A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

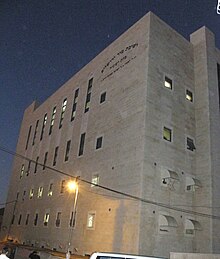

A yeshiva or jeshibah (/jəˈʃiːvə/; Hebrew: ישיבה, lit. 'sitting'; pl. ישיבות, yeshivot or yeshivos) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are studied in parallel. The studying is usually done through daily shiurim (lectures or classes) as well as in study pairs called chavrusas (Aramaic for 'friendship' or 'companionship').[1] Chavrusa-style learning is one of the unique features of the yeshiva.

In the United States and Israel, different levels of yeshiva education have different names. In the U.S., elementary-school students enroll in a cheder, post-bar mitzvah-age students learn in a mesivta, and undergraduate-level students learn in a beit midrash or yeshiva gedola (Hebrew: ישיבה גדולה, lit. 'large yeshiva' or 'great yeshiva'). In Israel, elementary-school students enroll in a Talmud Torah or cheder, post-bar mitzvah-age students learn in a yeshiva ketana (Hebrew: ישיבה קטנה, lit. 'small yeshiva' or 'minor yeshiva'), and high-school-age students learn in a yeshiva gedola.[2][3] A kollel is a yeshiva for married men, in which it is common to pay a token stipend to its students. Students of Lithuanian and Hasidic yeshivot gedolot (plural of yeshiva gedola) usually learn in yeshiva until they get married.

Historically, yeshivas were for men only. Today, all non-Orthodox yeshivas are open to women. Although there are separate schools for Orthodox women and girls,[4] (midrasha or "seminary") these do not follow the same structure or curriculum as the traditional yeshiva for boys and men.

Etymology

Alternate spellings and names include yeshivah; metivta and mesivta (Imperial Aramaic: מתיבתא methivta); beth midrash; Talmudical academy, rabbinical academy and rabbinical school. The word yeshiva is applied to the activity of learning in class, and hence to a learning "session."[5]

The transference in meaning of the term from the learning session to the institution itself appears to have occurred by the time of the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, Sura and Pumbedita, which were known as shte ha-yeshivot (the two colleges).

History

Origins

The Mishnah tractate Megillah contains the law that a town can only be called a city if it supports ten men (batlanim) to make up the required quorum for communal prayers. Similarly, every beth din ('house of judgement') was attended by a number of pupils up to three times the size of the court (Mishnah, tractate Sanhedrin). According to the Talmud,[6] adults generally took two months off every year to study. These being Elul and Adar the months preceding the pilgrimage festivals of Sukkot and Pesach, called Yarḥei Kalla (Aramaic for 'Months of Kallah'). The rest of the year, they worked.

Geonic period

The Geonic period takes its name from Gaon, the title given to the heads of the three yeshivas which existed from the third to the thirteenth century. The Geonim acted as the principals of their individual yeshivot, and as spiritual leaders and high judges for the wider communities tied to them. The yeshiva conducted all official business in the name of its Gaon, and all correspondence to or from the yeshiva was addressed directly to the Gaon.

Throughout the Geonic Period there were three yeshivot, each named for the cities in which they were located: Jerusalem, Sura, and Pumbedita; the yeshiva of Jerusalem would later relocate to Cairo, and the yeshivot of Sura and Pumbedita to Baghdad, but retain their original names. Each Jewish community would associate itself with one of the three yeshivot; Jews living around the Mediterranean typically followed the yeshiva in Jerusalem, while those living in the Arabian Peninsula and modern-day Iraq and Iran typically followed one of the two yeshivot in Baghdad. There was no requirement for this, and each community could choose to associate with any of the yeshivot.

The yeshiva served as the highest educational institution for the Rabbis of this period. In addition to this, the yeshiva wielded great power as the principal body for interpreting Jewish law. The community regarded the Gaon of a yeshiva as the highest judge on all matters of Jewish law. Each yeshiva ruled differently on matters of ritual and law; the other yeshivot accepted these divisions, and all three ranked as equally orthodox. The yeshiva also served as an administrative authority, in conjunction with local communities, by appointing members to serve as the head of local congregations. These heads of a congregation served as a link between the congregation and the larger yeshiva it was attached to. These leaders would also submit questions to the yeshiva to obtain final rulings on issues of dogma, ritual, or law. Each congregation was expected to follow only one yeshiva to prevent conflict with different rulings issued by different yeshivot.

The yeshivot were financially supported by a number of means, including fixed voluntary, annual contributions; these contributions being collected and handled by local leaders appointed by the yeshiva. Private gifts and donations from individuals were also common, especially during holidays, consisting of money or goods.

The yeshiva of Jerusalem was finally forced into exile in Cairo in 1127, and eventually dispersed entirely. Likewise, the yeshivot of Sura and Pumbedita were dispersed following the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. After this education in Jewish religious studies became the responsibility of individual synagogues. No organization ever came to replace the three great yeshivot of Jerusalem, Sura and Pumbedita.[7]

To 19th century

After the Geonic Period Jews established more Yeshiva academies in Europe and in Northern Africa, including the Kairuan yeshiva in Tunisia (Hebrew: ישיבת קאירואן) that was established by Chushiel Ben Elchanan (Hebrew: חושיאל בן אלחנן) in 974.[8]

Traditionally, every town rabbi had the right to maintain a number of full or part-time pupils in the town's beth midrash (study hall), which was usually adjacent to the synagogue. Their cost of living was covered by community taxation. After a number of years, the students who received semikha (rabbinical ordination) would either take up a vacant rabbinical position elsewhere or join the workforce.

Lithuanian

Organised Torah study was revolutionised by Chaim Volozhin, an influential 18th-century Lithuanian leader of Judaism and disciple of the Vilna Gaon. In his view, the traditional arrangement did not cater to those looking for more intensive study.

With the support of his teacher, Volozhin gathered interested students and started a yeshiva in the town of Valozhyn, located in modern-day Belarus. The Volozhin yeshiva was closed some 60 years later in 1892 following the Russian government's demands for the introduction of certain secular studies.[9] Thereafter, a number of yeshivot opened in other towns and cities, most notably Slabodka, Panevėžys, Mir, Brisk, and Telz. Many prominent contemporary yeshivot in the United States and Israel are continuations of these institutions, and often bear the same name.

In the 19th century, Israel Salanter initiated the Mussar movement in non-Hasidic Lithuanian Jewry, which sought to encourage yeshiva students and the wider community to spend regular times devoted to the study of Jewish ethical works. Concerned by the new social and religious changes of the Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment), and other emerging political ideologies (such as Zionism) that often opposed traditional Judaism, the masters of Mussar saw a need to augment Talmudic study with more personal works. These comprised earlier classic Jewish ethical texts (mussar literature), as well as a new literature for the movement.[10] After early opposition, the Lithuanian yeshiva world saw the need for this new component in their curriculum, and set aside times for individual mussar study and mussar talks ("mussar shmues"). A mashgiach ruchani (spiritual mentor) encouraged the personal development of each student. To some degree, this Lithuanian movement arose in response, and as an alternative, to the separate mystical study of the Hasidic Judaism world. Hasidism began in the previous century within traditional Jewish life in Ukraine, and spread to Hungary, Poland and Russia. As the 19th century brought upheavals and threats to traditional Judaism, the Mussar teachers saw the benefit of the new spiritual focus in Hasidism, and developed their alternative ethical approach to spirituality.

Some variety developed within Lithuanian yeshivas to methods of studying Talmud and mussar, for example whether the emphasis would be placed on beki'ut (breadth) or iyyun (depth). Pilpul, a type of in-depth analytical and casuistic argumentation popular from the 16th to 18th centuries that was traditionally reserved for investigative Talmudic study, was not always given a place. The new analytical approach of the Brisker method, developed by Chaim Soloveitchik, has become widely popular. Other approaches include those of Mir, Chofetz Chaim, and Telz. In mussar, different schools developed, such as Slabodka and Novhardok, though today, a decline in devoted spiritual self-development from its earlier intensity has to some extent levelled out the differences.

Hasidic

With the success of the yeshiva institution in Lithuanian Jewry, the Hasidic world developed their own yeshivas, in their areas of Eastern Europe. These comprised the traditional Jewish focus on Talmudic literature that is central to Rabbinic Judaism, augmented by study of Hasidic philosophy (Hasidism). Examples of these Hasidic yeshivas are the Chabad Lubavitch yeshiva system of Tomchei Temimim, founded by Sholom Dovber Schneersohn in Russia in 1897, and the Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva established in Poland in 1930 by Meir Shapiro, who is renowned in both Hasidic and Lithuanian Jewish circles for initiating the Daf Yomi daily cycle of Talmud study. (For contemporary yeshivas, see, for example, under Satmar, Belz, Bobov, Breslov and Pupa.)

In many Hasidic yeshivas, study of Hasidic texts is a secondary activity, similar to the additional mussar curriculum in Lithuanian yeshivas. These paths see Hasidism as a means to the end of inspiring emotional devekut (spiritual attachment to God) and mystical enthusiasm. In this context, the personal pilgrimage of a Hasid to his Rebbe is a central feature of spiritual life, in order to awaken spiritual fervour. Often, such paths will reserve the Shabbat in the yeshiva for the sweeter teachings of the classic texts of Hasidism.

In contrast, Chabad and Breslov, in their different ways, place daily study of their dynasties' Hasidic texts in central focus; see below. Illustrative of this is Sholom Dovber Schneersohn's wish in establishing the Chabad yeshiva system, that the students should spend a part of the daily curriculum learning Chabad Hasidic texts "with pilpul". The idea to learn Hasidic mystical texts with similar logical profundity, derives from the unique approach in the works of the Rebbes of Chabad, initiated by its founder Schneur Zalman of Liadi, to systematically investigate and articulate the "Torah of the Baal Shem Tov" in intellectual forms. Further illustrative of this is the differentiation in Chabad thought (such as the "Tract on Ecstasy" by Dovber Schneuri) between general Hasidism's emphasis on emotional enthusiasm and the Chabad ideal of intellectually reserved ecstasy. In the Breslov movement, in contrast, the daily study of works from the imaginative, creative radicalism of Nachman of Breslov awakens the necessary soulfulness with which to approach other Jewish study and observance.

Sephardi

- See: Category:Sephardic yeshivas, as well the more complete, קטגוריה:ישיבות ספרדיות

Although the yeshiva as an institution is in some ways a continuation of the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, large scale educational institutions of this kind were not characteristic of the North African and Middle Eastern Sephardi Jewish world in pre-modern times: education typically took place in a more informal setting in the synagogue or in the entourage of a famous rabbi. In medieval Spain, and immediately following the expulsion in 1492, there were some schools which combined Jewish studies with sciences such as logic and astronomy, similar to the contemporary Islamic madrasas. In 19th century Jerusalem, a college was typically an endowment for supporting ten adult scholars rather than an educational institution in the modern sense; towards the end of the century a school for orphans was founded providing for some rabbinic studies.[11] Early educational institutions on the European model were Midrash Bet Zilkha founded in 1870s Iraq and Porat Yosef Yeshiva founded in Jerusalem in 1914. Also notable is the Bet El yeshiva founded in 1737 in Jerusalem for advanced Kabbalistic studies. Later Sephardic yeshivot are usually on the model either of Porat Yosef or of the Ashkenazi institutions.

The Sephardic world has traditionally placed the study of Kabbalah (esoteric Jewish mysticism) in a more mainstream position than in the European Ashkenazi world. This difference of emphasis arose as a result of the Sabbatean heresy in the 17th century, that suppressed widespread study of Kabbalah in Europe in favour of Rabbinic Talmudic study. In Eastern European Lithuanian life, Kabbalah was reserved for an intellectual elite, while the mystical revival of Hasidism articulated Kabbalistic theology through Hasidic thought. These factors did not affect the Sephardi Jewish world, which retained a wider connection to Kabbalah in its traditionally observant communities. With the establishment of Sephardi yeshivas in Israel after the immigration of the Arabic Jewish communities there, some Sephardi yeshivas incorporated study of more accessible Kabbalistic texts into their curriculum. The European prescriptions to restrict advanced Kabbalistic study to mature and elite students also influence the choice of texts in such yeshivas.

19th century to present

Conservative movement

In 1854, the Jewish Theological Seminary of Breslau was founded. It was headed by Zecharias Frankel, and was viewed as the first educational institution associated with "positive-historical Judaism", the predecessor of Conservative Judaism. In subsequent years, Conservative Judaism established a number of other institutions of higher learning (such as the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York City) that emulate the style of traditional yeshivas in significant ways. Many do not officially refer to themselves as "yeshivas" (one exception is the Conservative Yeshiva in Jerusalem), and all are open to both women and men, who study in the same classrooms and follow the same curriculum. Students may study part-time, as in a kollel, or full-time, and they may study lishmah (for the sake of studying itself) or towards earning rabbinic ordination.

Nondenominational or mixed

Non-denominational yeshivas and kollels with connections to Conservative Judaism include Yeshivat Hadar in New York, whose leaders include Rabbinical Assembly members Elie Kaunfer and Shai Held. The rabbinical school of the Academy for Jewish Religion in California is led by Conservative rabbi Mel Gottlieb. The faculty of the Academy for Jewish Religion in New York and of the Rabbinical School of Hebrew College in Newton Centre, Massachusetts also includes many Conservative rabbis.

More recently, several non-traditional, and nondenominational (also called "transdenominational" or "postdenominational") seminaries have been established.[12][13][14] These grant semikha in a shorter time, and with a modified curriculum, generally focusing on leadership and pastoral roles. These are JSLI, RSI, PRS and Ateret Tzvi. The Wolkowisk Mesifta is aimed at community professionals with significant knowledge and experience, and provides a tailored program to each candidate.

Reform and Reconstructionist seminaries

Hebrew Union College (HUC), affiliated with Reform Judaism, was founded in 1875 under the leadership of Isaac Mayer Wise in Cincinnati, Ohio. HUC later opened additional locations in New York, Los Angeles, and Jerusalem. It is a rabbinical seminary or college mostly geared for the training of rabbis and clergy specifically. Similarly, the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College of Reconstructionist Judaism, founded in Pennsylvania in 1968, functions to train its future clergy. Some Reform and Reconstructionist teachers also teach at the non-denominational seminaries mentioned above. In Europe, Reform Judaism trains rabbis at Leo Baeck College in London, UK and Abraham Geiger Kolleg in Potsdam, Germany. None of these institutions describes itself as a "yeshiva".

Contemporary Orthodox

World War II and the Holocaust brought the yeshivot of Eastern and Central Europe to an end; although many scholars and rabbinic students who survived the war established yeshivot in a number of Western countries.[17] The Yeshiva of Nitra was the last surviving in occupied Europe. Many students and faculty of the Mir Yeshiva were able to escape to Siberia, with the Yeshiva ultimately continuing to operate in Shanghai; see Yeshivas in World War II.

From the mid-20th century[17] the greatest number of yeshivot, and the most important were centered in Israel and in the U.S.; they were also found in many other Western countries, prominent examples being Gateshead Yeshiva in England (one of the descendants of Novardok) and the Yeshiva of Aix-les-Bains, France. The Chabad movement was particularly active in this direction,[17] establishing yeshivot also in France, North Africa, Australia, and South Africa; this "network of institutions" is known as Tomchei Temimim.

Many prominent contemporary yeshivot in the U.S. and Israel are continuations of European institutions, and often bear the same name.

Israel

Yeshivot in Israel have operated since Talmudic times,[18] as above; see Talmudic academies in Eretz Yisrael. More recent examples include the Ari Ashkenazi Synagogue (since the mid-1500s); the Bet El yeshiva (operating since 1737); and Etz Chaim Yeshiva (since 1841). Various yeshivot were established in Israel in the early 20th century: Shaar Hashamayim in 1906, Chabad's Toras Emes in 1911, Hebron Yeshiva in 1924, Sfas Emes in 1925, Lomza in 1926. After (and during) World War II, numerous other Haredi and Hasidic Yeshivot were re-established there by survivors. The Mir Yeshiva in Jerusalem – today the largest Yeshiva in the world – was established in 1944, by Rabbi Eliezer Yehuda Finkel who had traveled to Palestine to obtain visas for his students; Ponevezh similarly by Rabbi Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman; and Knesses Chizkiyahu in 1949. The leading Sephardi Yeshiva, Porat Yosef, was founded in 1914; its predecessor, Yeshivat Ohel Moed was founded in 1904. From the 1940s and onward, especially following immigration of the Arabic Jewish communities, Sephardi leaders, such as Ovadia Yosef and Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel, established various yeshivot to facilitate Torah education for Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews (and alternative to Lithuanian yeshivot).

The Haredi community has grown with time – In 2018, 12% of Israel's population was Haredi,[19] including Sephardic Haredim – supporting numerous yeshivot correspondingly. Boys and girls here attend separate schools, and proceed to higher Torah study, in a yeshiva or seminary, respectively, starting anywhere between the ages of 13 and 18; see Chinuch Atzmai and Bais Yaakov. A significant proportion of young men then remain in yeshiva until their marriage; thereafter many continue their Torah studies in a kollel. (In 2018, there were 133,000 in full-time learning .[19]) Kollel studies usually focus on deep analysis of Talmud, and those Tractates not usually covered in the standard "undergraduate" program; see § Talmud study below. Some Kollels similarly focus on halacha in total, others specifically on those topics required for Semikha (Rabbinic ordination) or Dayanut (qualification as a Rabbinic Judge). The certification in question is often conferred by the Rosh Yeshiva.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Yeshivos

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk