A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Tone is the use of pitch in language to distinguish lexical or grammatical meaning—that is, to distinguish or to inflect words.[1] All oral languages use pitch to express emotional and other para-linguistic information and to convey emphasis, contrast and other such features in what is called intonation, but not all languages use tones to distinguish words or their inflections, analogously to consonants and vowels. Languages that have this feature are called tonal languages; the distinctive tone patterns of such a language are sometimes called tonemes,[2] by analogy with phoneme. Tonal languages are common in East and Southeast Asia, Africa, the Americas and the Pacific.[1]

Tonal languages are different from pitch-accent languages in that tonal languages can have each syllable with an independent tone whilst pitch-accent languages may have one syllable in a word or morpheme that is more prominent than the others.

Mechanics

Most languages use pitch as intonation to convey prosody and pragmatics, but this does not make them tonal languages.[3] In tonal languages, each syllable has an inherent pitch contour, and thus minimal pairs (or larger minimal sets) exist between syllables with the same segmental features (consonants and vowels) but different tones. Vietnamese and Chinese have heavily studied tone systems, as well as amongst their various dialects.

Below is a table of the six Vietnamese tones and their corresponding tone accent or diacritics:

Tone name Tone ID Vni/telex/Viqr Description Chao Tone Contour Diacritic Example Northern Southern ngang "flat" A1 mid level ˧ (33) or ˦ (44) ◌ ma huyền "deep" A2 2 / f / ` low falling (breathy) ˧˩ (31) or ˨˩ (21) ◌̀ mà sắc "sharp" B1 1 / s / ' mid rising, tense ˧˥ (35) or ˦˥ (45) ◌́ má nặng "heavy" B2 5 / j / . mid falling, glottalized, heavy ˧ˀ˨ʔ (3ˀ2ʔ) or ˧ˀ˩ʔ (3ˀ1ʔ) ˩˨ (12) or ˨˩˨ (212) ़ mạ hỏi "asking" C1 3 / r / ? mid falling(-rising), emphasis ˧˩˧ (313) or ˧˨˧ (323) or ˧˩ (31) ˧˨˦ (324) or ˨˩˦ (214) ◌̉ mả ngã "tumbling" C2 4 / x / ~ mid rising, glottalized ˧ˀ˥ (3ˀ5) or ˦ˀ˥ (4ˀ5) ◌̃ mã

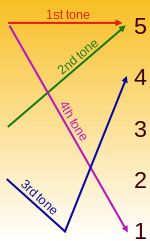

Mandarin Chinese, which has five tones, transcribed by letters with diacritics over vowels:

- A high level tone: /á/ (pinyin ⟨ā⟩)

- A tone starting with mid pitch and rising to a high pitch: /ǎ/ (pinyin ⟨á⟩)

- A low tone with a slight fall (if there is no following syllable, it may start with a dip then rise to a high pitch): /à/ (pinyin ⟨ǎ⟩)

- A short, sharply falling tone, starting high and falling to the bottom of the speaker's vocal range: /â/ (pinyin ⟨à⟩)

- A neutral tone, with no specific contour, used on weak syllables; its pitch depends chiefly on the tone of the preceding syllable.

These tones combine with a syllable such as ma to produce different words. A minimal set based on ma are, in pinyin transcription:

- mā (媽/妈) 'mother'

- má (麻/麻) 'hemp'

- mǎ (馬/马) 'horse'

- mà (罵/骂) 'scold'

- ma (嗎/吗) (an interrogative particle)

These may be combined into a tongue-twister:

- Simplified: 妈妈骂马的麻吗?

- Traditional: 媽媽罵馬的麻嗎?

- Pinyin: Māma mà mǎde má ma?

- IPA /máma mâ màtə mǎ ma/

- Translation: 'Is mom scolding the horse's hemp?'

See also One-syllable article.

A well-known tongue-twister in Standard Thai is:

- ไหมใหม่ไหม้มั้ย.

- IPA: /mǎi̯ mài̯ mâi̯ mái̯/

- Translation: 'Does new silk burn?'[a]

A Vietnamese tongue twister:

- Bấy nay bây bầy bảy bẫy bậy.

- IPA:

- Translation: 'Recently, you've been setting up the seven traps incorrectly.'

A Cantonese tongue twister:

- 一人因一日引一刃一印而忍

- Jyutping: jat1 jan4 jan1 jat1 jat6 jan5 jat1 jan6 jat1 jan3 ji4 jan2

- IPA:

- Translation: 'One person endures a day with one knife and one print.'

Tone is most frequently manifested on vowels, but in most tonal languages where voiced syllabic consonants occur they will bear tone as well. This is especially common with syllabic nasals, for example in many Bantu and Kru languages, but also occurs in Serbo-Croatian. It is also possible for lexically contrastive pitch (or tone) to span entire words or morphemes instead of manifesting on the syllable nucleus (vowels), which is the case in Punjabi.[4]

Tones can interact in complex ways through a process known as tone sandhi.

Phonation

In a number of East Asian languages, tonal differences are closely intertwined with phonation differences. In Vietnamese, for example, the ngã and sắc tones are both high-rising but the former is distinguished by having glottalization in the middle. Similarly, the nặng and huyền tones are both low-falling, but the nặng tone is shorter and pronounced with creaky voice at the end, while the huyền tone is longer and often has breathy voice. In some languages, such as Burmese, pitch and phonation are so closely intertwined that the two are combined in a single phonological system, where neither can be considered without the other. The distinctions of such systems are termed registers. The tone register here should not be confused with register tone described in the next section.

Phonation type

Gordon and Ladefoged established a continuum of phonation, where several types can be identified.[5]

Relationship with tone

Kuang identified two types of phonation: pitch-dependent and pitch-independent.[6] Contrast of tones has long been thought of as differences in pitch height. However, several studies pointed out that tone is actually multidimensional. Contour, duration, and phonation may all contribute to the differentiation of tones. Investigations from the 2010s using perceptual experiments seem to suggest phonation counts as a perceptual cue.[6][7][8]

Tone and pitch accent

Many languages use tone in a more limited way. In Japanese, fewer than half of the words have a drop in pitch; words contrast according to which syllable this drop follows. Such minimal systems are sometimes called pitch accent since they are reminiscent of stress accent languages, which typically allow one principal stressed syllable per word. However, there is debate over the definition of pitch accent and whether a coherent definition is even possible.[9]

Tone and intonation

Both lexical or grammatical tone and prosodic intonation are cued by changes in pitch, as well as sometimes by changes in phonation. Lexical tone coexists with intonation, with the lexical changes of pitch like waves superimposed on larger swells. For example, Luksaneeyanawin (1993) describes three intonational patterns in Thai: falling (with semantics of "finality, closedness, and definiteness"), rising ("non-finality, openness and non-definiteness") and "convoluted" (contrariness, conflict and emphasis). The phonetic realization of these intonational patterns superimposed on the five lexical tones of Thai (in citation form) are as follows:[10]

| Falling intonation |

Rising intonation |

Convoluted intonation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High level tone | ˦˥˦ | ˥ | ˦˥˨ |

| Mid level tone | ˧˨ | ˦ | ˧˦˨ |

| Low level tone | ˨˩ | ˧ | ˧˧˦ |

| Falling tone | ˦˧˨, ˦˦˨ | ˦˦˧, ˥˥˦ | ˦˥˨ |

| Rising tone | ˩˩˦ | ˧˧˦ | ˨˩˦ |

With convoluted intonation, it appears that high and falling tone conflate, while the low tone with convoluted intonation has the same contour as rising tone with rising intonation.

Tonal polarity

Languages with simple tone systems or pitch accent may have one or two syllables specified for tone, with the rest of the word taking a default tone. Such languages differ in which tone is marked and which is the default. In Navajo, for example, syllables have a low tone by default, whereas marked syllables have high tone. In the related language Sekani, however, the default is high tone, and marked syllables have low tone.[11] There are parallels with stress: English stressed syllables have a higher pitch than unstressed syllables.[12]

Types

Register tones and contour tones

In many Bantu languages, tones are distinguished by their pitch level relative to each other. In multisyllable words, a single tone may be carried by the entire word rather than a different tone on each syllable. Often, grammatical information, such as past versus present, "I" versus "you", or positive versus negative, is conveyed solely by tone.

In the most widely spoken tonal language, Mandarin Chinese, tones are distinguished by their distinctive shape, known as contour, with each tone having a different internal pattern of rising and falling pitch.[13] Many words, especially monosyllabic ones, are differentiated solely by tone. In a multisyllabic word, each syllable often carries its own tone. Unlike in Bantu systems, tone plays little role in the grammar of modern standard Chinese, though the tones descend from features in Old Chinese that had morphological significance (such as changing a verb to a noun or vice versa).

Most tonal languages have a combination of register and contour tones. Tone is typical of languages including Kra–Dai, Vietic, Sino-Tibetan, Afroasiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo and Nilo-Saharan languages. Most tonal languages combine both register and contour tones, such as Cantonese, which produces three varieties of contour tone at three different pitch levels,[14] and the Omotic (Afroasiatic) language Bench, which employs five level tones and one or two rising tones across levels.[15]

Most varieties of Chinese use contour tones, where the distinguishing feature of the tones are their shifts in pitch (that is, the pitch is a contour), such as rising, falling, dipping, or level. Most Bantu languages (except northwestern Bantu) on the other hand, have simpler tone systems usually with high, low and one or two contour tone (usually in long vowels). In such systems there is a default tone, usually low in a two-tone system or mid in a three-tone system, that is more common and less salient than other tones. There are also languages that combine relative-pitch and contour tones, such as many Kru languages and other Niger-Congo languages of West Africa.

Falling tones tend to fall further than rising tones rise; high–low tones are common, whereas low–high tones are quite rare. A language with contour tones will also generally have as many or more falling tones than rising tones. However, exceptions are not unheard of; Mpi, for example, has three level and three rising tones, but no falling tones.

Word tones and syllable tones

Another difference between tonal languages is whether the tones apply independently to each syllable or to the word as a whole. In Cantonese, Thai, and Kru languages, each syllable may have a tone, whereas in Shanghainese,[citation needed] Swedish, Norwegian and many Bantu languages, the contour of each tone operates at the word level. That is, a trisyllabic word in a three-tone syllable-tone language has many more tonal possibilities (3 × 3 × 3 = 27) than a monosyllabic word (3), but there is no such difference in a word-tone language. For example, Shanghainese has two contrastive (phonemic) tones no matter how many syllables are in a word.[citation needed] Many languages described as having pitch accent are word-tone languages.

Tone sandhi is an intermediate situation, as tones are carried by individual syllables, but affect each other so that they are not independent of each other. For example, a number of Mandarin Chinese suffixes and grammatical particles have what is called (when describing Mandarin Chinese) a "neutral" tone, which has no independent existence. If a syllable with a neutral tone is added to a syllable with a full tone, the pitch contour of the resulting word is entirely determined by that other syllable:

| Tone in isolation | Tone pattern with added neutral tone |

Example | Pinyin | English meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| high ˥ | ˥꜋ | 玻璃 | bōli | glass |

| rising ˧˥ | ˧˥꜊ | 伯伯 | bóbo | elder uncle |

| dipping ˨˩˦ | ˨˩꜉ | 喇叭 | lǎba | horn |

| falling ˥˩ | ˥˩꜌ | 兔子 | tùzi | rabbit |

After high level and high rising tones, the neutral syllable has an independent pitch that looks like a mid-register tone – the default tone in most register-tone languages. However, after a falling tone it takes on a low pitch; the contour tone remains on the first syllable, but the pitch of the second syllable matches where the contour leaves off. And after a low-dipping tone, the contour spreads to the second syllable: the contour remains the same (˨˩˦) whether the word has one syllable or two. In other words, the tone is now the property of the word, not the syllable. Shanghainese has taken this pattern to its extreme, as the pitches of all syllables are determined by the tone before them, so that only the tone of the initial syllable of a word is distinctive.

Lexical tones and grammatical tones

Lexical tones are used to distinguish lexical meanings. Grammatical tones, on the other hand, change the grammatical categories.[16] To some authors, the term includes both inflectional and derivational morphology.[17] Tian described a grammatical tone, the induced creaky tone, in Burmese.[18]

Number of tones

Languages may distinguish up to five levels of pitch, though the Chori language of Nigeria is described as distinguishing six surface tone registers.[19] Since tone contours may involve up to two shifts in pitch, there are theoretically 5 × 5 × 5 = 125 distinct tones for a language with five registers. However, the most that are actually used in a language is a tenth of that number.

Several Kam–Sui languages of southern China have nine contrastive tones, including contour tones. For example, the Kam language has 9 tones: 3 more-or-less fixed tones (high, mid and low); 4 unidirectional tones (high and low rising, high and low falling); and 2 bidirectional tones (dipping and peaking). This assumes that checked syllables are not counted as having additional tones, as they traditionally are in China. For example, in the traditional reckoning, the Kam language has 15 tones, but 6 occur only in syllables closed with the voiceless stop consonants /p/, /t/ or /k/ and the other 9 occur only in syllables not ending in one of these sounds.

Preliminary work on the Wobe language (part of the Wee continuum) of Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire, the Ticuna language of the Amazon and the Chatino languages of southern Mexico suggests that some dialects may distinguish as many as fourteen tones or more. The Guere language, Dan language and Mano language of Liberia and Ivory Coast have around 10 tones, give or take. The Oto-Manguean languages of Mexico have a huge number of tones as well. The most complex tonal systems are actually found in Africa and the Americas, not east Asia.

Tonal change

Tone terracing

Tones are realized as pitch only in a relative sense. "High tone" and "low tone" are only meaningful relative to the speaker's vocal range and in comparing one syllable to the next, rather than as a contrast of absolute pitch such as one finds in music. As a result, when one combines tone with sentence prosody, the absolute pitch of a high tone at the end of a prosodic unit may be lower than that of a low tone at the beginning of the unit, because of the universal tendency (in both tonal and non-tonal languages) for pitch to decrease with time in a process called downdrift.

Tones may affect each other just as consonants and vowels do. In many register-tone languages, low tones may cause a downstep in following high or mid tones; the effect is such that even while the low tones remain at the lower end of the speaker's vocal range (which is itself descending due to downdrift), the high tones drop incrementally like steps in a stairway or terraced rice fields, until finally the tones merge and the system has to be reset. This effect is called tone terracing.

Sometimes a tone may remain as the sole realization of a grammatical particle after the original consonant and vowel disappear, so it can only be heard by its effect on other tones. It may cause downstep, or it may combine with other tones to form contours. These are called floating tones.

Tone sandhi

In many contour-tone languages, one tone may affect the shape of an adjacent tone. The affected tone may become something new, a tone that only occurs in such situations, or it may be changed into a different existing tone. This is called tone sandhi. In Mandarin Chinese, for example, a dipping tone between two other tones is reduced to a simple low tone, which otherwise does not occur in Mandarin Chinese, whereas if two dipping tones occur in a row, the first becomes a rising tone, indistinguishable from other rising tones in the language. For example, the words 很 ('very') and 好 ('good') produce the phrase 很好 ('very good'). The two transcriptions may be conflated with reversed tone letters as .

Right- and left-dominant sandhi

Tone sandhi in Sinitic languages can be classified with a left-dominant or right-dominant system. In a language of the right-dominant system, the right-most syllable of a word retains its citation tone (i.e., the tone in its isolation form). All the other syllables of the word must take their sandhi form.[20][21] Taiwanese Southern Min is known for its complex sandhi system. Example: 鹹kiam5 'salty'; 酸sng1 'sour'; 甜tinn1 'sweet'; 鹹酸甜kiam7 sng7 tinn1 'candied fruit'. In this example, only the last syllable remains unchanged. Subscripted numbers represent the changed tone.

Tone changeedit

Tone change must be distinguished from tone sandhi. Tone sandhi is a compulsory change that occurs when certain tones are juxtaposed. Tone change, however, is a morphologically conditioned alternation and is used as an inflectional or a derivational strategy.[22] Lien indicated that causative verbs in modern Southern Min are expressed with tonal alternation, and that tonal alternation may come from earlier affixes. Examples: 長 tng5 'long' vs. tng2 'grow'; 斷 tng7 'break' vs. tng2 'cause to break'.[23] Also, 毒 in Taiwanese Southern Min has two pronunciations: to̍k (entering tone) means 'poison' or 'poisonous', while thāu (departing tone) means 'to kill with poison'.[24] The same usage can be found in Min, Yue, and Hakka.[25]

Neutralisationedit

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (September 2020) |

Uses of toneedit

In East Asia, tone is typically lexical. That is, tone is used to distinguish words which would otherwise be homonyms. This is characteristic of heavily tonal languages such as Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, and Hmong.

However, in many African languages, especially in the Niger–Congo family, tone can be both lexical and grammatical. In the Kru languages, a combination of these patterns is found: nouns tend to have complex tone systems but are not much affected by grammatical inflections, whereas verbs tend to have simple tone systems, which are inflected to indicate tense and mood, person, and polarity, so that tone may be the only distinguishing feature between "you went" and "I won't go".

In colloquial Yoruba, especially when spoken quickly, vowels may assimilate to each other, and consonants elide so much that much of the lexical and grammatical information is carried by tone.[citation needed] In languages of West Africa such as Yoruba, people may even communicate with so-called "talking drums", which are modulated to imitate the tones of the language, or by whistling the tones of speech.[citation needed]

Note that tonal languages are not distributed evenly across the same range as non-tonal languages.[26] Instead, the majority of tone languages belong to the Niger-Congo, Sino-Tibetan and Vietic groups, which are then composed by a large majority of tone languages and dominate a single region. Only in limited locations (South Africa, New Guinea, Mexico, Brazil and a few others) do tone languages occur as individual members or small clusters within a non-tone dominated area. In some locations, like Central America, it may represent no more than an incidental effect of which languages were included when one examines the distribution; for groups like Khoi-San in Southern Africa and Papuan languages, whole families of languages possess tonality but simply have relatively few members, and for some North American tone languages, multiple independent origins are suspected.

If generally considering only complex-tone vs. no-tone, it might be concluded that tone is almost always an ancient feature within a language family that is highly conserved among members. However, when considered in addition to "simple" tone systems that include only two tones, tone, as a whole, appears to be more labile, appearing several times within Indo-European languages, several times in American languages, and several times in Papuan families.[26] That may indicate that rather than a trait unique to some language families, tone is a latent feature of most language families that may more easily arise and disappear as languages change over time.[27]

A 2015 study by Caleb Everett argued that tonal languages are more common in hot and humid climates, which make them easier to pronounce, even when considering familial relationships. If the conclusions of Everett's work are sound, this is perhaps the first known case of influence of the environment on the structure of the languages spoken in it.[28][29] The proposed relationship between climate and tone is controversial, and logical and statistical issues have been raised by various scholars.[30][31][32]

Tone and inflectionedit

Tone has long been viewed as a phonological system. It was not until recent years that tone was found to play a role in inflectional morphology. Palancar and Léonard (2016)[33] provided an example with Tlatepuzco Chinantec (an Oto-Manguean language spoken in Southern Mexico), where tones are able to distinguish mood, person, and number:

| 1 SG | 1 PL | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completive | húʔ˩ | húʔ˩˥ | húʔ˩ | húʔ˧ |

| Incompletive | húʔ˩˧ | húʔ˩˧ | húʔ˩˧ | húʔ˧ |

| Irrealis | húʔ˩˥ | húʔ˩˥ | húʔ˩˥ | húʔ˧ |

In Iau language (the most tonally complex Lakes Plain language, predominantly monosyllabic), nouns have an inherent tone (e.g. be˧ 'fire' but be˦˧ 'flower'), but verbs don't have any inherent tone. For verbs, a tone is used to mark aspect. The first work that mentioned this was published in 1986.[34] Example paradigms:[35]