A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Ulaanbaatar

| |

|---|---|

City centre with Sükhbaatar Square Ugsarmal panel buildings built in the socialist era Naadam ceremony at the National Sports Stadium | |

| Nickname(s): УБ (UB), Нийслэл (capital), Хот (city) | |

| |

Ulaanbaatar highlighted in Mongolia | |

Location of Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia | |

| Coordinates: 47°55′13″N 106°55′02″E / 47.92028°N 106.91722°E | |

| Country | |

| Monastic center established | 1639 |

| Final location | 1778 |

| Named Ulaanbaatar | 1924 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–Manager |

| • Body | Citizens' Representatives Khural of the Capital City |

| • Governor of the Capital City and Mayor of Ulaanbaatar | Khishgeegiin Nyambaatar (MPP)[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 470.4 km2 (181.63 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,350 m (4,429 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Total | 1,672,627[1] |

| • Density | 311/km2 (807/sq mi) |

| GDP | |

| • Total | MNT 34,008 billion US$ 10.9 billion (2022) |

| • Per capita | MNT 21,692,300 US$ 6,945 (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (H) |

| Postal code | 210 xxx |

| Area code | +976 (0)11 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.810[4] – very high · 1st |

| License plate | УБ, УН |

| ISO 3166-2 | MN-1 |

| Climate | BSk |

| Website | www |

Ulaanbaatar (/ˌuːlɑːn ˈbɑːtər/; Mongolian: Улаанбаатар, pronounced [ʊˌɮaːn‿ˈbaːʰtə̆r] , lit. "Red Hero"), previously anglicized as Ulan Bator, is the capital and most populous city of Mongolia. With a population of 1.6 million, it is the coldest capital city in the world by average yearly temperature.[5] The municipality is located in north central Mongolia at an elevation of about 1,300 metres (4,300 ft) in a valley on the Tuul River. The city was founded in 1639 as a nomadic Buddhist monastic centre, changing location 28 times, and was permanently settled at its modern location in 1778.

During its early years, as Örgöö (anglicized as Urga), it became Mongolia's preeminent religious centre and seat of the Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, the spiritual head of the Gelug lineage of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia. Following the regulation of Qing-Russian trade by the Treaty of Kyakhta in 1727, a caravan route between Beijing and Kyakhta opened up, along which the city was eventually settled. With the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911, the city was a focal point for independence efforts, leading to the proclamation of the Bogd Khanate in 1911 led by the 8th Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, or Bogd Khan, and again during the communist revolution of 1921. With the proclamation of the Mongolian People's Republic in 1924, the city was officially renamed Ulaanbaatar and declared the country's capital. Modern urban planning began in the 1950s, with most of the old ger districts replaced by Soviet-style flats. In 1990, Ulaanbaatar was the site of large demonstrations that led to Mongolia's transition to democracy and a market economy. Since 1990, an influx of migrants from the rest of the country has led to an explosive growth in its population, a major portion of whom live in ger districts, which has led to harmful air pollution in winter.

Governed as an independent municipality, Ulaanbaatar is surrounded by Töv Province, whose capital Zuunmod lies 43 kilometres (27 mi) south of the city. With a population of just over 1.6 million as of December 2022[update], it contains almost half of the country's total population.[6] As the country's primate city, it serves as its cultural, industrial and financial heart and the center of its transport network.[7]

Names and etymology

The city at its establishment in 1639 was referred to as Örgöö (Mongolian: ᠥᠷᠭᠦᠭᠡ; Өргөө, lit. 'Palace'). This name was eventually adapted as Urga[8] in the West. By 1651, it began to be referred to as Nomiĭn Khüree (Mongolian: ᠨᠣᠮ ᠤᠨ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Номын хүрээ, lit. 'Khüree of Wisdom'), and by 1706 it was referred to as Ikh Khüree (Mongolian: ᠶᠡᠬᠡ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Их хүрээ, lit. 'Great Khüree'). The Chinese equivalent, Dà Kùlún (Chinese: 大庫倫, Mongolian: Да Хүрээ), was rendered into Western languages as Kulun or Kuren.

Other names include Bogdiin Khuree (Mongolian: ᠪᠣᠭᠳᠠ ᠶᠢᠨ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Богдын хүрээ, lit. 'The Bogd's Khüree'), or simply Khüree (Mongolian: ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Хүрээ, romanized: Küriye), itself a term originally referring to an enclosure or settlement.

Upon independence in 1911, with both the secular government and the Bogd Khan's palace present, the city's name was changed to Niĭslel Khüree (Mongolian: ᠨᠡᠶᠢᠰᠯᠡᠯ ᠬᠦᠷᠢᠶᠡᠨ; Нийслэл Хүрээ, lit. 'Capital Khüree').

When the city became the capital of the new Mongolian People's Republic in 1924, its name was changed to Ulaanbaatar (lit. 'Red Hero').

In the Western world, Ulaanbaatar continued to be generally known as Urga or Khuree until 1924, and afterward as Ulan Bator (a spelling derived from the Russian Улан-Батор). This form was defined two decades before the Mongolian name got its current Cyrillic spelling and transliteration (1941–1950); however, the name of the city was spelled Ulaanbaatar koto during the decade in which Mongolia used the Latin alphabet.

History

Prehistory

Human habitation at the site of Ulaanbaatar dates from the Lower Paleolithic, with a number of sites on the Bogd Khan, Buyant-Ukhaa and Songinokhairkhan mountains, revealing tools which date from 300,000 years ago to 40,000–12,000 years ago. These Upper Paleolithic people hunted mammoth and woolly rhinoceros, the bones of which are found abundantly around Ulaanbaatar.[citation needed]

Before 1639

A number of Xiongnu-era royal tombs have been discovered around Ulaanbaatar, including the tombs of Belkh Gorge near Dambadarjaalin monastery and tombs of Songinokhairkhan. Located on the banks of the Tuul River, Ulaanbaatar has been well within the sphere of Turco-Mongol nomadic empires throughout history.

Wang Khan, Toghrul of the Keraites, a Nestorian Christian monarch whom Marco Polo identified as the legendary Prester John, is said to have had his palace here (the Black Forest of the Tuul River) and forbade hunting in the holy mountain Bogd Uul. The palace is said to be where Genghis Khan stayed with Yesui Khatun before attacking the Tangut in 1226.[citation needed]

During the Mongol Empire (1206-1368) and Northern Yuan dynasty (1368-1635) the main, natural route from the capital region of Karakorum to the birthplace and tomb of the Khans in the Khentii mountain region (Ikh Khorig) passed through the area of Ulaanbaatar. The Tuul River naturally leads to the north-side of Bogd Khan Mountain, which stands out as a large island of forest positioned conspicuously at the south-western edge of the Khentii mountains. As the main gate and stopover point on the route to and from the holy Khentii mountains, the Bogd Khan Mountain saw large amounts of traffic going past it and was protected from early times. Even after the Northern Yuan period it served as the location of the annual and triannual Assembly of Nobles (Khan Uuliin Chuulgan).

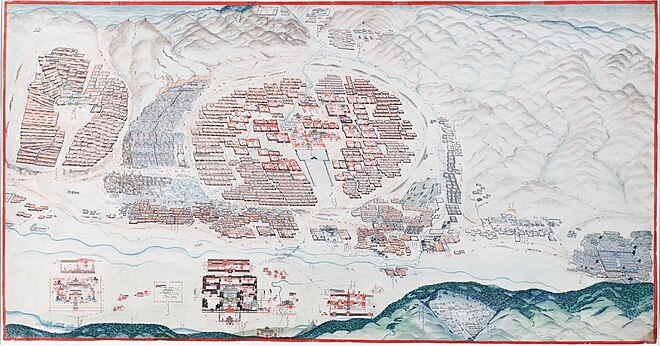

Mobile monastery

Founded in 1639 as a yurt monastery as Örgöö (lit. 'palace-yurt'), the settlement was first located at Lake Shireet Tsagaan nuur (75 kilometres (47 miles) directly east of the imperial capital Karakorum) in what is now Burd sum, Övörkhangai, around 230 kilometres (143 miles) south-west from the present site of Ulaanbaatar, and was intended by the Mongol nobles to be the seat of Zanabazar, the first Jebtsundamba Khutughtu. Zanabazar returned to Mongolia from Tibet in 1651, and founded seven aimags (monastic departments) in Urga, later establishing four more.[9]

As a mobile monastery-town, Örgöö was often moved to various places along the Selenge, Orkhon and Tuul rivers, as supply and other needs would demand. During the Dzungar wars of the late 17th century, it was even moved to Inner Mongolia.[10] As the city grew, it moved less and less.[11]

The movements of the city can be detailed as follows: Shireet Tsagaan Nuur (1639), Khoshoo Tsaidam (1640), Khentii Mountains (1654), Ogoomor (1688), Inner Mongolia (1690), Tsetserlegiin Erdene Tolgoi (1700), Daagandel (1719), Usan Seer (1720), Ikh Tamir (1722), Jargalant (1723), Eeven Gol (1724), Khujirtbulan (1729), Burgaltai (1730), Sognogor (1732), Terelj (1733), Uliastai River (1734), Khui Mandal (1736), Khuntsal (1740), Udleg (1742), Ogoomor (1743), Selbe (1747), Uliastai River (1756), Selbe (1762), Khui Mandal (1772) and Selbe (1778).[citation needed]

In 1778, the city moved from Khui Mandal and settled for good at its current location, near the confluence of the Selbe and Tuul rivers, and beneath Bogd Khan Uul, at that time also on the caravan route from Beijing to Kyakhta.[12]

One of the earliest Western mentions of Urga is the account of the Scottish traveller John Bell in 1721:

What they call the Urga is the court, or the place where the prince (Tusheet Khan) and high priest (Bogd Jebtsundamba Khutugtu) reside, who are always encamped at no great distance from one another. They have several thousand tents about them, which are removed from time to time. The Urga is much frequented by merchants from China and Russia, and other places.[13]

By Zanabazar's death in 1723, Urga was Mongolia's preeminent monastery in terms of religious authority. A council of seven of the highest-ranking lamas (Khamba Nomon Khan, Ded Khamba and five Tsorj) made most of the city's religious decisions. It had also become Outer Mongolia's commercial center. From 1733 to 1778, Urga moved around the vicinity of its present location. In 1754, the Erdene Shanzodba Yam ^ of Urga was given authority to supervise the administrative affairs of the Bogd's subjects. It also served as the city's chief judicial court. In 1758, the Qianlong Emperor appointed the Khalkha Vice General Sanzaidorj as the first Mongol amban of Urga, with full authority to "oversee the Khuree and administer well all the Khutugtu's subjects".[14]

In 1761, a second amban was appointed for the same purpose, a Manchu one. A quarter-century later, in 1786, a decree issued in Peking gave right to the Urga ambans to decide the administrative affairs of Tusheet Khan and Setsen Khan territories. With this, Urga became the highest civil authority in the country. Based on Urga's Mongol governor Sanzaidorj's petition, the Qianlong Emperor officially recognized an annual ceremony on Bogd Khan Mountain in 1778 and provided the annual imperial donations. The city was the seat of the Jebtsundamba Khutugtus, two Qing ambans, and a Chinese trade town grew "four trees" 4.24 km (2.63 mi) east of the city center at the confluence of the Uliastai and Tuul rivers.[citation needed]

By 1778, Urga may have had as many as ten thousand monks, who were regulated by a monastic rule, Internal Rule of the Grand Monastery or Yeke Kuriyen-u Doto'adu Durem. For example, in 1797 a decree of the 4th Jebtsundamba forbade "singing, playing with archery, myagman, chess, usury and smoking"). Executions were forbidden where the holy temples of the Bogd Jebtsundama could be seen, so capital punishment took place away from the city.[citation needed]

In 1839, the 5th Bogd Jebtsundamba moved his residence to Gandan Hill, an elevated position to the west of the Baruun Damnuurchin markets. Part of the city was moved to nearby Tolgoit. In 1855, the part of the camp that moved to Tolgoit was brought back to its 1778 location, and the 7th Bogd Jebtsundamba returned to the Zuun Khuree. The Gandan Monastery flourished as a center of philosophical studies.[citation needed]

Urga and the Kyakhta trade

Following the Treaty of Kyakhta in 1727, Urga (Ulaanbaatar) was a major point of the Kyakhta trade between Russia and China – mostly Siberian furs for Chinese cloth and later tea. The route ran south to Urga, southeast across the Gobi Desert to Kalgan, and southeast over the mountains to Peking. Urga was also a collection point for goods coming from further west. These were either sent to China or shipped north to Russia via Kyakhta, because of legal restrictions and the lack of good trade routes to the west.[citation needed]

By 1908,[15] there was a Russian quarter with a few hundred merchants and a Russian club and informal Russian mayor. East of the main town was the Russian consulate, built in 1863, with an Orthodox church, a post office and 20 Cossack guards. It was fortified in 1900 and briefly occupied by troops during the Boxer Rebellion. There was a telegraph line north to Kyakhta and southeast to Kalgan and weekly postal service along these routes.[citation needed]

Beyond the Russian consulate was the Chinese trading post called Maimaicheng, and nearby the palace of the Manchu viceroy. With the growth of Western trade at the Chinese ports, the tea trade to Russia declined, some Chinese merchants left, and wool became the main export. Manufactured goods still came from Russia, but most were now brought from Kalgan by caravan. The annual trade was estimated at 25 million rubles, nine-tenths in Chinese hands and one-tenth in Russian.[citation needed]

The Moscow trade expedition of the 1910s estimated the population of Urga at 60,000, based on Nikolay Przhevalsky's study in the 1870s.[16]

The city's population swelled during the Naadam festival and major religious festivals to more than 100,000. In 1919, the number of monks had reached 20,000, up from 13,000 in 1810.[16]

Independence and Niislel Khüree

In 1910, the amban Sando went to quell a major fight between Gandan lamas and Chinese traders started by an incident at the Da Yi Yu shop in the Baruun Damnuurchin market district. He was unable to bring the lamas under control, and was forced to flee back to his quarters. In 1911, with the Qing dynasty in China headed for total collapse, Mongolian leaders in Ikh Khüree for Naadam met in secret on Mount Bogd Khan Uul and resolved to end 220 years of Manchu control of their country.[citation needed]

On 29 December 1911, the 8th Jebtsundamba Khutughtu was declared ruler of an independent Mongolia and assumed the title Bogd Khan.[11] Khüree as the seat of the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu was the logical choice for the capital of the new state. However, following the tripartite Kyakhta agreement of 1915, Mongolia's status was effectively reduced to mere autonomy.

In 1919, Mongolian nobles, over the opposition of the Bogd Khan, agreed with the Chinese resident Chen Yi on a settlement of the "Mongolian question" along Qing-era lines, but before this settlement could be put into effect, Khüree was occupied by the troops of Chinese warlord Xu Shuzheng, who forced the Mongolian nobles and clergy to renounce autonomy completely.[citation needed]

The city changed hands twice in 1921. First, on 4 February, a mixed Russian/Mongolian force led by White Russian warlord Roman von Ungern-Sternberg captured the city, freeing the Bogd Khan from Chinese imprisonment and killing a part of the Chinese garrison. Baron Ungern's capture of Urga was followed by the clearing out of Mongolia's small gangs of demoralized Chinese soldiers and, at the same time, looting and murder of foreigners, including a vicious pogrom that killed off the Jewish community.[17][18][19]

On 22 February 1921, the Bogd Khan was once again elevated to Great Khan of Mongolia in Urga.[20] However, at the same time that Baron Ungern was taking control of Urga, a Soviet-supported Communist Mongolian force led by Damdin Sükhbaatar was forming in Russia, and in March they crossed the border. Ungern and his men rode out in May to meet Red Russian and Red Mongolian troops, but suffered a disastrous defeat in June.[21]

In July 1921, the Communist Soviet-Mongolian army became the second conquering force in six months to enter Urga, and Mongolia came under the control of Soviet Russia. On 29 October 1924, the town was renamed Ulaanbaatar. On the session of the 1st Great People's Khuraldaan of Mongolia in 1924, a majority of delegates had expressed their wish to change the capital city's name to Baatar Khot (lit. 'Hero City'). However, under pressure from Turar Ryskulov, a Kazakh Soviet activist of the Communist International, the city was named Ulaanbaatar Khot (lit. 'Red-Hero City').[22]

Socialist era

During the socialist period, especially following the Second World War, most of the old ger districts were replaced by Soviet-style blocks of flats, often financed by the Soviet Union. Urban planning began in the 1950s, and most of the city today is a result of construction between 1960 and 1985.[23]

The Trans-Mongolian Railway, connecting Ulaanbaatar with Moscow and Beijing, was completed in 1956, and cinemas, theaters, museums and other modern facilities were erected. Most of the temples and monasteries of pre-socialist Khüree were destroyed following the anti-religious purges of the late 1930s. The Gandan monastery was reopened in 1944 when the U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace asked to see a monastery during his visit to Mongolia.[citation needed]

Contemporary era

Ulaanbaatar and chiefly Sükhbaatar Square was a major site of demonstrations that led to Mongolia's transition to democracy and market economy in 1990. Starting on 10 December 1989, protesters outside the Youth Culture Center called for Mongolia to implement perestroika and glasnost in their full sense. After months of large-scale demonstrations and hunger strikes, the governing Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party (MPRP) resigned on 9 March 1990. The provisional government announced Mongolia's first free elections, which were held in July. The MPRP won the election and resumed power.

Since Mongolia's transition to a market economy in 1990, the city has experienced further growth—especially in the ger districts, as construction of new blocks of flats had basically slowed to a halt in the 1990s. The population has more than doubled to over one million inhabitants. The rapid growth has caused a number of social, environmental and transportation problems. In recent years, construction of new buildings has gained new momentum, especially in the city center, and apartment prices have skyrocketed.[citation needed]

In 2008, Ulaanbaatar was the scene of riots after the Mongolian Democratic, Civic Will Party and Republican parties disputed the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party's victory in the parliamentary elections. A four-day state of emergency was declared, the capital was placed under a 22:00-to-08:00 curfew, and alcohol sales banned;[24] following these measures, rioting did not resume.[25] This was the first deadly riot in modern Ulaanbaatar's history.

In April 2013, Ulaanbaatar hosted the 7th Ministerial Conference of the Community of Democracies, and has also lent its name to the Ulaanbaatar Dialogue on Northeast Asian Security.

Demolition of historic buildings

Since 2013, a number of landmark buildings and structures have been demolished in Ulaanbaatar, despite considerable public outcry. This includes the White Gate at Nisekh in September 2013,[26] the Victims of Political Persecution Memorial Museum in October 2019,[27] the National History Museum in December 2019,[28] Buildings #3 and #6 of the National University of Mongolia,[29] and the main building of the University of Finance and Economics in 2023.[30]

The 2019 Mongolian government budget originally included items for the demolition of a number of historic neoclassical buildings in the heart of Ulaanbaatar, including the Natural History Museum, Opera and Ballet House, Drama Theatre and National Library.[31] The decision was met by a public outcry and criticism from the Union of Mongolian Architects, which demanded that the buildings be preserved and restored.[32] In January 2020, culture minister Yondonperenlein Baatarbileg denied that the government intended to demolish buildings other than the Natural History Museum, and stated that the government planned to renovate them instead.[33]

Geography

Ulaanbaatar is located at about 1,350 metres (4,430 ft) above mean sea level, slightly east of the center of Mongolia, on the Tuul River, a sub-tributary of the Selenge, in a valley at the foot of the mountain Bogd Khan Uul. Bogd Khan Uul is a broad, heavily forested mountain rising 2,250 metres (7,380 ft) to the south of Ulaanbaatar. It forms the boundary between the steppe zone to the south and the forest-steppe zone to the north. Traditionally, Ulaanbaatar is said to be surrounded by four peaks, clockwise from west: Songino Khairkhan, Chingeltei, Bayanzurkh, and finally Bogd Khan Uul.

The forests of the mountains surrounding Ulaanbaatar are composed of evergreen pines, deciduous larches and birches, while the riverine forest of the Tuul River is composed of broad-leaved, deciduous poplars, elms and willows. Ulaanbaatar lies at roughly the same latitude as Vienna, Munich, Orléans and Seattle. It lies at roughly the same longitude as Chongqing, Hanoi and Jakarta.[citation needed]

Climate

Owing to its high elevation, its relatively high latitude, its location hundreds of kilometres from any coast, and the effects of the Siberian anticyclone, Ulaanbaatar is the coldest national capital in the world,[34] with a monsoon-influenced, cold semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk, USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 3b[35]). Aside from precipitation and from a thermal standpoint, the city is on the boundary between humid continental (Dwb) and subarctic (Dwc). This is due to its 10 °C (50 °F) mean temperature for the month of May.

The city features brief, warm summers and long, bitterly cold and dry winters. The coldest January temperatures, usually at the time just before sunrise, are between −36 and −40 °C (−32.8 and −40.0 °F) with no wind, because of temperature inversion. Most of the annual precipitation of 267 millimetres (10.51 in) falls from May to September. The highest recorded annual precipitation in the city was 659 millimetres or 25.94 inches at the Khureltogoot Astronomical Observatory on Mount Bogd Khan Uul. Ulaanbaatar has an average annual temperature of 0.2 °C or 32.4 °F,[36] making it the coldest capital in the world (almost as cold as Nuuk, Greenland, but Greenland is not independent). Nuuk has a tundra climate with consistent cold temperatures throughout the year. Ulaanbaatar's annual average is brought down by its cold winter temperatures even though it is significantly warm from late April to early October.

The city lies in the zone of discontinuous permafrost, which means that building is difficult in sheltered locations that preclude thawing in the summer, but easier on more exposed ones where soils fully thaw. Suburban residents live in traditional yurts that do not protrude into the soil.[37] Extreme temperatures in the city range from −43.9 °C (−47.0 °F) in January 1957 to 39.0 °C (102.2 °F) in July 1988.[38]

| Climate data for Ulaanbaatar (1991-2020, extremes 1869-present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

28.7 (83.7) |

33.5 (92.3) |

38.3 (100.9) |

39.0 (102.2) |

36.7 (98.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

39.0 (102.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −15.5 (4.1) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

23.1 (73.6) |

25.2 (77.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

17.2 (63.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−13.7 (7.3) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −21.3 (−6.3) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

3.0 (37.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−19.0 (−2.2) |

0.2 (32.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −25.6 (−14.1) |

−21.7 (−7.1) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

11.1 (52.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−15.1 (4.8) |

−22.9 (−9.2) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −43.9 (−47.0) |

−42.2 (−44.0) Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Ulanbaatar Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk | |||||||||||