20] giving a meaning of "green-hollow".[21] It is often said that the name means "dear green place" or that "dear green place" is a translation from Gaelic Glas Caomh.[22] "The dear green place" remains an affectionate way of referring to the city. The modern Gaelic is Glaschu and derived from the same roots as the Brittonic.

The settlement may have an earlier Brittonic name, Cathures; the modern name appears for the first time in the Gaelic period (1116), as Glasgu. It is also recorded that the King of Strathclyde, Rhydderch Hael, welcomed Saint Kentigern (also known as Saint Mungo), and procured his consecration as bishop about 540. For some thirteen years Kentigern laboured in the region, building his church at the Molendinar Burn where Glasgow Cathedral now stands, and making many converts. A large community developed around him and became known as Glasgu.

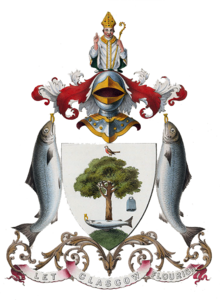

Heraldry

The coat of arms of the City of Glasgow was granted to the royal burgh by the Lord Lyon on 25 October 1866.[23] It incorporates a number of symbols and emblems associated with the life of Glasgow's patron saint, Mungo, which had been used on official seals prior to that date. The emblems represent miracles supposed to have been performed by Mungo[24] and are listed in the traditional rhyme:

- Here's the bird that never flew

- Here's the tree that never grew

- Here's the bell that never rang

- Here's the fish that never swam

St Mungo is also said to have preached a sermon containing the words Lord, Let Glasgow flourish by the preaching of the word and the praising of thy name. This was abbreviated to "Let Glasgow Flourish" and adopted as the city's motto.

In 1450, John Stewart, the first Lord Provost of Glasgow, left an endowment so that a "St Mungo's Bell" could be made and tolled throughout the city so that the citizens would pray for his soul. A new bell was purchased by the magistrates in 1641 and that bell is still on display in the People's Palace Museum, near Glasgow Green.

The supporters are two salmon bearing rings, and the crest is a half length figure of Saint Mungo. He wears a bishop's mitre and liturgical vestments and has his hand raised in "the act of benediction". The original 1866 grant placed the crest atop a helm, but this was removed in subsequent grants. The current version (1996) has a gold mural crown between the shield and the crest. This form of coronet, resembling an embattled city wall, was allowed to the four area councils with city status.

The arms were re-matriculated by the City of Glasgow District Council on 6 February 1975, and by the present area council on 25 March 1996. The only change made on each occasion was in the type of coronet over the arms.[25][26]

History

Origins and development

The area around Glasgow has hosted communities for millennia, with the River Clyde providing a natural location for fishing. The Romans later built outposts in the area and, to protect Roman Britannia from the Brittonic speaking (Celtic) Caledonians, constructed the Antonine Wall. Items from the wall, such as altars from Roman forts like Balmuildy, can be found at the Hunterian Museum today.

Glasgow itself was reputed to have been founded by the Christian missionary Saint Mungo in the 6th century. He established a church on the Molendinar Burn, where the present Glasgow Cathedral stands, and in the following years Glasgow became a religious centre. Glasgow grew over the following centuries. The Glasgow Fair reportedly began in 1190.[27] A bridge over the River Clyde was recorded from around 1285, where Victoria Bridge now stands. As the lowest bridging point on the Clyde it was an important crossing. The area around the bridge became known as Briggait. The founding of the University of Glasgow adjoining the cathedral in 1451 and elevation of the bishopric to become the Archdiocese of Glasgow in 1492 increased the town's religious and educational status and landed wealth. Its early trade was in agriculture, brewing and fishing, with cured salmon and herring being exported to Europe and the Mediterranean.[28] By the fifteenth century the urban area stretched from the area around the cathedral and university in the north down to the bridge and the banks of the Clyde in the south along High Street, Saltmarket and Bridgegate, crossing an east–west route at Glasgow Cross which became the commercial centre of the city.[29]

Following the European Protestant Reformation and with the encouragement of the Convention of Royal Burghs, the 14 incorporated trade crafts federated as the Trades House in 1605 to match the power and influence in the town council of the earlier Merchants' Guilds who established their Merchants House in the same year.[28] Glasgow was subsequently raised to the status of Royal Burgh in 1611.[30] Daniel Defoe visited the city in the early 18th century and famously opined in his book A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain, that Glasgow was "the cleanest and beautifullest, and best built city in Britain, London excepted". At that time the city's population was about 12,000, and the city was yet to undergo the massive expansionary changes to its economy and urban fabric, brought about by the Scottish Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution.

The city prospered from its involvement in the triangular trade and the Atlantic slave trade that the former depended upon. Glasgow merchants dealt in slave-produced cash crops such as sugar, tobacco, cotton and linen.[31][32] From 1717 to 1766, Scottish slave ships operating out of Glasgow transported approximately 3,000 enslaved Africans to the Americas (out of a total number of 5,000 slaves carried by ships from Scotland). The majority of these slaving voyages left from Glasgow's satellite ports, Greenock and Port Glasgow.[33]

Trading port

After the Acts of Union in 1707, Scotland gained further access to the vast markets of the new British Empire, and Glasgow became prominent as a hub of international trade to and from the Americas, especially in sugar, tobacco, cotton, and manufactured goods. Starting in 1668, the city's Tobacco Lords created a deep water port at Port Glasgow about 20 mi (32 km) down the River Clyde, as the river from the city to that point was then too shallow for seagoing merchant ships.[34] By the late 18th century more than half of the British tobacco trade was concentrated on the River Clyde, with over 47,000,000 lb (21,000 t) of tobacco being imported each year at its peak.[35] At the time, Glasgow held a commercial importance as the city participated in the trade of sugar, tobacco and later cotton.[36] From the mid-eighteenth century the city began expanding westwards from its medieval core at Glasgow Cross, with a grid-iron street plan starting from the 1770s and eventually reaching George Square to accommodate much of the growth, with that expansion much later becoming known in the 1980s onwards as the Merchant City.[37] The largest growth in the city centre area, building on the wealth of trading internationally, was the next expansion being the grid-iron streets west of Buchanan Street riding up and over Blythswood Hill from 1800 onwards.[38]

Industrialisation

The opening of the Monkland Canal and basin linking to the Forth and Clyde Canal at Port Dundas in 1795, facilitated access to the extensive iron-ore and coal mines in Lanarkshire. After extensive river engineering projects to dredge and deepen the River Clyde as far as Glasgow, shipbuilding became a major industry on the upper stretches of the river, pioneered by industrialists such as Robert Napier, John Elder, George Thomson, Sir William Pearce and Sir Alfred Yarrow. The River Clyde also became an important source of inspiration for artists, such as John Atkinson Grimshaw, John Knox, James Kay, Sir Muirhead Bone, Robert Eadie and L.S. Lowry, willing to depict the new industrial era and the modern world, as did Stanley Spencer downriver at Port Glasgow.

Glasgow's population had surpassed that of Edinburgh by 1821. The development of civic institutions included the City of Glasgow Police in 1800, one of the first municipal police forces in the world. Despite the crisis caused by the City of Glasgow Bank's collapse in 1878, growth continued and by the end of the 19th century it was one of the cities known as the "Second City of the Empire" and was producing more than half Britain's tonnage of shipping[39] and a quarter of all locomotives in the world.[40] In addition to its pre-eminence in shipbuilding, engineering, industrial machinery, bridge building, chemicals, explosives, coal and oil industries it developed as a major centre in textiles, garment-making, carpet manufacturing, leather processing, furniture-making, pottery, food, drink and cigarette making; printing and publishing. Shipping, banking, insurance and professional services expanded at the same time.[28]

Glasgow became one of the first cities in Europe to reach a population of one million. The city's new trades and sciences attracted new residents from across the Lowlands and the Highlands of Scotland, from Ireland and other parts of Britain and from Continental Europe.[28] During this period, the construction of many of the city's greatest architectural masterpieces and most ambitious civil engineering projects, such as the Milngavie water treatment works, Glasgow Subway, Glasgow Corporation Tramways, City Chambers, Mitchell Library and Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum were being funded by its wealth. The city also held a series of International Exhibitions at Kelvingrove Park, in 1888, 1901 and 1911, with Britain's last major International Exhibition, the Empire Exhibition, being subsequently held in 1938 at Bellahouston Park, which drew 13 million visitors.[41]

The 20th century witnessed both decline and renewal in the city. After World War I, the city suffered from the impact of the Post–World War I recession and from the later Great Depression, this also led to a rise of radical socialism and the "Red Clydeside" movement. The city had recovered by the outbreak of World War II. The city saw aerial bombardment by the Luftwaffe[42] during the Clydebank Blitz, during the war, then grew through the post-war boom that lasted through the 1950s. By the 1960s, growth of industry in countries like Japan and West Germany, weakened the once pre-eminent position of many of the city's industries. As a result of this, Glasgow entered a lengthy period of relative economic decline and rapid de-industrialisation, leading to high unemployment, urban decay, population decline, welfare dependency and poor health for the city's inhabitants. There were active attempts at regeneration of the city, when the Glasgow Corporation published its controversial Bruce Report, which set out a comprehensive series of initiatives aimed at turning round the decline of the city. The report led to a huge and radical programme of rebuilding and regeneration efforts that started in the mid-1950s and lasted into the late 1970s. This involved the mass demolition of the city's infamous slums and their replacement with large suburban housing estates and tower blocks.[43]

The city invested heavily in roads infrastructure, with an extensive system of arterial roads and motorways that bisected the central area. There are also accusations that the Scottish Office had deliberately attempted to undermine Glasgow's economic and political influence in post-war Scotland by diverting inward investment in new industries to other regions during the Silicon Glen boom and creating the new towns of Cumbernauld, Glenrothes, Irvine, Livingston and East Kilbride, dispersed across the Scottish Lowlands to halve the city's population base.[43] By the late 1980s, there had been a significant resurgence in Glasgow's economic fortunes. The "Glasgow's miles better" campaign, launched in 1983, and opening of the Burrell Collection in 1983 and Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre in 1985 facilitated Glasgow's new role as a European centre for business services and finance and promoted an increase in tourism and inward investment.[44] The latter continues to be bolstered by the legacy of the city's Glasgow Garden Festival in 1988, its status as European Capital of Culture in 1990,[45] and concerted attempts to diversify the city's economy.[46] However, it is the industrial heritage that serves as key tourism enabler.[47] Wider economic revival has persisted and the ongoing regeneration of inner-city areas, including the large-scale Clyde Waterfront Regeneration, has led to more affluent people moving back to live in the centre of Glasgow, fuelling allegations of gentrification.[48] In 2008, the city was listed by Lonely Planet as one of the world's top 10 tourist cities.[49]

Despite Glasgow's economic renaissance, the East End of the city remains the focus of social deprivation.[50] A Glasgow Economic Audit report published in 2007 stated that the gap between prosperous and deprived areas of the city is widening.[51] In 2006, 47% of Glasgow's population lived in the most deprived 15% of areas in Scotland,[51] while the Centre for Social Justice reported 29.4% of the city's working-age residents to be "economically inactive".[50] Although marginally behind the UK average, Glasgow still has a higher employment rate than Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester.[51] In 2008 the city was ranked at 43 for Personal Safety in the Mercer index of top 50 safest cities in the world.[52] The Mercer report was specifically looking at Quality of Living, yet by 2011 within Glasgow, certain areas were (still) "failing to meet the Scottish Air Quality Objective levels for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and particulate matter (PM10)".[53]

Sanitation

With the population growing, the first scheme to provide a public water supply was by the Glasgow Company in 1806. A second company was formed in 1812, and the two merged in 1838, but there was some dissatisfaction with the quality of the water supplied.[54] The Gorbals Gravitation Water Company began supplying water to residents living to the south of the River Clyde in 1846, obtained from reservoirs, which gave 75,000 people a constant water supply,[54] but others were not so fortunate, and some 4,000 died in an outbreak of cholera in 1848/1849.[55] This led to the development of the Glasgow Corporation Water Works, with a project to raise the level of Loch Katrine and to convey clean water by gravity along a 26 mi (42 km) aqueduct to a holding reservoir at Milngavie, and then by pipes into the city.[56] The project cost £980,000[55] and was opened by Queen Victoria in 1859.[57] In the early 19th century an eighth of the people lived in single-room accommodation.[58]

The engineer for the project was John Frederick Bateman, while James Morris Gale became the resident engineer for the city section of the project, and subsequently became Engineer in Chief for Glasgow Water Commissioners. He oversaw several improvements during his tenure, including a second aqueduct and further raising of water levels in Loch Katrine.[59] Additional supplies were provided by Loch Arklet in 1902, by impounding the water and creating a tunnel to allow water to flow into Loch Katrine. A similar scheme to create a reservoir in Glen Finglas was authorised in 1903, but was deferred, and was not completed until 1965.[55] Following the 2002 Glasgow floods, the waterborne parasite cryptosporidium was found in the reservoir at Milngavie, and so the new Milngavie water treatment works was built. It was opened by Queen Elizabeth in 2007, and won the 2007 Utility Industry Achievement Award, having been completed ahead of its time schedule and for £10 million below its budgeted cost.[60]

Good health requires both clean water and effective removal of sewage. The Caledonian Railway rebuilt many of the sewers, as part of a deal to allow them to tunnel under the city, and sewage treatment works were opened at Dalmarnoch in 1894, Dalmuir in 1904 and Shieldhall in 1910. The works experimented to find better ways to treat sewage, and a number of experimental filters were constructed, until a full activated sludge plant was built between 1962 and 1968 at a cost of £4 million.[61] Treated sludge was dumped at sea, and Glasgow Corporation owned six sludge ships between 1904 and 1998,[62] when the EU Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive ended the practice.[63] The sewerage infrastructure was improved significantly in 2017, with the completion of a tunnel 3.1 mi (5.0 km) long, which provides 20×106 imp gal (90 Ml) of storm water storage. It will reduce the risk of flooding and the likelihood that sewage will overflow into the Clyde during storms.[64] Since 2002, clean water provision and sewerage have been the responsibility of Scottish Water.[65]

Government and politics

Local government

Although Glasgow Corporation had been a pioneer in the municipal socialist movement from the late-nineteenth century, since the Representation of the People Act 1918, Glasgow increasingly supported left-wing ideas and politics at a national level. The city council was controlled by the Labour Party for over thirty years, since the decline of the Progressives. Since 2007, when local government elections in Scotland began to use the single transferable vote rather than the first-past-the-post system, the dominance of the Labour Party within the city started to decline. As a result of the 2017 United Kingdom local elections, the SNP was able to form a minority administration ending Labour's thirty-seven years of uninterrupted control.[66]

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the German Revolution of 1918–19, the city's frequent strikes and militant organisations caused serious alarm at Westminster, with one uprising in January 1919 prompting the Liberal Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, to deploy 10,000 soldiers and tanks on the city's streets. A huge demonstration in the city's George Square on 31 January ended in violence after the Riot Act was read.[67]

Industrial action at the shipyards gave rise to the "Red Clydeside" epithet. During the 1930s, Glasgow was the main base of the Independent Labour Party. Towards the end of the twentieth century, it became a centre of the struggle against the poll tax; which was introduced in Scotland a whole year before the rest of the United Kingdom and also served as the main base of the Scottish Socialist Party, another left-wing political party in Scotland. The city has not had a Conservative MP since the 1982 Hillhead by-election, when the SDP took the seat, which was in Glasgow's most affluent area. The fortunes of the Conservative Party continued to decline into the twenty-first century, winning only one of the 79 councillors on Glasgow City Council in 2012, despite having been the controlling party (as the Progressives) from 1969 to 1972 when Sir Donald Liddle was the last non-Labour Lord Provost.[68]

Glasgow is represented in both the House of Commons in London, and the Scottish Parliament in Holyrood, Edinburgh. At Westminster, it is represented by seven Members of Parliament (MPs), all elected at least once every five years to represent individual constituencies, using the first-past-the-post system of voting. In Holyrood, Glasgow is represented by sixteen Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs), of whom nine are elected to represent individual constituencies once every four years using first-past-the-post, and seven are elected as additional regional members, by proportional representation. Since the 2016 Scottish Parliament election, Glasgow is represented at Holyrood by 9 Scottish National Party MSPs, 4 Labour MSPs, 2 Conservative MSPs and 1 Scottish Green MSP. In the European Parliament, the city formed part of the Scotland constituency, which elected six Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) prior to Brexit.[69]

Central government

Since Glasgow is covered and operates under two separate central governments, the devolved Scottish Parliament and UK Government, they determine various matters that Glasgow City Council is not responsible for.

The Glasgow electoral region of the Scottish Parliament covers the Glasgow City council area, a north-western part of South Lanarkshire and a small eastern portion of Renfrewshire. It elects nine of the parliament's 73 first past the post constituency members and seven of the 56 additional members. Both kinds of member are known as Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs). The system of election is designed to produce a form of proportional representation.[70]

The first past the post seats were created in 1999 with the names and boundaries of then existing Westminster (House of Commons) constituencies. In 2005, the number of Westminster Members of Parliament (MPs) representing Scotland was cut to 59, with new constituencies being formed, while the existing number of MSPs was retained at Holyrood. In the 2011 Scottish Parliament election, the boundaries of the Glasgow region were redrawn.[71]

Currently, the nine Scottish Parliament constituencies in the Glasgow electoral region are:

- Glasgow Anniesland

- Glasgow Cathcart Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Glasgow_City_(council_area)

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk