A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Algerian War ثورة التحرير الجزائرية Guerre d'Algérie | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and the decolonisation of Africa | ||||||||||

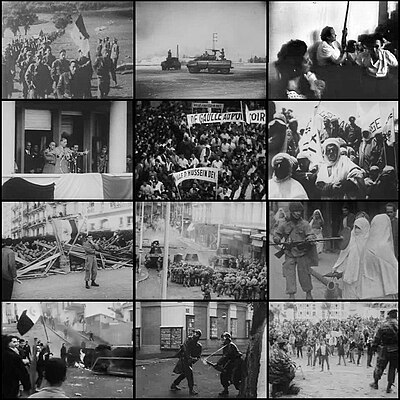

Collage of the French war in Algeria | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

Politicians:

|

| |||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||||

|

300,000 identified 40,000 civilian support | 3,000 (OAS) | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||||

|

|

| |||||||||

~1,500,000 total Algerian deaths (Algerian historians' estimate)[29]

| ||||||||||

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

The Algerian War (also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence)[nb 1] was a major armed conflict between France and the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) from 1954 to 1962, which led to Algeria winning its independence from France.[34] An important decolonization war, it was a complex conflict characterized by guerrilla warfare and war crimes. The conflict also became a civil war between the different communities and within the communities.[35] The war took place mainly on the territory of Algeria, with repercussions in metropolitan France.

Effectively started by members of the National Liberation Front (FLN) on 1 November 1954, during the Toussaint Rouge ("Red All Saints' Day"), the conflict led to serious political crises in France, causing the fall of the Fourth Republic (1946–58), to be replaced by the Fifth Republic with a strengthened presidency. The brutality of the methods employed by the French forces failed to win hearts and minds in Algeria, alienated support in metropolitan France, and discredited French prestige abroad.[36][37] As the war dragged on, the French public slowly turned against it[38] and many of France's key allies, including the United States, switched from supporting France to abstaining in the UN debate on Algeria.[39] After major demonstrations in Algiers and several other cities in favor of independence (1960)[40][41] and a United Nations resolution recognizing the right to independence,[42] Charles de Gaulle, the first president of the Fifth Republic, decided to open a series of negotiations with the FLN. These concluded with the signing of the Évian Accords in March 1962. A referendum took place on 8 April 1962 and the French electorate approved the Évian Accords. The final result was 91% in favor of the ratification of this agreement[43] and on 1 July, the Accords were subject to a second referendum in Algeria, where 99.72% voted for independence and just 0.28% against.[44]

The planned French withdrawal led to a state crisis. This included various assassination attempts on de Gaulle as well as some attempts at military coups. Most of the former were carried out by the Organisation armée secrète (OAS), an underground organization formed mainly from French military personnel supporting a French Algeria, which committed a large number of bombings and murders both in Algeria and in the homeland to stop the planned independence.

The war caused the deaths of between 400,000 and 1,500,000 Algerians,[45][29][27] 25,600 French soldiers,[20]: 538 and 6,000 Europeans. War crimes committed during the war included massacres of civilians, rape, and torture; the French destroyed over 8,000 villages and relocated over 2 million Algerians to concentration camps.[46][47] Upon independence in 1962, 900,000 European-Algerians (Pieds-noirs) fled to France within a few months in fear of the FLN's revenge. The French government was unprepared to receive such a vast number of refugees, which caused turmoil in France. The majority of Algerian Muslims who had worked for the French were disarmed and left behind, as the agreement between French and Algerian authorities declared that no actions could be taken against them.[48] However, the Harkis in particular, having served as auxiliaries with the French army, were regarded as traitors and many were murdered by the FLN or by lynch mobs, often after being abducted and tortured.[20]: 537 [49] About 20,000 Harki families (around 90,000 people) managed to flee to France, some with help from their French officers acting against orders, and today they and their descendants form a significant part of the population of Algerians in France.[citation needed]

Background

Conquest of Algeria

On the pretext of a slight to their consul, the French invaded Algeria in 1830.[20] Directed by Marshall Bugeaud, who became the first Governor-General of Algeria, the conquest was violent and marked by a "scorched earth" policy designed to reduce the power of the native rulers, the Dey, including massacres, mass rapes and other atrocities.[50][51] Between 500,000 and 1,000,000, from approximately 3 million Algerians, were killed in the first three decades of the conquest.[52][53] French losses from 1830 to 1851 were 3,336 killed in action and 92,329 dying in hospital.[54]

In 1834, Algeria became a French military colony. It was declared by the Constitution of 1848 to be an integral part of France and was divided into three departments: Alger, Oran and Constantine. Many French and other Europeans (Spanish, Italians, Maltese and others) later settled in Algeria.

Under the Second Empire (1852–1871), the Code de l'indigénat (Indigenous Code) was implemented by the sénatus-consulte of 14 July 1865. It allowed Muslims to apply for full French citizenship, a measure that few took since it involved renouncing the right to be governed by sharia law in personal matters and was widely considered to be apostasy. Its first article stipulated:

The indigenous Muslim is French; however, he will continue to be subjected to Muslim law. He may be admitted to serve in the army (armée de terre) and the navy (armée de mer). He may be called to functions and civil employment in Algeria. He may, on his demand, be admitted to enjoy the rights of a French citizen; in this case, he is subjected to the political and civil laws of France.[55]

Prior to 1870, fewer than 200 demands were registered by Muslims and 152 by Jewish Algerians.[56] The 1865 decree was then modified by the 1870 Crémieux Decree, which granted French nationality to Jews living in one of the three Algerian departments. In 1881, the Code de l'Indigénat made the discrimination official by creating specific penalties for indigènes and organising the seizure or appropriation of their lands.[56]

After World War II, equality of rights was proclaimed by the ordonnance of 7 March 1944 and later confirmed by the loi Lamine Guèye of 7 May 1946, which granted French citizenship to all subjects of France's territories and overseas departments, and by the 1946 Constitution. The Law of 20 September 1947 granted French citizenship to all Algerian subjects, who were not required to renounce their Muslim personal status.[57][dubious ]

Algeria was unique to France because unlike all other overseas possessions acquired by France during the 19th century, Algeria was considered and legally classified to be an integral part of France.

Algerian Nationalism

Both Muslim and European Algerians took part in World War II and fought for France. Algerian Muslims served as tirailleurs (such regiments were created as early as 1842[58]) and spahis; and French settlers as Zouaves or Chasseurs d'Afrique. US President Woodrow Wilson's 1918 Fourteen Points had the fifth read: "A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined." Some Algerian intellectuals, dubbed oulémas, began to nurture the desire for independence or, at the very least, autonomy and self-rule.[59]

Within that context, Khalid ibn Hashim, a grandson of Abd el-Kadir, spearheaded the resistance against the French in the first half of the 20th century and was a member of the directing committee of the French Communist Party. In 1926, he founded the Étoile Nord-Africaine ("North African Star"), to which Messali Hadj, also a member of the Communist Party and of its affiliated trade union, the Confédération générale du travail unitaire (CGTU), joined the following year.[60]

The North African Star broke from the Communist Party in 1928, before being dissolved in 1929 at Paris's demand. Amid growing discontent from the Algerian population, the Third Republic (1871–1940) acknowledged some demands, and the Popular Front initiated the Blum-Viollette proposal in 1936, which was supposed to enlighten the Indigenous Code by giving French citizenship to a small number of Muslims. The pieds-noirs (Algerians of European origin) violently demonstrated against it and the North African Party also opposed it, leading to its abandonment. The pro-independence party was dissolved in 1937, and its leaders were charged with the illegal reconstitution of a dissolved league, leading to Messali Hadj's 1937 founding of the Parti du peuple algérien (Algerian People's Party, PPA), which, no longer espoused full independence but only extensive autonomy. This new party was dissolved in 1939. Under Vichy France, the French State attempted to abrogate the Crémieux Decree to suppress the Jews' French citizenship, but the measure was never implemented.[citation needed]

On the other hand, the nationalist leader Ferhat Abbas founded the Algerian Popular Union (Union populaire algérienne) in 1938. In 1943, Abbas wrote the Algerian People's Manifesto (Manifeste du peuple algérien). Arrested after the Sétif and Guelma massacre of May 8, 1945, when the French Army and pieds-noirs mobs killed between 6,000 and 30,000 Algerians,[61][20]: 27 Abbas founded the Democratic Union of the Algerian Manifesto (UDMA) in 1946 and was elected as a deputy. Founded in 1954, the National Liberation Front (FLN) created an armed wing, the Armée de Libération Nationale (National Liberation Army) to engage in an armed struggle against French authority. Many Algerian soldiers served for the French Army in the First Indochina War had strong sympathy for the Vietnamese fighting against France and took up their experience to support the ALN.[62][63]

France, which had just lost French Indochina, was determined not to lose the next colonial war, particularly in its oldest and nearest major colony, which was regarded as a part of Metropolitan France (rather than a colony), by French law.[64]

War chronology

Beginning of hostilities

In the early morning hours of 1 November 1954, FLN maquisards (guerrillas) attacked military and civilian targets throughout Algeria in what became known as the Toussaint Rouge (Red All-Saints' Day). From Cairo, the FLN broadcast the declaration of 1 November 1954 written by the journalist Mohamed Aïchaoui calling on Muslims in Algeria to join in a national struggle for the "restoration of the Algerian state – sovereign, democratic and social – within the framework of the principles of Islam." It was the reaction of Premier Pierre Mendès France (Radical-Socialist Party), who only a few months before had completed the liquidation of France's tete empire in Indochina, which set the tone of French policy for five years. He declared in the National Assembly, "One does not compromise when it comes to defending the internal peace of the nation, the unity and integrity of the Republic. The Algerian departments are part of the French Republic. They have been French for a long time, and they are irrevocably French. ... Between them and metropolitan France there can be no conceivable secession." At first, and despite the Sétif massacre of 8 May 1945, and the pro-Independence struggle before World War II, most Algerians were in favor of a relative status-quo. While Messali Hadj had radicalized by forming the FLN, Ferhat Abbas maintained a more moderate, electoral strategy. Fewer than 500 fellaghas (pro-Independence fighters) could be counted at the beginning of the conflict.[65] The Algerian population radicalized itself in particular because of the terrorist acts of French-sponsored Main Rouge (Red Hand) group, which targeted anti-colonialists in all of the Maghreb region (Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria), killing, for example, Tunisian activist Farhat Hached in 1952.[65]

FLN

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

The FLN uprising presented nationalist groups with the question of whether to adopt armed revolt as the main course of action. During the first year of the war, Ferhat Abbas's Democratic Union of the Algerian Manifesto (UDMA), the ulema, and the Algerian Communist Party (PCA) maintained a friendly neutrality toward the FLN. The communists, who had made no move to cooperate in the uprising at the start, later tried to infiltrate the FLN, but FLN leaders publicly repudiated the support of the party. In April 1956, Abbas flew to Cairo, where he formally joined the FLN. This action brought in many évolués who had supported the UDMA in the past. The AUMA also threw the full weight of its prestige behind the FLN. Bendjelloul and the pro-integrationist moderates had already abandoned their efforts to mediate between the French and the rebels.

After the collapse of the MTLD, the veteran nationalist Messali Hadj formed the leftist Mouvement National Algérien (MNA), which advocated a policy of violent revolution and total independence similar to that of the FLN, but aimed to compete with that organisation. The Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN), the military wing of the FLN, subsequently wiped out the MNA guerrilla operation in Algeria, and Messali Hadj's movement lost what little influence it had had there. However, the MNA retained the support of many Algerian workers in France through the Union Syndicale des Travailleurs Algériens (the Union of Algerian Workers). The FLN also established a strong organization in France to oppose the MNA. The "Café wars", resulting in nearly 5,000 deaths, were waged in France between the two rebel groups throughout the years of the War of Independence.

On the political front, the FLN worked to persuade—and to coerce—the Algerian masses to support the aims of the independence movement through contributions. FLN-influenced labor unions, professional associations, and students' and women's organizations were created to lead opinion in diverse segments of the population, but here too, violent coercion was widely used. Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist from Martinique who became the FLN's leading political theorist, provided a sophisticated intellectual justification for the use of violence in achieving national liberation.[66][page needed] From Cairo, Ahmed Ben Bella ordered the liquidation of potential interlocuteurs valables, those independent representatives of the Muslim community acceptable to the French through whom a compromise or reforms within the system might be achieved.

As the FLN campaign of influence spread through the countryside, many European farmers in the interior (called Pieds-Noirs), many of whom lived on lands taken from Muslim communities during the nineteenth century,[67] sold their holdings and sought refuge in Algiers and other Algerian cities. After a series of bloody, random massacres and bombings by Muslim Algerians in several towns and cities, the French Pieds-Noirs and urban French population began to demand that the French government engage in sterner countermeasures, including the proclamation of a state of emergency, capital punishment for political crimes, denunciation of all separatists, and most ominously, a call for 'tit-for-tat' reprisal operations by police, military, and para-military forces. Colon vigilante units, whose unauthorized activities were conducted with the passive cooperation of police authorities, carried out ratonnades (literally, rat-hunts, raton being a racist term for denigrating Muslim Algerians) against suspected FLN members of the Muslim community.

By 1955, effective political action groups within the Algerian colonial community succeeded in convincing many of the Governors General sent by Paris that the military was not the way to resolve the conflict. A major success was the conversion of Jacques Soustelle, who went to Algeria as governor general in January 1955 determined to restore peace. Soustelle, a one-time leftist and by 1955 an ardent Gaullist, began an ambitious reform program (the Soustelle Plan) aimed at improving economic conditions among the Muslim population.

After the Philippeville massacre

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

The FLN adopted tactics similar to those of nationalist groups in Asia, and the French did not realize the seriousness of the challenge they faced until 1955, when the FLN moved into urbanized areas. An important watershed in the War of Independence was the massacre of Pieds-Noirs civilians by the FLN near the town of Philippeville (now known as Skikda) in August 1955. Before this operation, FLN policy was to attack only military and government-related targets. The commander of the Constantine wilaya/region, however, decided a drastic escalation was needed. The killing by the FLN and its supporters of 123 people, including 71 French,[68] including old women and babies, shocked Jacques Soustelle into calling for more repressive measures against the rebels. The French authorities stated that 1,273 guerrillas died in what Soustelle admitted were "severe" reprisals. The FLN subsequently claimed that 12,000 Muslims were killed.[20]: 122 Soustelle's repression was an early cause of the Algerian population's rallying to the FLN.[68] After Philippeville, Soustelle declared sterner measures and an all-out war began. In 1956, demonstrations by French Algerians caused the French government to not make reforms.

Soustelle's successor, Governor General Robert Lacoste, a socialist, abolished the Algerian Assembly. Lacoste saw the assembly, which was dominated by pieds-noirs, as hindering the work of his administration, and he undertook the rule of Algeria by decree. He favored stepping up French military operations and granted the army exceptional police powers—a concession of dubious legality under French law—to deal with the mounting political violence. At the same time, Lacoste proposed a new administrative structure to give Algeria some autonomy and a decentralized government. Whilst remaining an integral part of France, Algeria was to be divided into five districts, each of which would have a territorial assembly elected from a single slate of candidates. Until 1958, deputies representing Algerian districts were able to delay the passage of the measure by the National Assembly of France.

In August and September 1956, the leadership of the FLN guerrillas operating within Algeria (popularly known as "internals") met to organize a formal policy-making body to synchronize the movement's political and military activities. The highest authority of the FLN was vested in the thirty-four member National Council of the Algerian Revolution (Conseil National de la Révolution Algérienne, CNRA), within which the five-man Committee of Coordination and Enforcement (Comité de Coordination et d'Exécution, CCE) formed the executive. The leadership of the regular FLN forces based in Tunisia and Morocco ("externals"), including Ben Bella, knew the conference was taking place but by chance or design on the part of the "internals" were unable to attend.

In October 1956, the French Air Force intercepted a Moroccan DC-3 plane bound for Tunis, carrying Ahmed Ben Bella, Mohammed Boudiaf, Mohamed Khider and Hocine Aït Ahmed, and forced it to land in Algiers. Lacoste had the FLN external political leaders arrested and imprisoned for the duration of the war. This action caused the remaining rebel leaders to harden their stance.

France opposed Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser's material and political assistance to the FLN, which some French analysts believed was the revolution's main sustenance. This attitude was a factor in persuading France to participate in the November 1956 attempt to seize the Suez Canal during the Suez Crisis.

During 1957, support for the FLN weakened as the breach between the internals and externals widened. To halt the drift, the FLN expanded its executive committee to include Abbas, as well as imprisoned political leaders such as Ben Bella. It also convinced communist and Arab members of the United Nations (UN) to put diplomatic pressure on the French government to negotiate a cease-fire. In 1957, it became common knowledge in France that the French Army was routinely using torture to extract information from suspected FLN members.[69] Hubert Beuve-Méry, the editor of Le Monde, declared in an edition on 13 March 1957: "From now on, Frenchman must know that they don't have the right to condemn in the same terms as ten years ago the destruction of Oradour and the torture by the Gestapo."[69] Another case that attracted much media attention was the murder of Maurice Audin, a member of the outlawed Algerian Communist party,[70] mathematics professor at the University of Algiers and a suspected FLN member whom the French Army arrested in June 1957.[69]: 224 Audin was tortured and killed and his body was never found.[69] As Audin was French rather than Algerian, his "disappearance" while in the custody of the French Army led to the case becoming a cause célèbre as his widow aided by the historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet determinedly sought to have the men responsible for her husband's death prosecuted.[69]

Existentialist writer, philosopher and playwright Albert Camus, native of Algiers, tried unsuccessfully to persuade both sides to at least leave civilians alone, writing editorials against the use of torture in Combat newspaper. The FLN considered him a fool, and some Pieds-Noirs considered him a traitor. Nevertheless, in his speech when he received the Nobel Prize in Literature, Camus said that when faced with a radical choice he would eventually support his community. This statement made him lose his status among left-wing intellectuals; when he died in 1960 in a car crash, the official thesis of an ordinary accident (a quick open-and-shut case) left more than a few observers doubtful. His widow claimed that Camus, though discreet, was in fact an ardent supporter of French Algeria in the last years of his life.[citation needed]

Battle of Algiers

To increase international and domestic French attention to their struggle, the FLN decided to bring the conflict to the cities and to call a nationwide general strike and also to plant bombs in public places. The most notable instance was the Battle of Algiers, which began on September 30, 1956, when three women, including Djamila Bouhired and Zohra Drif, simultaneously placed bombs at three sites including the downtown office of Air France. The FLN carried out shootings and bombings in the spring of 1957, resulting in civilian casualties and a crushing response from the authorities.

General Jacques Massu was instructed to use whatever methods deemed necessary to restore order in the city and to find and eliminate terrorists. Using paratroopers, he broke the strike and, in the succeeding months, destroyed the FLN infrastructure in Algiers. But the FLN had succeeded in showing its ability to strike at the heart of French Algeria and to assemble a mass response to its demands among urban Muslims. The publicity given to the brutal methods used by the army to win the Battle of Algiers, including the use of torture, strong movement control and curfew called quadrillage and where all authority was under the military, created doubt in France about its role in Algeria. What was originally "pacification" or a "public order operation" had turned into a colonial war accompanied by torture.

Guerrilla war

During 1956 and 1957, the FLN successfully applied hit-and-run tactics in accordance with guerrilla warfare theory. Whilst some of this was aimed at military targets, a significant amount was invested in a terror campaign against those in any way deemed to support or encourage French authority. This resulted in acts of sadistic torture and brutal violence against all, including women and children. Specializing in ambushes and night raids and avoiding direct contact with superior French firepower, the internal forces targeted army patrols, military encampments, police posts, and colonial farms, mines, and factories, as well as transportation and communications facilities. Once an engagement was broken off, the guerrillas merged with the population in the countryside, in accordance with Mao's theories.

Although successfully provoking fear and uncertainty within both communities in Algeria, the revolutionaries' coercive tactics suggested that they had not yet inspired the bulk of the Muslim people to revolt against French colonial rule. Gradually, however, the FLN gained control in certain sectors of the Aurès, the Kabylie, and other mountainous areas around Constantine and south of Algiers and Oran. In these places, the FLN established a simple but effective—although frequently temporary—military administration that was able to collect taxes and food and to recruit manpower.[71] But it was never able to hold large, fixed positions.

The loss of competent field commanders both on the battlefield and through defections and political purges created difficulties for the FLN. Moreover, power struggles in the early years of the war split leadership in the wilayat, particularly in the Aurès. Some officers created their own fiefdoms, using units under their command to settle old scores and engage in private wars against military rivals within the FLN.

French counter-insurgency operations

Despite complaints from the military command in Algiers, the French government was reluctant for many months to admit that the Algerian situation was out of control and that what was viewed officially as a pacification operation had developed into a war. By 1956, there were more than 400,000 French troops in Algeria. Although the elite airborne infantry units of the Troupes coloniales and the Foreign Legion bore the brunt of offensive counterinsurgency combat operations, approximately 170,000 Muslim Algerians also served in the regular French army, most of them volunteers. France also sent air force and naval units to the Algerian theater, including helicopters. In addition to service as a flying ambulance and cargo carrier, French forces utilized the helicopter for the first time in a ground attack role in order to pursue and destroy fleeing FLN guerrilla units. The American military later used the same helicopter combat methods in the Vietnam War. The French also used napalm.[72]

The French army resumed an important role in local Algerian administration through the Special Administration Section (Section Administrative Spécialisée, SAS), created in 1955. The SAS's mission was to establish contact with the Muslim population and weaken nationalist influence in the rural areas by asserting the "French presence" there. SAS officers—called képis bleus (blue caps)—also recruited and trained bands of loyal Muslim irregulars, known as harkis. Armed with shotguns and using guerrilla tactics similar to those of the FLN, the harkis, who eventually numbered about 180,000 volunteers, more than the FLN activists,[15] were an ideal instrument of counterinsurgency warfare.

Harkis were mostly used in conventional formations, either in all-Algerian units commanded by French officers or in mixed units. Other uses included platoon or smaller size units, attached to French battalions, in a similar way as the Kit Carson Scouts by the U.S. in Vietnam. A third use was an intelligence gathering role, with some reported minor pseudo-operations in support of their intelligence collection.[73] U.S. military expert Lawrence E. Cline stated, "The extent of these pseudo-operations appears to have been very limited both in time and scope. ... The most widespread use of pseudo type operations was during the 'Battle of Algiers' in 1957. The principal French employer of covert agents in Algiers was the Fifth Bureau, the psychological warfare branch. "The Fifth Bureau" made extensive use of 'turned' FLN members, one such network being run by Captain Paul-Alain Leger of the 10th Paras. "Persuaded" to work for the French forces included by the use of torture and threats against their family; these agents "mingled with FLN cadres. They planted incriminating forged documents, spread false rumors of treachery and fomented distrust. ... As a frenzy of throat-cutting and disemboweling broke out among confused and suspicious FLN cadres, nationalist slaughtered nationalist from April to September 1957 and did France's work for her."[74] But this type of operation involved individual operatives rather than organized covert units.

One organized pseudo-guerrilla unit, however, was created in December 1956 by the French DST domestic intelligence agency. The Organization of the French Algerian Resistance (ORAF), a group of counter-terrorists had as its mission to carry out false flag terrorist attacks with the aim of quashing any hopes of political compromise.[75] But it seemed that, as in Indochina, "the French focused on developing native guerrilla groups that would fight against the FLN", one of whom fought in the Southern Atlas Mountains, equipped by the French Army.[76]

The FLN also used pseudo-guerrilla strategies against the French Army on one occasion, with Force K, a group of 1,000 Algerians who volunteered to serve in Force K as guerrillas for the French. But most of these members were either already FLN members or were turned by the FLN once enlisted. Corpses of purported FLN members displayed by the unit were in fact those of dissidents and members of other Algerian groups killed by the FLN. The French Army finally discovered the war ruse and tried to hunt down Force K members. However, some 600 managed to escape and join the FLN with weapons and equipment.[76][20]: 255–7

Late in 1957, General Raoul Salan, commanding the French Army in Algeria, instituted a system of quadrillage (surveillance using a grid pattern), dividing the country into sectors, each permanently garrisoned by troops responsible for suppressing rebel operations in their assigned territory. Salan's methods sharply reduced the instances of FLN terrorism but tied down a large number of troops in static defense. Salan also constructed a heavily patrolled system of barriers to limit infiltration from Tunisia and Morocco. The best known of these was the Morice Line (named for the French defense minister, André Morice), which consisted of an electrified fence, barbed wire, and mines over a 320-kilometer stretch of the Tunisian border. Despite ruthless clashes during the Battle of the borders, the ALN failed to penetrate these defence lines.[citation needed]

The French military command ruthlessly applied the principle of collective responsibility to villages suspected of sheltering, supplying, or in any way cooperating with the guerrillas. Villages that could not be reached by mobile units were subject to aerial bombardment. FLN guerrillas that fled to caves or other remote hiding places were tracked and hunted down. In one episode, FLN guerrillas who refused to surrender and withdraw from a cave complex were dealt with by French Foreign Legion Pioneer troops, who, lacking flamethrowers or explosives, simply bricked up each cave, leaving the residents to die of suffocation.[77]

Finding it impossible to control all of Algeria's remote farms and villages, the French government also initiated a program of concentrating large segments of the rural population, including whole villages, in camps under military supervision to prevent them from aiding the rebels. In the three years (1957–60) during which the regroupement program was followed, more than 2 million Algerians[33] were removed from their villages, mostly in the mountainous areas, and resettled in the plains, where it was difficult to reestablish their previous economic and social systems. Living conditions in the fortified villages were poor. In hundreds of villages, orchards and croplands not already burned by French troops went to seed for lack of care. These population transfers effectively denied the use of remote villages to FLN guerrillas, who had used them as a source of rations and manpower, but also caused significant resentment on the part of the displaced villagers. Relocation's social and economic disruption continued to be felt a generation later.[citation needed] At the same time, the French tried to gain support from the civilian population by providing money, jobs and housing to farmers[47]

The French Army shifted its tactics at the end of 1958 from dependence on quadrillage to the use of mobile forces deployed on massive search-and-destroy missions against FLN strongholds. In 1959, Salan's successor, General Maurice Challe, appeared to have suppressed major rebel resistance, but political developments had already overtaken the French Army's successes.[citation needed]

Fall of the Fourth Republic

Recurrent cabinet crises focused attention on the inherent instability of the Fourth Republic and increased the misgivings of the army and of the pieds-noirs that the security of Algeria was being undermined by party politics. Army commanders chafed at what they took to be inadequate and incompetent political initiatives by the government in support of military efforts to end the rebellion. The feeling was widespread that another debacle like that of Indochina in 1954 was in the offing and that the government would order another precipitate pullout and sacrifice French honor to political expediency. Many saw in de Gaulle, who had not held office since 1946, the only public figure capable of rallying the nation and giving direction to the French government.

After his time as governor general, Soustelle returned to France to organize support for de Gaulle's return to power, while retaining close ties to the army and the pieds-noirs. By early 1958, he had organized a coup d'état, bringing together dissident army officers and pieds-noirs with sympathetic Gaullists. An army junta under General Massu seized power in Algiers on the night of May 13, thereafter known as the May 1958 crisis. General Salan assumed leadership of a Committee of Public Safety formed to replace the civil authority and pressed the junta's demands that de Gaulle be named by French president René Coty to head a government of national unity invested with extraordinary powers to prevent the "abandonment of Algeria."

On May 24, French paratroopers from the Algerian corps landed on Corsica, taking the French island in a bloodless action. Subsequently, preparations were made in Algeria for Operation Resurrection, which had as its objectives the seizure of Paris and the removal of the French government. Resurrection was to be implemented in the event of one of three following scenarios: Were de Gaulle not approved as leader of France by the parliament; were de Gaulle to ask for military assistance to take power; or if it seemed that communist forces were making any move to take power in France. De Gaulle was approved by the French parliament on May 29, by 329 votes against 224, 15 hours before the projected launch of Operation Resurrection. This indicated that the Fourth Republic by 1958 no longer had any support from the French Army in Algeria and was at its mercy even in civilian political matters. This decisive shift in the balance of power in civil-military relations in France in 1958, and the threat of force, was the primary factor in the return of de Gaulle to power in France.

De Gaulle

Many people, regardless of citizenship, greeted de Gaulle's return to power as the breakthrough needed to end the hostilities. On his trip to Algeria on 4 June 1958, de Gaulle calculatedly made an ambiguous and broad emotional appeal to all the inhabitants, declaring, "Je vous ai compris" ("I have understood you"). De Gaulle raised the hopes of the pied-noir and the professional military, disaffected by the indecisiveness of previous governments, with his exclamation of "Vive l'Algérie française" ("Long live French Algeria") to cheering crowds in Mostaganem. At the same time, he proposed economic, social, and political reforms to improve the situation of the Muslims. Nonetheless, de Gaulle later admitted to having harbored deep pessimism about the outcome of the Algerian situation even then. Meanwhile, he looked for a "third force" among the population of Algeria, uncontaminated by the FLN or the "ultras" (colon extremists), through whom a solution might be found.

De Gaulle immediately appointed a committee to draft a new constitution for France's Fifth Republic, which would be declared early the next year, with which Algeria would be associated but of which it would not form an integral part. All Muslims, including women, were registered for the first time on electoral rolls to participate in a referendum to be held on the new constitution in September 1958.

De Gaulle's initiative threatened the FLN with decreased support among Muslims. In reaction, the FLN set up the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (Gouvernement Provisoire de la République Algérienne, GPRA), a government-in-exile headed by Abbas and based in Tunis. Before the referendum, Abbas lobbied for international support for the GPRA, which was quickly recognized by Morocco, Tunisia, China, and several other African, Arab, and Asian countries, but not by the Soviet Union.

In February 1959, de Gaulle was elected president of the new Fifth Republic. He visited Constantine in October to announce a program to end the war and create an Algeria closely linked to France. De Gaulle's call on the rebel leaders to end hostilities and to participate in elections was met with adamant refusal. "The problem of a cease-fire in Algeria is not simply a military problem", said the GPRA's Abbas. "It is essentially political, and negotiation must cover the whole question of Algeria." Secret discussions that had been underway were broken off.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Algerian_revolution

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk