A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

A caliphate or khilāfah (Arabic: خِلَافَةْ [xi'laːfah]) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph[1][2][3] (/ˈkælɪf, ˈkeɪ-/; Arabic: خَلِيفَةْ [xæ'liːfæh], ⓘ), a person considered a political-religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of the entire Muslim world (ummah).[4] Historically, the caliphates were polities based on Islam which developed into multi-ethnic trans-national empires.[5][6] During the medieval period, three major caliphates succeeded each other: the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661), the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), and the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1517). In the fourth major caliphate, the Ottoman Caliphate, the rulers of the Ottoman Empire claimed caliphal authority from 1517 until the caliphate was formally abolished as part of the 1924 secularisation of Turkey. Throughout the history of Islam, a few other Muslim states, almost all of which were hereditary monarchies such as the Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo) and Ayyubid Caliphate, have claimed to be caliphates.

Not all Muslim states have had caliphates. The Sunni branch of Islam stipulates that, as a head of state, a caliph should be elected by Muslims or their representatives.[7] Shiites, however, believe a caliph should be an imam chosen by God from the Ahl al-Bayt (the "Household of the Prophet").

In the early twenty-first century, following the failure of the Arab Spring and related protests, some have argued for a return to the concept of a caliphate to better unify Muslims.

Etymology

Before the advent of Islam, Arabian monarchs traditionally used the title malik (King), or another from the same root.[4]

The term caliph (/ˈkeɪlɪf, ˈkælɪf/),[8] derives from the Arabic word khalīfah (خَليفة, ⓘ), which means "successor", "steward", or "deputy" and has traditionally been considered a shortening of Khalīfah Rasūl Allāh ("successor of the messenger of God"). However, studies of pre-Islamic texts suggest that the original meaning of the phrase was "successor selected by God".[4]

History

Rashidun Caliphate (632–661)

Succession to Muhammad

In the immediate aftermath of the death of Muhammad, a gathering of the Ansar (natives of Medina) took place in the Saqifah (courtyard) of the Banu Sa'ida clan.[9] The general belief at the time was that the purpose of the meeting was for the Ansar to decide on a new leader of the Muslim community among themselves, with the intentional exclusion of the Muhajirun (migrants from Mecca), though this has later become the subject of debate.[10]

Nevertheless, Abu Bakr and Umar, both prominent companions of Muhammad, upon learning of the meeting became concerned of a potential coup and hastened to the gathering. Upon arriving, Abu Bakr addressed the assembled men with a warning that an attempt to elect a leader outside of Muhammad's own tribe, the Quraysh, would likely result in dissension as only they can command the necessary respect among the community. He then took Umar and another companion, Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah, by the hand and offered them to the Ansar as potential choices. He was countered with the suggestion that the Quraysh and the Ansar choose a leader each from among themselves, who would then rule jointly. The group grew heated upon hearing this proposal and began to argue amongst themselves. Umar hastily took Abu Bakr's hand and swore his own allegiance to the latter, an example followed by the gathered men.[11]

Abu Bakr was near-universally accepted as head of the Muslim community (under the title of caliph) as a result of Saqifah, though he did face contention as a result of the rushed nature of the event. Several companions, most prominent among them being Ali ibn Abi Talib, initially refused to acknowledge his authority.[12] Ali may have been reasonably expected to assume leadership, being both cousin and son-in-law to Muhammad.[13] The theologian Ibrahim al-Nakha'i stated that Ali also had support among the Ansar for his succession, explained by the genealogical links he shared with them. Whether his candidacy for the succession was raised during Saqifah is unknown, though it is not unlikely.[14] Abu Bakr later sent Umar to confront Ali to gain his allegiance, resulting in an altercation which may have involved violence.[15] However, after six months the group made peace with Abu Bakr and Ali offered him his fealty.[16]

Rāshidun Caliphs

Abu Bakr nominated Umar as his successor on his deathbed. Umar, the second caliph, was killed by a Persian slave called Abu Lu'lu'a Firuz. His successor, Uthman, was elected by a council of electors (majlis). Uthman was killed by members of a disaffected group. Ali then took control but was not universally accepted as caliph by the governors of Egypt and later by some of his own guard. He faced two major rebellions and was assassinated by Abd-al-Rahman ibn Muljam, a Khawarij. Ali's tumultuous rule lasted only five years. This period is known as the Fitna, or the first Islamic civil war. The followers of Ali later became the Shi'a ("shiaat Ali", partisans of Ali.[17]) minority sect of Islam and reject the legitimacy of the first three caliphs. The followers of all four Rāshidun Caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali) became the majority Sunni sect.

Under the Rāshidun, each region (Sultanate, Wilayah, or Emirate) of the caliphate had its own governor (Sultan, Wāli or Emir). Muāwiyah, a relative of Uthman and governor (wali) of Syria, succeeded Ali as caliph. Muāwiyah transformed the caliphate into a hereditary office, thus founding the Umayyad dynasty.

In areas which were previously under Sasanian Empire or Byzantine rule, the caliphs lowered taxes, provided greater local autonomy (to their delegated governors), greater religious freedom for Jews and some indigenous Christians, and brought peace to peoples demoralised and disaffected by the casualties and heavy taxation that resulted from the decades of Byzantine-Persian warfare.[18]

Ali's caliphate, Hasan and the rise of the Umayyad dynasty

Ali's reign was plagued by turmoil and internal strife. The Persians, taking advantage of this, infiltrated the two armies and attacked the other army causing chaos and internal hatred between the companions at the Battle of Siffin. The battle lasted several months, resulting in a stalemate. To avoid further bloodshed, Ali agreed to negotiate with Mu'awiyah. This caused a faction of approximately 4,000 people, who would come to be known as the Kharijites, to abandon the fight. After defeating the Kharijites at the Battle of Nahrawan, Ali was later assassinated by the Kharijite Ibn Muljam. Ali's son Hasan was elected as the next caliph, but abdicated in favour of Mu'awiyah a few months later to avoid any conflict within the Muslims. Mu'awiyah became the sixth caliph, establishing the Umayyad dynasty,[19] named after the great-grandfather of Uthman and Mu'awiyah, Umayya ibn Abd Shams.[20]

Umayyad Caliphate (661–750)

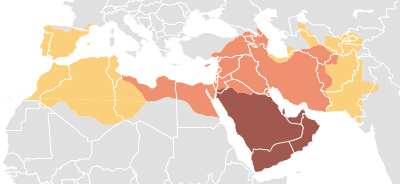

Beginning with the Umayyads, the title of the caliph became hereditary.[21] Under the Umayyads, the caliphate grew rapidly in territory, incorporating the Caucasus, Transoxiana, Sindh, the Maghreb and most of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) into the Muslim world.[22] At its greatest extent, the Umayyad Caliphate covered 5.17 million square miles (13,400,000 km2), making it the largest empire the world had yet seen and the seventh largest ever to exist in history.[23]

Geographically, the empire was divided into several provinces, the borders of which changed numerous times during the Umayyad reign.[citation needed] Each province had a governor appointed by the caliph. However, for a variety of reasons, including that they were not elected by Shura and suggestions of impious behaviour, the Umayyad dynasty was not universally supported within the Muslim community.[24] Some supported prominent early Muslims like Zubayr ibn al-Awwam; others felt that only members of Muhammad's clan, the Banu Hashim, or his own lineage, the descendants of Ali, should rule.[25]

There were numerous rebellions against the Umayyads, as well as splits within the Umayyad ranks (notably, the rivalry between Yaman and Qays).[26] At the command of Yazid son of Muawiya, an army led by Umar ibn Saad, a commander by the name of Shimr Ibn Thil-Jawshan killed Ali's son Hussein and his family at the Battle of Karbala in 680, solidifying the Shia-Sunni split.[17] Eventually, supporters of the Banu Hashim and the supporters of the lineage of Ali united to bring down the Umayyads in 750. However, the Shi‘at ‘Alī, "the Party of Ali", were again disappointed when the Abbasid dynasty took power, as the Abbasids were descended from Muhammad's uncle, ‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib and not from Ali.[27]

Abbasid Caliphate (750–1517)

Abbasid caliphs at Baghdad

In 750, the Umayyad dynasty was overthrown by another family of Meccan origin, the Abbasids. Their time represented a scientific, cultural and religious flowering.[28] Islamic art and music also flourished significantly during their reign.[29] Their major city and capital Baghdad began to flourish as a center of knowledge, culture and trade. This period of cultural fruition ended in 1258 with the sack of Baghdad by the Mongols under Hulagu Khan. The Abbasid Caliphate had, however, lost its effective power outside Iraq already by c. 920.[30] By 945, the loss of power became official when the Buyids conquered Baghdad and all of Iraq. The empire fell apart and its parts were ruled for the next century by local dynasties.[31]

In the ninth century, the Abbasids created an army loyal only to their caliphate, composed predominantly of Turkic Cuman, Circassian and Georgian slave origin known as Mamluks.[32][33] By 1250 the Mamluks came to power in Egypt. The Mamluk army, though often viewed negatively, both helped and hurt the caliphate. Early on, it provided the government with a stable force to address domestic and foreign problems. However, creation of this foreign army and al-Mu'tasim's transfer of the capital from Baghdad to Samarra created a division between the caliphate and the peoples they claimed to rule. In addition, the power of the Mamluks steadily grew until Ar-Radi (934–941) was constrained to hand over most of the royal functions to Muhammad ibn Ra'iq.

Under the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo (1261–1517)

In 1261, following the Mongol conquest of Baghdad, the Mamluk rulers of Egypt tried to gain legitimacy for their rule by declaring the re-establishment of the Abbasid caliphate in Cairo.[citation needed] The Abbasid caliphs in Egypt had no political power; they continued to maintain the symbols of authority, but their sway was confined to religious matters.[citation needed] The first Abbasid caliph of Cairo was Al-Mustansir (r. June–November 1261). The Abbasid caliphate of Cairo lasted until the time of Al-Mutawakkil III, who ruled as caliph from 1508 to 1516, then he was deposed briefly in 1516 by his predecessor Al-Mustamsik, but was restored again to the caliphate in 1517.[citation needed]

The Ottoman Great Sultan Selim I defeated the Mamluk Sultanate and made Egypt part of the Ottoman Empire in 1517. Al-Mutawakkil III was captured together with his family and transported to Constantinople as a prisoner where he had a ceremonial role. He died in 1543, following his return to Cairo.[34]

Parallel regional caliphates in the later Abbasid era

The Abbasid dynasty lost effective power over much of the Muslim realm by the first half of the tenth century.

The Umayyad dynasty, which had survived and come to rule over Al-Andalus, reclaimed the title of caliph in 929, lasting until it was overthrown in 1031.

Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba (929–1031)

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

1936

1995

2012

2012 Burgas bus bombing

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

2022 Sri Lankan protests

Abu Bakr

Adele Nicoll

Arabian Peninsula

Asparágus lekársky

Assassination of Shinzo Abe

Battle of the Yarmuk

Battle of Uhud

Bernard Toone

Bobsleigh

Broadway (Manhattan)

Broadway theatre

Broadway Theatre (53rd Street)

Burgas Airport

Caliphate

Card game

Chipper Jones

Clare Stevenson

Colombo

Coronation of the Emperor of Brazil

COVID-19 pandemic

Cult of personality

Danzig Street shooting

Deaths in 2022

Dreaming of You (Selena album)

Early Muslim conquests

Ellaisa Marquis

Encyclopedia

English language

File:Coronation of dom pedro II (cropped).jpg

File:Main image deep field smacs0723.png

File:Philemon corniculatus - Glen Davis.jpg

File:Pooja Sharma and award (cropped).jpg

File:Rick Monday 1973.jpg

Free content

Friarbird

Gary Moeller

Glen Davis, New South Wales

Gotabaya Rajapaksa

Guerrilla gardening

Harold Baines

Help:Introduction to Wikipedia

Help:Your first article

Hezbollah

History of the Oakland Athletics#Kansas City (1955–1967)

Honeyeater

Ibištek jedlý

International Film Music Critics Association Award for Best Original Score for a Video Game or Interactive Media

James Webb Space Telescope

Jane Austen

John Froines

José Eduardo dos Santos

July 17

July 18

July 19

Ken Griffey Jr.

Khalid ibn al-Walid

Lily Safra

List of days of the year

List of designated terrorist groups

List of first overall Major League Baseball draft picks

List of monarchs of Brazil

List of prime ministers of Italy

Long Island City

Machovka lepkavá

Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball draft

Marine Day

Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Montauk Cutoff

Monty Norman

Muhammad

Muslim conquest of Persia#First invasion of Mesopotamia (633)

Muslim conquest of the Levant

Nara, Nara

NASA

Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War)

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

New Guinea

Noisy friarbird

Oey Tiang Tjoei

Old Cathedral of Rio de Janeiro

Paper Mario: Color Splash

Passerine

Pedro II of Brazil

Pennatomys nivalis

Pittsburgh Pirates

Pooja Sharma (entrepreneur)

Portal:Current events

Povojník batatový

Priyanka Chopra

Ranil Wickremesinghe

Rashard Anderson

Rashidun Caliphate

Reďkev siata pravá

Rick Monday

Ridda Wars

Second Spanish Republic

Selena

Shinzo Abe

Shot put

Six-Bid Solo

Social media

Spanish Civil War

Spanish coup of July 1936

Tejano music

Template:POTD/2022-07-15

Template:POTD/2022-07-16

Template:POTD/2022-07-17

Template talk:Did you know

Umar

User:JJ Harrison

WAQI

Webb's First Deep Field

Wikimedia Foundation

Wikipedia

Wikipedia:Community portal

Wikipedia:Contents/Portals

Wikipedia:Featured articles

Wikipedia:Featured lists

Wikipedia:Featured pictures

Wikipedia:Featured picture candidates

Wikipedia:Help desk

Wikipedia:In the news/Candidates

Wikipedia:News

Wikipedia:Picture of the day

Wikipedia:Picture of the day/Archive

Wikipedia:Recent additions

Wikipedia:Reference desk

Wikipedia:Selected anniversaries/July

Wikipedia:Teahouse

Wikipedia:Today's featured article/July 2022

Wikipedia:Today's featured list/July 2022

Wikipedia:Village pump

World Fantasy Special Award—Professional

Zelenina

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk