A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalized belief about a particular category of people.[2] It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can be, for example, an expectation about the group's personality, preferences, appearance or ability. Stereotypes are often overgeneralized, inaccurate, and resistant to new information.[3] A stereotype does not necessarily need to be a negative assumption. They may be positive, neutral, or negative.

Explicit stereotypes

An explicit stereotype refers to stereotypes that one is aware that one holds, and is aware that one is using to judge people. If person A is making judgments about a particular person B from group G, and person A has an explicit stereotype for group G, their decision bias can be partially mitigated using conscious control; however, attempts to offset bias due to conscious awareness of a stereotype often fail at being truly impartial, due to either underestimating or overestimating the amount of bias being created by the stereotype.

Implicit stereotypes

Implicit stereotypes are those that lay on individuals' subconsciousness, that they have no control or awareness of.[4] "Implicit stereotypes are built based on two concepts, associative networks in semantic (knowledge) memory and automatic activation".[5] Implicit stereotypes are automatic and involuntary associations that people make between a social group and a domain or attribute. For example, one can have beliefs that women and men are equally capable of becoming successful electricians but at the same time many can associate electricians more with men than women.[5]

In social psychology, a stereotype is any thought widely adopted about specific types of individuals or certain ways of behaving intended to represent the entire group of those individuals or behaviors as a whole.[6] These thoughts or beliefs may or may not accurately reflect reality.[7][8] Within psychology and across other disciplines, different conceptualizations and theories of stereotyping exist, at times sharing commonalities, as well as containing contradictory elements. Even in the social sciences and some sub-disciplines of psychology, stereotypes are occasionally reproduced and can be identified in certain theories, for example, in assumptions about other cultures.[9]

Etymology

The term stereotype comes from the French adjective stéréotype and derives from the Greek words στερεός (stereos), 'firm, solid'[10] and τύπος (typos), 'impression',[11] hence 'solid impression on one or more ideas/theories'.

The term was first used in the printing trade in 1798 by Firmin Didot, to describe a printing plate that duplicated any typography. The duplicate printing plate, or the stereotype, is used for printing instead of the original.

Outside of printing, the first reference to stereotype in English was in 1850, as a noun that meant 'image perpetuated without change'.[12] However, it was not until 1922 that stereotype was first used in the modern psychological sense by American journalist Walter Lippmann in his work Public Opinion.[13]

Relationship with other types of intergroup attitudes

Stereotypes, prejudice, racism, and discrimination[14] are understood as related but different concepts.[15][16][17][18] Stereotypes are regarded as the most cognitive component and often occurs without conscious awareness, whereas prejudice is the affective component of stereotyping and discrimination is one of the behavioral components of prejudicial reactions.[15][16][19] In this tripartite view of intergroup attitudes, stereotypes reflect expectations and beliefs about the members of groups perceived as different from one's own, prejudice represents the emotional response, and discrimination refers to actions.[15][16]

Although related, the three concepts can exist independently of each other.[16][20] According to Daniel Katz and Kenneth Braly, stereotyping leads to racial prejudice when people emotionally react to the name of a group, ascribe characteristics to members of that group, and then evaluate those characteristics.[17]

Possible prejudicial effects of stereotypes[8] are:

- Justification of ill-founded prejudices or ignorance

- Unwillingness to rethink one's attitudes and behavior

- Preventing some people of stereotyped groups from entering or succeeding in activities or fields[21]

Content

Stereotype content refers to the attributes that people think characterize a group. Studies of stereotype content examine what people think of others, rather than the reasons and mechanisms involved in stereotyping.[22]

Early theories of stereotype content proposed by social psychologists such as Gordon Allport assumed that stereotypes of outgroups reflected uniform antipathy.[23][24] For instance, Katz and Braly argued in their classic 1933 study that ethnic stereotypes were uniformly negative.[22]

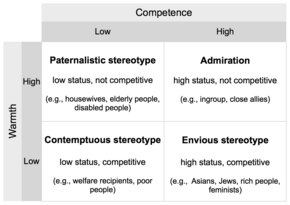

By contrast, a newer model of stereotype content theorizes that stereotypes are frequently ambivalent and vary along two dimensions: warmth and competence. Warmth and competence are respectively predicted by lack of competition and status. Groups that do not compete with the in-group for the same resources (e.g., college space) are perceived as warm, whereas high-status (e.g., economically or educationally successful) groups are considered competent. The groups within each of the four combinations of high and low levels of warmth and competence elicit distinct emotions.[25] The model explains the phenomenon that some out-groups are admired but disliked, whereas others are liked but disrespected. This model was empirically tested on a variety of national and international samples and was found to reliably predict stereotype content.[23][26]

An even more recent model of stereotype content called the agency–beliefs–communion (ABC) model suggested that methods to study warmth and competence in the stereotype content model (SCM) were missing a crucial element, that being, stereotypes of social groups are often spontaneously generated.[27] Experiments on the SCM usually ask participants to rate traits according to warmth and competence but this does not allow participants to use any other stereotype dimensions.[28] The ABC model, proposed by Koch and colleagues in 2016 is an estimate of how people spontaneously stereotype U.S social groups of people using traits. Koch et al. conducted several studies asking participants to list groups and sort them according to their similarity.[27] Using statistical techniques, they revealed three dimensions that explained the similarity ratings. These three dimensions were agency (A), beliefs (B), and communion (C). Agency is associated with reaching goals, standing out and socio-economic status and is related to competence in the SCM, with some examples of traits including poor and wealthy, powerful and powerless, low status and high status. Beliefs is associated with views on the world, morals and conservative-progressive beliefs with some examples of traits including traditional and modern, religious and science-oriented or conventional and alternative. Finally, communion is associated with connecting with others and fitting in and is similar to warmth from the SCM, with some examples of traits including trustworthy and untrustworthy, cold and warm and repellent and likeable.[29] According to research using this model, there is a curvilinear relationship between agency and communion.[30] For example, if a group is high or low in the agency dimension then they may be seen as un-communal, whereas groups that are average in agency are seen as more communal.[31] This model has many implications in predicting behaviour towards stereotyped groups. For example, Koch and colleagues recently proposed that perceived similarity in agency and beliefs increases inter-group cooperation.[32]

Functions

Early studies suggested that stereotypes were only used by rigid, repressed, and authoritarian people. This idea has been refuted by contemporary studies that suggest the ubiquity of stereotypes and it was suggested to regard stereotypes as collective group beliefs, meaning that people who belong to the same social group share the same set of stereotypes.[20] Modern research asserts that full understanding of stereotypes requires considering them from two complementary perspectives: as shared within a particular culture/subculture and as formed in the mind of an individual person.[33]

Relationship between cognitive and social functions

Stereotyping can serve cognitive functions on an interpersonal level, and social functions on an intergroup level.[8][20] For stereotyping to function on an intergroup level (see social identity approaches: social identity theory and self-categorization theory), an individual must see themselves as part of a group and being part of that group must also be salient for the individual.[20]

Craig McGarty, Russell Spears, and Vincent Y. Yzerbyt (2002) argued that the cognitive functions of stereotyping are best understood in relation to its social functions, and vice versa.[34]

Cognitive functions

Stereotypes can help make sense of the world. They are a form of categorization that helps to simplify and systematize information. Thus, information is more easily identified, recalled, predicted, and reacted to.[20] Stereotypes are categories of objects or people. Between stereotypes, objects or people are as different from each other as possible.[6] Within stereotypes, objects or people are as similar to each other as possible.[6]

Gordon Allport has suggested possible answers to why people find it easier to understand categorized information.[35] First, people can consult a category to identify response patterns. Second, categorized information is more specific than non-categorized information, as categorization accentuates properties that are shared by all members of a group. Third, people can readily describe objects in a category because objects in the same category have distinct characteristics. Finally, people can take for granted the characteristics of a particular category because the category itself may be an arbitrary grouping.

A complementary perspective theorizes how stereotypes function as time- and energy-savers that allow people to act more efficiently.[6] Yet another perspective suggests that stereotypes are people's biased perceptions of their social contexts.[6] In this view, people use stereotypes as shortcuts to make sense of their social contexts, and this makes a person's task of understanding his or her world less cognitively demanding.[6]

Social functions

Social categorization

In the following situations, the overarching purpose of stereotyping is for people to put their collective self (their in-group membership) in a positive light:[36]

- when stereotypes are used for explaining social events

- when stereotypes are used for justifying activities of one's own group (ingroup) to another group (outgroup)

- when stereotypes are used for differentiating the ingroup as positively distinct from outgroups

Explanation purposes

As mentioned previously, stereotypes can be used to explain social events.[20][36] Henri Tajfel[20] described his observations of how some people found that the antisemitic fabricated contents of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion only made sense if Jews have certain characteristics. Therefore, according to Tajfel,[20] Jews were stereotyped as being evil and yearning for world domination to match the antisemitic "facts" as presented in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Justification purposes

People create stereotypes of an outgroup to justify the actions that their in-group has committed (or plans to commit) towards that outgroup.[20][35][36] For example, according to Tajfel,[20] Europeans stereotyped African, Indian, and Chinese people as being incapable of achieving financial advances without European help. This stereotype was used to justify European colonialism in Africa, India, and China.

Intergroup differentiation

An assumption is that people want their ingroup to have a positive image relative to outgroups, and so people want to differentiate their ingroup from relevant outgroups in a desirable way.[20] If an outgroup does not affect the ingroup's image, then from an image preservation point of view, there is no point for the ingroup to be positively distinct from that outgroup.[20]

People can actively create certain images for relevant outgroups by stereotyping. People do so when they see that their ingroup is no longer as clearly and/or as positively differentiated from relevant outgroups, and they want to restore the intergroup differentiation to a state that favours the ingroup.[20][36]

Self-categorization

Stereotypes can emphasize a person's group membership in two steps: Stereotypes emphasize the person's similarities with ingroup members on relevant dimensions, and also the person's differences from outgroup members on relevant dimensions.[24] People change the stereotype of their ingroups and outgroups to suit context.[24] Once an outgroup treats an ingroup member badly, they are more drawn to the members of their own group.[37] This can be seen as members within a group are able to relate to each other though a stereotype because of identical situations. A person can embrace a stereotype to avoid humiliation such as failing a task and blaming it on a stereotype.[38]

Social influence and consensus

Stereotypes are an indicator of ingroup consensus.[36] When there are intragroup disagreements over stereotypes of the ingroup and/or outgroups, ingroup members take collective action to prevent other ingroup members from diverging from each other.[36]

John C. Turner proposed in 1987[36] that if ingroup members disagree on an outgroup stereotype, then one of three possible collective actions follow: First, ingroup members may negotiate with each other and conclude that they have different outgroup stereotypes because they are stereotyping different subgroups of an outgroup (e.g., Russian gymnasts versus Russian boxers). Second, ingroup members may negotiate with each other, but conclude that they are disagreeing because of categorical differences amongst themselves. Accordingly, in this context, it is better to categorise ingroup members under different categories (e.g., Democrats versus Republican) than under a shared category (e.g., American). Finally, ingroup members may influence each other to arrive at a common outgroup stereotype.

Formation

Different disciplines give different accounts of how stereotypes develop: Psychologists may focus on an individual's experience with groups, patterns of communication about those groups, and intergroup conflict. As for sociologists, they may focus on the relations among different groups in a social structure. They suggest that stereotypes are the result of conflict, poor parenting, and inadequate mental and emotional development. Once stereotypes have formed, there are two main factors that explain their persistence. First, the cognitive effects of schematic processing (see schema) make it so that when a member of a group behaves as we expect, the behavior confirms and even strengthens existing stereotypes. Second, the affective or emotional aspects of prejudice render logical arguments against stereotypes ineffective in countering the power of emotional responses.[39]

Correspondence bias

Correspondence bias refers to the tendency to ascribe a person's behavior to disposition or personality, and to underestimate the extent to which situational factors elicited the behavior. Correspondence bias can play an important role in stereotype formation.[40]

For example, in a study by Roguer and Yzerbyt (1999) participants watched a video showing students who were randomly instructed to find arguments either for or against euthanasia. The students that argued in favor of euthanasia came from the same law department or from different departments. Results showed that participants attributed the students' responses to their attitudes although it had been made clear in the video that students had no choice about their position. Participants reported that group membership, i.e., the department that the students belonged to, affected the students' opinions about euthanasia. Law students were perceived to be more in favor of euthanasia than students from different departments despite the fact that a pretest had revealed that subjects had no preexisting expectations about attitudes toward euthanasia and the department that students belong to. The attribution error created the new stereotype that law students are more likely to support euthanasia.[41]

Nier et al. (2012) found that people who tend to draw dispositional inferences from behavior and ignore situational constraints are more likely to stereotype low-status groups as incompetent and high-status groups as competent. Participants listened to descriptions of two fictitious groups of Pacific Islanders, one of which was described as being higher in status than the other. In a second study, subjects rated actual groups – the poor and wealthy, women and men – in the United States in terms of their competence. Subjects who scored high on the measure of correspondence bias stereotyped the poor, women, and the fictitious lower-status Pacific Islanders as incompetent whereas they stereotyped the wealthy, men, and the high-status Pacific Islanders as competent. The correspondence bias was a significant predictor of stereotyping even after controlling for other measures that have been linked to beliefs about low status groups, the just-world hypothesis and social dominance orientation.[42]

Based on the anti-public sector bias,[43] Döring and Willems (2021)[44] found that employees in the public sector are considered as less professional compared to employees in the private sector. They build on the assumption that the red-tape and bureaucratic nature of the public sector spills over in the perception that citizens have about the employees working in the sector. With an experimental vignette study, they analyze how citizens process information on employees' sector affiliation, and integrate non-work role-referencing to test the stereotype confirmation assumption underlying the representativeness heuristic. The results show that sector as well as non-work role-referencing influences perceived employee professionalism but has little effect on the confirmation of particular public sector stereotypes.[45] Moreover, the results do not confirm a congruity effect of consistent stereotypical information: non-work role-referencing does not aggravate the negative effect of sector affiliation on perceived employee professionalism.

Illusory correlation

Research has shown that stereotypes can develop based on a cognitive mechanism known as illusory correlation – an erroneous inference about the relationship between two events.[6][46][47] If two statistically infrequent events co-occur, observers overestimate the frequency of co-occurrence of these events. The underlying reason is that rare, infrequent events are distinctive and salient and, when paired, become even more so. The heightened salience results in more attention and more effective encoding, which strengthens the belief that the events are correlated.[48][49][50]

In the inter-group context, illusory correlations lead people to misattribute rare behaviors or traits at higher rates to minority group members than to majority groups, even when both display the same proportion of the behaviors or traits. Black people, for instance, are a minority group in the United States and interaction with blacks is a relatively infrequent event for an average white American.[51] Similarly, undesirable behavior (e.g. crime) is statistically less frequent than desirable behavior. Since both events "blackness" and "undesirable behavior" are distinctive in the sense that they are infrequent, the combination of the two leads observers to overestimate the rate of co-occurrence.[48] Similarly, in workplaces where women are underrepresented and negative behaviors such as errors occur less frequently than positive behaviors, women become more strongly associated with mistakes than men.[52]

In a landmark study, David Hamilton and Richard Gifford (1976) examined the role of illusory correlation in stereotype formation. Subjects were instructed to read descriptions of behaviors performed by members of groups A and B. Negative behaviors outnumbered positive actions and group B was smaller than group A, making negative behaviors and membership in group B relatively infrequent and distinctive. Participants were then asked who had performed a set of actions: a person of group A or group B. Results showed that subjects overestimated the frequency with which both distinctive events, membership in group B and negative behavior, co-occurred, and evaluated group B more negatively. This despite the fact the proportion of positive to negative behaviors was equivalent for both groups and that there was no actual correlation between group membership and behaviors.[48] Although Hamilton and Gifford found a similar effect for positive behaviors as the infrequent events, a meta-analytic review of studies showed that illusory correlation effects are stronger when the infrequent, distinctive information is negative.[46]

Hamilton and Gifford's distinctiveness-based explanation of stereotype formation was subsequently extended.[49] A 1994 study by McConnell, Sherman, and Hamilton found that people formed stereotypes based on information that was not distinctive at the time of presentation, but was considered distinctive at the time of judgement.[53] Once a person judges non-distinctive information in memory to be distinctive, that information is re-encoded and re-represented as if it had been distinctive when it was first processed.[53]

Common environment

One explanation for why stereotypes are shared is that they are the result of a common environment that stimulates people to react in the same way.[6]

The problem with the 'common environment' is that explanation in general is that it does not explain how shared stereotypes can occur without direct stimuli.[6] Research since the 1930s suggested that people are highly similar with each other in how they describe different racial and national groups, although those people have no personal experience with the groups they are describing.[54]

Socialization and upbringing

Another explanation says that people are socialised to adopt the same stereotypes.[6] Some psychologists believe that although stereotypes can be absorbed at any age, stereotypes are usually acquired in early childhood under the influence of parents, teachers, peers, and the media.

If stereotypes are defined by social values, then stereotypes only change as per changes in social values.[6] The suggestion that stereotype content depends on social values reflects Walter Lippman's argument in his 1922 publication that stereotypes are rigid because they cannot be changed at will.[17]

Studies emerging since the 1940s refuted the suggestion that stereotype contents cannot be changed at will. Those studies suggested that one group's stereotype of another group would become more or less positive depending on whether their intergroup relationship had improved or degraded.[17][55][56] Intergroup events (e.g., World War II, Persian Gulf conflicts) often changed intergroup relationships. For example, after WWII, Black American students held a more negative stereotype of people from countries that were the United States's WWII enemies.[17] If there are no changes to an intergroup relationship, then relevant stereotypes do not change.[18]

Intergroup relations

According to a third explanation, shared stereotypes are neither caused by the coincidence of common stimuli, nor by socialisation. This explanation posits that stereotypes are shared because group members are motivated to behave in certain ways, and stereotypes reflect those behaviours.[6] It is important to note from this explanation that stereotypes are the consequence, not the cause, of intergroup relations. This explanation assumes that when it is important for people to acknowledge both their ingroup and outgroup, they will emphasise their difference from outgroup members, and their similarity to ingroup members.[6] International migration creates more opportunities for intergroup relations, but the interactions do not always disconfirm stereotypes. They are also known to form and maintain them.[57]

Activation

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=StereotypesText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk