A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germany, and at times other parts of Europe, the beliefs and practices of Germanic paganism varied. Scholars typically assume some degree of continuity between Roman-era beliefs and those found in Norse paganism, as well as between Germanic religion and reconstructed Indo-European religion and post-conversion folklore, though the precise degree and details of this continuity are subjects of debate. Germanic religion was influenced by neighboring cultures, including that of the Celts, the Romans, and, later, by the Christian religion. Very few sources exist that were written by pagan adherents themselves; instead, most were written by outsiders and can thus present problems for reconstructing authentic Germanic beliefs and practices.

Some basic aspects of Germanic belief can be reconstructed, including the existence of one or more origin myths, the existence of a myth of the end of the world, a general belief in the inhabited world being a "middle-earth", as well as some aspects of belief in fate and the afterlife. The Germanic peoples believed in a multitude of gods, and in other supernatural beings such as jötnar (often glossed as giants), dwarfs, elves, and dragons. Roman-era sources, using Roman names, mention several important male gods, as well as several goddesses such as Nerthus and the matronae. Early medieval sources identify a pantheon consisting of the gods *Wodanaz (Odin), *Thunraz (Thor), *Tiwaz (Tyr), and *Frijjō (Frigg),[a] as well as numerous other gods, many of whom are only attested from Norse sources (see Proto-Germanic folklore).

Textual and archaeological sources allow the reconstruction of aspects of Germanic ritual and practice. These include well-attested burial practices, which likely had religious significance, such as rich grave goods and the burial in ships or wagons. Wooden carved figures that may represent gods have been discovered in bogs throughout northern Europe, and rich sacrificial deposits, including objects, animals, and human remains, have been discovered in springs, bogs, and under the foundations of new structures. Evidence for sacred places includes not only natural locations such as sacred groves but also early evidence for the construction of structures such as temples and the worship of standing poles in some places. Other known Germanic religious practices include divination and magic, and there is some evidence for festivals and the existence of priests.

Subject and terminology

Definition

Germanic religion is principally defined as the religious traditions of speakers of Germanic languages (the Germanic peoples).[2] The term "religion" in this context is itself controversial, Bernhard Maier noting that it "implies a specifically modern point of view, which reflects the modern conceptual isolation of 'religion' from other aspects of culture".[3] Never a unified or codified set of beliefs or practices, Germanic religion showed strong regional variations and Rudolf Simek writes that it is better to refer to "Germanic religions".[4] In many contact areas (e.g. Rhineland and eastern and northern Scandinavia), Germanic paganism was similar to neighboring religions such as those of the Slavs, Celts, or Finnic peoples.[5] The use of the qualifier "Germanic" (e.g. "Germanic religion" and its variants) remains common in German-language scholarship, but is less commonly used in English and other scholarly languages, where scholars usually specify which branch of paganism is meant (e.g. Norse paganism or Anglo-Saxon paganism).[6] The term "Germanic religion" is sometimes applied to practices dating to as early as the Stone Age or Bronze Age, but its use is more generally restricted to the time period after the Germanic languages had become distinct from other Indo-European languages (early Iron Age). Germanic paganism covers a period of around one thousand years in terms of written sources, from the first reports in Roman sources to the final conversion to Christianity.[7]

Continuity

Because of the amount of time and space covered by the term "Germanic religion", controversy exists as to the degree of continuity of beliefs and practices between the earliest attestations in Tacitus and the later attestations of Norse paganism from the high Middle Ages. Many scholars argue for continuity, seeing evidence of commonalities between the Roman, early medieval, and Norse attestations, while many other scholars are skeptical.[9] The majority of Germanic gods attested by name during the Roman period cannot be related to a later Norse god; many names attested in the Nordic sources are similarly without any known non-Nordic equivalents.[10][11] The much higher number of sources on Scandinavian religion has led to a methodologically problematic tendency to use Scandinavian material to complete and interpret the much more sparsely attested information on continental Germanic religion.[12]

Most scholars accept some form of continuity between Indo-European and Germanic religion,[13] but the degree of continuity is a subject of controversy.[14] Jens Peter Schjødt writes that while many scholars view comparisons of Germanic religion with other attested Indo-European religions positively, "just as many, or perhaps even more, have been sceptical".[15] While supportive of Indo-European comparison, Schjødt notes that the "dangers" of comparison are taking disparate elements out of context and arguing that myths and mythical structures found around the world must be Indo-European just because they appear in multiple Indo-European cultures.[16] Bernhard Maier argues that similarities with other Indo-European religions do not necessarily result from a common origin, but can also be the result of convergence.[17]

Continuity also concerns the question of whether popular, post-conversion beliefs and practices (folklore) found among Germanic speakers up to the modern day reflect a continuity with earlier Germanic religion. Earlier scholars, beginning with Jacob Grimm, believed that modern folklore was of ancient origin and had changed little over the centuries, which allowed the use of folklore and fairy tales as sources of Germanic religion.[18][19] These ideas later came under the influence of völkisch ideology, which stressed the organic unity of a Germanic "national spirit" (Volksgeist), as expressed in Otto Höfler's "Germanic continuity theory".[20][21] As a result, the use of folklore as a source went out of fashion after World War II, especially in Germany,[22] but has experienced a revival since the 1990s in Nordic scholarship.[23] Today, scholars are cautious in their use of folkloric material, keeping in mind that most was collected long after the conversion and the advent of writing.[24] Areas where continuity can be noted include agrarian rites and magical ideas,[23] as well as the root elements of some folktales.[25]

Sources

Sources on Germanic religion can be divided between primary sources and secondary sources. Primary sources include texts, structures, place names, personal names, and objects that were created by devotees of the religion; secondary sources are normally texts that were written by outsiders.[27]

Primary sources

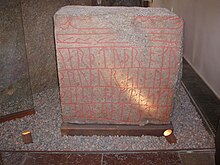

Examples of primary sources include some Latin alphabet and Runic inscriptions, as well as poetic texts such as the Merseburg Charms and heroic texts that may date from pagan times, but were written down by Christians.[28] The poems of the Edda, while pagan in origin, continued to circulate orally in a Christian context before being written down, which makes an application to pre-Christian times difficult.[12] In contrast, pre-Christian images such as on bracteates, gold foil figures, and rune and picture stones are direct attestations of Germanic religion. The interpretation of these images is not always immediately obvious.[29] Archaeological evidence is also extensive, including evidence from burials and sacrificial sites.[30] Ancient votive altars from the Rhineland often contain inscriptions naming gods with Germanic or partially Germanic names.[31]

Secondary sources

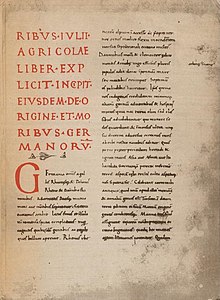

Most textual sources on Germanic religion were written by outsiders.[12] The chief textual source for Germanic religion in the Roman period is Tacitus's Germania.[33][b] There are problems with Tacitus's work, however, as it is unclear how much he really knew about the Germanic peoples he described and because he employed numerous topoi dating back to Herodotus that were used when describing a barbarian people.[35] Tacitus' reliability as a source can be characterized by his rhetorical tendencies, since one of the purposes of Germania was to present his Roman compatriots with an example of the virtues he believed they lacked.[36] Julius Caesar, Procopius, and other ancient authors also offer some information on Germanic religion.[37][c]

Textual sources for post-Roman continental Germanic religion are written by Christian authors: Some of the gods of the Lombards are described in the 7th-century Origo gentis Langobardorum ("Origin of the Lombard People"), while a small amount of information on the religion of the pagan Franks can be found in Gregory of Tours's late 6th-century Historia Francorum ("History of the Franks").[39] An important source for the pre-Christian religion of the Anglo-Saxons is Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (c. 731).[40] Other sources include historians such as Jordanes (6th century CE) and Paul the Deacon (8th century), as well as saint lives and Christian legislation against various practices.[37]

Textual sources for Scandinavian religion are much more extensive. They include the aforementioned poems of the Poetic Edda, Eddic poetry found in other sources, the Prose Edda, which is usually attributed to the Icelander Snorri Sturluson (13th century CE), Skaldic poetry, poetic kennings with mythological content, Snorri's Heimskringla, the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus (12th-13th century CE), Icelandic historical writing and sagas, as well as outsider sources such as the report on the Rus' made by the Arab traveler Ahmad ibn Fadlan (10th century), the Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum by bishop Adam of Bremen (11th century CE), and various saints' lives.[41][42]

Outside influences and syncretism

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Germanic_PaganismText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk