A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

French Republic République française (French) | |

|---|---|

| 1870–1940 | |

| Motto: Liberté, égalité, fraternité ("Liberty, equality, fraternity") | |

| Anthem: La Marseillaise ("The Marseillaise") | |

Great Seal of France:  | |

The French Republic in 1939

| |

Territories and colonies of the French Republic in 1939

| |

| Capital and largest city | Paris 48°52′13″N 02°18′59″E / 48.87028°N 2.31639°E |

| Common languages | French (official), several others |

| Religion | |

| Demonym(s) | French |

| Government |

|

| President | |

• 1871–1873 (first) | Adolphe Thiers |

• 1932–1940 (last) | Albert Lebrun |

| Prime Minister | |

• 1870–1871 (first) | Louis Jules Trochu |

• 1940 (last) | Philippe Pétain |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| History | |

• Proclamation by Leon Gambetta | 4 September 1870 |

| 15 November 1885 | |

• France enters the Great War | 3 August 1914 |

| 28 June 1919 | |

• France enters World War II | 3 September 1939 |

| 10 May – 25 June 1940 | |

• Vichy France declared | 10 July 1940 |

| Area | |

| 1894 (Metropolitan France) | 536,464 km2 (207,130 sq mi) |

| 1938 (including colonies) | 13,500,000[1][2] km2 (5,200,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1938 (including colonies) | 150,000,000[3] |

| Currency | French Franc |

| ISO 3166 code | FR |

| Today part of | |

The French Third Republic (French: Troisième République, sometimes written as La IIIe République) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France during World War II led to the formation of the Vichy government.

The early days of the Third Republic were dominated by political disruption caused by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, which the Republic continued to wage after the fall of Emperor Napoleon III in 1870. Social upheaval and the Paris Commune preceded the final defeat. The German Empire, proclaimed by the German invaders in Palace of Versailles, annexed the French regions of Alsace (keeping the Territoire de Belfort) and Lorraine (the northeastern part, i.e. present-day department of Moselle). The early governments of the Third Republic considered re-establishing the monarchy, but disagreement as to the nature of that monarchy and the rightful occupant of the throne could not be resolved. Consequently, the Third Republic, originally envisioned as a provisional government, instead became the permanent form of government of France.

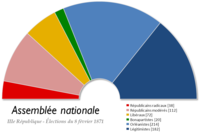

The French Constitutional Laws of 1875 defined the composition of the Third Republic. It consisted of a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate to form the legislative branch of government and a president to serve as head of state. Calls for the re-establishment of the monarchy dominated the tenures of the first two presidents, Adolphe Thiers and Patrice de MacMahon, but growing support for the republican form of government among the French populace and a series of republican presidents in the 1880s gradually quashed prospects of a monarchical restoration.

The Third Republic established many French colonial possessions, including French Indochina, French Madagascar, French Polynesia, and large territories in West Africa during the Scramble for Africa, all of them acquired during the last two decades of the 19th century. The early years of the 20th century were dominated by the Democratic Republican Alliance, which was originally conceived as a centre-left political alliance, but over time became the main centre-right party. The period from the start of World War I to the late 1930s featured sharply polarized politics, between the Democratic Republican Alliance and the Radicals. The government fell less than a year after the outbreak of World War II, when Nazi forces occupied much of France, and was replaced by the rival governments of Charles de Gaulle's Free France (La France libre) and Philippe Pétain's French State (L'État français).

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the French colonial empire was the second largest colonial empire in the world only behind the British Empire; it extended over 13,500,000 km2 (5,200,000 sq mi) of land at its height in the 1920s and 1930s. In terms of population however, on the eve of World War II, France and its colonial possessions totaled only 150 million inhabitants, compared with 330 million for British India alone.

Adolphe Thiers called republicanism in the 1870s "the form of government that divides France least"; however, politics under the Third Republic were sharply polarized. On the left stood reformist France, heir to the French Revolution. On the right stood conservative France, rooted in the peasantry, the Catholic Church, and the army.[4] In spite of France's sharply divided electorate and persistent attempts to overthrow it, the Third Republic endured for 70 years, which makes it the longest-lasting system of government in France since the collapse of the Ancien Régime in 1789.[5]

Origins and formation

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 resulted in the defeat of France and the overthrow of Emperor Napoleon III and his Second French Empire. After Napoleon's capture by the Prussians at the Battle of Sedan (1 September 1870), Parisian deputies led by Léon Gambetta established the Government of National Defence as a provisional government on 4 September 1870. The deputies then selected General Louis-Jules Trochu to serve as its president. This first government of the Third Republic ruled during the Siege of Paris (19 September 1870 – 28 January 1871). As Paris was cut off from the rest of unoccupied France, the Minister of War Léon Gambetta succeeded in leaving Paris in a hot air balloon, and established the provisional republican government in the city of Tours on the Loire river.

After the French surrender in January 1871, the provisional Government of National Defence disbanded, and national elections were called to elect a new French government. French territories occupied by Prussia at the time did not participate. The resulting conservative National Assembly elected Adolphe Thiers head of a provisional government, ("head of the executive branch of the Republic pending a decision on the institutions of France". The new government negotiated a peace settlement with the newly proclaimed German Empire: the Treaty of Frankfurt signed on 10 May 1871. To prompt the Prussians to leave France, the government passed a variety of financial laws, such as the controversial Law of Maturities, to pay reparations.

In Paris, resentment built against the government from late March through May 1871. Paris workers and National Guards revolted and took power as the Paris Commune. which maintained a radical left-wing regime for two months until the Thiers government bloodily suppressed it in May 1871. The ensuing repression of the communards had disastrous consequences for the labour movement.

Attempts to restore the monarchy

The French legislative election of 1871, held in the aftermath when the regime of Napoleon III collapsed, resulted in a monarchist majority in the French National Assembly that favoured a peace agreement with Prussia. Planning to restore the monarchy, the "Legitimists" in the National Assembly supported the candidacy of Henri, Comte de Chambord, alias "Henry V," grandson of King Charles X, the last king from the senior line of the Bourbon Dynasty. The Orléanists supported Louis-Philippe, Comte de Paris a grandson of King Louis Philippe I, who replaced his cousin Charles X in 1830. The Bonapartists lost legitimacy due to the defeat of Napoléon III and were unable to advance the candidacy of any member of the Bonaparte family.

Legitimists and Orléanists eventually agreed on the childless Comte de Chambord as king, with the Comte de Paris as his heir. This was the expected line of succession for the Comte de Chambord based on France's traditional rule of agnatic primogeniture if the renunciation of the Spanish Bourbons in the Peace of Utrecht was recognised. Consequently, in 1871 the throne was offered to the Comte de Chambord.[6]

Monarchists' republic and constitutional crisis

Chambord believed the restored monarchy had to eliminate all traces of the Revolution (most famously including the tricolore), to restore unity between the monarchy and the nation. Compromise on this was impossible, Chambord believed, if the nation were to be made whole again. The general population, however, was unwilling to abandon the Tricolour flag. Monarchists therefore resigned themselves to delay the monarchy until the death of the ageing, childless Chambord, then to offer the throne to his more liberal heir, the Comte de Paris. A "temporary" republican government was therefore established. Chambord lived on until 1883, but by that time, enthusiasm for a monarchy had faded, and the Comte de Paris was never offered the French throne.[7]

Following the French surrender to Prussia in January 1871, concluding the Franco-Prussian War, the transitional Government of National Defence established a new seat of government at Versailles due to the encirclement of Paris by Prussian forces. New representatives were elected in February of that year, constituting the government which would come to evolve into the Third Republic. These representatives – predominantly conservative republicans – enacted a series of legislation which prompted resistance and outcry from radical and leftist elements of the republican movement. In Paris, a series of public altercations broke out between the Versailles-aligned Parisian government and the city's radical socialists. The radicals ultimately rejected the authority of Versailles, responding with the foundation of the Paris Commune in March.

The principles underpinning the Commune were viewed as morally degenerate by French conservatives at large while the government at Versailles sought to maintain the tenuous post-war stability which it had established. In May, the regular French Armed Forces, under the command of Patrice de MacMahon and the Versailles government, marched on Paris and succeeded in dismantling the Commune during what would become known as The Bloody Week. The term ordre moral ("moral order") subsequently came to be applied to the budding Third Republic due to the perceived restoration of conservative policies and values following the suppression of the Commune.[8]

De MacMahon, his popularity bolstered by his victory over the Commune, was later elected President of the Republic in May 1873 and would hold the office until January 1879. A staunch Catholic conservative with Legitimist sympathies and a noted mistrust of secularists, de MacMahon grew to be increasingly at odds with the French parliament as liberal and secular republicans gained a legislative majority during his presidency.

In February 1875, a series of parliamentary acts established the constitutional laws of the new republic. At its head was a President of the Republic. A two-chamber parliament consisting of a directly-elected Chamber of Deputies and an indirectly-elected Senate was created, along with a ministry under the President of the Council (prime minister), who was nominally answerable to both the President of the Republic and the legislature. Throughout the 1870s, the issue of whether a monarchy should replace or oversee the republic dominated public debate.

The elections of 1876 demonstrated strong public support for the increasingly anti-monarchist republican movement. A decisive Republican majority was elected to the Chamber of Deputies while the monarchist majority in the Senate was maintained by only one seat. President de MacMahon responded in May 1877, attempting to quell the Republicans' rising popularity and limit their political influence through a series of actions known as le seize Mai.

On 16 May 1877, de MacMahon forced the resignation of Moderate Republican prime minister Jules Simon and appointed the Orléanist Albert de Broglie to the office. The Chamber of Deputies declared the appointment illegitimate, exceeding the president's powers, and refused to cooperate with either de MacMahon or de Broglie. De MacMahon then dissolved the Chamber and called for a new general election to be held the following October. He was subsequently accused by Republicans and their sympathizers of attempting a constitutional coup d'état, which he denied.

The October elections again brought a Republican majority to the Chamber of Deputies, reiterating public opinion. The Republicans would go on to gain a majority in the Senate by January 1879, establishing dominance in both houses and effectively ending the potential for a monarchist restoration. De MacMahon himself resigned on 30 January 1879 to be succeeded by the moderate Republican Jules Grévy.[9] He promised that he would not use his presidential power of dissolution, and therefore lost his control over the legislature, effectively creating a parliamentary system that would be maintained until the end of the Third Republic.[10]

Republicans take power

Following the 16 May crisis in 1877, Legitimists were pushed out of power, and the Republic was finally governed by Moderate Republicans (pejoratively labelled "Opportunist Republicans" by Radical Republicans) who supported moderate social and political changes to nurture the new regime. The Jules Ferry laws making public education free, mandatory, and secular (laїque), were voted in 1881 and 1882, one of the first signs of the expanding civic powers of the Republic. From that time onward, the Catholic clergy lost control of public education.[11]

To discourage the monarchists, the French Crown Jewels were broken up and sold in 1885. Only a few crowns were kept, their precious gems replaced by coloured glass.

Politics during the Belle Époque

Boulanger crisis

In 1889, the Republic was rocked by a sudden political crisis precipitated by General Georges Boulanger. An enormously popular general, he won a series of elections in which he would resign his seat in the Chamber of Deputies and run again in another district. At the apogee of his popularity in January 1889, he posed the threat of a coup d'état and the establishment of a dictatorship. With his base of support in the working districts of Paris and other cities, plus rural traditionalist Catholics and royalists, he promoted an aggressive nationalism aimed against Germany. The elections of September 1889 marked a decisive defeat for the Boulangists. They were defeated by the changes in the electoral laws that prevented Boulanger from running in multiple constituencies; by the government's aggressive opposition; and by the absence of the general himself, in self-imposed exile with his mistress. The fall of Boulanger severely undermined the conservative and royalist elements within France; they would not recover until 1940.[12]

Revisionist scholars have argued that the Boulangist movement more often represented elements of the radical left rather than the extreme right. Their work is part of an emerging consensus that France's radical right was formed in part during the Dreyfus era by men who had been Boulangist partisans of the radical left a decade earlier.[13]

Panama scandal

The Panama scandals of 1892, regarded as the largest financial fraud of the 19th century, involved a failed attempt to build the Panama Canal. Plagued by disease, death, inefficiency, and widespread corruption, and its troubles covered up by bribed French officials, the Panama Canal Company went bankrupt. Its stock became worthless, and ordinary investors lost close to a billion francs.[14]

Welfare state and public health

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Timeline |

|

|

France lagged behind Bismarckian Germany, as well as Great Britain and Ireland, in developing a welfare state with public health, unemployment insurance and national old age pension plans. There was an accident insurance law for workers in 1898, and in 1910, France created a national pension plan. Unlike Germany or Britain, the programs were much smaller – for example, pensions were a voluntary plan.[15] Historian Timothy Smith finds French fears of national public assistance programs were grounded in a widespread disdain for the English Poor Law.[16] Tuberculosis was the most dreaded disease of the day, especially striking young people in their twenties. Germany set up vigorous measures of public hygiene and public sanatoria, but France let private physicians handle the problem.[17] The French medical profession guarded its prerogatives, and public health activists were not as well organized or as influential as in Germany, Britain or the United States.[18][19] For example, there was a long battle over a public health law which began in the 1880s as a campaign to reorganize the nation's health services, to require the registration of infectious diseases, to mandate quarantines, and to improve the deficient health and housing legislation of 1850.

However, the reformers met opposition from bureaucrats, politicians, and physicians. Because it was so threatening to so many interests, the proposal was debated and postponed for 20 years before becoming law in 1902. Implementation finally came when the government realized that contagious diseases had a national security impact in weakening military recruits, and keeping the population growth rate well below Germany's.[20] There is no evidence to suggest than French life expectancy was lower than that of Germany.[21][22]

Radicals' republic

The most important party of the early 20th century in France was the Radical Party, founded in 1901 as the "Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party" ("Parti républicain, radical et radical-socialiste"). It was classically liberal in political orientation and opposed the monarchists and clerical elements on the one hand, and the Socialists on the other. Many members had been recruited by the Freemasons.[23] The Radicals were split between activists who called for state intervention to achieve economic and social equality and conservatives whose first priority was stability. The workers' demands for strikes threatened such stability and pushed many Radicals toward conservatism. It opposed women's suffrage for fear that women would vote for its opponents or for candidates endorsed by the Catholic Church.[24] It favoured a progressive income tax, economic equality, expanded educational opportunities and cooperatives in domestic policy. In foreign policy, it favoured a strong League of Nations after the war, and the maintenance of peace through compulsory arbitration, controlled disarmament, economic sanctions, and perhaps an international military force.[25]

Followers of Léon Gambetta, such as Raymond Poincaré, who would become President of the Council in the 1920s, created the Democratic Republican Alliance (ARD), which became the main center-right party after World War I.[26]

Governing coalitions collapsed with regularity, rarely lasting more than a few months, as radicals, socialists, liberals, conservatives, republicans and monarchists all fought for control. Some historians argue that the collapses were not important because they reflected minor changes in coalitions of many parties that routinely lost and gained a few allies. Consequently, the change of governments could be seen as little more than a series of ministerial reshuffles, with many individuals carrying forward from one government to the next, often in the same posts.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Third_French_RepublicText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk