A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (May 2022) |

| Finnish | |

|---|---|

| suomi | |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [ˈsuo̯mi] ⓘ |

| Native to | Finland, Sweden, Norway (in small areas in Troms and Finnmark), Russia |

| Ethnicity | Finns |

Native speakers | 5.8 million Finland: 5.4 million Sweden: 0.40 million Norway: 8,000 (Kven) Russia (Karelia): 8,500 US: 26,000 (2020)[1] |

Uralic

| |

| Dialects | |

| Latin (Finnish alphabet) Finnish Braille | |

| Signed Finnish | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Language Planning Department of the Institute for the Languages of Finland |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | fi |

| ISO 639-2 | fin |

| ISO 639-3 | fin |

| Glottolog | nucl1717 |

| Linguasphere | 41-AAA-a |

| |

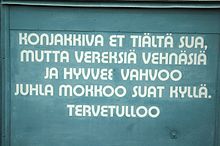

Finnish (endonym: suomi [ˈsuo̯mi] ⓘ or suomen kieli [ˈsuo̯meŋ ˈkie̯li]) is a Uralic language of the Finnic branch, spoken by the majority of the population in Finland and by ethnic Finns outside of Finland. Finnish is one of the two official languages of Finland (the other being Swedish). In Sweden, both Finnish and Meänkieli (which has significant mutual intelligibility with Finnish[3]) are official minority languages. The Kven language, which like Meänkieli is mutually intelligible with Finnish, is spoken in the Norwegian counties Troms and Finnmark by a minority group of Finnish descent.

Finnish is typologically agglutinative[4] and uses almost exclusively suffixal affixation. Nouns, adjectives, pronouns, numerals and verbs are inflected depending on their role in the sentence. Sentences are normally formed with subject–verb–object word order, although the extensive use of inflection allows them to be ordered differently. Word order variations are often reserved for differences in information structure.[5] Finnish orthography uses a Latin-script alphabet derived from the Swedish alphabet, and is phonetic to a great extent. Vowel length and consonant length are distinguished, and there are a range of diphthongs, although vowel harmony limits which diphthongs are possible.

Classification

Finnish is a member of the Finnic group of the Uralic family of languages; as such, it is one of the few European languages that is not Indo-European. The Finnic group also includes Estonian and a few minority languages spoken around the Baltic Sea and in Russia's Republic of Karelia.

Finnish demonstrates an affiliation with other Uralic languages (such as Hungarian) in several respects including:

- Shared morphology:

- case suffixes such as genitive -n, partitive -(t)a / -(t)ä ( < Proto-Uralic *-ta, originally ablative), essive -na / -nä ( < *-na, originally locative)

- plural markers -t and -i- ( < Proto-Uralic *-t and *-j, respectively)

- possessive suffixes such as 1st person singular -ni ( < Proto-Uralic *-n-mi), 2nd person singular -si ( < Proto-Uralic *-ti).

- various derivational suffixes (e.g. causative -tta/-ttä < Proto-Uralic *-k-ta)

- Shared basic vocabulary displaying regular sound correspondences with the other Uralic languages (e.g. kala 'fish' ~ North Saami guolli ~ Hungarian hal; and kadota 'disappear' ~ North Saami guođđit ~ Hungarian hagy 'leave (behind)'.

Several theories exist as to the geographic origin of Finnish and the other Uralic languages. The most widely held view is that they originated as a Proto-Uralic language somewhere in the boreal forest belt around the Ural Mountains region and/or the bend of the middle Volga. The strong case for Proto-Uralic is supported by common vocabulary with regularities in sound correspondences, as well as by the fact that the Uralic languages have many similarities in structure and grammar.[6]

The Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, United States, classifies Finnish as a level III language (of four levels) in terms of learning difficulty for native English speakers.[7]

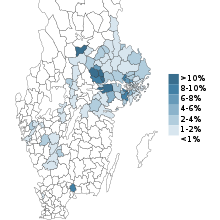

Geographic distribution

Finnish is spoken by about five million people, most of whom reside in Finland. There are also notable Finnish-speaking minorities in Sweden, Norway, Russia, Estonia, Brazil, Canada, and the United States. The majority of the population of Finland (90.37% as of 2010[update][9]) speak Finnish as their first language. The remainder speak Swedish (5.42%),[9] one of the Sámi languages (for example Northern, Inari, or Skolt), or another language as their first language. Finnish is spoken as a second language in Estonia by about 167,000 people.[10] The varieties of Finnish found in Norway's Finnmark (namely Kven) and in northern Sweden (namely Meänkieli) have the status of official minority languages, and thus can be considered distinct languages from Finnish. However, since all three are mutually intelligible, one may alternatively view them as dialects of the same language.

There are also forms of Finnish spoken by diasporas in Siberia, by the Siberian Finns[11] and in America, where American Finnish is spoken by Finnish Americans.[12]

In the latest census, around 1000 people in Russia claimed to speak Finnish natively; however, a larger amount of 14,000 claimed to be able to speak Finnish in total.[13]

No language census exists for Norway, neither for Kven, standard Finnish, or combined. As of 2023, 7,454 first- or second-generation immigrants from Finland were registered as having Norwegian residency,[14] while as of 2021, 235 Finns were registered as foreigners studying at Norwegian higher education.[15] Great Norwegian Encyclopedia estimates Kven speakers at 2,000-8,000.[16] Altogether, this results in a total amount of Finnish-speakers roughly between 7,200 and 15,600.

Official status

Today, Finnish is one of two official languages of Finland (the other being Swedish), and has been an official language of the European Union since 1995. However, the Finnish language did not have an official status in the country during the period of Swedish rule, which ended in 1809. After the establishment of the Grand Duchy of Finland, and against the backdrop of the Fennoman movement, the language obtained its official status in the Finnish Diet of 1863.[17]

Finnish also enjoys the status of an official minority language in Sweden. Under the Nordic Language Convention, citizens of the Nordic countries speaking Finnish have the opportunity to use their native language when interacting with official bodies in other Nordic countries without being liable to any interpretation or translation costs.[18][19] However, concerns have been expressed about the future status of Finnish in Sweden, for example, where reports produced for the Swedish government during 2017 show that minority language policies are not being respected, particularly for the 7% of Finns settled in the country.[20]

History

Prehistory

The Uralic family of languages, of which Finnish is a member, are hypothesized to derive from a single ancestor language termed Proto-Uralic, spoken sometime between 8,000 and 2,000 BCE (estimates vary) in the vicinity of the Ural mountains.[21] Over time, Proto-Uralic split into various daughter languages, which themselves continued to change and diverge, yielding yet more descendants. One of these descendants is the reconstructed Proto-Finnic, from which the Finnic languages developed.[22]

Current models assume that three or more Proto-Finnic dialects evolved during the first millennium BCE.[23][22] These dialects were defined geographically, and were distinguished from one another along a north–south split as well as an east–west split. The northern dialects of Proto-Finnic, from which Finnish developed, lacked the mid vowel [ɤ]. This vowel was found only in the southern dialects, which developed into Estonian, Livonian, and Votian. The northern variants used third person singular pronoun hän instead of southern tämä (Est. tema). While the eastern dialects of Proto-Finnic (which developed in the modern-day eastern Finnish dialects, Veps, Karelian, and Ingrian) formed genitive plural nouns via plural stems (e.g., eastern Finnish kalojen < *kaloi-ten), the western dialects of Proto-Finnic (today's Estonian, Livonian and western Finnish varieties) used the non-plural stems (e.g., Est. kalade < *kala-ten). Another defining characteristic of the east–west split was the use of the reflexive suffix -(t)te, used only in the eastern dialects.[22]

Medieval period

The birch bark letter 292 from the early 13th century is the first known document in any Finnic language. The first known written example of Finnish itself is found in a German travel journal dating back to c. 1450: Mÿnna tachton gernast spuho sommen gelen Emÿna daÿda (Modern Finnish: "Minä tahdon kernaasti puhua suomen kielen, en minä taida;" English: "I want to speak Finnish, I am not able to").[24] According to the travel journal, the words are those of a Finnish bishop whose name is unknown. The erroneous use of gelen (Modern Finnish kielen) in the accusative case, rather than kieltä in the partitive, and the lack of the conjunction mutta are typical of foreign speakers of Finnish even today.[25] At the time, most priests in Finland spoke Swedish.[26]

During the Middle Ages, when Finland was under Swedish rule, Finnish was only spoken. At the time, the language of international commerce was Middle Low German, the language of administration Swedish, and religious ceremonies were held in Latin. This meant that Finnish speakers could use their mother tongue only in everyday life. Finnish was considered inferior to Swedish, and Finnish speakers were second-class members of society because they could not use their language in any official situations. There were even efforts to reduce the use of Finnish through parish clerk schools, the use of Swedish in church, and by having Swedish-speaking servants and maids move to Finnish-speaking areas.[27]

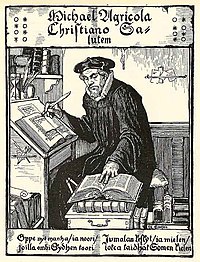

Writing system

The first comprehensive writing system for Finnish was created by Mikael Agricola, a Finnish bishop, in the 16th century. He based his writing system on the western dialects. Agricola's ultimate plan was to translate the Bible,[28] but first he had to develop an orthography for the language, which he based on Swedish, German, and Latin. The Finnish standard language still relies on his innovations with regard to spelling, though Agricola used less systematic spelling than is used today.[29]

Though Agricola's intention was that each phoneme (and allophone under qualitative consonant gradation) should correspond to one letter, he failed to achieve this goal in various respects. For example, k, c, and q were all used for the phoneme /k/. Likewise, he alternated between dh and d to represent the allophonic [ð] (like th in English this), between dh and z to represent /θː/ (like th in thin, but longer in duration), and between gh and g to represent the allophonic [ɣ]. Agricola did not consistently represent vowel length in his orthography.[29]

Others revised Agricola's work later, striving for a more systematic writing system. Along the way, Finnish lost several fricative consonants in a process of sound change. The sounds and disappeared from the language, surviving only in a small rural region in Western Finland.[30] In the standard language, however, the effect of the lost sounds is thus:

- became . The sound was written ⟨d⟩ or ⟨dh⟩ by Agricola. This sound was lost from most varieties of Finnish, either losing all phonetic realization or being pronounced as , , , or instead (depending on dialect and the position in the word). However, Agricola's spelling ⟨d⟩ prevailed, and the pronunciation in Standard Finnish became through spelling pronunciation.[29]

- became ts. These interdental fricatives were written as ⟨tz⟩ (for both grades: geminate and short) in some of the earliest written records. Though these developed into a variety of other sounds depending on dialect (tː, t, ht, h, ht, t, sː, s, tː, tː, or ht, ht), the standard language has arrived at spelling pronunciation ts (which is treated as a consonant cluster and hence not subject to consonant gradation).

- ɣ became:

- ʋ if it appeared originally between high round vowels u and y (cf. suku 'kin, family' : suvun genitive form from earlier *suku : *suɣun, and kyky : kyvyn 'ability, skill' nominative and genitive, respectively from *kükü : *küɣün, contrasting with sika : sian 'pig, pork' nominative and genitive from *sika : *siɣan. A similar process explains the /f/ pronunciation for some English words with "gh", such as "tough"),

- j between a liquid consonant l or r and a vowel e (like in kuljen 'I go', a form of the verb kulkea 'to go' that was originally *kulɣen),

- and otherwise it was lost entirely.

Modern Finnish punctuation, along with that of Swedish, uses the colon (:) to separate the stem of a word and its grammatical ending in some cases, for example after acronyms, as in EU:ssa 'in the EU'. (This contrasts with some other alphabetic writing systems, which would use other symbols, such as e.g. apostrophe, hyphen.) Since suffixes play a prominent role in the language, this use of the colon is quite common.

Modernizationedit

In the 19th century Johan Vilhelm Snellman and others began to stress the need to improve the status of Finnish. Ever since the days of Mikael Agricola, written Finnish had been used almost exclusively in religious contexts, but now Snellman's Hegelian nationalistic ideas of Finnish as a fully-fledged national language gained considerable support. Concerted efforts were made to improve the status of the language and to modernize it, and by the end of the century Finnish had become a language of administration, journalism, literature, and science in Finland, along with Swedish.

In 1853 Daniel Europaeus published the first Swedish-Finnish dictionary,[31] and between 1866 and 1880 Elias Lönnrot compiled the first Finnish-Swedish dictionary.[32] In the same period, Antero Warelius conducted ethnographic research and, among other topics, he documented the geographic distribution of the Finnish dialects.[33]

The most important contributions to improving the status of Finnish were made by Elias Lönnrot. His impact on the development of modern vocabulary in Finnish was particularly significant. In addition to compiling the Kalevala, he acted as an arbiter in disputes about the development of standard Finnish between the proponents of western and eastern dialects, ensuring that the western dialects preferred by Agricola retained their preeminent role, while many originally dialect words from Eastern Finland were introduced to the standard language, thus enriching it considerably.[34] The first novel written in Finnish (and by a Finnish speaker) was Seven Brothers (Seitsemän veljestä), published by Aleksis Kivi in 1870.

Dialectsedit

The dialects of Finnish are divided into two distinct groups, Western and Eastern.[35] The dialects are largely mutually intelligible and are distinguished from each other by changes in vowels, diphthongs and rhythm, as well as in preferred grammatical constructions. For the most part, the dialects operate on the same phonology and grammar. There are only marginal examples of sounds or grammatical constructions specific to some dialect and not found in standard Finnish. Two examples are the voiced dental fricative found in the Rauma dialect, and the Eastern exessive case.

The classification of closely related dialects spoken outside Finland is a politically sensitive issue that has been controversial since Finland's independence in 1917. This concerns specifically the Karelian language in Russia and Meänkieli in Sweden, the speakers of which are often considered oppressed minorities. Karelian is different enough from standard Finnish to have its own orthography. Meänkieli is a northern dialect almost entirely intelligible to speakers of any other Finnish dialect, which achieved its status as an official minority language in Sweden for historical and political reasons, although Finnish is an official minority language in Sweden, too. In 1980, many texts, books and the Bible were translated into Meänkieli and it has been developing more into its own language.[36]

Western dialectsedit

The Southwest Finnish dialects (lounaissuomalaismurteet) are spoken in Southwest Finland and Satakunta. Their typical feature is abbreviation of word-final vowels, and in many respects they resemble Estonian. The Tavastian dialects (hämäläismurteet) are spoken in Tavastia. They are closest to the standard language, but feature some slight vowel changes, such as the opening of diphthong-final vowels (tie → tiä, miekka → miakka, kuolisi → kualis), the change of d to l (mostly obsolete) or trilled r (widespread, nowadays disappearance of d is popular) and the personal pronouns (me: meitin ('we: our'), te: teitin ('you: your') and he: heitin ('they: their')). The South Ostrobothnian dialects (eteläpohjalaismurteet) are spoken in Southern Ostrobothnia. Their most notable feature is the pronunciation of "d" as a tapped or even fully trilled /r/. The Central and North Ostrobothnian dialects (keski- ja pohjoispohjalaismurteet) are spoken in Central and Northern Ostrobothnia. The Lapland dialects (lappilaismurteet) are spoken in Lapland. The dialects spoken in the western parts of Lapland are recognizable by retention of old "h" sounds in positions where they have disappeared from other dialects.

One form of speech related to Northern dialects, Meänkieli, which is spoken on the Swedish side of the border, is taught in some Swedish schools as a distinct standardized language. The speakers of Meänkieli became politically separated from the other Finns when Finland was annexed to Russia in 1809. The categorization of Meänkieli as a separate language is controversial among some Finns, who see no linguistic criteria, only political reasons, for treating Meänkieli differently from other dialects of Finnish.[38]

The Kven language is spoken in Finnmark and Troms, in Norway. Its speakers are descendants of Finnish emigrants to the region in the 18th and 19th centuries. Kven is an official minority language in Norway.

Eastern dialectsedit

The Eastern dialects consist of the widespread Savonian dialects (savolaismurteet) spoken in Savo and nearby areas, and the South-Eastern dialects now spoken only in Finnish South Karelia. The South Karelian dialects (eteläkarjalaismurteet) were previously also spoken on the Karelian Isthmus and in Ingria. The Karelian Isthmus was evacuated during World War II and refugees were resettled all over Finland. Most Ingrian Finns were deported to various interior areas of the Soviet Union.

Palatalization, a common feature of Uralic languages, had been lost in the Finnic branch, but it has been reacquired by most of these languages, including Eastern Finnish, but not Western Finnish. In Finnish orthography, this is denoted with a "j", e.g. vesj vesʲ "water", cf. standard vesi vesi.

The language spoken in those parts of Karelia that have not historically been under Swedish or Finnish rule is usually called the Karelian language, and it is considered to be more distant from standard Finnish than the Eastern dialects. Whether this language of Russian Karelia is a dialect of Finnish or a separate language is sometimes disputed.

Helsinki slang (Stadin slangi)edit

The first known written account in Helsinki slang is from the 1890 short story Hellaassa by young Santeri Ivalo (words that do not exist in, or deviate from, the standard spoken Finnish of its time are in bold):

Kun minä eilen illalla palasin labbiksesta, tapasin Aasiksen kohdalla Supiksen, ja niin me laskeusimme tänne Espikselle, jossa oli mahoton hyvä piikis. Mutta me mentiin Studikselle suoraan Hudista tapaamaan, ja jäimme sinne pariksi tunniksi, kunnes ajoimme Kaisikseen.[39]

Dialect chart of Finnishedit

- Finnish dialects

- Western dialects

- Southwest Finnish dialects

- Proper Finnish dialects

- Northern dialect group

- Southern dialect group

- Southwest Finnish middle dialects

- Pori region dialects

- Ala-Satakunta dialects

- dialects of Turku highlands

- Somero region dialects

- Western Uusimaa dialects

- Helsinki slang\dialects

- Proper Finnish dialects

- Tavastian Dialects

- Ylä-Satakunta dialects

- Heart Tavastian dialects

- Southern Tavastian dialects

- Southern-Eastern Tavastian dialects

- Hollola dialect group

- Porvoo dialect group

- Iitti dialect group

- South Ostrobothnian dialects

- Central and North Ostrobothnian dialects

- Central Ostrobothnian dialects

- North Ostrobothnian dialects

- Peräpohjola dialects

- Torne dialects ("Meänkieli" in Sweden)

- Kemi dialects

- Kemijärvi dialects

- Gällivare dialects ("Meänkieli" in Sweden)

- Finnmark dialects ("Kven language" in Northern Norway)

- Southwest Finnish dialects

- Eastern dialects

- Savonian dialects

- North Savonian dialects

- South Savonian dialects

- Middle dialects of Savonlinna region

- East Savonian dialects or North Karelian dialects

- Kainuu dialects

- Central Finland dialects

- Päijänne Tavastia dialects

- Keuruu-Evijärvi dialects

- Savonian dialects of Värmland (Värmland, Sweden and Innlandet, Norway; extinct)

- South Karelian dialects

- Proper South Karelian dialects

- Middle dialects of Lemi region

- Dialects of Ingria (in Russia)[42]

- Savonian dialects

- Western dialects

Linguistic registersedit

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2009) |

There are two main registers of Finnish used throughout the country. One is the "standard language" (yleiskieli), and the other is the "spoken language" (puhekieli). The standard language is used in formal situations like political speeches and newscasts. Its written form, the "book language" (kirjakieli), is used in nearly all written texts, not always excluding even the dialogue of common people in popular prose.[43] The spoken language, on the other hand, is the main variety of Finnish used in popular TV and radio shows and at workplaces, and may be preferred to a dialect in personal communication.

Standardizationedit

Standard Finnish is prescribed by the Language Office of the Research Institute for the Languages of Finland and is the language used in official communication. The Dictionary of Contemporary Finnish (Nykysuomen sanakirja 1951–61), with 201,000 entries, was a prescriptive dictionary that defined official language. An additional volume for words of foreign origin (Nykysuomen sivistyssanakirja, 30,000 entries) was published in 1991. An updated dictionary, The New Dictionary of Modern Finnish (Kielitoimiston sanakirja) was published in an electronic form in 2004 and in print in 2006. A descriptive grammar (the Large grammar of Finnish, Iso suomen kielioppi,[44] 1,600 pages) was published in 2004. There is also an etymological dictionary, Suomen sanojen alkuperä, published in 1992–2000, and a handbook of contemporary language (Nykysuomen käsikirja). Standard Finnish is used in official texts and is the form of language taught in schools. Its spoken form is used in political speech, newscasts, in courts, and in other formal situations. Nearly all publishing and printed works are in standard Finnish.

Colloquial Finnishedit

The colloquial language has mostly developed naturally from earlier forms of Finnish, and spread from the main cultural and political centres. The standard language, however, has always been a consciously constructed medium for literature. It preserves grammatical patterns that have mostly vanished from the colloquial varieties and, as its main application is writing, it features complex syntactic patterns that are not easy to handle when used in speech. The colloquial language develops significantly faster, and the grammatical and phonological changes also include the most common pronouns and suffixes, which amount to frequent but modest differences. Some sound changes have been left out of the formal language. For example, irregular verbs have developed in the spoken language as a result of the elision of sonorants in some verbs of the Type III class (with subsequent vowel assimilation), but only when the second syllable of the word is short. The result is that some forms in the spoken language are shortened, e.g. tule-n → tuu-n ('I come'), while others remain identical to the standard language hän tulee "he comes", never *hän tuu). However, the longer forms such as tule can be used in spoken language in other forms as well.

The literary language certainly still exerts a considerable influence upon the spoken word, because illiteracy is nonexistent and many Finns are avid readers. In fact, it is still not entirely uncommon to meet people who "talk book-ish" (puhuvat kirjakieltä); it may have connotations of pedantry, exaggeration, moderation, weaseling or sarcasm (somewhat like heavy use of Latinate words in English, or more old-fashioned or "pedantic" constructions: compare the difference between saying "There's no children I'll leave it to" and "There are no children to whom I shall leave it"). More common is the intrusion of typically literary constructions into a colloquial discourse, as a kind of quote from written Finnish. It is quite common to hear book-like and polished speech on radio or TV, and the constant exposure to such language tends to lead to the adoption of such constructions even in everyday language.

A prominent example of the effect of the standard language is the development of the consonant gradation form /ts : ts/ as in metsä : metsän, as this pattern was originally (1940) found natively only in the dialects of the southern Karelian isthmus and Ingria. It has been reinforced by the spelling "ts" for the dental fricative θː, used earlier in some western dialects. The spelling and the pronunciation this encourages however approximate the original pronunciation, still reflected in e.g. Karelian /čč : č/ (meččä : mečän). In the spoken language, a fusion of Western /tt : tt/ (mettä : mettän) and Eastern /ht : t/ (mehtä : metän) has resulted in /tt : t/ (mettä : metän).[45] Neither of these forms are identifiable as, or originate from, a specific dialect.

The orthography of informal language follows that of the formal. However, in signalling the former in writing, syncope and sandhi – especially internal – may occasionally amongst other characteristics be transcribed, e.g. menenpä → me(n)empä. This never occurs in the standard variety.

Examplesedit

formal language colloquial language meaning notes hän menee he menevät

se menee ne menee

"he/she goes" "they go"

loss of an animacy contrast in pronouns (ne and se are inanimate in the formal language), and loss of a number contrast on verbs in the 3rd person (menee is 3rd person singular in the formal language)

minä, minun, ... mä(ä)/mie, mun/miun, ... "I, my, ..." various alternative, usually shorter, forms of 1st and 2nd person pronouns (minä) tulen (minä) olen

mä tuun mä oon

"I'm coming" or "I will come" "I am" or "I will be"

elision of sonorants before short vowels in certain Type III verbs along with vowel assimilation, and no pro-drop (i.e., personal pronouns are usually mandatory in the colloquial language)

onko teillä eikö teillä ole

o(n)ks teil(lä) e(i)ks teil(lä) oo

"do you (pl.) have?" "don't you (pl.) have (it)?"

vowel apocope and common use of the clitic -s in interrogatives (compare eiks to standard Estonian confirmatory interrogative eks)

(me) emme sano me ei sanota "we don't say" or "we won't say" the passive voice is used in place of the first person plural (minun) kirjani mun kirja "my book" lack of possessive clitics on nouns (minä) en tiedä syödä

mä en ti(i)ä syyä

"I don't know" "to eat"

elision of d between vowels, and subsequent vowel assimilation (compare mä en ti(i)ä to standard Estonian ma ei tea or dialectal forms ma ei tia or ma ei tie)

kuusikymmentäviisi kuuskyt(ä)viis "sixty-five" abbreviated forms of numerals punainen ajoittaa

punane(n) ajottaa

"red" "to time"

unstressed diphthongs ending in /i/ become short vowels, and apocope of phrase-final -n korjannee kai korjaa "probably will fix" absence of the potential mood, use of kai 'probably' instead

There are noticeable differences between dialects. Here the formal language does not mean a language spoken in formal occasions but the standard language which exists practically only in written form.

Phonologyedit

Segmental phonologyedit

The phoneme inventory of Finnish is moderately small,[46] with a great number of vocalic segments and a restricted set of consonant types, both of which can be long or short.

Vocalic segmentsedit

Finnish monophthongs show eight vowel qualities that contrast in duration, thus 16 vowel phonemes in total. Vowel allophony is quite restricted. Vowel phonemes are always contrastive in word-initial syllables; for non-initial syllable, see morphophonology below. Long and short vowels are shown below.

| Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | ||

| Close | i iː | y yː | u uː |

| Mid | e eː | ø øː | o oː |

| Open | æ æː | ɑ ɑː | |

The usual analysis is that Finnish has long and short vowels and consonants as distinct phonemes.[dubious ] However, long vowels may be analyzed as a vowel followed by a chroneme, or also, that sequences of identical vowels are pronounced as "diphthongs". The quality of long vowels mostly overlaps with the quality of short vowels, with the exception of u, which is centralized with respect to uu; long vowels do not morph into diphthongs. There are eighteen diphthongs; like vowels, diphthongs do not have significant allophony.

Consonantsedit

Finnish has a small consonant inventory, in which voicing is mostly not distinctive and fricatives are scarce. In the table below, consonants in parentheses are either found only in a few recent loans or are allophones of other phonemes.

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalv./ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ[note 1] | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t̪ | k | ʔ[note 2] | |

| voiced | (b) | d[note 3] | (ɡ) | |||

| Fricative | (f) | s | (ʃ) | h | ||

| Approximant | ʋ | l | j | |||

| Trill | r | |||||

- ^ The short velar nasal is an allophone of /n/ in /nk/, and the long velar nasal /ŋŋ/, written ng, is the equivalent of /nk/ under weakening consonant gradation (type of lenition) and thus occurs only medially, e.g. Helsinki – Helsingin kaupunki (city of Helsinki) /hɛlsiŋki – hɛlsiŋŋin/.

- ^ The glottal stop can only appear at word boundaries as a result of certain sandhi phenomena, and it is not indicated in spelling: e.g. /annaʔolla/ 'let it be', written anna olla. Moreover, this sound is not used in all dialects.

- ^ /d/ is the equivalent of /t/ under weakening consonant gradation, and thus in inherited vocabulary only occurs medially. Especially when spoken by older people, it is often more of an alveolar tap than a true voiced stop, and the dialectal realization varies widely; see the main article on Finnish phonology.

Almost all consonants have phonemic short and long (geminated) forms, although length is only contrastive in medial positions.

Consonant clusters are mostly absent from native Finnish words, except for a small set of two-consonant sequences in syllable codas, e.g. "rs" in karsta. However, as many recently adopted loanwords contain clusters, e.g. strutsi from Swedish struts, ('ostrich'), they have been integrated to the modern language in varying degrees.

Finnish is somewhat divergent from other Uralic languages in two respects: it has lost most of its fricatives and lost the distinction between palatalized and non-palatalized consonants. Finnish has only two fricatives in native words, /s/ and /h/. All other fricatives are recognized as foreign, of which Finnish speakers can usually reliably distinguish /f/ and /ʃ/. The alphabet includes "z", usually realized as the affricate ts, as in German.

While standard Finnish has lost palatalization, characteristic of Uralic languages, the eastern dialects and the Karelian language have redeveloped or retained it. For example, the Karelian word d'uuri dʲuːri, with a palatalized /dʲ/, is reflected by juuri in Finnish and Savo dialect vesj vesʲ is vesi in standard Finnish.

The phoneme /h/ can vary allophonically between ç~x~h~ɦ i.e. vihko 'ʋiçko̞, kahvi 'kɑxʋi, raha 'rɑɦɑ.

A feature of Finnic phonology is the development of labial and rounded vowels in non-initial syllables, as in the word tyttö. Proto-Uralic had only "a" and "i" and their vowel harmonic allophones in non-initial syllables; modern Finnish allows other vowels in non-initial syllables, although they are less common than "a", "ä" and "i".

Prosodyedit

Characteristic features of Finnish (common to some other Uralic languages) are vowel harmony and an agglutinative morphology; owing to the extensive use of the latter, words can be quite long.

The main stress is always on the first syllable, and is in average speech articulated by adding approximately 100 ms more length to the stressed vowel.[47] Stress does not cause any measurable modifications in vowel quality (very much unlike English). However, stress is not strong and words appear evenly stressed. In some cases, stress is so weak that the highest points of volume, pitch and other indicators of "articulation intensity" are not on the first syllable, although native speakers recognize the first syllable as being stressed.

Morphophonologyedit

Finnish has several morphophonological processes that require modification of the forms of words for daily speech. The most important processes are vowel harmony and consonant gradation.

Vowel harmony is a redundancy feature, which means that the feature ±back is uniform within a word, and so it is necessary to interpret it only once for a given word. It is meaning-distinguishing in the initial syllable, and suffixes follow; so, if the listener hears ±back in any part of the word, they can derive ±back for the initial syllable. For example, from the stem tuote ('product') one derives tuotteeseensa ('into his product'), where the final vowel becomes the back vowel "a" (rather than the front vowel "ä") because the initial syllable contains the back vowels "uo". This is especially notable because vowels "a" and "ä" are different, meaning-distinguishing phonemes, not interchangeable or allophonic. Finnish front vowels are not umlauts, though the graphemes ⟨ä⟩ and ⟨ö⟩ feature dieresis.

Consonant gradation is a partly nonproductive[48] lenition process for P, T and K in inherited vocabulary, with the oblique stem "weakened" from the nominative stem, or vice versa. For example, tarkka 'precise' has the oblique stem tarka-, as in tarkan 'of the precise'. There is also another gradation pattern, which is older, and causes simple elision of T and K in suffixes. However, it is very common since it is found in the partitive case marker: if V is a single vowel, V+ta → Va, e.g. *tarkka+ta → tarkkaa.

Grammaredit

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk