A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

India | |

|---|---|

| 1858–1947 | |

| Anthem: "God Save the King/Queen" | |

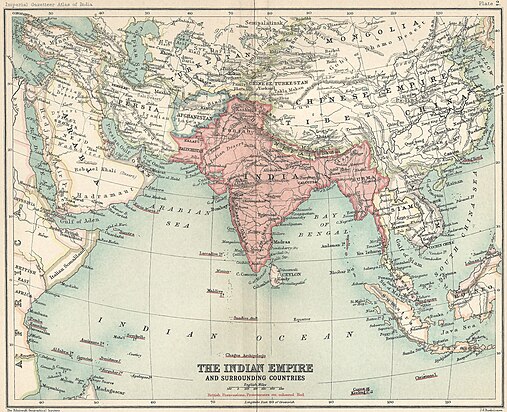

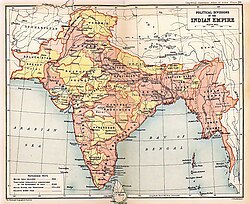

Political subdivisions of the British Raj in 1909. British India is shown in two shades of pink; Sikkim, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Princely states are shown in yellow. | |

The British Raj in relation to the British Empire in 1909 | |

| Status | Imperial political structure (comprising British India[a] and the Princely States[b][1] |

| Capital | Calcutta[2][c] (1858–1911) New Delhi (1911/1931[d]–1947) |

| Official languages | |

| Demonym(s) | Indians, British Indians |

| Government | British Colonial Government |

| Queen/Queen-Empress/King-Emperor | |

• 1858–1876 (Queen); 1876–1901 (Queen-Empress) | Victoria |

• 1901–1910 | Edward VII |

• 1910–1936 | George V |

• 1936 | Edward VIII |

• 1936–1947 (last) | George VI |

| Viceroy | |

• 1858–1862 (first) | Charles Canning |

• 1947 (last) | Louis Mountbatten |

| Secretary of State | |

• 1858–1859 (first) | Edward Stanley |

• 1947 (last) | William Hare |

| Legislature | Imperial Legislative Council |

| History | |

| 10 May 1857 | |

| 2 August 1858 | |

| 18 July 1947 | |

| took effect Midnight, 14–15 August 1947 | |

| Currency | Indian rupee |

| |

The British Raj (/rɑːdʒ/ RAHJ; from Hindi rāj, 'kingdom', 'realm', 'state', or 'empire')[11][a] was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;[13] it is also called Crown rule in India,[14] or Direct rule in India,[15] and lasted from 1858 to 1947.[16] The region under British control was commonly called India in contemporaneous usage and included areas directly administered by the United Kingdom, which were collectively called British India, and areas ruled by indigenous rulers, but under British paramountcy, called the princely states. The region was sometimes called the Indian Empire, though not officially.[17]

As India, it was a founding member of the League of Nations, a participating state in the Summer Olympics in 1900, 1920, 1928, 1932, and 1936, and a founding member of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945.[18]

This system of governance was instituted on 28 June 1858, when, after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the rule of the East India Company was transferred to the Crown in the person of Queen Victoria[19] (who, in 1876, was proclaimed Empress of India). It lasted until 1947, when the British Raj was partitioned into two sovereign dominion states: the Union of India (later the Republic of India) and Pakistan (later the Islamic Republic of Pakistan). Later, the People's Republic of Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan. At the inception of the Raj in 1858, Lower Burma was already a part of British India; Upper Burma was added in 1886, and the resulting union, Burma, was administered as an autonomous province until 1937, when it became a separate British colony, gaining its own independence in 1948. It was renamed Myanmar in 1989. The Chief Commissioner's Province of Aden was also part of British India at the inception of the British Raj, and became a separate colony known as Aden Colony in 1937 as well.

Geographical extent

The British Raj extended over almost all present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, except for small holdings by other European nations such as Goa and Pondicherry.[20] This area is very diverse, containing the Himalayan mountains, fertile floodplains, the Indo-Gangetic Plain, a long coastline, tropical dry forests, arid uplands, and the Thar Desert.[21] In addition, at various times, it included Aden (from 1858 to 1937),[22] Lower Burma (from 1858 to 1937), Upper Burma (from 1886 to 1937), British Somaliland (briefly from 1884 to 1898), and the Straits Settlements (briefly from 1858 to 1867). Burma was separated from India and directly administered by the British Crown from 1937 until its independence in 1948. The Trucial States of the Persian Gulf and the other states under the Persian Gulf Residency were theoretically princely states as well as presidencies and provinces of British India until 1947 and used the rupee as their unit of currency.[23]

Among other countries in the region, Ceylon, which was referred to coastal regions and northern part of the island at that time (now Sri Lanka) was ceded to Britain in 1802 under the Treaty of Amiens. These coastal regions were temporarily administered under Madras Presidency between 1793 and 1798,[24] but for later periods the British governors reported to London, and it was not part of the Raj. The kingdoms of Nepal and Bhutan, having fought wars with the British, subsequently signed treaties with them and were recognised by the British as independent states.[25][26] The Kingdom of Sikkim was established as a princely state after the Anglo-Sikkimese Treaty of 1861; however, the issue of sovereignty was left undefined.[27] The Maldive Islands were a British protectorate from 1887 to 1965, but not part of British India.[28]

-

The British Raj and surrounding countries are shown in 1909.

History

1858–1868: rebellion aftermath, critiques, and responses

-

Lakshmibai, Rani of Jhansi, one of the principal leaders of the Great Uprising of 1857, who had lost her kingdom by the Doctrine of lapse

-

The proclamation to the "Princes, Chiefs, and People of India", issued by Queen Victoria on 1 November 1858

-

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan founder of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, wrote one of the early critiques, The Causes of the Indian Mutiny.

-

An 1887 souvenir portrait of Queen Victoria as Empress of India, 30 years after the Great Uprising

Although the Indian Rebellion of 1857 had shaken the British enterprise in India, it had not derailed it. Until 1857, the British, especially under Lord Dalhousie, had been hurriedly building an India which they envisaged to be on par with Britain itself in the quality and strength of its economic and social institutions. After the rebellion, they became more circumspect. Much thought was devoted to the causes of the rebellion and three main lessons were drawn. First, at a practical level, it was felt that there needed to be more communication and camaraderie between the British and Indians—not just between British army officers and their Indian staff but in civilian life as well.[29] The Indian army was completely reorganised: units composed of the Muslims and Brahmins of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, who had formed the core of the rebellion, were disbanded. New regiments, like the Sikhs and Baluchis, composed of Indians who, in British estimation, had demonstrated steadfastness, were formed. From then on, the Indian army was to remain unchanged in its organisation until 1947.[30] The 1861 Census had revealed that the English population in India was 125,945. Of these only about 41,862 were civilians as compared with about 84,083 European officers and men of the Army.[31] In 1880, the standing Indian Army consisted of 66,000 British soldiers, 130,000 Natives, and 350,000 soldiers in the princely armies.[32]

Second, it was also felt that both the princes and the large land-holders, by not joining the rebellion, had proved to be, in Lord Canning's words, "breakwaters in a storm".[29] They too were rewarded in the new British Raj by being integrated into the British-Indian political system and having their territories guaranteed.[33] At the same time, it was felt that the peasants, for whose benefit the large land reforms of the United Provinces had been undertaken, had shown disloyalty, by, in many cases, fighting for their former landlords against the British. Consequently, no more land reforms were implemented for the next 90 years: Bengal and Bihar were to remain the realms of large land holdings (unlike the Punjab and Uttar Pradesh).[34]

Third, the British felt disenchanted with Indian reaction to social change. Until the rebellion, they had enthusiastically pushed through social reform, like the ban on sati by Lord William Bentinck.[35] It was now felt that traditions and customs in India were too strong and too rigid to be changed easily; consequently, no more British social interventions were made, especially in matters dealing with religion,[36] even when the British felt very strongly about the issue (as in the instance of the remarriage of Hindu child widows).[37] This was exemplified further in Queen Victoria's Proclamation released immediately after the rebellion. The proclamation stated that 'We disclaim alike our Right and Desire to impose Our Convictions on any of Our Subjects';[38] demonstrating official British commitment to abstaining from social intervention in India.

1858–1880: railways, canals, Famine Code

-

The 1909 map of Indian Railways, the fourth largest in the world. Railway construction began in 1853.

-

Stereographic image of Victoria Terminus, Bombay, completed in 1888

-

The Agra canal (c. 1873), a year from completion, was closed to navigation in 1904 to increase irrigation during a famine.

-

Lord Ripon, the Liberal Viceroy of India, who instituted the Famine Code. 1880.

In the second half of the 19th century, both the direct administration of India by the British crown and the technological change ushered in by the industrial revolution, had the effect of closely intertwining the economies of India and Great Britain.[39] In fact many of the major changes in transport and communications (that are typically associated with Crown Rule of India) had already begun before the Mutiny. Since Dalhousie had embraced the technological change then rampant in Great Britain, India too saw the rapid development of all those technologies. Railways, roads, canals, and bridges were rapidly built in India, and telegraph links were equally rapidly established so that raw materials, such as cotton, from India's hinterland, could be transported more efficiently to ports, such as Bombay, for subsequent export to England.[40] Likewise, finished goods from England, were transported back for sale in the burgeoning Indian markets.[41] Unlike Britain, where the market risks for the infrastructure development were borne by private investors, in India, it was the taxpayers—primarily farmers and farm-labourers—who endured the risks, which, in the end, amounted to £50 million.[42] Despite these costs, very little skilled employment was created for Indians. By 1920, with the fourth largest railway network in the world and a history of 60 years of its construction, only ten per cent of the "superior posts" in the Indian Railways were held by Indians.[43]

The rush of technology was also changing the agricultural economy in India: by the last decade of the 19th century, a large fraction of some raw materials—not only cotton, but also some food-grains—were being exported to faraway markets.[44] Many small farmers, dependent on the whims of those markets, lost land, animals, and equipment to money-lenders.[44] The latter half of the 19th century also saw an increase in the number of large-scale famines in India. Although famines were not new to the subcontinent, these were particularly severe, with tens of millions dying,[citation needed] and with many critics, both British and Indian, laying the blame at the doorsteps of the lumbering colonial administrations.[44] There were also salutary effects: commercial cropping, especially in the newly canalled Punjab, led to increased food production for internal consumption.[45] The railway network provided critical famine relief,[46] notably reduced the cost of moving goods,[46] and helped nascent Indian-owned industry.[45] After, the Great Famine of 1876–1878, The Indian Famine Commission report was issued in 1880, and the Indian Famine Codes, the earliest famine scales and programmes for famine prevention, were instituted.[47] In one form or other, they would be implemented worldwide by the United Nations and the Food and Agricultural Organisation well into the 1970s.[citation needed]

1880s–1890s: middle class, Indian National Congress

-

Allan Octavian Hume (1829–1912), who proposed the idea of the Indian National Congress in a letter to graduates of Calcutta University

-

Congress, Bombay, December 28, 1885. Third row (middle) (l. to r.) Dadabhai Naoroji, Hume, W. C. Bonerjee, and Pherozeshah Mehta.

-

Poverty and the Un-British Rule in India, 1901, by Naoroji, Member, British Parliament (1892–1895), and Congress president (1886, 1893, 1906)

-

Mehta, lawyer, businessman, and president of the sixth session of the Indian National Congress in 1890

By 1880, a new middle class had arisen in India and spread thinly across the country. Moreover, there was a growing solidarity among its members, created by the "joint stimuli of encouragement and irritation".[48] The encouragement felt by this class came from its success in education and its ability to avail itself of the benefits of that education such as employment in the Indian Civil Service. It came too from Queen Victoria's proclamation of 1858 in which she had declared, "We hold ourselves bound to the natives of our Indian territories by the same obligation of duty which bind us to all our other subjects."[49] Indians were especially encouraged when Canada was granted dominion status in 1867 and established an autonomous democratic constitution.[49] Lastly, the encouragement came from the work of contemporaneous Oriental scholars like Monier Monier-Williams and Max Müller, who in their works had been presenting ancient India as a great civilisation. Irritation, on the other hand, came not just from incidents of racial discrimination at the hands of the British in India, but also from governmental actions like the use of Indian troops in imperial campaigns (e.g. in the Second Anglo-Afghan War) and the attempts to control the vernacular press (e.g. in the Vernacular Press Act of 1878).[50]

It was, however, Viceroy Lord Ripon's partial reversal of the Ilbert Bill (1883), a legislative measure that had proposed putting Indian judges in the Bengal Presidency on equal footing with British ones, that transformed the discontent into political action.[51] On 28 December 1885, professionals and intellectuals from this middle-class — many educated at the new British-founded universities in Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, and familiar with the ideas of British political philosophers, especially the utilitarians assembled in Bombay — founded the Indian National Congress. The 70 men elected Womesh Chunder Bonerjee as the first president. The membership comprised a westernised elite, and no effort was made at this time to broaden the base.[citation needed]

During its first 20 years, the Congress primarily debated British policy toward India. Its debates created a new Indian outlook that held Great Britain responsible for draining India of its wealth. Britain did this, the nationalists claimed, by unfair trade, by the restraint on indigenous Indian industry, and by the use of Indian taxes to pay the high salaries of the British civil servants in India.[52]

Thomas Baring served as Viceroy of India 1872–1876. Baring's major accomplishments came as an energetic reformer who was dedicated to upgrading the quality of government in the British Raj. He began large scale famine relief, reduced taxes, and overcame bureaucratic obstacles in an effort to reduce both starvation and widespread social unrest. Although appointed by a Liberal government, his policies were much the same as viceroys appointed by Conservative governments.[53]

Social reform was in the air by the 1880s. For example, Pandita Ramabai, poet, Sanskrit scholar, and a champion of the emancipation of Indian women, took up the cause of widow remarriage, especially of Brahmin widows, later converted to Christianity.[54] By 1900 reform movements had taken root within the Indian National Congress. Congress member Gopal Krishna Gokhale founded the Servants of India Society, which lobbied for legislative reform (for example, for a law to permit the remarriage of Hindu child widows), and whose members took vows of poverty, and worked among the untouchable community.[55]

By 1905, a deep gulf opened between the moderates, led by Gokhale, who downplayed public agitation, and the new "extremists" who not only advocated agitation, but also regarded the pursuit of social reform as a distraction from nationalism. Prominent among the extremists was Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who attempted to mobilise Indians by appealing to an explicitly Hindu political identity, displayed, for example, in the annual public Ganapati festivals that he inaugurated in western India.[56]

1905–1911: Partition of Bengal, Swadeshi, violence

-

Congress moderate Sir Surendranath Banerjee led the opposition with the Swadeshi movement.

-

Tamil magazine, Vijaya, 1909, showing "Mother India" with her progeny and the slogan "Vande Mataram"

The viceroy, Lord Curzon (1899–1905), was unusually energetic in pursuit of efficiency and reform.[57] His agenda included the creation of the North-West Frontier Province; small changes in the civil services; speeding up the operations of the secretariat; setting up a gold standard to ensure a stable currency; creation of a Railway Board; irrigation reform; reduction of peasant debts; lowering the cost of telegrams; archaeological research and the preservation of antiquities; improvements in the universities; police reforms; upgrading the roles of the Native States; a new Commerce and Industry Department; promotion of industry; revised land revenue policies; lowering taxes; setting up agricultural banks; creating an Agricultural Department; sponsoring agricultural research; establishing an Imperial Library; creating an Imperial Cadet Corps; new famine codes; and, indeed, reducing the smoke nuisance in Calcutta.[58]

Trouble emerged for Curzon when he divided the largest administrative subdivision in British India, the Bengal Province, into the Muslim-majority province of Eastern Bengal and Assam and the Hindu-majority province of West Bengal (present-day Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha). Curzon's act, the Partition of Bengal, had been contemplated by various colonial administrations since the time of Lord William Bentinck, but was never acted upon. Though some considered it administratively felicitous, it was communally charged. It sowed the seeds of division among Indians in Bengal, transforming nationalist politics as nothing else before it. The Hindu elite of Bengal, among them many who owned land in East Bengal that was leased out to Muslim peasants, protested fervidly.[59]

Following the Partition of Bengal, which was a strategy set out by Lord Curzon to weaken the nationalist movement, Tilak encouraged the Swadeshi movement and the Boycott movement.[60] The movement consisted of the boycott of foreign goods and also the social boycott of any Indian who used foreign goods. The Swadeshi movement consisted of the usage of natively produced goods. Once foreign goods were boycotted, there was a gap which had to be filled by the production of those goods in India itself. Bal Gangadhar Tilak said that the Swadeshi and Boycott movements are two sides of the same coin. The large Bengali Hindu middle-class (the Bhadralok), upset at the prospect of Bengalis being outnumbered in the new Bengal province by Biharis and Oriyas, felt that Curzon's act was punishment for their political assertiveness. The pervasive protests against Curzon's decision took the form predominantly of the Swadeshi ("buy Indian") campaign led by two-time Congress president, Surendranath Banerjee, and involved boycott of British goods.[61]

The rallying cry for both types of protest was the slogan Bande Mataram ("Hail to the Mother"), which invoked a mother goddess, who stood variously for Bengal, India, and the Hindu goddess Kali. Sri Aurobindo never went beyond the law when he edited the Bande Mataram magazine; it preached independence but within the bounds of peace as far as possible. Its goal was Passive Resistance.[62] The unrest spread from Calcutta to the surrounding regions of Bengal when students returned home to their villages and towns. Some joined local political youth clubs emerging in Bengal at the time, some engaged in robberies to fund arms, and even attempted to take the lives of Raj officials. However, the conspiracies generally failed in the face of intense police work.[63] The Swadeshi boycott movement cut imports of British textiles by 25%. The swadeshi cloth, although more expensive and somewhat less comfortable than its Lancashire competitor, was worn as a mark of national pride by people all over India.[64]

1870s–1906: Muslim social movements, Muslim League

-

Lord Minto, the viceroy who replaced Curzon in 1906. The Minto-Morley Reforms of 1909 allowed separate Muslim electorates.

-

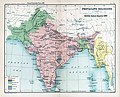

1909 Prevailing Religions, map of the British Indian Empire, 1909, showing the majority religions based on the Census of 1901

-

Hakim Ajmal Khan, a founder of the Muslim League, was to also become the president of the Indian National Congress in 1921.

The overwhelming, but predominantly Hindu, protest against the partition of Bengal and the fear in its wake of reforms favouring the Hindu majority, led the Muslim elite in India to meet with the new viceroy, Lord Minto in 1906 and to ask for separate electorates for Muslims.[41] In conjunction, they demanded proportional legislative representation reflecting both their status as former rulers and their record of cooperating with the British. This led,[citation needed] in December 1906, to the founding of the All-India Muslim League in Dacca. Although Curzon, by now, had resigned his position over a dispute with his military chief Lord Kitchener and returned to England, the League was in favour of his partition plan.[65] The Muslim elite's position, which was reflected in the League's position, had crystallized gradually over the previous three decades, beginning with the revelations of the Census of British India in 1871,[citation needed] which had for the first time estimated the populations in regions of the Muslim majority[65] (for his part, Curzon's desire to court the Muslims of East Bengal had arisen from British anxieties ever since the 1871 census—and in light of the history of Muslims fighting them in the 1857 Mutiny and the Second Anglo-Afghan War—about Indian Muslims rebelling against the Crown).[citation needed] In the three decades since, Muslim leaders across northern India had intermittently experienced public animosity from some of the new Hindu political and social groups.[65] The Arya Samaj, for example, had not only supported Cow Protection Societies in their agitation,[66] but also—distraught at the 1871 Census's Muslim numbers—organized "reconversion" events for the purpose of welcoming Muslims back to the Hindu fold.[65] In 1905, when Tilak and Lajpat Rai attempted to rise to leadership positions in the Congress, and the Congress itself rallied around the symbolism of Kali, Muslim fears increased.[67] It was not lost on many Muslims, for example, that the rallying cry, "Bande Mataram", had first appeared in the novel Anand Math in which Hindus had battled their Muslim oppressors.[67] Lastly, the Muslim elite, and among it Dacca Nawab, Khwaja Salimullah, who hosted the League's first meeting in his mansion in Shahbag, was aware that a new province with a Muslim majority would directly benefit Muslims aspiring to political power.[67]

The first steps were taken toward self-government in British India in the late 19th century with the appointment of Indian counsellors to advise the British viceroy and the establishment of provincial councils with Indian members; the British subsequently widened participation in legislative councils with the Indian Councils Act of 1892. Municipal Corporations and District Boards were created for local administration; they included elected Indian members.

The Indian Councils Act 1909, known as the Morley-Minto Reforms (John Morley was the secretary of state for India, and Minto was viceroy)—gave Indians limited roles in the central and provincial legislatures. Upper-class Indians, rich landowners and businessmen were favoured. The Muslim community was made a separate electorate and granted double representation. The goals were quite conservative but they did advance the elective principle.[68]

The partition of Bengal was rescinded in 1911 and announced at the Delhi Durbar at which King George V came in person and was crowned Emperor of India. He announced the capital would be moved from Calcutta to Delhi. This period saw an increase in the activities of revolutionary groups, which included Bengal's Anushilan Samiti and the Punjab's Ghadar Party. However, the British authorities were able to crush violent rebels swiftly, partly because the mainstream of educated Indian politicians opposed violent revolution.[69]

1914–1918: First World War, Lucknow Pact, Home Rule leagues

-

Khudadad Khan, the first Indian to be awarded the Victoria Cross, hailed from Chakwal District, Punjab (present-day Pakistan).

-

Indian medical orderlies with the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force in Mesopotamia during World War I

-

Annie Besant shown with the Theosophists in Adyar, Madras in 1912 four years before she founded an Indian Home Rule League[b]

-

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, seated, third from the left, supported the Lucknow Pact in 1916, ending the Muslim League-Congress rift.

The First World War would prove to be a watershed in the imperial relationship between Britain and India. Shortly before the outbreak of war, the Government of India had indicated that they could furnish two divisions plus a cavalry brigade, with a further division in case of emergency.[70] Some 1.4 million Indian and British soldiers of the British Indian Army took part in the war, primarily in Iraq and the Middle East. Their participation had a wider cultural fallout as news spread of how bravely soldiers fought and died alongside British soldiers, as well as soldiers from dominions like Canada and Australia.[71] India's international profile rose during the 1920s, as it became a founding member of the League of Nations in 1920 and participated, under the name "Les Indes Anglaises" (British India), in the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp.[72] Back in India, especially among the leaders of the Indian National Congress, the war led to calls for greater self-government for Indians.[71]

At the onset of World War I, the reassignment of most of the British army in India to Europe and Mesopotamia, had led the previous viceroy, Lord Harding, to worry about the "risks involved in denuding India of troops".[71] Revolutionary violence had already been a concern in British India; consequently, in 1915, to strengthen its powers during what it saw was a time of increased vulnerability, the Government of India passed the Defence of India Act 1915, which allowed it to intern politically dangerous dissidents without due process, and added to the power it already had—under the 1910 Press Act—both to imprison journalists without trial and to censor the press.[73] It was under the Defence of India act that the Ali brothers were imprisoned in 1916, and Annie Besant, a European woman, and ordinarily more problematic to imprison, was arrested in 1917.[73] Now, as constitutional reform began to be discussed in earnest, the British began to consider how new moderate Indians could be brought into the fold of constitutional politics and, simultaneously, how the hand of established constitutionalists could be strengthened. However, since the Government of India wanted to ensure against any sabotage of the reform process by extremists, and since its reform plan was devised during a time when extremist violence had ebbed as a result of increased governmental control, it also began to consider how some of its wartime powers could be extended into peacetime.[73]

After the 1906 split between the moderates and the extremists in the Indian National Congress, organised political activity by the Congress had remained fragmented until 1914, when Bal Gangadhar Tilak was released from prison and began to sound out other Congress leaders about possible reunification. That, however, had to wait until the demise of Tilak's principal moderate opponents, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Pherozeshah Mehta, in 1915, whereupon an agreement was reached for Tilak's ousted group to re-enter the Congress.[71] In the 1916 Lucknow session of the Congress, Tilak's supporters were able to push through a more radical resolution which asked for the British to declare that it was their "aim and intention ... to confer self-government on India at an early date".[71] Soon, other such rumblings began to appear in public pronouncements: in 1917, in the Imperial Legislative Council, Madan Mohan Malaviya spoke of the expectations the war had generated in India, "I venture to say that the war has put the clock ... fifty years forward ... (The) reforms after the war will have to be such, ... as will satisfy the aspirations of her (India's) people to take their legitimate part in the administration of their own country."[71]

The 1916 Lucknow Session of the Congress was also the venue of an unanticipated mutual effort by the Congress and the Muslim League, the occasion for which was provided by the wartime partnership between Germany and Turkey. Since the Turkish Sultan, or Khalifah, had also sporadically claimed guardianship of the Islamic holy sites of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem, and since the British and their allies were now in conflict with Turkey, doubts began to increase among some Indian Muslims about the "religious neutrality" of the British, doubts that had already surfaced as a result of the reunification of Bengal in 1911, a decision that was seen as ill-disposed to Muslims.[74] In the Lucknow Pact, the League joined the Congress in the proposal for greater self-government that was campaigned for by Tilak and his supporters; in return, the Congress accepted separate electorates for Muslims in the provincial legislatures as well as the Imperial Legislative Council. In 1916, the Muslim League had anywhere between 500 and 800 members and did not yet have the wider following among Indian Muslims that it enjoyed in later years; in the League itself, the pact did not have unanimous backing, having largely been negotiated by a group of "Young Party" Muslims from the United Provinces (UP), most prominently, two brothers Mohammad and Shaukat Ali, who had embraced the Pan-Islamic cause;[74] however, it did have the support of a young lawyer from Bombay, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who was later to rise to leadership roles in both the League and the Indian independence movement. In later years, as the full ramifications of the pact unfolded, it was seen as benefiting the Muslim minority élites of provinces like UP and Bihar more than the Muslim majorities of Punjab and Bengal; nonetheless, at the time, the "Lucknow Pact" was an important milestone in nationalistic agitation and was seen as such by the British.[74]

During 1916, two Home Rule Leagues were founded within the Indian National Congress by Tilak and Annie Besant, respectively, to promote Home Rule among Indians, and also to elevate the stature of the founders within the Congress itself.[75] Besant, for her part, was also keen to demonstrate the superiority of this new form of organised agitation, which had achieved some success in the Irish home rule movement, over the political violence that had intermittently plagued the subcontinent during the years 1907–1914.[75] The two Leagues focused their attention on complementary geographical regions: Tilak's in western India, in the southern Bombay presidency, and Besant's in the rest of the country, but especially in the Madras Presidency and in regions like Sind and Gujarat that had hitherto been considered politically dormant by the Congress.[75] Both leagues rapidly acquired new members—approximately thirty thousand each in a little over a year—and began to publish inexpensive newspapers. Their propaganda also turned to posters, pamphlets, and political-religious songs, and later to mass meetings, which not only attracted greater numbers than in earlier Congress sessions, but also entirely new social groups such as non-Brahmins, traders, farmers, students, and lower-level government workers.[75] Although they did not achieve the magnitude or character of a nationwide mass movement, the Home Rule leagues both deepened and widened organised political agitation for self-rule in India. The British authorities reacted by imposing restrictions on the Leagues, including shutting out students from meetings and banning the two leaders from travelling to certain provinces.[75]

1915–1918: return of Gandhi

The year 1915 also saw the return of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to India. Already known in India as a result of his civil liberties protests on behalf of the Indians in South Africa, Gandhi followed the advice of his mentor Gopal Krishna Gokhale and chose not to make any public pronouncements during the first year of his return, but instead spent the year travelling, observing the country at first hand, and writing.[76] Earlier, during his South Africa sojourn, Gandhi, a lawyer by profession, had represented an Indian community, which, although small, was sufficiently diverse to be a microcosm of India itself. In tackling the challenge of holding this community together and simultaneously confronting the colonial authority, he had created a technique of non-violent resistance, which he labelled Satyagraha (or Striving for Truth).[77] For Gandhi, Satyagraha was different from "passive resistance", by then a familiar technique of social protest, which he regarded as a practical strategy adopted by the weak in the face of superior force; Satyagraha, on the other hand, was for him the "last resort of those strong enough in their commitment to truth to undergo suffering in its cause".[77] Ahimsa or "non-violence", which formed the underpinning of Satyagraha, came to represent the twin pillar, with Truth, of Gandhi's unorthodox religious outlook on life.[77] During the years 1907–1914, Gandhi tested the technique of Satyagraha in a number of protests on behalf of the Indian community in South Africa against the unjust racial laws.[77]

Also, during his time in South Africa, in his essay, Hind Swaraj, (1909), Gandhi formulated his vision of Swaraj, or "self-rule" for India based on three vital ingredients: solidarity between Indians of different faiths, but most of all between Hindus and Muslims; the removal of untouchability from Indian society; and the exercise of swadeshi—the boycott of manufactured foreign goods and the revival of Indian cottage industry.[76] The first two, he felt, were essential for India to be an egalitarian and tolerant society, one befitting the principles of Truth and Ahimsa, while the last, by making Indians more self-reliant, would break the cycle of dependence that was perpetuating not only the direction and tenor of the British rule in India, but also the British commitment to it.[76] At least until 1920, the British presence itself was not a stumbling block in Gandhi's conception of swaraj; rather, it was the inability of Indians to create a modern society.[76]

Gandhi made his political debut in India in 1917 in Champaran district in Bihar, near the Nepal border, where he was invited by a group of disgruntled tenant farmers who, for many years, had been forced into planting indigo (for dyes) on a portion of their land and then selling it at below-market prices to the British planters who had leased them the land.[78] Upon his arrival in the district, Gandhi was joined by other agitators, including a young Congress leader, Rajendra Prasad, from Bihar, who would become a loyal supporter of Gandhi and go on to play a prominent role in the Indian independence movement. When Gandhi was ordered to leave by the local British authorities, he refused on moral grounds, setting up his refusal as a form of individual Satyagraha. Soon, under pressure from the Viceroy in Delhi who was anxious to maintain domestic peace during wartime, the provincial government rescinded Gandhi's expulsion order, and later agreed to an official enquiry into the case. Although the British planters eventually gave in, they were not won over to the farmers' cause, and thereby did not produce the optimal outcome of a Satyagraha that Gandhi had hoped for; similarly, the farmers themselves, although pleased at the resolution, responded less than enthusiastically to the concurrent projects of rural empowerment and education that Gandhi had inaugurated in keeping with his ideal of swaraj. The following year Gandhi launched two more Satyagrahas—both in his native Gujarat—one in the rural Kaira district where land-owning farmers were protesting increased land-revenue and the other in the city of Ahmedabad, where workers in an Indian-owned textile mill were distressed about their low wages. The satyagraha in Ahmedabad took the form of Gandhi fasting and supporting the workers in a strike, which eventually led to a settlement. In Kaira, in contrast, although the farmers' cause received publicity from Gandhi's presence, the satyagraha itself, which consisted of the farmers' collective decision to withhold payment, was not immediately successful, as the British authorities refused to back down. The agitation in Kaira gained for Gandhi another lifelong lieutenant in Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, who had organised the farmers, and who too would go on to play a leadership role in the Indian independence movement.[79]

1916–1919: Montagu–Chelmsford reforms

In 1916, in the face of new strength demonstrated by the nationalists with the signing of the Lucknow Pact and the founding of the Home Rule leagues, and the realisation, after the disaster in the Mesopotamian campaign, that the war would likely last longer, the new viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, cautioned that the Government of India needed to be more responsive to Indian opinion.[80] Towards the end of the year, after discussions with the government in London, he suggested that the British demonstrate their good faith—in light of the Indian war role—through a number of public actions, including awards of titles and honours to princes, granting of commissions in the army to Indians, and removal of the much-reviled cotton excise duty, but, most importantly, an announcement of Britain's future plans for India and an indication of some concrete steps. After more discussion, in August 1917, the new Liberal secretary of state for India, Edwin Montagu, announced the British aim of "increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration, and the gradual development of self-governing institutions, with a view to the progressive realisation of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire".[80] Although the plan envisioned limited self-government at first only in the provinces—with India emphatically within the British Empire—it represented the first British proposal for any form of representative government in a non-white colony.

Montagu and Chelmsford presented their report in July 1918 after a long fact-finding trip through India the previous winter.[81] After more discussion by the government and parliament in Britain, and another tour by the Franchise and Functions Committee for the purpose of identifying who among the Indian population could vote in future elections, the Government of India Act 1919 (also known as the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms) was passed in December 1919.[81] The new Act enlarged both the provincial and Imperial legislative councils and repealed the Government of India's recourse to the "official majority" in unfavourable votes.[81] Although departments like defence, foreign affairs, criminal law, communications, and income-tax were retained by the Viceroy and the central government in New Delhi, other departments like public health, education, land-revenue, local self-government were transferred to the provinces.[81] The provinces themselves were now to be administered under a new diarchical system, whereby some areas like education, agriculture, infrastructure development, and local self-government became the preserve of Indian ministers and legislatures, and ultimately the Indian electorates, while others like irrigation, land-revenue, police, prisons, and control of media remained within the purview of the British governor and his executive council.[81] The new Act also made it easier for Indians to be admitted into the civil services and the army officer corps.

A greater number of Indians were now enfranchised, although, for voting at the national level, they constituted only 10% of the total adult male population, many of whom were still illiterate.[81] In the provincial legislatures, the British continued to exercise some control by setting aside seats for special interests they considered cooperative or useful. In particular, rural candidates, generally sympathetic to British rule and less confrontational, were assigned more seats than their urban counterparts.[81] Seats were also reserved for non-Brahmins, landowners, businessmen, and college graduates. The principal of "communal representation", an integral part of the Minto–Morley Reforms, and more recently of the Congress-Muslim League Lucknow Pact, was reaffirmed, with seats being reserved for Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and domiciled Europeans, in both provincial and Imperial legislative councils.[81] The Montagu–Chelmsford reforms offered Indians the most significant opportunity yet for exercising legislative power, especially at the provincial level; however, that opportunity was also restricted by the still limited number of eligible voters, by the small budgets available to provincial legislatures, and by the presence of rural and special interest seats that were seen as instruments of British control.[81] Its scope was unsatisfactory to the Indian political leadership, famously expressed by Annie Besant as something "unworthy of England to offer and India to accept".[82]

1917–1919: Rowlatt Act

In 1917, as Montagu and Chelmsford were compiling their report, a committee chaired by a British judge, Sidney Rowlatt, and was tasked with investigating "revolutionary conspiracies", with the unstated goal of extending the government's wartime powers.[80] The Rowlatt Committee comprised four British and two Indian members, including Sir Basil Scott and Diwan Bahadur Sir C. V. Kumaraswami Sastri, the present and future Chief Justices of the High Court of Bombay and the High Court of Madras. It presented its report in July 1918 and identified three regions of conspiratorial insurgency: Bengal, the Bombay presidency, and the Punjab.[80] To combat subversive acts in these regions, the committee unanimously recommended that the government use emergency powers akin to its wartime authority, which included the ability to try cases of sedition by a panel of three judges and without juries, exaction of securities from suspects, governmental overseeing of residences of suspects,[80] and the power for provincial governments to arrest and detain suspects in short-term detention facilities and without trial.[83]

With the end of World War I, there was also a change in the economic climate. By the end of 1919, 1.5 million Indians had served in the armed services in either combatant or non-combatant roles, and India had provided £146 million in revenue for the war.[84] The increased taxes coupled with disruptions in both domestic and international trade had the effect of approximately doubling the index of overall prices in India between 1914 and 1920.[84] Returning war veterans, especially in the Punjab, created a growing unemployment crisis,[85] and post-war inflation led to food riots in Bombay, Madras, and Bengal provinces,[85] a situation that was made only worse by the failure of the 1918–19 monsoon and by profiteering and speculation.[84] The global influenza epidemic and the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 added to the general jitters; the former among the population already experiencing economic woes,[85] and the latter among government officials, fearing a similar revolution in India.[86]

To combat what it saw as a coming crisis, the government now drafted the Rowlatt committee's recommendations into two Rowlatt Bills.[83] Although the bills were authorised for legislative consideration by Edwin Montagu, they were done so unwillingly, with the accompanying declaration, "I loathe the suggestion at first sight of preserving the Defence of India Act in peacetime to such an extent as Rowlatt and his friends think necessary."[80] In the ensuing discussion and vote in the Imperial Legislative Council, all Indian members voiced opposition to the bills. The Government of India was, nevertheless, able to use of its "official majority" to ensure passage of the bills early in 1919.[80] However, what it passed, in deference to the Indian opposition, was a lesser version of the first bill, which now allowed extrajudicial powers, but for a period of exactly three years and for the prosecution solely of "anarchical and revolutionary movements", dropping entirely the second bill involving modification the Indian Penal Code.[80] Even so, when it was passed, the new Rowlatt Act aroused widespread indignation throughout India, and brought Gandhi to the forefront of the nationalist movement.[83]

1919–1939: Jallianwala, non-cooperation, GOI Act 1935

-

Gandhi with Besant en route to a meeting in Madras in September 1921. Earlier, in Madurai, on 21 September 1921, Gandhi had adopted the loin-cloth in identification with India's poor.

-

Poster advertising a Congress non-co-operation "Public Meeting" and a "Bonfire of Foreign Clothes" in Bombay, early 1920s, and expressing support for the "Karachi Khilafat Conference"

-

Hindus and Muslims, with flags of Indian National Congress and the Muslim League, collecting clothes to be burnt as a part of the non-cooperation movement

-

Staff and students, National College, Lahore, founded in 1921 by Lala Lajpat Rai after the non-co-operation movement. Standing, fourth from right is Bhagat Singh.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk