A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Sexual attitudes and behaviors in ancient Rome are indicated by art, literature, and inscriptions, and to a lesser extent by archaeological remains such as erotic artifacts and architecture. It has sometimes been assumed that "unlimited sexual license" was characteristic of ancient Rome,[1][2] but sexuality was not excluded as a concern of the mos maiorum, the traditional social norms that affected public, private, and military life.[3] Pudor, "shame, modesty", was a regulating factor in behavior,[4] as were legal strictures on certain sexual transgressions in both the Republican and Imperial periods.[5] The censors—public officials who determined the social rank of individuals—had the power to remove citizens from the senatorial or equestrian order for sexual misconduct, and on occasion did so.[6][7] The mid-20th-century sexuality theorist Michel Foucault regarded sex throughout the Greco-Roman world as governed by restraint and the art of managing sexual pleasure.[8]

Roman society was patriarchal (see paterfamilias), and masculinity was premised on a capacity for governing oneself and others of lower status, not only in war and politics, but also in sexual relations.[9] Virtus, "virtue", was an active masculine ideal of self-discipline, related to the Latin word for "man", vir. The corresponding ideal for a woman was pudicitia, often translated as chastity or modesty, but it was a more positive and even competitive personal quality that displayed both her attractiveness and self-control.[10] Roman women of the upper classes were expected to be well educated, strong of character, and active in maintaining their family's standing in society.[11] With extremely few exceptions, surviving Latin literature preserves the voices of educated male Romans on sexuality. Visual art was created by those of lower social status and of a greater range of ethnicity, but was tailored to the taste and inclinations of those wealthy enough to afford it, including, in the Imperial era, former slaves.[12]

Some sexual attitudes and behaviors in ancient Roman culture differ markedly from those in later Western societies.[13][14] Roman religion promoted sexuality as an aspect of prosperity for the state, and individuals might turn to private religious practice or "magic" for improving their erotic lives or reproductive health. Prostitution was legal, public, and widespread.[15] "Pornographic" paintings were featured among the art collections in respectable upperclass households.[16] It was considered natural and unremarkable for men to be sexually attracted to teen-aged youths of both sexes, and even pederasty was condoned as long as the younger male partner was not a freeborn Roman. "Homosexual" and "heterosexual" did not form the primary dichotomy of Roman thinking about sexuality, and no Latin words for these concepts exist.[17] No moral censure was directed at the man who enjoyed sex acts with either women or males of inferior status, as long as his behaviors revealed no weaknesses or excesses, nor infringed on the rights and prerogatives of his masculine peers. While perceived effeminacy was denounced, especially in political rhetoric, sex in moderation with male prostitutes or slaves was not regarded as improper or vitiating to masculinity, if the male citizen took the active and not the receptive role. Hypersexuality, however, was condemned morally and medically in both men and women. Women were held to a stricter moral code,[18] and same-sex relations between women are poorly documented, but the sexuality of women is variously celebrated or reviled throughout Latin literature. In general the Romans had more fluid gender boundaries than the ancient Greeks.[19]

A late-20th-century paradigm analyzed Roman sexuality in relation to a "penetrator–penetrated" binary model. This model, however, has limitations, especially in regard to expressions of sexuality among individual Romans.[20] Even the relevance of the word "sexuality" to ancient Roman culture has been disputed;[21][22][23] but in the absence of any other label for "the cultural interpretation of erotic experience", the term continues to be used.[24]

Erotic literature and art

Ancient literature pertaining to Roman sexuality falls mainly into four categories: legal texts; medical texts; poetry; and political discourse.[25] Forms of expression with lower cultural cachet in antiquity—such as comedy, satire, invective, love poetry, graffiti, magic spells, inscriptions, and interior decoration—have more to say about sex than elevated genres such as epic and tragedy. Information about the sex lives of the Romans is scattered in historiography, oratory, philosophy, and writings on medicine, agriculture, and other technical topics.[26] Legal texts point to behaviors Romans wanted to regulate or prohibit, without necessarily reflecting what people actually did or refrained from doing.[27]

Major Latin authors whose works contribute significantly to an understanding of Roman sexuality include:

- the comic playwright Plautus (d. 184 BC), whose plots often revolve around sex comedy and young lovers kept apart by circumstances;

- the statesman and moralist Cato the Elder (d. 149 BC), who offers glimpses of sexuality at a time that later Romans regarded as having higher moral standards;

- the poet Lucretius (d. c. 55 BC), who presents an extended treatment of Epicurean sexuality in his philosophical work De rerum natura;

- Catullus (fl. 50s BC), whose poems explore a range of erotic experience near the end of the Republic, from delicate romanticism to brutally obscene invective;

- Cicero (d. 43 BC), with courtroom speeches that often attack the opposition's sexual conduct and letters peppered with gossip about Rome's elite;

- the Augustan elegists Propertius and Tibullus, who reveal social attitudes in describing love affairs with mistresses;

- Ovid (d. 17 AD), especially his Amores ("Love Affairs") and Ars Amatoria ("Art of Love"), which according to tradition contributed to Augustus's decision to exile the poet, and his epic, the Metamorphoses, which presents a range of sexuality, with an emphasis on rape, through the lens of mythology;

- the epigrammatist Martial (d. c. 102/4 AD), whose observations of society are braced by sexually explicit invective;

- the satirist Juvenal (d. early 2nd century AD), who rails against the sexual mores of his time.

Ovid lists a number of writers known for salacious material whose works are now lost.[28] Greek sex manuals and "straightforward pornography"[29] were published under the name of famous heterai (courtesans), and circulated in Rome. The robustly sexual Milesiaca of Aristides was translated by Sisenna, one of the praetors of 78 BC. Ovid calls the book a collection of misdeeds (crimina), and says the narrative was laced with dirty jokes.[30] After the Battle of Carrhae, the Parthians were reportedly shocked to find the Milesiaca in the baggage of Marcus Crassus's officers.[31]

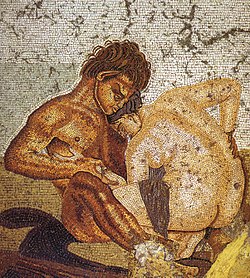

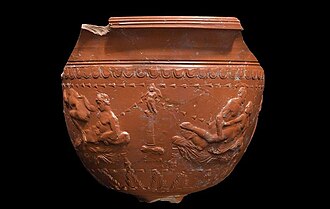

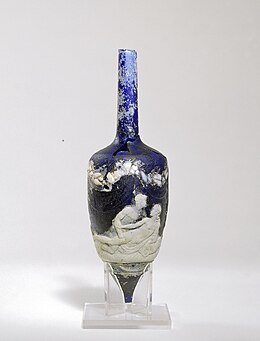

Erotic art, especially as preserved in Pompeii and Herculaneum, is a rich if not unambiguous source; some images contradict sexual preferences stressed in literary sources and may be intended to provoke laughter or challenge conventional attitudes.[32] Everyday objects such as mirrors and serving vessels might be decorated with erotic scenes; on Arretine ware, these range from "elegant amorous dalliance" to explicit views of the penis entering the vagina.[33] Erotic paintings were found in the most respectable houses of the Roman nobility, as Ovid notes:

Just as venerable figures of men, painted by the hand of an artist, are resplendent in our houses, so too there is a small painting (tabella)[n 1] in some spot which depicts various couplings and sexual positions: just as Telamonian Ajax sits with an expression that declares his anger, and the barbarian mother (Medea) has crime in her eyes, so too a wet Venus dries her dripping hair with her fingers and is viewed barely covered by the maternal waters.[34]

The pornographic tabella and the erotically charged Venus appear among various images that a connoisseur of art might enjoy.[35] A series of paintings from the Suburban Baths at Pompeii, discovered in 1986 and published in 1995, presents erotic scenarios that seem intended "to amuse the viewer with outrageous sexual spectacle," including a variety of positions, oral sex, and group sex featuring male–female, male–male, and female–female relations.[36]

The décor of a Roman bedroom could reflect quite literally its sexual use: the Augustan poet Horace supposedly had a mirrored room for sex, so that when he hired a prostitute he could watch from all angles.[37] The emperor Tiberius had his bedrooms decorated with "the most lascivious" paintings and sculptures, and stocked with Greek sex manuals by Elephantis in case those employed in sex needed direction.[38]

In the 2nd century AD, "there is a boom in texts about sex in Greek and Latin," along with romance novels.[39] But frank sexuality all but disappears from literature thereafter, and sexual topics are reserved for medical writing or Christian theology. In the 3rd century, celibacy had become an ideal among the growing number of Christians, and Church Fathers such as Tertullian and Clement of Alexandria debated whether even marital sex should be permitted for procreation. The sexuality of martyrology focuses on tests against the Christian's chastity[39] and sexual torture; Christian women are more often than men subjected to sexual mutilation, in particular of the breasts.[n 2] The obscene humor of Martial was briefly revived in 4th-century Bordeaux by the Gallo-Roman scholar-poet Ausonius, although he shunned Martial's predilection for pederasty and was at least nominally a Christian.[40]

Sex, religion, and the state

Like other aspects of Roman life, sexuality was supported and regulated by religious traditions, both the public cult of the state and private religious practices and magic. Sexuality was an important category of Roman religious thought.[42] The complement of male and female was vital to the Roman concept of deity. The Dii Consentes were a council of deities in male–female pairs, to some extent Rome's equivalent to the Twelve Olympians of the Greeks.[43] At least two state priesthoods were held jointly by a married couple.[n 3] The Vestal Virgins, the one state priesthood reserved for women, took a vow of chastity that granted them relative independence from male control; among the religious objects in their keeping was a sacred phallus:[44] "Vesta's fire ... evoked the idea of sexual purity in the female" and "represented the procreative power of the male".[45] The men who served in the various colleges of priests were expected to marry and have families. Cicero held that the desire (libido) to procreate was "the seedbed of the republic", as it was the cause for the first form of social institution, marriage. Marriage produced children and in turn a "house" (domus) for family unity that was the building block of urban life.[46]

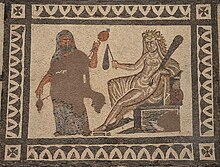

Many Roman religious festivals had an element of sexuality. The February Lupercalia, celebrated as late as the 5th century of the Christian era, included an archaic fertility rite. The Floralia featured nude dancing. At certain religious festivals throughout April, prostitutes participated or were officially recognized. Cupid inspired desire; the imported god Priapus represented gross or humorous lust; Mutunus Tutunus promoted marital sex. The god Liber (understood as the "Free One") oversaw physiological responses during sexual intercourse. When a male assumed the toga virilis, "toga of manhood," Liber became his patron; according to the love poets, he left behind the innocent modesty (pudor) of childhood and acquired the sexual freedom (libertas) to begin his course of love.[47] A host of deities oversaw every aspect of intercourse, conception, and childbirth.[48]

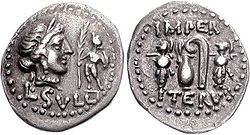

The connections among human reproduction, general prosperity, and the wellbeing of the state are embodied by the Roman cult of Venus, who differs from her Greek counterpart Aphrodite in her role as a mother of the Roman people through her half-mortal son Aeneas.[49] During the civil wars of the 80s BC, Sulla, about to invade his own country with the legions under his command, issued a coin depicting a crowned Venus as his personal patron deity, with Cupid holding a palm branch of victory; on the reverse military trophies flank symbols of the augurs, the state priests who read the will of the gods. The iconography links deities of love and desire with military success and religious authority; Sulla adopted the title Epaphroditus, "Aphrodite's own", before he became a dictator.[50] The fascinum, a phallic charm, was ubiquitous in Roman culture, appearing on everything from jewelry to bells and wind chimes to lamps,[51] including as an amulet to protect children[52] and triumphing generals.[53]

Classical myths often deal with sexual themes such as gender identity, adultery, incest, and rape. Roman art and literature continued the Hellenistic treatment of mythological figures having sex as humanly erotic and at times humorous, often removed from the religious dimension.[54]

Moral and legal concepts

Castitas

The Latin word castitas, from which the English "chastity" derives, is an abstract noun denoting "a moral and physical purity usually in a specifically religious context", sometimes but not always referring to sexual chastity.[55] The related adjective castus (feminine casta, neuter castum), "pure", can be used of places and objects as well as people; the adjective pudicus ("chaste, modest") describes more specifically a person who is sexually moral.[55] The goddess Ceres was concerned with both ritual and sexual castitas, and the torch carried in her honor as part of the Roman wedding procession was associated with the bride's purity; Ceres also embodied motherhood.[56] The goddess Vesta was the primary deity of the Roman pantheon associated with castitas, and a virgin goddess herself; her priestesses the Vestals were virgins who took a vow to remain celibate.

Incestum

Incestum (that which is "not castum") is an act that violates religious purity,[55] perhaps synonymous with that which is nefas, religiously impermissible.[57] The violation of a Vestal's vow of chastity was incestum, a legal charge brought against her and the man who rendered her impure through sexual relations, whether consensually or by force. A Vestal's loss of castitas ruptured Rome's treaty with the gods (pax deorum),[58] and was typically accompanied by the observation of bad omens (prodigia). Prosecutions for incestum involving a Vestal often coincide with political unrest, and some charges of incestum seem politically motivated;[59] for example, Marcus Crassus was acquitted of incestum with a Vestal who shared his family name, and in 113 BC there was a trial involving three vestal virgins and a network of Roman elite.[n 4] Although the English word "incest" derives from the Latin, incestuous relations are only one form of Roman incestum,[55] sometimes translated as "sacrilege". When Clodius Pulcher dressed as a woman and intruded on the all-female rites of the Bona Dea, he was charged with incestum.[60]

Stuprum

In Latin legal and moral discourse, stuprum is illicit sexual intercourse, translatable as "criminal debauchery"[61] or "sex crime".[62] Stuprum encompasses diverse sexual offenses including incestum, rape ("unlawful sex by force"),[63] and adultery. In early Rome, stuprum was a disgraceful act in general, or any public disgrace, including but not limited to illicit sex.[n 5] By the time of the comic playwright Plautus (ca. 254–184 BC) it had acquired its more restricted sexual meaning.[64] Stuprum can occur only among citizens; protection from sexual misconduct was among the legal rights that distinguished the citizen from the non-citizen.[64] Although the noun stuprum may be translated into English as fornication, the intransitive verb "to fornicate" is an inadequate translation of the Latin stuprare, which is a transitive verb requiring a direct object (the person who is the target of the misconduct) and a male agent (the stuprator).[64]

Raptus

The English word "rape" derives ultimately from the Latin verb rapio, rapere, raptus, "to snatch, carry away, abduct" (cf. English rapt, rapture, and raptor). In Roman law, raptus or raptio meant primarily kidnapping or abduction;[65] the mythological rape of the Sabine women is a form of bride abduction in which sexual violation is a secondary issue. The "abduction" of an unmarried girl from her father's household at times might be a matter of the couple eloping without her father's permission to marry. Rape in the English sense was more often expressed as stuprum committed through violence or coercion (cum vi or per vim). As laws pertaining to violence were codified toward the end of the Republic, raptus ad stuprum, "abduction for the purpose of committing a sex crime", emerged as a legal distinction.[66] (See further discussion of rape under "The rape of men" and "Rape and the law" below.)

Healing and magic

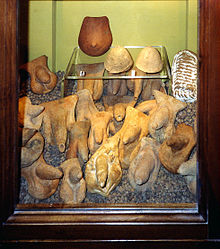

Divine aid might be sought in private religious rituals along with medical treatments to enhance or block fertility, or to cure diseases of the reproductive organs. Votive offerings (vota; compare ex-voto) in the form of breasts and penises have been found at healing sanctuaries.

A private ritual under some circumstances might be considered "magic", an indistinct category in antiquity.[67] An amatorium (Greek philtron) was a love charm or potion;[68] binding spells (defixiones) were supposed to "fix" a person's sexual affection.[69] The Greek Magical Papyri, a collection of syncretic magic texts, contain many love spells that indicate "there was a very lively market in erotic magic in the Roman period", catered by freelance priests who at times claimed to derive their authority from the Egyptian religious tradition.[70] Canidia, a witch described by Horace, performs a spell using a female effigy to dominate a smaller male doll.[71]

Aphrodisiacs, anaphrodisiacs, contraceptives, and abortifacients are preserved by both medical handbooks and magic texts; potions can be difficult to distinguish from pharmacology. In his Book 33 De medicamentis, Marcellus of Bordeaux, a contemporary of Ausonius,[72] collected more than 70 sexually related treatments—for growths and lesions on the testicles and penis, undescended testicles, erectile dysfunction, hydrocele, "creating a eunuch without surgery",[73] ensuring a woman's fidelity, and compelling or diminishing a man's desire—some of which involve ritual procedures:

If you’ve had a woman, and you don't want another man ever to get inside her, do this: Cut off the tail of a live green lizard with your left hand and release it while it’s still alive. Keep the tail closed up in the palm of the same hand until it dies and touch the woman and her private parts when you have intercourse with her.[74]

There is an herb called nymphaea in Greek, 'Hercules’ club' in Latin, and baditis in Gaulish. Its root, pounded to a paste and drunk in vinegar for ten consecutive days, turns a boy into a eunuch.[75]

If the spermatic veins of an immature boy should become enlarged (varicocele), split a young cherry-tree down the middle to its roots while leaving it standing, in such a way that the boy can be passed through the cleft. Then join the sapling together again and seal it with cow manure and other dressings, so that the parts that were split may intermingle within themselves more easily. The speed with which the sapling grows together and its scar forms will determine how quickly the swollen veins of the boy will return to health.[76]

Marcellus also records which herbs[77] could be used to induce menstruation, or to purge the womb after childbirth or abortion; these herbs include potential abortifacients and may have been used as such.[78] Other sources advise remedies such as coating the penis with a mixture of honey and pepper to get an erection,[79] or boiling an ass' genitals in oil as an ointment.[80]

Theories of sexuality

Ancient theories of sexuality were produced by and for an educated elite. The extent to which theorizing about sex actually affected behavior is debatable, even among those who were attentive to the philosophical and medical writings that presented such views. This elite discourse, while often deliberately critical of common or typical behaviors, at the same time cannot be assumed to exclude values broadly held within the society.

Epicurean sexuality

"Nor does he who avoids love lack the fruit of Venus but rather chooses goods which are without a penalty; for certainly the pleasure from this is more pure for the healthy than for the wretched. For indeed, at the very moment of possession, the hot passion of lovers fluctuates with uncertain wanderings and they are undecided what to enjoy first with eyes and hands. They tightly press what they have sought and cause bodily pain, and often drive their teeth into little lips and give crushing kisses, because the pleasure is not pure and there are goads underneath which prod them to hurt that very thing, whatever it is, from which those of frenzy spring."[81]

Lucretius, De rerum natura 4.1073–1085

The fourth book of Lucretius' De rerum natura provides one of the most extended passages on human sexuality in Latin literature. Yeats, describing the translation by Dryden, called it "the finest description of sexual intercourse ever written."[82] Lucretius was the contemporary of Catullus and Cicero in the mid-1st century BC. His didactic poem De rerum natura is a presentation of Epicurean philosophy within the Ennian epic tradition of Latin poetry. Epicureanism is both materialist and hedonic. The highest good is pleasure, defined as the absence of physical pain and emotional distress.[83] The Epicurean seeks to gratify his desires with the least expenditure of passion and effort. Desires are ranked as those that are both natural and necessary, such as hunger and thirst; those that are natural but unnecessary, such as sex; and those that are neither natural nor necessary, including the desire to rule over others and glorify oneself.[84] It is within this context that Lucretius presents his analysis of love and sexual desire, which counters the erotic ethos of Catullus and influenced the love poets of the Augustan period.[85]

Lucretius treats male desire, female sexual pleasure, heredity, and infertility as aspects of sexual physiology. In the Epicurean view, sexuality arises from impersonal physical causes without divine or supernatural influence. The onset of physical maturity generates semen, and wet dreams occur as the sexual instinct develops.[86][87] Sense perception, specifically the sight of a beautiful body, provokes the movement of semen into the genitals and toward the object of desire. The engorgement of the genitals creates an urge to ejaculate, coupled with the anticipation of pleasure. The body's response to physical attractiveness is automatic, and neither the character of the person desired nor one's own choice is a factor. With a combination of scientific detachment and ironic humor, Lucretius treats the human sex drive as muta cupido, "dumb desire", comparing the physiological response of ejaculation to the blood spurting from a wound.[88] Love (amor) is merely an elaborate cultural posturing that obscures a glandular condition;[89] love taints sexual pleasure just as life is tainted by the fear of death.[90] Lucretius is writing primarily for a male audience, and assumes that love is a male passion, directed at either boys or women.[91][92] Male desire is viewed as pathological, frustrating, and violent.[93]

Lucretius thus expresses an Epicurean ambivalence toward sexuality, which threatens one's peace of mind with agitation if desire becomes a form of bondage and torment,[94] but his view of female sexuality is less negative.[93] While men are driven by unnatural expectations to engage in onesided and desperate sex, women act on a purely animal instinct toward affection, which leads to mutual satisfaction.[95] The comparison with female animals in heat is meant not as an insult, though there are a few traces of conventional misogyny in the work, but to indicate that desire is natural and should not be experienced as torture.[95]

Having analyzed the sex act, Lucretius then considers conception and what in modern terms would be called genetics. Both man and woman, he says, produce genital fluids that mingle in a successful procreative act. The characteristics of the child are formed by the relative proportions of the mother's "seed" to the father's. A child who most resembles its mother is born when the female seed dominates the male's, and vice versa; when neither the male nor female seed dominates, the child will have traits of both mother and father evenly. The sex of the child, however, is not determined by the gender of the parent whose traits dominate. Infertility occurs when the two partners fail to make a satisfactory match of their seed after several attempts; the explanation for infertility is physiological and rational, and has nothing to do with the gods.[94][96] The transfer of genital "seed" (semina) is consonant with Epicurean physics and the theme of the work as a whole: the invisible semina rerum, "seeds of things," continually dissolve and recombine in universal flux.[97] The vocabulary of biological procreation thus underlies Lucretius' presentation of how matter is formed from atoms.[98]

Lucretius' purpose is to correct ignorance and to give the knowledge necessary for managing one's sex life rationally.[99] He distinguishes between pleasure and conception as goals of copulation; both are legitimate, but require different approaches.[99] He recommends casual sex as a way of releasing sexual tension without becoming obsessed with a single object of desire;[100][101] a "streetwalking Venus"—a common prostitute—should be used as a surrogate.[102] Sex without passionate attachment produces a superior form of pleasure free of uncertainty, frenzy, and mental disturbance.[103][104] Lucretius calls this form of sexual pleasure venus, in contrast to amor, passionate love.[105][106] The best sex is that of happy animals, or of gods.[107] Lucretius combines an Epicurean wariness of sex as a threat to peace of mind with the Roman cultural value placed on sexuality as an aspect of marriage and family life,[108] pictured as an Epicurean man in a tranquil and friendly marriage with a good but homely woman, beauty being a disquieting prompt to excessive desire.[109] Lucretius reacts against the Roman tendency to display sex ostentatiously, as in erotic art, and rejects the aggressive, "Priapic" model of sexuality spurred by visual stimulus.[110]

Stoic sexual morality

In early Stoicism among the Greeks, sex was regarded as a good, if enjoyed between people who maintained the principles of respect and friendship; in the ideal society, sex should be enjoyed freely, without bonds of marriage that treated the partner as property. Some Greek Stoics privileged same-sex relations between a man and a younger male partner[111][112] (see "Pederasty in ancient Greece"). However, Stoics in the Roman Imperial era departed from the view of human beings as "communally sexual animals"[113] and emphasized sex within marriage,[111] which as an institution helped sustain social order.[114] Although they distrusted strong passions, including sexual desire,[115] sexual vitality was necessary for procreation.

Roman-era Stoics such as Seneca and Musonius Rufus, both active about 100 years after Lucretius, emphasized "sex unity" over the polarity of the sexes.[116] Although Musonius is predominately a Stoic, his philosophy also partakes of Platonism and Pythagoreanism.[117] He rejected the Aristotelian tradition, which portrayed sexual dimorphism as expressing a proper relation of those ruling (male) and those being ruled (female), and distinguished men from women as biologically lacking. Dimorphism exists, according to Musonius, simply to create difference, and difference in turn creates the desire for a complementary relationship, that is, a couple who will bond for life for the sake of each other and for their children.[18] The Roman ideal of marriage was a partnership of companions who work together to produce and rear children, manage everyday affairs, lead exemplary lives, and enjoy affection; Musonius drew on this ideal to promote the Stoic view that the capacity for virtue and self-mastery was not gender-specific.[118]

Both Musonius and Seneca criticized the double standard, cultural and legal, that granted Roman men greater sexual freedom than women.[18][119] Men, Musonius argues, are excused by society for resorting to prostitutes and slaves to satisfy their sexual appetites, while such behavior from a woman would not be tolerated; therefore, if men presume to exercise authority over women because they believe themselves to have greater self-control, they ought to be able to manage their sex drive. The argument, then, is not that sexual freedom is a human good, but that men as well as women should exercise sexual restraint.[18][120] A man visiting a prostitute does harm to himself by lacking self-discipline; disrespect for his wife and her expectations of fidelity would not be an issue.[121] Similarly, a man should not be so self-indulgent as to exploit a female slave sexually; however, her right not to be used is not a motive for his restraint.[122] Musonius maintained that even within marriage, sex should be undertaken as an expression of affection and for procreation, and not for "bare pleasure".[123]

Musonius disapproved of same-sex relations because they lacked a procreative purpose.[18][124] Seneca and Epictetus also thought that procreation privileged male–female sexual pairing within marriage.[125]

Although Seneca is known primarily as a Stoic philosopher, he draws on Neopythagoreanism for his views on sexual austerity.[126] Neopythagoreans characterized sexuality outside marriage as disordered and undesirable; celibacy was not an ideal, but chastity within marriage was.[127] To Seneca, sexual desire for pleasure (libido) is a "destructive force (exitium) insidiously fixed in the innards"; unregulated, it becomes cupiditas, lust. The only justification for sex is reproduction within marriage.[128] Although other Stoics see potential in beauty to be an ethical stimulus, a way to attract and develop affection and friendship within sexual relations, Seneca distrusts the love of physical beauty as destroying reason to the point of insanity.[129] A man should have no sexual partner other than his wife;[126] Seneca strongly opposed adultery, finding it particularly offensive by women.[130] The wise man (sapiens, Greek sophos) will make love to his wife by exercising good judgment (iudicium), not emotion (affectus).[131] This is a far stricter view than that of other Stoics who advocate sex as a means of promoting mutual affection within marriage.[131]

The philosophical view of the body as a corpse that carries around the soul[132] could result in outright contempt for sexuality: the emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius writes, "as for sexual intercourse, it is the friction of a piece of gut and, following a sort of convulsion, the expulsion of some mucus".[133] Seneca rails "at great length" against the perversity of one Hostius Quadra, who surrounded himself with the equivalent of funhouse mirrors so he could view sex parties from distorted angles and penises would look bigger.[134]

Sexual severity opened the Roman Stoics to charges of hypocrisy: Juvenal satirizes those who affect a rough and manly Stoic façade but privately indulge.[135] It was routinely joked that not only were Stoics inclined toward pederasty, they liked young men who were acquiring beards, contrary to Roman sexual custom.[111] Martial repeatedly makes insinuations about those who were outwardly Stoic but privately enjoyed the passive homosexual role.[136]

Stoic sexual ethics are grounded in their physics and cosmology.[137] The 5th-century writer Macrobius preserves a Stoic interpretation of the myth of the birth of Venus as a result of the primal castration of the deity Heaven (Latin Caelus).[n 6] The myth, Macrobius indicates, could be understood as an allegory of the doctrine of seminal reason. The elements derive from the semina, "seeds," that are generated by heaven; "love" brings together the elements in the act of creation, like the sexual union of male and female.[138] Cicero suggests that in Stoic allegory the severing of reproductive organs signifies "that the highest heavenly aether, that seed-fire which generates all things, did not require the equivalent of human genitals to proceed in its generative work".[139]

Male sexuality

During the Republic, a Roman citizen's political liberty (libertas) was defined in part by the right to preserve his body from physical compulsion, including both corporal punishment and sexual abuse.[140] Virtus, "valor" as that which made a man most fully a man (vir), was among the active virtues.[141][142][143] Roman ideals of masculinity were thus premised on taking an active role that was also, as Williams has noted, "the prime directive of masculine sexual behavior for Romans." The impetus toward action might express itself most intensely in an ideal of dominance that reflects the hierarchy of Roman patriarchal society.[144] The "conquest mentality" was part of a "cult of virility" that particularly shaped Roman homosexual practices.[145][19] In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, an emphasis on domination has led scholars to view expressions of Roman male sexuality in terms of a "penetrator-penetrated" binary model; that is, the proper way for a Roman male to seek sexual gratification was to insert his penis in his partner.[20] Allowing himself to be penetrated threatened his liberty as a free citizen as well as his sexual integrity.[n 7]

It was expected and socially acceptable for a freeborn Roman man to want sex with both female and male partners, as long as he took the dominating role.[146] Acceptable objects of desire were women of any social or legal status, male prostitutes, or male slaves, but sexual behaviors outside marriage were to be confined to slaves and prostitutes, or less often a concubine or "kept woman." Lack of self-control, including in managing one's sex life, indicated that a man was incapable of governing others;[147] the enjoyment of "low sensual pleasure" threatened to erode the elite male's identity as a cultured person.[148] It was a point of pride for Gaius Gracchus to claim that during his term as a provincial governor he kept no slave-boys chosen for their good looks, no female prostitutes visited his house, and he never accosted other men's slave-boys.[149][150]

In the Imperial era, anxieties about the loss of political liberty and the subordination of the citizen to the emperor were expressed by a perceived increase in passive homosexual behavior among free men, accompanied by a documentable increase in the execution and corporal punishment of citizens.[151] The dissolution of Republican ideals of physical integrity in relation to libertas contributes to and is reflected by the sexual license and decadence associated with the Empire.[152]

Male nudity

The poet Ennius (ca. 239–169 BC) declared that "exposing naked bodies among citizens is the beginning of public disgrace (flagitium)," a sentiment echoed by Cicero that again links the self-containment of the body with citizenship.[153][154][155][156] Roman attitudes toward nudity differed from those of the Greeks, whose ideal of masculine excellence was expressed by the nude male body in art and in such real-life venues as athletic contests. The toga, by contrast, distinguished the body of the sexually privileged adult Roman male.[157] Even when stripping down for exercises, Roman men kept their genitals and buttocks covered, an Italic custom shared also with the Etruscans, whose art mostly shows them wearing a loincloth, a skirt-like garment, or the earliest form of "shorts" for athletics. Romans who competed in the Olympic Games presumably followed the Greek custom of nudity, but athletic nudity at Rome has been dated variously, possibly as early as the introduction of Greek-style games in the 2nd century BC but perhaps not regularly till the time of Nero around 60 AD.[158]

Public nudity might be offensive or distasteful even in traditional settings; Cicero derides Mark Antony as undignified for appearing near-naked as a participant in the Lupercalia, even though it was ritually required.[159][160] Nudity is one of the themes of this religious festival that most consumes Ovid's attention in the Fasti, his long-form poem on the Roman calendar.[161] Augustus, during his program of religious revivalism, attempted to reform the Lupercalia, in part by suppressing the use of nudity despite its fertility aspect.[162]

Negative connotations of nudity include defeat in war, since captives were stripped, and slavery, since slaves for sale were often displayed naked. The disapproval of nudity was thus less a matter of trying to suppress inappropriate sexual desire than of dignifying and marking the citizen's body as free.[163]

The influence of Greek art, however, led to "heroic" nude portrayals of Roman men and gods, a practice that began in the 2nd century BC. When statues of Roman generals nude in the manner of Hellenistic kings first began to be displayed, they were shocking not simply because they exposed the male figure, but because they evoked concepts of royalty and divinity that were contrary to Republican ideals of citizenship as embodied by the toga.[164]

The god Mars is presented as a mature, bearded man in the attire of a Roman general when he is conceived of as the dignified father of the Roman people, while depictions of Mars as youthful, beardless, and nude show the influence of the Greek Ares. In art produced under Augustus, the programmatic adoption of Hellenistic and Neo-Attic style led to more complex signification of the male body shown nude, partially nude, or costumed in a muscle cuirass.[165]

One exception to public nudity was the baths, though attitudes toward nude bathing also changed over time. In the 2nd century BC, Cato preferred not to bathe in the presence of his son, and Plutarch implies that for Romans of these earlier times it was considered shameful for mature men to expose their bodies to younger males.[166][163][167] Later, however, men and women might even bathe together.[n 8]

Phallic sexuality

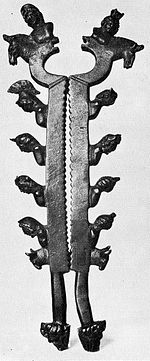

Roman sexuality as framed by Latin literature has been described as phallocentric.[168][169] The phallus was supposed to have powers to ward off the evil eye and other malevolent supernatural forces. It was used as an amulet (fascinum), many examples of which survive, particularly in the form of wind chimes (tintinnabula).[170] Some scholars have even interpreted the plan of the Forum Augustum as phallic, "with its two semi-circular galleries or exedrae as the testicles and its long projecting forecourt as the shaft".[171][172]

The outsized phallus of Roman art was associated with the god Priapus, among others. It was laughter-provoking, grotesque, or used for magical purposes.[173] Originating in the Greek town of Lampsacus, Priapus was a fertility deity whose statue was placed in gardens to ward off thieves. The poetry collection called the Priapea deals with phallic sexuality, including poems spoken in the person of Priapus. In one, for instance, Priapus threatens anal rape against any potential thief. The wrath of Priapus might cause impotence, or a state of perpetual arousal with no means of release: one curse of Priapus upon a thief was that he might lack women or boys to relieve him of his erection, and burst.[144]

There are approximately 120 recorded Latin terms and metaphors for the penis, with the largest category treating the male member as an instrument of aggression, a weapon.[174] This metaphorical tendency is exemplified by actual lead sling-bullets, which are sometimes inscribed with the image of a phallus, or messages that liken the target to a sexual conquest—for instance "I seek Octavian's asshole."[175] The most common obscenity for the penis is mentula, which Martial argues for in place of polite terms: his privileging of the word as time-honored Latin from the era of Numa may be compared to the unvarnished integrity of "four letter Anglo-Saxon words".[176][177] Cicero does not use the word even when discussing the nature of obscene language in a letter to his friend Atticus;[178][177] Catullus famously uses it as a pseudonym for the disreputable Mamurra, Julius Caesar's friend ("Dick" or "Peter" might be English equivalents).[179] Mentula appears frequently in graffiti and the Priapea,[180] but while obscene the word was not inherently abusive or vituperative. Verpa, by contrast, was "an emotive and highly offensive word" for the penis with its foreskin drawn back, as the result of an erection, excessive sexual activity, or circumcision.[181][182] Virga, as well as other words for "branch, rod, stake, beam", is a common metaphor,[183] as is vomer, "plough".[184]

The penis might also be referred to as the "vein" (vena), "tail" (penis or cauda), or "tendon" (nervus).[185] The English word "penis" derives from penis, which originally meant "tail" but in Classical Latin was used regularly as a risqué colloquialism for the male organ. Later, penis becomes the standard word in polite Latin, as used for example by the scholiast to Juvenal and by Arnobius, but did not pass into usage among the Romance languages.[186] It was not a term used by medical writers, except for Marcellus of Bordeaux.[187][188] In medieval Latin, a vogue for scholarly obscenity led to a perception of the dactyl, a metrical unit of verse represented — ‿ ‿, as an image of the penis, with the long syllable (longum) the shaft and the two short syllables (breves) the testicles.[189]

The apparent connection between Latin testes, "testicles," and testis, plural testes, "witness" (the origin of English "testify" and "testimony")[190] may lie in archaic ritual. Some ancient Mediterranean cultures swore binding oaths upon the male genitalia, symbolizing that "the bearing of false witness brings a curse upon not only oneself, but one's house and future line".[191] Latin writers make frequent puns and jokes based on the two meanings of testis:[192] it took balls to become a legally functioning male citizen.[193] The English word "testicle" derives from the diminutive testiculum.[192] The obscene word for "testicle" was coleus,[194] from which descends French couille.

Castration and circumcision

To Romans and Greeks, castration and circumcision were linked as barbaric mutilations of the male genitalia.[182][195][196][197][198][199][200] When the cult of Cybele was imported to Rome at the end of the 3rd century BC, its traditional eunuchism was confined to foreign priests (the Galli), while Roman citizens formed sodalities to perform honors in keeping with their own customs.[201] It has been argued that the Apostle Paul's exhortation of the Galatians not to undergo circumcision[202][203][204] should be understood not only in the context of Jewish circumcision, but also of the ritual castration associated with Cybele, whose cult was centered in Galatia.[205][206][207] Among Jews, circumcision was a marker of the Abrahamic covenant; diaspora Jews circumcised their male slaves and adult male converts, in addition to Jewish male infants.[208] Although Greco-Roman writers view circumcision as an identifying characteristic of Jews, they believed the practice to have originated in Egypt,[182][209] and recorded it among peoples they identified as Arab, Syrian, Phoenician, Colchian, and Ethiopian.[210][211] The Neoplatonic philosopher Sallustius associates circumcision with the strange familial–sexual customs of the Massagetae who "eat their fathers" and of the Persians who "preserve their nobility by begetting children on their mothers".[212]

During the Republican period, a Lex Cornelia prohibited various kinds of mutilation, including castration. (Two millennia later, in 1640, the poet Salvatore Rosa would write in La Musica, “Fine Cornelia law, where hast thou gone / Now that the whole of Norcia seems not enough / For the castration of boys?”)[215] Despite these prohibitions, some Romans kept beautiful male slaves as deliciae or delicati ("toys, delights") who were sometimes castrated in an effort to preserve the androgynous looks of their youth. The emperor Nero had his freedman Sporus castrated, and married him in a public ceremony.[216]

By the end of the 1st century AD, bans against castration had been enacted by the emperors Domitian and Nerva in the face of a burgeoning trade in eunuch slaves. Sometime between 128 and 132 AD, Hadrian seems to have temporarily banned circumcision, on pain of death.[217] Antoninus Pius exempted Jews from the ban,[218][219] as well as Egyptian priests,[220] and Origen says that in his time only Jews were permitted to practice circumcision.[221][222] Legislation under Constantine, the first Christian emperor, freed any slave who was subjected to circumcision; in 339 AD, circumcising a slave became punishable by death.[223]

A medical procedure known as epispasm, which consisted of both surgical and non-surgical methods,[182][195][224] existed in ancient Rome and Greece to restore the foreskin and cover the glans "for the sake of decorum".[158][182][195][196][225] Both were described in detail by the Greek physician Aulus Cornelius Celsus in his comprehensive encyclopedic work De Medicina, written during the reign of Tiberius (14–37 CE).[195][224] The surgical method involved freeing the skin covering the penis by dissection, and then pulling it forward over the glans; he also described a simpler surgical technique used on men whose prepuce is naturally insufficient to cover their glans.[195][196][224] The second approach was non-surgical: a restoration device which consisted of a special weight made of bronze, copper, or leather, was affixed to the penis, pulling its skin downward.[195][224] Over time a new foreskin was generated, or a short prepuce was lengthened, by means of tissue expansion;[195][224] Martial also mentioned the restoration device in his epigrams (7:35).[224] Hellenized or Romanized Jews resorted to epispasm to better integrate into Greco–Roman society, and also to make themselves less conspicuous at the baths or during athletics.[182][195][197] Of these, some had themselves circumcised again later.[226]

Regulating semen

Too-frequent ejaculation was thought to weaken men. Greek medical theories based on the classical elements and humors recommended limiting the production of semen by means of cooling, drying, and astringent therapies, including cold baths and the avoidance of flatulence-causing foods.[227] In the 2nd century AD, the medical writer Galen explains semen as a concoction of blood (conceived of as a humor) and pneuma (the "vital air" required by organs to function) formed within the man's coiled spermatic vessels, with the humor turning white through heat as it enters into the testicles.[228] In his treatise On Semen, Galen warns that immoderate sexual activity results in a loss of pneuma and hence vitality:

It is not at all surprising that those who are less moderate sexually turn out to be weaker, since the whole body loses the purest part of both substances, and there is besides an accession of pleasure, which by itself is enough to dissolve the vital tone, so that before now some persons have died from excess of pleasure.[229]

The uncontrolled dispersing of pneuma in semen could lead to loss of physical vigor, mental acuity, masculinity, and a strong manly voice,[230] a complaint registered also in the Priapea.[231] Sexual activity was thought particularly to affect the voice: singers and actors might be infibulated to preserve their voices.[232][233][234] Quintilian advises that the orator who wished to cultivate a deep masculine voice for court should abstain from sexual relations.[235] This concern was felt intensely by Catullus's friend Calvus, the 1st-century BC avant-garde poet and orator, who slept with lead plates over his kidneys to control wet dreams. Pliny reports that:

When plates of lead are bound to the area of the loins and kidneys, it is used, owing to its rather cooling nature, to check the attacks of sexual desire and sexual dreams in one's sleep that cause spontaneous eruptions to the point of becoming a sort of disease. With these plates the orator Calvus is reported to have restrained himself and to have preserved his body's strength for the labor of his studies.[236]

Lead plates, cupping therapy, and hair removal were prescribed for three sexual disorders thought to be related to nocturnal emissions: satyriasis, or hypersexuality; priapism, a chronic erection without an accompanying desire for sex; and the involuntary discharge of semen (seminis lapsus or seminis effusio).[237]

Effeminacy and transvestism

Effeminacy was a favorite accusation in Roman political invective, and was aimed particularly at populares, the politicians of the faction who represented themselves as champions of the people, sometimes called Rome's "democratic" party in contrast to the optimates, a conservative elite of nobles.[238] In the last years of the Republic, the popularists Julius Caesar, Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony), and Clodius Pulcher, as well as the Catilinarian conspirators, were all derided as effeminate, overly-groomed, too-good-looking men who might be on the receiving end of sex from other males; at the same time, they were supposed to be womanizers or possessed of devastating sex appeal.[239]

Perhaps the most notorious incident of cross-dressing in ancient Rome occurred in 62 BC, when Clodius Pulcher intruded on annual rites of the Bona Dea that were restricted to women only. The rites were held at a senior magistrate's home, in this year that of Julius Caesar, nearing the end of his term as praetor and only recently invested as Pontifex Maximus. Clodius disguised himself as a female musician to gain entrance, as described in a "verbal striptease" by Cicero, who prosecuted him for sacrilege (incestum):[240]

Take away his saffron dress, his tiara, his girly shoes and purple laces, his bra, his Greek harp, take away his shameless behavior and his sex crime, and Clodius is suddenly revealed as a democrat.[241]

The actions of Clodius, who had just been elected quaestor and was probably about to turn thirty, are often regarded as a last juvenile prank. The all-female nature of these nocturnal rites attracted much prurient speculation from men; they were fantasized as drunken lesbian orgies that might be fun to watch.[242] Clodius is supposed to have intended to seduce Caesar's wife, but his masculine voice gave him away before he got a chance. The scandal prompted Caesar to seek an immediate divorce to control the damage to his own reputation, giving rise to the famous line "Caesar's wife must be above suspicion". The incident "summed up the disorder of the final years of the republic".[243][244]

In addition to political invective, cross-dressing appears in Roman literature and art as a mythological trope (as in the story of Hercules and Omphale exchanging roles and attire),[245] religious investiture, and rarely or ambiguously as transvestic fetishism. A section of the Digest by Ulpian[246] categorizes Roman clothing on the basis of who may appropriately wear it; a man who wore women's clothes, Ulpian notes, would risk making himself the object of scorn. A fragment from the playwright Accius (170–86 BC) seems to refer to a father who secretly wore "virgin's finery".[247] An instance of transvestism is noted in a legal case, in which "a certain senator accustomed to wear women's evening clothes" was disposing of the garments in his will.[248] In a "mock trial" exercise presented by the elder Seneca, a young man (adulescens) is gang-raped while wearing women's clothes in public, but his attire is explained as his acting on a dare by his friends, not as a choice based on gender identity or the pursuit of erotic pleasure.[249][250]

Gender ambiguity was a characteristic of the priests of the goddess Cybele known as Galli, whose ritual attire included items of women's clothing. They are sometimes considered a transgender priesthood, since they were required to be castrated in imitation of Attis. The complexities of gender identity in the religion of Cybele and the Attis myth are explored by Catullus in one of his longest poems, Carmen 63.[251]

Male–male sex

Roman men were free to have sex with males of lower status with no perceived loss of masculine prestige, and indeed, sexual mastery and dominance of others - regardless of their sex - could even enhance their masculinity. However, those who took the receiving role in sex acts, sometimes referred to as the "passive" or "submissive" role, were disparaged as weak and effeminate (see the section below on cunnilungus and fellatio),[252] while having sex with males in the active position was proof of one's masculinity.[252] Physical mastery over other people was an aspect of the citizen's libertas, political liberty,[253] and that certainly included for the purpose of sexual gratification, whether that was with a woman or a man. On the other hand, allowing one's body to be subjugated for the pleasure of others, particularly for sexual purposes, was seen as degrading and a mark of weakness and servility. Laws such as the poorly understood Lex Scantinia and various pieces of Augustan moral legislation were meant to restrict same-sex activity among freeborn males, viewed as threatening a man's status and independence as a citizen.

Latin had such a wealth of words for men outside the masculine norm that some scholars[254] argue for the existence of a homosexual subculture at Rome; that is, although the noun "homosexual" has no straightforward equivalent in Latin and is an anachronism when applied to Roman culture, literary sources do reveal a pattern of behaviors among a minority of free men that indicate same-sex preference or orientation. Some terms, such as exoletus, specifically refer to an adult; Romans who were socially marked as "masculine" did not confine their same-sex penetration of male prostitutes or slaves to those who were "boys" under the age of 20.[255] The Satyricon, for example, includes many descriptions of adult, free men showing sexual interest in one another. Some older men may at times have preferred the passive role with a partner of the same age or younger, but this was socially frowned upon.

Homoerotic Latin literature includes the "Juventius" poems of Catullus,[256] elegies by Tibullus[257] and Propertius,[258] the second Eclogue of Vergil, and several poems by Horace. Lucretius addresses the love of boys in De rerum natura (4.1052–1056). The poet Martial, despite being married to a woman, often derides women as sexual partners, and celebrates the charms of pueri (boys).[259] The Satyricon of Petronius is so permeated with the culture of male–male sexuality that in 18th-century European literary circles, his name became "a byword for homosexuality".[260] Although Ovid includes mythological treatments of homoeroticism in the Metamorphoses,[261] he is unusual among Latin love poets, and indeed among Romans in general, for his aggressively heterosexual stance, though even he did not claim exclusive heterosexuality.[252]

Although Roman law did not recognize marriage between men, in the early Imperial period some male couples were celebrating traditional marriage rites. Same-sex weddings are reported by sources that mock them; the feelings of the participants are not recorded.[262][263]

Apart from measures to protect the liberty of citizens, the prosecution of homosexuality as a general crime began in the 3rd century when male prostitution was banned by Philip the Arab, a sympathizer of the Christian faith. By the end of the 4th century, passive homosexuality under the Christian Empire was punishable by burning.[264] "Death by sword" was the punishment for a "man coupling like a woman" under the Theodosian Code.[265] Under Justinian, all same-sex acts, passive or active, no matter who the partners, were declared contrary to nature and punishable by death.[266] Homosexual behaviors were pointed to as causes for God's wrath following a series of disasters around 542 and 559.[267] Justinian also demanded the penalty of death for anyone who enslaved a castrated Roman, although he permitted the buying and selling of foreign-born eunuchs as long as they were castrated outside the boundaries of the Roman Empire (Codex Justinianus, 4.42.2).[268]

The rape of men

Men who had been raped were exempt from the loss of legal or social standing (infamia) suffered by males who prostituted themselves or willingly took the receiving role in sex.[269] According to the jurist Pomponius, "whatever man has been raped by the force of robbers or the enemy in wartime (vi praedonum vel hostium)" ought to bear no stigma.[270] Fears of mass rape following a military defeat extended equally to male and female potential victims.[271]

Roman law addressed the rape of a male citizen as early as the 2nd century BC, when a ruling was issued in a case that may have involved a male of same-sex orientation. Although a man who had worked as a prostitute could not be raped as a matter of law, it was ruled that even a man who was "disreputable (famosus) and questionable (suspiciosus)" had the same right as other free men not to have his body subjected to forced sex.[272] In a book on rhetoric from the early 1st century BC, the rape of a freeborn male (ingenuus) is equated with that of a materfamilias as a capital crime.[273][274] The Lex Julia de vi publica,[275] recorded in the early 3rd century AD but "probably dating from the dictatorship of Julius Caesar", defined rape as forced sex against "boy, woman, or anyone"; the rapist was subject to execution, a rare penalty in Roman law.[276] It was a capital crime for a man to abduct a free-born boy for sexual purposes, or to bribe the boy's chaperone (comes) for the opportunity.[277] Negligent chaperones could be prosecuted under various laws, placing the blame on those who failed in their responsibilities as guardians rather than on the victim.[278] Although the law recognized the victim's blamelessness, rhetoric used by the defense indicates that attitudes of blame among jurors could be exploited.[250]

In his collection of twelve anecdotes dealing with assaults on chastity, the historian Valerius Maximus features male victims in equal number to female.[279][250] In the "mock trial" case described by the elder Seneca, an adulescens (a man young enough not to have begun his formal career) was gang-raped by ten of his peers; although the case is imaginary, Seneca assumes that the law permitted the successful prosecution of the rapists.[249] Another hypothetical case imagines the extremity to which a rape victim could be driven: the free-born male who was raped commits suicide.[280][281] The rape of an ingenuus is among the worst crimes that could be committed in Rome, along with parricide, the rape of a female virgin, and robbing a temple.[282] Rape was nevertheless one of the traditional punishments inflicted on a male adulterer by the wronged husband,[283] though perhaps more in revenge fantasy than in practice.[284] The threat of one man to subject another to anal or oral rape (irrumatio) is a theme of invective poetry, most notably in Catullus' notorious Carmen 16,[285] and was a form of masculine braggadocio.[286][287][288]

Sex in the military

The Roman soldier, like any free and respectable Roman male of status, was expected to show self-discipline in matters of sex. Soldiers convicted of adultery were given a dishonorable discharge; convicted adulterers were barred from enlisting. Strict commanders might ban prostitutes and pimps from camp,[289] though in general the Roman army, whether on the march or at a permanent fort (castrum), was attended by a number of camp followers who might include prostitutes. Their presence seems to have been taken for granted, and mentioned mainly when it became a problem;[289] for instance, when Scipio Aemilianus was setting out for Numantia in 133 BC, he dismissed the camp followers as one of his measures for restoring discipline.[290]

Perhaps most peculiar is the prohibition against marriage in the Imperial army. In the early period, Rome had an army of citizens who left their families and took up arms as the need arose. During the expansionism of the Middle Republic, Rome began acquiring vast territories to be defended as provinces, and during the time of Gaius Marius (d. 86 BC), the army had been professionalized. The ban on marriage began under Augustus (ruled 27 BC–14 AD), perhaps to discourage families from following the army and impairing its mobility. The marriage ban applied to all ranks up to the centurionate; men of the governing classes were exempt. By the 2nd century AD, the stability of the Empire kept most units in permanent forts, where attachments with local women often developed. Although legally these unions could not be formalized as marriages, their value in providing emotional support for the soldiers was recognized. After a soldier was discharged, the couple were granted the right of legal marriage as citizens (conubium), and any children they already had were considered to have been born to citizens.[291] Septimius Severus rescinded the ban in 197 AD.[292]

Other forms of sexual gratification available to soldiers were the use of male slaves, war rape, and same-sex relations.[293] Homosexual behavior among soldiers was subject to harsh penalties, including death,[289] as a violation of military discipline. Polybius (2nd century BC) reports that same-sex activity in the military was punishable by the fustuarium, clubbing to death.[294] Sex among fellow soldiers violated the Roman decorum against intercourse with another freeborn male. A soldier maintained his masculinity by not allowing his body to be used for sexual purposes. This physical integrity stood in contrast to the limits placed on his actions as a free man within the military hierarchy; most strikingly, Roman soldiers were the only citizens regularly subjected to corporal punishment, reserved in the civilian world mainly for slaves. Sexual integrity helped distinguish the status of the soldier, who otherwise sacrificed a great deal of his civilian autonomy, from that of the slave.[295] In warfare, rape signified defeat, another motive for the soldier not to compromise his body sexually.[296]

An incident related by Plutarch in his biography of Marius illustrates the soldier's right to maintain his sexual integrity. A good-looking young recruit named Trebonius[297] had been sexually harassed over a period of time by his superior officer, who happened to be Marius' nephew, Gaius Luscius. One night, having fended off unwanted advances on numerous occasions, Trebonius was summoned to Luscius' tent. Unable to disobey the command of his superior, he found himself the object of a sexual assault and drew his sword, killing Luscius. A conviction for killing an officer typically resulted in execution. When brought to trial, he was able to produce witnesses to show that he had repeatedly had to fend off Luscius, and "had never prostituted his body to anyone, despite offers of expensive gifts". Marius not only acquitted Trebonius in the killing of his kinsman, but gave him a crown for bravery.[298][299][300][301] Roman historians record other cautionary tales of officers who abuse their authority to coerce sex from their soldiers, and then suffer dire consequences.[302] The youngest officers, who still might retain some of the adolescent attraction that Romans favored in male–male relations, were advised to beef up their masculine qualities, such as not wearing perfume, nor trimming nostril and underarm hair.[303]

During wartime, the violent use of war captives for sex was not considered criminal rape.[304] Mass rape was one of the acts of punitive violence during the sack of a city,[305] but if the siege had ended through diplomatic negotiations rather than storming the walls, by custom the inhabitants were neither enslaved nor subjected to personal violence. Mass rape occurred in some circumstances, and is likely to be underreported in the surviving sources, but was not a deliberate or pervasive strategy for controlling a population.[306] An ethical ideal of sexual self-control among enlisted men was vital to preserving peace once hostilities ceased. In territories and provinces brought under treaty with Rome, soldiers who committed rape against the local people might be subjected to harsher punishments than civilians.[307] Sertorius, the long-time governor of Roman Spain whose policies emphasized respect and cooperation with provincials, executed an entire cohort when a single soldier had attempted to rape a local woman.[308][309] Mass rape seems to have been more common as a punitive measure during Roman civil wars than abroad.[310]

Female sexuality

Because of the Roman emphasis on family, female sexuality was regarded as one of the bases for social order and prosperity. Female citizens were expected to exercise their sexuality within marriage, and were honored for their sexual integrity (pudicitia) and fecundity: Augustus granted special honors and privileges to women who had given birth to three children (see "Ius trium liberorum"). Control of female sexuality was regarded as necessary for the stability of the state, as embodied most conspicuously in the absolute virginity of the Vestals.[311] A Vestal who violated her vow was entombed alive in a ritual that mimicked some aspects of a Roman funeral; her lover was executed.[312] Female sexuality, either disorderly or exemplary, often impacts state religion in times of crisis for the Republic.[313] The moral legislation of Augustus focused on harnessing the sexuality of women.

As was the case for men, free women who displayed themselves sexually, such as prostitutes and performers, or who made themselves available indiscriminately were excluded from legal protections and social respectability.[314]

Many Roman literary sources approve of respectable women exercising sexual passion within marriage.[315] While ancient literature overwhelmingly takes a male-centered view of sexuality, the Augustan poet Ovid expresses an explicit and virtually unique interest in how women experience intercourse.[316]

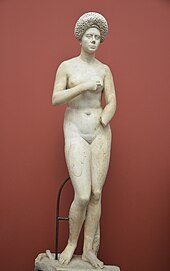

The female body

Roman attitudes toward female nudity differed from but were influenced by those of the Greeks, who idealized the male body in the nude while portraying respectable women clothed. Partial nudity of goddesses in Roman Imperial art, however, can highlight the breasts as dignified but pleasurable images of nurturing, abundance, and peacefulness.[160][317] Erotic art indicates that women with small breasts and wide hips had the ideal body type.[318][319] By the 1st century AD, Roman art shows a broad interest in the female nude engaged in varied activities, including sex.[320] Pornographic art that depicts women presumed to be prostitutes performing sex acts may show the breasts covered by a strophium even when the rest of the body is naked.

In the real world, as described in literature, prostitutes sometimes displayed themselves naked at the entrance to their brothel cubicles, or wore see-through silk garments; slaves for sale were often displayed naked to allow buyers to inspect them for defects, and to symbolize that they lacked the right to control their own body.[321][322] As Seneca the Elder described a woman for sale:

Naked she stood on the shore, at the pleasure of the purchaser; every part of her body was examined and felt. Would you hear the result of the sale? The pirate sold; the pimp bought, that he might employ her as a prostitute.[323]

The display of the female body made it vulnerable. Varro said sight was the greatest of the senses, because while the others were limited by proximity, sight could penetrate even to the stars; he thought the Latin word for "sight, gaze", visus, was etymologically related to vis, "force, power". But the connection between visus and vis, he said, also implied the potential for violation, just as Actaeon gazing on the naked Diana violated the goddess.[324][325]

The completely nude female body as portrayed in sculpture was thought to embody a universal concept of Venus, whose counterpart Aphrodite is the goddess most often depicted nude in Greek art.[326][327]

Female genitals

The "basic obscenity" for the female genitalia is cunnus, "cunt", though perhaps not as strongly offensive as the English.[328] Martial uses the word more than thirty times, Catullus once, and Horace thrice only in his early work; it also appears in the Priapea and graffiti.[329] One of the slang words women used for their genitals was porcus, "pig", particularly when mature women spoke of girls. Varro connects this usage of the word to the sacrifice of a pig to the goddess Ceres in preliminary wedding rites.[330] Metaphors of fields, gardens, and meadows are common, as is the image of the masculine "plough" in the feminine "furrow".[331] Other metaphors include cave, ditch, pit, bag, vessel, door, hearth, oven, and altar.[332]

Although women's genitals appear often in invective and satiric verse as objects of disgust, they are rarely referred to in Latin love elegy.[333] Ovid, the most heterosexual of the classic love poets, is the only one to refer to giving a woman pleasure through genital stimulation.[334] Martial writes of female genitalia only insultingly, describing one woman's vagina as "loose ... as the foul gullet of a pelican".[335][336] The vagina is often compared to a boy's anus as a receptacle for the phallus.[337][338]

The function of the clitoris (landica) was "well understood".[339] In classical Latin, landica was a highly indecorous obscenity found in graffiti and the Priapea; the clitoris was usually referred to with a metaphor, such as Juvenal's crista ("crest").[340][341] Cicero records that a hapless speaker of consular rank broke up the senate just by saying something that sounded like landica: hanc culpam maiorem an il-lam dicam? ("Shall I call this fault greater or that one?" heard as "this greater fault or a clitoris?"). "Could he have been more obscene?" Cicero exclaims, observing at the same time that cum nos, "when we", sounds like cunnus.[342][339][343] A lead sling-bullet uncovered through archaeology was inscribed "I aim for Fulvia's clit" (Fulviae landicam peto), Fulvia being the wife of Mark Antony who commanded troops during the civil wars of the 40s and 30s.[344]

Latin lacked a standard word for labia;[345] two terms found in medical writers are orae, "edges" or "shores",[346] and pinnacula, "little wings".[345] The first recorded instance of the word vulva occurs in Varro's work on agriculture (1st century BC), where it refers to the membrane that surrounds a fetus.[347][348] In the early Empire, vulva came into usage for "womb", the usual word for which had been uterus in the Republic, or sometimes more vaguely venter or alvus, both words for "belly". Vulva seems originally to have referred to the womb of animals, but is "extremely common" in Pliny's Natural History for a human uterus.[349] In the Imperial era, vulva can mean "female reproductive organs" collectively or vaguely, or sometimes refers to the vagina alone.[350] Early Latin Bible translators used vulva as the correct and proper word for the womb.[351] At some point during the Imperial era, matrix became the common word for "uterus", particularly in the gynecological writers of late antiquity, who also employ a specialized vocabulary for parts of the reproductive organs.[352]

Both women and men often removed their pubic hair,[353] but grooming may have varied over time and by individual preference. A fragment from the early satirist Lucilius refers to penetrating a "hairy bag",[354] and a graffito from Pompeii declares that "a hairy cunt is fucked much better than one which is smooth; it's steamy and wants cock".[355]

At the entrance to a caldarium in the bath complex of the House of Menander at Pompeii, an unusual graphic device appears on a mosaic: a phallic oil can is surrounded by strigils in the shape of female genitalia, juxtaposed with an "Ethiopian" water-bearer who has an "unusually large and comically detailed" penis.[356]

Breastsedit

Latin words for "breasts" include mammae (cf. English "mammary"), papillae (more specifically for "nipples"), and ubera, breasts in their capacity to provide nourishment, including the teats or udder of an animal.[n 10] Papillae is the preferred word when Catullus and the Augustan poets take note of breasts in an erotic context.[357]

The breasts of a beautiful woman were supposed to be "unobtrusive." Idealized breasts in the tradition of Hellenistic poetry were compared to apples;[358][359] Martial makes fun of large breasts.[360][361][362] Old women who were stereotypically ugly and undesirable in every way had "pendulous" breasts.[363] On the Roman stage, exaggerated breasts were part of the costuming for comically unattractive female characters, since in classic Roman comedy women's roles were played by male actors in drag.[364]

While Greek epigrams describe ideal breasts,[365] Latin poets take limited interest in them, at least as compared to the modern focus on admiring and fondling a woman's breasts.[366] They are observed mainly as aspects of a woman's beauty or perfection of form, though Ovid finds them inviting to touch.[367] In one poem celebrating a wedding, Catullus remarks on the bride's "tender nipples" (teneris ... papillis), which would keep a good husband sleeping with her; erotic appeal supports fidelity within marriage and leads to children and a long life together.[368]

Because all infants were breastfed in antiquity, the breast was viewed primarily as an emblem of nurturing and of motherhood.[369] Mastoi, breast-shaped drinking cups, and representations of breasts are among the votive offerings (vota) found at sanctuaries of deities such as Diana and Hercules, sometimes having been dedicated by wet nurses.[370][371] The breast-shaped cup may have a religious significance; the drinking of breast milk by an adult who is elderly or about to die symbolized potential rebirth in the afterlife.[372][373][374] In the Etruscan tradition, the goddess Juno (Uni) offers her breast to Hercules as a sign that he may enter the ranks of the immortals.[375][376] The religious meaning may underlie the story of how Pero offered breast milk to her elderly father when he was imprisoned and sentenced to death by starvation (see Roman Charity).[377] The scene is among the moral paintings in a Pompeiian bedroom that belonged to a child, along with the legend "in sadness is the meeting of modesty and piety".[378] Pliny records medicinal uses of breast milk, and ranks it as one of the most useful remedies, especially for ailments of the eyes and ears. Wrapping one's head in a bra was said to cure a headache.[379][380]

Baring the breasts is one of the gestures made by women, particularly mothers or nurses, to express mourning or as an appeal for mercy.[381] The baring and beating of breasts ritually in grief was interpreted by Servius as producing milk to feed the dead.[382] In Greek and Latin literature, mythological mothers sometimes expose their breasts in moments of extreme emotional duress to demand that their nurturing role be respected.[383] Breasts exposed with such intensity held apotropaic power.[384][160] Julius Caesar indicates that the gesture had a similar significance in Celtic culture: during the siege of Avaricum, the female heads of household (matres familiae) expose their breasts and extend their hands to ask that the women and children be spared.[385] Tacitus notes Germanic women who exhorted their reluctant men to valorous battle by aggressively baring their breasts.[386] Although in general "the gesture is meant to arouse pity rather than sexual desire", the beauty of the breasts so exposed is sometimes in evidence and remarked upon.[387]

Because women were normally portrayed clothed in art, bared breasts can signify vulnerability or erotic availability by choice, accident, or force. Baring a single breast was a visual motif of Classical Greek sculpture, where among other situations, including seductions,[388] it often represented impending physical violence or rape.[389] Some scholars have attempted to find a "code" in which exposing the right breast had an erotic significance, while the left breast signified nurturing.[390] Although art produced by the Romans may imitate or directly draw on Greek conventions, during the Classical period of Greek art images of women nursing were treated as animalistic or barbaric; by contrast, the coexisting Italic tradition emphasized the breast as a focus of the mother–child relationship and as a source of female power.[391]

The erogenous power of the breast was not utterly neglected: in comparing sex with a woman to sex with a boy, a Greek novel of the Roman Imperial era notes that "her breast when it is caressed provides its own particular pleasure".[392] Propertius connects breast development with girls reaching an age to "play".[393][394] Tibullus observes that a woman just might wear loose clothing so that her breasts "flash" when she reclines at dinner.[395] An astrological tradition held that mammary intercourse was enjoyed by men born under the conjunction of Venus, Mercury, and Saturn.[396] Even in the most sexually explicit Roman paintings, the breasts are sometimes covered by the strophium (breast band).[397][375] The women so depicted may be prostitutes, but it can be difficult to discern why an artist decides in a given scenario to portray the breasts covered or exposed.[398]

Female–female sexedit