A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labor |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike and industrial action in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the Industrial Revolution, when mass labor became important in factories and mines. As striking became a more common practice, governments were often pushed to act (either by private business or by union workers). When government intervention occurred, it was rarely neutral or amicable. Early strikes were often deemed unlawful conspiracies or anti-competitive cartel action and many were subject to massive legal repression by state police, federal military power, and federal courts.[1] Many Western nations legalized striking under certain conditions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Strikes are sometimes used to pressure governments to change policies. Occasionally, strikes destabilize the rule of a particular political party or ruler; in such cases, strikes are often part of a broader social movement taking the form of a campaign of civil resistance. Notable examples are the 1980 Gdańsk Shipyard and the 1981 Warning Strike led by Lech Wałęsa. These strikes were significant in the long campaign of civil resistance for political change in Poland, and were an important mobilizing effort that contributed to the fall of the Iron Curtain and the end of communist party rule in Eastern Europe.[2] Another example are the strikes that followed the Kapp Putsch which were organised by the USPD and the German Communist Party that resulted in the collapse of the Putsch.

History

Origin of the term

The use of the English word "strike" to describe a work protest was first seen in 1768, when sailors, in support of demonstrations in London, "struck" or removed the topgallant sails of merchant ships at port, thus crippling the ships.[3][4][5]

Pre-industrial strikes

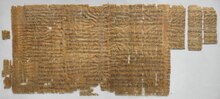

The first historically certain account of strike action was towards the end of the 20th dynasty, under Pharaoh Ramses III in ancient Egypt on 14 November in 1152 BCE. The artisans of the Royal Necropolis at Deir el-Medina walked off their jobs because they had not been paid.[6][7] The Egyptian authorities raised the wages.

The first Jewish source for the idea of a labor strike appears in the Talmud, which describes that the bakers who prepared showbread for the altar went on strike.[8]

An early predecessor of the general strike may have been the secessio plebis in ancient Rome. In The Outline of History, H. G. Wells characterized this event as "the general strike of the plebeians; the plebeians seem to have invented the strike, which now makes its first appearance in history."[9] Their first strike occurred because they "saw with indignation their friends, who had often served the state bravely in the legions, thrown into chains and reduced to slavery at the demand of patrician creditors".[9]

During and after the Industrial Revolution

The strike action only became a feature of the political landscape with the onset of the Industrial Revolution. For the first time in history, large numbers of people were members of the industrial working class; they lived in towns and cities, exchanging their labor for payment. By the 1830s, when the Chartist movement was at its peak in Britain, a true and widespread 'workers consciousness' was awakening. In 1838, a Statistical Society of London committee "used the first written questionnaire… The committee prepared and printed a list of questions 'designed to elicit the complete and impartial history of strikes.'"[10]

In 1842 the demands for fairer wages and conditions across many different industries finally exploded into the first modern general strike. After the second Chartist Petition was presented to Parliament in April 1842 and rejected, the strike began in the coal mines of Staffordshire, England, and soon spread through Britain affecting factories, cotton mills in Lancashire and coal mines from Dundee to South Wales and Cornwall.[11] Instead of being a spontaneous uprising of the mutinous masses, the strike was politically motivated and was driven by an agenda to win concessions. As much as half of the then industrial work force were on strike at its peak – over 500,000 men.[12] The local leadership marshaled a growing working class tradition to politically organize their followers to mount an articulate challenge to the capitalist, political establishment. Friedrich Engels, an observer in London at the time, wrote:

by its numbers, this class has become the most powerful in England, and woe betide the wealthy Englishmen when it becomes conscious of this fact … The English proletarian is only just becoming aware of his power, and the fruits of this awareness were the disturbances of last summer.[13]

As the 19th century progressed, strikes became a fixture of industrial relations across the industrialized world, as workers organized themselves to collectively bargain for better wages and standards with their employers. Karl Marx condemned the theory of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon criminalizing strike action in his work The Poverty of Philosophy.[14]

Recognition strikes

A recognition strike is an industrial strike implemented in order to force a particular employer or industry to recognize a trade union as the legitimate collective bargaining agent for a company's workers.[15][16][17] In 1949, their use in the United States was described as "a weapon used with varying results by labor for the last forty years or more". One example cited was the successful formation of the United Auto Workers.[18] They were more common prior to the advent of modern American labor law (including the National Labor Relations Act), which introduced processes legally compelling an employer to recognize the legitimacy of properly certified unions.[18][15]

Two examples include the U.S. Steel recognition strike of 1901, and the subsequent coal strike of 1902.[19] A 1936 study of strikes in the United States indicated that about one third of the total number of strikes between 1927 and 1928, and over 40 percent in 1929, were due to "demands for union recognition, closed shop, and protest against union discrimination and violation of union agreements".[20] A 1988 study of strike activity and unionization in non-union municipal police departments between 1972 and 1978 found that recognition strikes were carried out "primarily where bargaining laws little or no protection of bargaining rights."[21]

In 1937, there were 4,740 strikes in the United States.[22] This was the greatest strike wave in American labor history. The number of major strikes and lockouts in the U.S. fell by 97% from 381 in 1970 to 187 in 1980 to only 11 in 2010. Companies countered the threat of a strike by threatening to close or move a plant.[23][24]

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, adopted in 1967, ensures the right to strike in Article 8. The European Social Charter, adopted in 1961, also ensures the right to strike in Article 6.

The Farah Strike, 1972–1974, labeled the "strike of the century," was organized and led by Mexican American women predominantly in El Paso, Texas.[25]

Frequency and duration

Strikes are rare, in part because many workers are not covered by a collective bargaining agreement.[26] Strikes that do occur are generally fairly short in duration.[26] Labor economist John Kennan notes:

In Britain in 1926 (the year of the general strike) about 9 workdays per worker were lost due to strikes. In 1979, the loss due to strikes was a little more than one day per worker. These are the extreme cases. In the 79 years following 1926, the number of workdays lost in Britain was less than 2 hours per year per worker. In the U.S., idleness due to strikes never exceeded one half of one percent of total working days in any year during the period 1948-2005; the average loss was 0.1% per year. Similarly, in Canada over the period 1980-2005, the annual number of work days lost due to strikes never exceeded one day per worker; on average over this period lost worktime due to strikes was about one-third of a day per worker. Although the data are not readily available for a broad sample of developed countries, the pattern described above seems quite general: days lost due to strikes amount to only a fraction of a day per worker per annum, on average, exceeding one day only in a few exceptional years.[26]

Since the 1990s, strike actions have generally further declined, a phenomenon that might be attributable to lower information costs (and thus more readily available access to information on economic rents) made possible by computerization and rising personal indebtedness, which increases the cost of job loss for striking workers.[26][27][28] In the United States, the number of workers involved in major work stoppages (including strikes and, less commonly, lockouts) that involved at least a thousand workers for at least one full shift generally declined from 1973 to 2017 (coinciding with a general decrease in overall union membership), before substantially increasing in 2018 and 2019.[29] In the 2018 and 2019 period, 3.1% of union members were involved in a work stoppage each year on average, these strikes also contained more workers than ever recorded with an average of 20,000 workers participating in each major work stoppage in 2018 and 2019.[29]

By country

For the period from 1996 to 2000, the ten countries with the most strike action (measured by average number of days not worked for every 1000 employees) were as follows:[30]

| Country | Days not worked |

|---|---|

| Denmark | 296 |

| Iceland | 244 |

| Canada | 217 |

| Spain | 189 |

| Norway | 135 |

| South Korea | 95 |

| Ireland | 90 |

| Australia | 86 |

| Italy | 76 |

| France | 67 |

Variations

Most strikes are organized by labor unions during collective bargaining as a last resort. The object of collective bargaining is for the employer and the union to come to an agreement over wages, benefits, and working conditions. A collective bargaining agreement may include a clause (a contractual "no-strike clause") which prohibits the union from striking during the term of the agreement.[31] Under U.S. labor law, a strike in violation of a no-strike clause is not a protected concerted activity.[31]

The scope of a no-strike clause varies; generally, the U.S. courts and National Labor Relations Board have determined that a collective bargaining agreement's no-strike clause has the same scope as the agreement's arbitration clauses, such that "the union cannot strike over an arbitrable issue."[31] The U.S. Supreme Court held in Jacksonville Bulk Terminals Inc. v. International Longshoremen's Association (1982), a case involving the International Longshoremen's Association refusing to work with goods for export to the Soviet Union in protest against its invasion of Afghanistan, that a no-strike clause does not bar unions from refusing to work as a political protest (since that is not an "arbitrable" issue), although such activity may lead to damages for a secondary boycott.[31] Whether a no-strike clause applies to sympathy strikes depends on the context.[31] Some in the labor movement consider no-strike clauses to be an unnecessary detriment to unions in the collective bargaining process.[32]

Occasionally, workers decide to strike without the sanction of a labor union, either because the union refuses to endorse such a tactic, or because the workers involved are non-unionized. Strikes without formal union authorization are also known as wildcat strikes.

In many countries, wildcat strikes do not enjoy the same legal protections as recognized union strikes, and may result in penalties for the union members who participate, or for their union. The same often applies in the case of strikes conducted without an official ballot of the union membership, as is required in some countries such as the United Kingdom.

A strike may consist of workers refusing to attend work or picketing outside the workplace to prevent or dissuade people from working in their place or conducting business with their employer. Less frequently, workers may occupy the workplace, but refuse to work. This is known as a sit-down strike. A similar tactic is the work-in, where employees occupy the workplace but still continue work, often without pay, which attempts to show they are still useful, or that worker self-management can be successful. For instance, this occurred with factory occupations in the Biennio Rosso strikes – the "two red years" of Italy from 1919 to 1920.[citation needed]

Another unconventional tactic is work-to-rule (also known as an Italian strike, in Italian: Sciopero bianco), in which workers perform their tasks exactly as they are required to but no better. For example, workers might follow all safety regulations in such a way that it impedes their productivity or they might refuse to work overtime. Such strikes may in some cases be a form of "partial strike" or "slowdown".

During the development boom of the 1970s in Australia, the Green ban was developed by certain unions described by some as more socially conscious. This is a form of strike action taken by a trade union or other organized labor group for environmentalist or conservationist purposes. This developed from the black ban, strike action taken against a particular job or employer in order to protect the economic interests of the strikers.

United States labor law also draws a distinction, in the case of private sector employers covered by the National Labor Relations Act, between "economic" and "unfair labor practice" strikes. An employer may not fire, but may permanently replace, workers who engage in a strike over economic issues. On the other hand, employers who commit unfair labor practices (ULPs) may not replace employees who strike over them, and must fire any strikebreakers they have hired as replacements in order to reinstate the striking workers.

Strikes may be specific to a particular workplace, employer, or unit within a workplace, or they may encompass an entire industry, or every worker within a city or country. Strikes that involve all workers, or a number of large and important groups of workers, in a particular community or region are known as general strikes. Under some circumstances, strikes may take place in order to put pressure on the State or other authorities or may be a response to unsafe conditions in the workplace.

A sympathy strike is a strike action in which one group of workers refuses to cross a picket line established by another as a means of supporting the striking workers. Sympathy strikes, once the norm in the construction industry in the United States, have been made much more difficult to conduct, due to decisions of the National Labor Relations Board permitting employers to establish separate or "reserved" gates for particular trades, making it an unlawful secondary boycott for a union to establish a picket line at any gate other than the one reserved for the employer it is picketing. Still, the practice continues to occur; for example, some Teamsters contracts often protect members from disciplinary action if a member refuses to cross a picket line.[33] Sympathy strikes may be undertaken by a union as an organization, or by individual union members choosing not to cross a picket line.

A jurisdictional strike in United States labor law refers to a concerted refusal to work undertaken by a union to assert its members' right to particular job assignments and to protest the assignment of disputed work to members of another union or to unorganized workers.

A rolling strike refers to a strike where only some employees in key departments or locations go on strike. These strikes are performed in order to increase stakes as negotiations draw on and to be unpredictable to the employer. Rolling strikes also serve to conserve strike funds.

A student strike involves students (sometimes supported by faculty) refusing to attend classes. In some cases, the strike is intended to draw media attention to the institution so that the grievances that are causing the students to strike can be aired before the public; this usually damages the institution's (or government's) public image. In other cases, especially in government-supported institutions, the student strike can cause a budgetary imbalance and have actual economic repercussions for the institution.

A hunger strike is a deliberate refusal to eat. Hunger strikes are often used in prisons as a form of political protest. Like student strikes, a hunger strike aims to worsen the public image of the target.

A "sickout", or (especially by uniformed police officers) "blue flu", is a type of strike action in which the strikers call in sick. This is used in cases where laws prohibit certain employees from declaring a strike. Police, firefighters, air traffic controllers, and teachers in some U.S. states are among the groups commonly barred from striking usually by state and federal laws meant to ensure the safety or security of the general public.

Newspaper writers may withhold their names from their stories as a way to protest actions of their employer.[34]

Activists may form "flying squad" groups for strikes or other actions, a form of picketing, to disrupt the workplace or another aspect of capitalist production: supporting other strikers or unemployed workers, participating in protests against globalization, or opposing abusive landlords.[35]

Legal prohibitions

Canada

On 30 January 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that there is a constitutional right to strike.[36] In this 5–2 majority decision, Justice Rosalie Abella ruled that "long with their right to associate, speak through a bargaining representative of their choice, and bargain collectively with their employer through that representative, the right of employees to strike is vital to protecting the meaningful process of collective bargaining…" . This decision adopted the dissent by Chief Justice Brian Dickson in a 1987 Supreme Court ruling on a reference case brought by the province of Alberta (Reference Re Public Service Employee Relations Act (Alta)). The exact scope of this right to strike remains unclear.[37]

Prior to this Supreme Court decision, the federal and provincial governments had the ability to introduce "back-to-work legislation", a special law that blocks the strike action (or a lockout) from happening or continuing. Canadian governments could also have imposed binding arbitration or a new contract on the disputing parties. Back-to-work legislation was first used in 1950 during a railway strike, and as of 2012 had been used 33 times by the federal government for those parts of the economy that are regulated federally (grain handling, rail and air travel, and the postal service), and in more cases provincially. In addition, certain parts of the economy can be proclaimed "essential services" in which case all strikes are illegal.[38]

Examples include when the government of Canada passed back-to-work legislation during the 2011 Canada Post lockout and the 2012 CP Rail strike, thus effectively ending the strikes. In 2016, the government's use of back-to-work legislation during the 2011 Canada Post lockout was ruled unconstitutional, with the judge specifically referencing the Supreme Court of Canada's 2015 decision in Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v Saskatchewan.[39]

People's Republic of China and the former Soviet Union

In some Marxist–Leninist states, such as the People's Republic of China, striking was illegal and viewed as counter-revolutionary also labor strikes are considered to be taboo in most East Asian cultures. In 1976, China signed the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which guaranteed the right to unions and striking, but Chinese officials declared that they had no interest in allowing these liberties.[40] In June 2008, the municipal government in the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone introduced draft labor regulations, which a labor rights advocacy group says would, if implemented and enforced, virtually restore Chinese workers' right to strike.[41] [obsolete source]

In the Soviet Union, strikes occurred throughout the existence of the USSR, most notably in the 1930s. After World War II, they diminished both in number and in scale.[42] Trade unions in the Soviet Union served in part as a means to educate workers about the country's economic system. Vladimir Lenin referred to trade unions as "Schools of Communism".[This paragraph needs citation(s)]

France

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk