A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Worcester | |

|---|---|

| |

Worcester shown within Worcestershire | |

| Coordinates: 52°11′28″N 02°13′14″W / 52.19111°N 2.22056°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| Region | West Midlands |

| County | Worcestershire |

| Government | |

| • Local authority | Worcester City Council |

| • MPs | Robin Walker (Conservative) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12.85 sq mi (33.28 km2) |

| • Rank | 275th (of 296) |

| Population (2021 Census[1]) | |

| • Total | 103,872 |

| • Rank | 229th (of 296) |

| • Density | 8,100/sq mi (3,100/km2) |

| Ethnicity (2021) | |

| • Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2021) | |

| • Religion | List

|

| Time zone | UTC0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcodes | |

| Area code | 01905 |

| ONS code | 47UE (ONS) E07000237 (GSS) |

| OS grid reference | SO849548 |

| Website | worcester |

Worcester (/ˈwʊstər/ WUUST-ər) is a cathedral city in Worcestershire, England, of which it is the county town. It is 30 mi (48 km) south-west of Birmingham, 27 mi (43 km) north of Gloucester and 23 mi (37 km) north-east of Hereford. The population was 103,872 in the 2021 census.[3]

The River Severn flanks the western side of the city centre, overlooked by Worcester Cathedral. Worcester is the home of Royal Worcester Porcelain, Lea & Perrins (makers of traditional Worcestershire sauce), the University of Worcester, and Berrow's Worcester Journal, claimed as the world's oldest newspaper. The composer Edward Elgar (1857–1934) grew up in the city.

The Battle of Worcester in 1651 was the final battle of the English Civil War, during which Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army defeated King Charles II's Royalists.

History

Early history

The trade route past Worcester, later part of the Roman Ryknild Street, dates from Neolithic times. It commanded a ford crossing over the River Severn, which was tidal below Worcester, and fortified by the Britons about 400 BC.[4]

Charcoal from the Forest of Dean enabled Romans to operate pottery kilns and ironworks. They may also have built a small fort. While there is some evidence that the late Iron Age defensive ditches on the east bank may have been dug out during the first century AD, there is no other evidence to suggest that this was used as a fort by the Romans. Scatters of military equipment and coins found in the city centre from this early period may instead have been lost during the course of road building, or won by the local inhabitants in battle, rather than being left by a Roman military garrison. [5] There is no sign of municipal buildings to indicate an administrative role.[6]

In the 3rd century AD, Roman Worcester occupied a larger area than the subsequent medieval city, but silting caused the abandonment of Sidbury. Industrial production ceased and the settlement contracted to a defended position along the lines of the old British fort at the river terrace's southern end.[7]

Anglo-Saxon town

The form of the place name varied over time. At its settlement in the 7th century, by the Angles of Mercia, it was Weogorna. After centuries of warfare against the Vikings and Danelaw it had become a centre for the Anglo-Saxon army or here known as Weogorna ceastre (Worcester Camp). The Weorgoran were probably a sub-tribe of the larger kingdom of the Hwicce, which occupied present-day Worcestershire, Gloucestershire and western Wiltshire. In 680, Worcester was chosen as their fort over the larger Gloucester, and the royal court at Winchcombe as the episcopal see of a new bishopric, suggesting there was already an established and powerful Christian community.

Worcester became a centre of monastic learning and church power. Oswald of Worcester, appointed Bishop in 961, was an important reformer alongside the Archbishop of York. The last Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Worcester, St Wulfstan or Wulstan, was a reformer, who remained in office until he died in 1095.

The city also became a focus of violent tax resistance against the monarch Harthacnut (also King of Denmark) in 1041. The townspeople tried to defend themselves by occupying the Severn island of Bevere, two miles up river. After Harthacnut's men had sacked the city and set it alight, agreement was reached and the populace returned to rebuild.[8]

Medieval

Norman Conquest

The first Norman Sheriff of Worcestershire, Urse d'Abetot oversaw the construction of a new castle at Worcester,[9] although nothing now remains of the castle.[10] Worcester Castle was in place by 1069. Its outer bailey was built on land that had previously been the cemetery for the monks of the Worcester cathedral chapter.[11] The motte of the castle overlooked the river, just south of the cathedral.[12]

Early medieval

Worcester's growth and position as a market town for goods and produce rested on its river crossing and bridge and its position on the road network. The nearest Severn bridges in the 14th century were at Gloucester and Bridgnorth. The main road from London to mid-Wales ran through Worcester, then north-west to Kidderminster, Bridgnorth and Shrewsbury, and via Bromsgrove to Coventry and on to Derby. Southward it connected with Tewkesbury and Gloucester.[8]

Worcester was a centre of religious life. The several monasteries up to the dissolution included Greyfriars, Blackfriars, the Penitent Sisters, and the Benedictine Priory, now Worcester Cathedral.[13] Monastic houses provided hospital and educational services, including Worcester School.

The 12th-century town (then better defended) was attacked in 1139, 1150 and 1151 during the civil war between King Stephen and Empress Matilda, daughter of Henry I. The 1139 attack again resulted in a fire that destroyed part of the city, with citizens being held for ransom. Another fire in 1189 destroyed much of the city for the fourth time that century.[8]

Worcester received its first royal charter in 1189. In 1227 under a new charter allowed a guild of merchants was created, with a trading monopoly for those admitted.[8] Worcester's institutions grew more slowly than those of most county towns.[8]

Jewish persecution and expulsions

Worcester had a small Jewish population by the late 12th century. Jewish life probably centred round what is now Copenhagen Street.[14] The Diocese was hostile to the Jewish community. Peter of Blois was commissioned by a Bishop of Worcester, probably John of Coutances, to write an anti-Judaic treatise around 1190.[15] William de Blois as Bishop of Worcester imposed strict rules on Jews within the diocese in 1219.[16] As elsewhere in England, Jews had to wear square white badges, supposedly representing tabulae.[17] Blois wrote to Pope Gregory IX in 1229 to request further powers of enforcement.[18] In 1263 Worcester's Jewish residents were attacked by a baronial force under Robert Earl Ferrers and Henry de Montfort. Most were killed.[8] The Worcester massacre was part of a wider campaign by allies of Simon de Montfort at the start of the Second Barons' War. In January 1275, Jews still in Worcester were expelled to Hereford.[8]

Late medieval

Worcester elected its Member of Parliament at the Guildhall, by the loudest shout rather than the raising of hands. Members of Parliament had to own freehold property worth 40 shillings a year. Their wages were levied by the Constable.

The city council was organised by a system of co-option, with 24 members of the high chamber and 48 of the lower. Committees appointed two bailiffs and made financial decisions; the two chambers agreed the city's rules or ordinances.[8]

By late medieval times the population had reached 1,025 families, excluding the cathedral quarter, so that it probably stood under 10,000.[19] Worcester's suburbs extended beyond the limits of its walls[8]

Manufacture of cloth and allied trades was significant for the city.[8]

Craft guilds

Medieval and early modern Worcester developed a system of craft guilds to regulate who could work in a trade, lay down trade practices and training, and provide social support for members. The city's late medieval ordinances banned tilers from forming a guild and encouraged tilers to settle in Worcester to trade freely. Roofs of thatch and wooden chimneys were banned to reduce risks of fire.[8]

Early modern period

The Dissolution saw the Priory's status change, as it lost its Benedictine monks. As elsewhere, Worcester had to set up "public" schools to replace monastic education. This led to the establishment of King's School. Worcester School continued to teach. St Oswald's Hospital survived the dissolution, later providing almshouses;[20] the charity and its housing survives to the present day.

The city gained the right to elect a mayor, and was designated a county corporate in 1621, giving it autonomy from local government. Thereafter Worcester was governed by a mayor, recorder and six aldermen. Councillors were selected by co-option.[8]

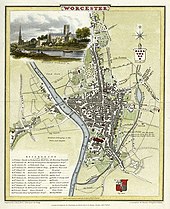

Worcester contained green spaces such as orchards and fields between its main streets, within the city wall, as appears on Speed's map of 1610. The walls were still more or less complete at the time, but suburbs had been established beyond them.

Civil war

Worcester equivocated, then sided with Parliament before the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642 but was swiftly occupied by the Royalists. Parliament briefly retook the city after the Battle of Powick Bridge of September 1642, and ransacked the cathedral, where stained glass was smashed and the organ destroyed, along with library books and monuments.[21]

The Parliamentary commander, the Earl of Essex was soon forced to withdraw, and the city spent the rest of the war under Royalist occupation. Worcester was a garrison town and had to sustain and billet a large number of Royalist troops. During the Royalist occupation, the suburbs were destroyed to make defence easier. High taxation was imposed, and many male residents pressed into the army.[22]

As Royalist power collapsed in May 1646, Worcester was placed under siege. Worcester had some 5,000 civilians and a Royalist garrison of about 1,500 men facing a New Model Army force of 2,500–5,000. The city surrendered on 23 July.[23]

In 1651 a Scottish army, 16,000 strong, marched south along the west coast in support of Charles II's attempt to regain the Crown. As the army approached, Worcester Council voted to surrender, fearing further violence and destruction. The Parliamentary garrison withdrew to Evesham in the face of the overwhelming numbers against them. The Scots were billeted in and around the city, joined by very limited local forces.[24]

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651. Charles II was easily defeated by Cromwell's forces of 30,000 men. Charles II returned to his headquarters in what is now known as King Charles House in the Cornmarket, before fleeing in disguise with help of one of his officers, Francis Talbot to Boscobel House in Shropshire, from where he eventually escaped to France. Worcester was then heavily looted by the Parliamentarian army. The city council estimated £80,000 of damage was done and subsequent debts were still not recovered in the 1670s.[25]

After the Restoration

After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Worcester cleverly used its location as the site of the final battles of the First Civil War (1646) and Third Civil War (1651) to mount an appeal for compensation from Charles II. Though not based on historical fact, it invented the epithet Fidelis Civitas (The Faithful City), since included in the city's coat of arms.[26][27]

During the 18th century Worcester experienced significant economic growth, and in 1748 Daniel Defoe could note that 'the inhabitants are generally esteemed rich, being full of business, occasioned chiefly by the clothing-trade'.[28] The Royal Worcester Porcelain Company was established at Warmstry Slip in 1751,[29] and from the later 18th century the city became a major centre for the glovemaking industry.[29]

The wealth of 18th- and 19th-century Worcester is reflected in the city's architecture, which has been described as 'one of the most impressive Georgian streetscapes in the Midlands'.[30] Many public buildings were built or rebuilt in this period, including the Grade I listed Worcester Guildhall,[30] the city bridge, and the Royal Infirmary.[31] Large stretches of the city walls were removed by 1796,[8] allowing for continued expansion along Foregate Street, The Tything, and Upper Tything,[29] and many townhouses were built or remodelled in brick.[30]

Worcester was a popular destination for wealthy visitors, who came to the annual Three Choirs Festival and horse races on Pitchcroft.[29][32] However, parts of the city suffered from significant poverty, and in 1794 a large workhouse was built on the edge of the city at Tallow Hill.[29]

Industrial revolution and Victorian era

Worcester in the late 18th and early 19th centuries was a major centre for glove-making, employing nearly half the glovers in England at its peak (over 30,000 people).[33] employed by 150 firms. At this time nearly half the glove makers in Britain could be found in Worcestershire. In the 19th century, the industry declined as import taxes on foreign competitors, mainly French, were much reduced.

Riots took place in 1831, in response to the defeat of the Reform Bill, reflecting discontent with the city administration and the lack of democratic representation.[8] Citizens petitioned the House of Lords for permission to build a County Hall.[34] Local government reform took place in 1835, which for the first time created election procedures for councillors, but also restricted the ability of the city to buy and sell property.[8] Political corruption, particularly bribing of voters, was endemic in Parliamentary elections, contributing to a string of Conservative victories even against a wider swing to the Liberals, and was investigated in the 1890s and by a Royal Commission in 1906.[35]

The British Medical Association (BMA) was founded in the Board Room of the old Worcester Royal Infirmary building in Castle Street in 1832.[36] Corn trading which had taken place in the Corn Market on the east side of the city moved to the new Corn Exchange in Angel Street in the mid-19th century.[37]

The Kays mail-order business was founded in Worcester in 1889 and operated from various premises in the city until 2007. It was then bought out by Reality, owner of the Grattan catalogue. The Kays warehouse was demolished in 2008 and replaced by housing.[38]

In 1815 the Worcester and Birmingham Canal opened. Railways reached Worcester in 1850, with Shrub Hill, initially only running to Birmingham. Foregate Street was opened in 1860. The WMR lines became part of the Great Western Railway after 1 August 1863. The railways also gave Worcester of jobs building passenger coaches and signalling. Alongside Worcester Shrub Hill station in Shrub Hill Road were the Worcester Engine Works. Their polychrome brick building was erected about 1864 and probably designed by Thomas Dickson. However, only 84 locomotives were built there and the works closed in 1871.[39] The chairman was Alexander Clunes Sheriff.[40]

In 1882 Worcester hosted the Worcestershire Exhibition with sections for fine arts, historical manuscripts and industrial items, receiving over 222,000 visitors.

20th century to present

The Foregate Street cast-iron railway bridge was remodelled by the Great Western Railway in 1908 with a decorative cast-iron exterior serving no structural purpose.[41] Rail reorganisation in 1922 saw the Midland Railway's routes from Shrub Hill absorbed into the London, Midland and Scottish Railway.

By the mid-20th century, only a few Worcester glove firms survived, as gloves became less fashionable and free trade enabled cheaper imports from the Far East. Nevertheless, at least three glove manufacturers survived into the late 20th century: Dent Allcroft, Fownes and Milore. In the 1940s, some Jewish refugees from Europe settled in Worcester. Emil Rich, a refugee from Germany, founded one of Worcester's last remaining glovemakers, Milore Glove Factory.[42] Queen Elizabeth II's coronation gloves were designed by Emil Rich and manufactured in the Worcester factory.[43][44]

Worcester was a centre for recruitment of soldiers to fight in the First World War, into the Worcestershire Regiment, based at Norton Barracks. The regiment took part in early battles in the war, most notably at the Battle of Gheluvelt in October 1914.[45] The Vicar of St Paul's, Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, became an army chaplain, later known as 'Woodbine Willy', as he brought cigarettes to soldiers during fighting and exposed himself to physical danger.[46]

The inter-war years saw rapid growth in engineering and machine-tool manufacturing firms such as James Archdale and H. W. Ward, castings for the motor industry from Worcester Windshields and Casements, valve design and manufacture from Alley & MacLellan, Sentinel Valve Works, mining machinery from Mining Engineering Company (MECO) – later part of Joy Mining Machinery – and open-top cans from Williamsons, although G. H. Williamson and Sons had become part of the Metal Box Co in 1930. Later the company became Carnaud Metal Box PLC.

During the Second World War, the city was chosen to be the seat of an evacuated government in case of mass German invasion. The War Cabinet, along with Winston Churchill and some 16,000 state workers, would have moved to Hindlip Hall (now part of the complex forming the Headquarters of West Mercia Police), 3 mi (4.8 km) north of Worcester. The former RAF station RAF Worcester was located north-east of Worcester.[47]

A fuel-storage depot was built for the government in 1941–42 by Shell-Mex and BP (later operated by Texaco) on the eastern bank of the River Severn, about a mile south of Worcester. It was at one time used as a civil reserve storing gas oil and then aviation kerosene for USAFE. It closed in the early 1990s.[48] Worcester Porcelain operated in Worcester until 2009, when the factory closed due to the recession.

In the 1950s and 1960s large areas of the medieval centre of Worcester were demolished and rebuilt. This was condemned by many such as Nikolaus Pevsner who described it as a "totally incomprehensible... act of self-mutilation".[49] There is however still a significant area of medieval Worcester remaining, examples of which can be seen along City Walls Road, Friar Street and New Street.

Governance

There are two tiers of local government covering Worcester, at district (city) and county level: Worcester City Council and Worcestershire County Council. There are two civil parishes within the city at Warndon and St Peter the Great County, which form a third tier of local government in those areas; the rest of the city is an unparished area. Worcester forms one of the six local government districts within the county.[50]

Worcester City Council is based at Worcester Guildhall on the High Street in the city centre. Worcestershire County Council also has its headquarters in Worcester, being based at County Hall in Spetchley Road, on the eastern outskirts of the city.

Worcester was an ancient borough which had held city status from time immemorial. When elected county councils were established in 1889, the city was considered large enough to run its own county-level services and so it became a county borough, independent from the surrounding Worcestershire County Council.[51]

Worcester was reformed to become a non-metropolitan district in 1974 under the Local Government Act 1972. The city had its territory enlarged, gaining the parishes of Warndon and St Peter the Great County, and it was transferred to the short-lived county of Hereford and Worcester.[52] Hereford and Worcester was abolished in 1998, since when a re-established Worcestershire County Council has been the upper-tier authority for Worcester.[53]

Worcester's one Member of Parliament (MP) is Robin Walker of the Conservative Party, who has represented the Worcester constituency since the May 2010 general election.[54]

Coat of arms

The city of Worcester is unusual among English cities in having an arms of alliance as the main part of its coat of arms. The shield on the dexter side is the "ancient" arms: Quarterly sable and gules, a castle triple-towered argent. First recorded in 1569 but probably older, there is little doubt that it refers to Worcester Castle, now vanished. The shield on the sinister side is the "modern" arms: Argent, a fess between three pears sable. Despite its name, the modern arms goes back to 1634. It is said to represent a visit of Queen Elizabeth I to the city in 1575, when according to folklore, she saw a tree with black pears on Foregate and was so impressed with it that she allowed Worcester to have pears on its coat of arms. The city has used several mottos: one is Floreat semper fidelis civitas, Latin for "Let the faithful city ever flourish", while the one currently used is Civitas in bello et pace fidelis (A city faithful in peace and war). Both refer to Worcester's support for Royalists in the English Civil War.[55]

-

The "ancient" arms of the city on the railway bridge near Foregate Street station

-

The "modern" arms of the city on the railway bridge near Foregate Street station

-

The coat of arms as shown on the entrance gate to Cripplegate Park

-

The coat of arms as shown in the Guildhall, with the "modern" placed over the "ancient"

Geography

The district is bounded by the districts of Malvern Hills to the west, and Wychavon to the east. The population of the local government district in 2021 was 103,837.[1] The built up area extends slightly beyond the city boundaries in places and had a population in 2021 of 105,465.[56]

Notable suburbs include Barbourne, Blackpole, Cherry Orchard, Claines, Diglis, Dines Green, Henwick, Northwick, Red Hill, Ronkswood, St Peter the Great (also known as St Peter's), Tolladine, Warndon and Warndon Villages. Most of Worcester is on the eastern side of the River Severn. However, Henwick, Lower Wick, St John's and Dines Green are on the western side.

Climate

Worcester enjoys a temperate climate with generally warm summers and mild winters. However, it can experience more extreme weather and flooding is often a problem.[57] In 1670, the River Severn burst its banks in the worst flood ever seen by the city. The closest flood height to the Flood of 1670 was when torrential rains caused the Severn to flood in July 2007, which is recorded in the Diglis Basin.[58] This recurred in 2014.[59]

During the winters of 2009–2010 and 2010–2011, the city underwent long periods of sub-freezing temperatures and heavy snowfalls. In December 2010 the temperature dropped to −19.5 °C (−3.1 °F) in nearby Pershore.[60] The Severn and the River Teme partly froze over in Worcester during this cold period. By contrast, Worcester recorded a temperature 36.6 °C (97.9 °F) on 2 August 1990.[61] Between 1990 and 2003, weather data for the area was collected at Barbourne, Worcester. Since the closure of this weather station, the nearest is located at Pershore.[62]