A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

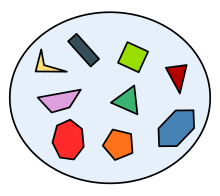

In mathematics, a set is a collection of different[1] things;[2][3][4] these things are called elements or members of the set and are typically mathematical objects of any kind: numbers, symbols, points in space, lines, other geometrical shapes, variables, or even other sets.[5] A set may have a finite number of elements or be an infinite set. There is a unique set with no elements, called the empty set; a set with a single element is a singleton.

Sets are uniquely characterized by their elements; this means that two sets that have precisely the same elements are equal (they are the same set).[6] This property is called extensionality. In particular, this implies that there is only one empty set.

Sets are ubiquitous in modern mathematics. Indeed, set theory, more specifically Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory, has been the standard way to provide rigorous foundations for all branches of mathematics since the first half of the 20th century.[5]

Definition and notation

Mathematical texts commonly denote sets by capital letters[7][5] in italic, such as A, B, C.[8] A set may also be called a collection or family, especially when its elements are themselves sets.

Roster notation

Roster or enumeration notation defines a set by listing its elements between curly brackets, separated by commas:[9][10][11][12]

This notation was introduced by Ernst Zermelo in 1908.[13] In a set, all that matters is whether each element is in it or not, so the ordering of the elements in roster notation is irrelevant (in contrast, in a sequence, a tuple, or a permutation of a set, the ordering of the terms matters). For example, {2, 4, 6} and {4, 6, 4, 2} represent the same set.[14][8][15]

For sets with many elements, especially those following an implicit pattern, the list of members can be abbreviated using an ellipsis '...'.[16][17] For instance, the set of the first thousand positive integers may be specified in roster notation as

Infinite sets in roster notation

An infinite set is a set with an endless list of elements. To describe an infinite set in roster notation, an ellipsis is placed at the end of the list, or at both ends, to indicate that the list continues forever. For example, the set of nonnegative integers is

and the set of all integers is

Semantic definition

Another way to define a set is to use a rule to determine what the elements are:

Such a definition is called a semantic description.[18][19]

Set-builder notation

Set-builder notation specifies a set as a selection from a larger set, determined by a condition on the elements.[19][20][21] For example, a set F can be defined as follows:

In this notation, the vertical bar "|" means "such that", and the description can be interpreted as "F is the set of all numbers n such that n is an integer in the range from 0 to 19 inclusive". Some authors use a colon ":" instead of the vertical bar.[22]

Classifying methods of definition

Philosophy uses specific terms to classify types of definitions:

- An intensional definition uses a rule to determine membership. Semantic definitions and definitions using set-builder notation are examples.

- An extensional definition describes a set by listing all its elements.[19] Such definitions are also called enumerative.

- An ostensive definition is one that describes a set by giving examples of elements; a roster involving an ellipsis would be an example.

Membership

If B is a set and x is an element of B, this is written in shorthand as x ∈ B, which can also be read as "x belongs to B", or "x is in B".[23] The statement "y is not an element of B" is written as y ∉ B, which can also be read as "y is not in B".[24][25]

For example, with respect to the sets A = {1, 2, 3, 4}, B = {blue, white, red}, and F = {n | n is an integer, and 0 ≤ n ≤ 19},

The empty set

The empty set (or null set) is the unique set that has no members. It is denoted ∅, , { },[26][27] ϕ,[28] or ϕ.[29]

Singleton sets

A singleton set is a set with exactly one element; such a set may also be called a unit set.[6] Any such set can be written as {x}, where x is the element. The set {x} and the element x mean different things; Halmos[30] draws the analogy that a box containing a hat is not the same as the hat.

Subsets

If every element of set A is also in B, then A is described as being a subset of B, or contained in B, written A ⊆ B,[31] or B ⊇ A.[32] The latter notation may be read B contains A, B includes A, or B is a superset of A. The relationship between sets established by ⊆ is called inclusion or containment. Two sets are equal if they contain each other: A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A is equivalent to A = B.[20]

If A is a subset of B, but A is not equal to B, then A is called a proper subset of B. This can be written A ⊊ B. Likewise, B ⊋ A means B is a proper superset of A, i.e. B contains A, and is not equal to A.

A third pair of operators ⊂ and ⊃ are used differently by different authors: some authors use A ⊂ B and B ⊃ A to mean A is any subset of B (and not necessarily a proper subset),[33][24] while others reserve A ⊂ B and B ⊃ A for cases where A is a proper subset of B.[31]

Examples:

- The set of all humans is a proper subset of the set of all mammals.

- {1, 3} ⊂ {1, 2, 3, 4}.

- {1, 2, 3, 4} ⊆ {1, 2, 3, 4}.

The empty set is a subset of every set,[26] and every set is a subset of itself:[33]

- ∅ ⊆ A.

- A ⊆ A.

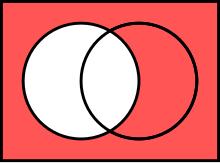

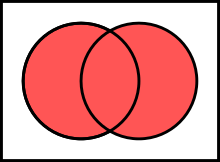

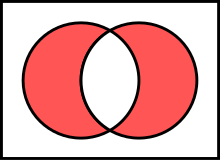

Euler and Venn diagrams

B is a superset of A.

An Euler diagram is a graphical representation of a collection of sets; each set is depicted as a planar region enclosed by a loop, with its elements inside. If A is a subset of B, then the region representing A is completely inside the region representing B. If two sets have no elements in common, the regions do not overlap.

A Venn diagram, in contrast, is a graphical representation of n sets in which the n loops divide the plane into 2n zones such that for each way of selecting some of the n sets (possibly all or none), there is a zone for the elements that belong to all the selected sets and none of the others. For example, if the sets are A, B, and C, there should be a zone for the elements that are inside A and C and outside B (even if such elements do not exist).

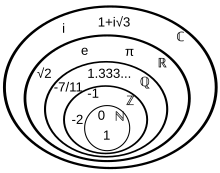

Special sets of numbers in mathematics

There are sets of such mathematical importance, to which mathematicians refer so frequently, that they have acquired special names and notational conventions to identify them.

Many of these important sets are represented in mathematical texts using bold (e.g. ) or blackboard bold (e.g. ) typeface.[34] These include

- or , the set of all natural numbers: (often, authors exclude 0);[34]

- or , the set of all integers (whether positive, negative or zero): ;[34]

- or , the set of all rational numbers (that is, the set of all proper and improper fractions): . For example, −7/4 ∈ Q and 5 = 5/1 ∈ Q;[34]

- or , the set of all real numbers, including all rational numbers and all irrational numbers (which include algebraic numbers such as that cannot be rewritten as fractions, as well as transcendental numbers such as π and e);[34]

- or , the set of all complex numbers: C = {a + bi | a, b ∈ R}, for example, 1 + 2i ∈ C.[34]

Each of the above sets of numbers has an infinite number of elements. Each is a subset of the sets listed below it.

Sets of positive or negative numbers are sometimes denoted by superscript plus and minus signs, respectively. For example, represents the set of positive rational numbers.

Functions

A function (or mapping) from a set A to a set B is a rule that assigns to each "input" element of A an "output" that is an element of B; more formally, a function is a special kind of relation, one that relates each element of A to exactly one element of B. A function is called

- injective (or one-to-one) if it maps any two different elements of A to different elements of B,

- surjective (or onto) if for every element of B, there is at least one element of A that maps to it, and

- bijective (or a one-to-one correspondence) if the function is both injective and surjective — in this case, each element of A is paired with a unique element of B, and each element of B is paired with a unique element of A, so that there are no unpaired elements.

An injective function is called an injection, a surjective function is called a surjection, and a bijective function is called a bijection or one-to-one correspondence.

Cardinality

The cardinality of a set S, denoted |S|, is the number of members of S.[35] For example, if B = {blue, white, red}, then |B| = 3. Repeated members in roster notation are not counted,[36][37] so |{blue, white, red, blue, white}| = 3, too.

More formally, two sets share the same cardinality if there exists a bijection between them.

The cardinality of the empty set is zero.[38]

Infinite sets and infinite cardinalityedit

The list of elements of some sets is endless, or infinite. For example, the set of natural numbers is infinite.[20] In fact, all the special sets of numbers mentioned in the section above are infinite. Infinite sets have infinite cardinality.

Some infinite cardinalities are greater than others. Arguably one of the most significant results from set theory is that the set of real numbers has greater cardinality than the set of natural numbers.[39] Sets with cardinality less than or equal to that of are called countable sets; these are either finite sets or countably infinite sets (sets of the same cardinality as ); some authors use "countable" to mean "countably infinite". Sets with cardinality strictly greater than that of are called uncountable sets.

However, it can be shown that the cardinality of a straight line (i.e., the number of points on a line) is the same as the cardinality of any segment of that line, of the entire plane, and indeed of any finite-dimensional Euclidean space.[40]

The continuum hypothesisedit

The continuum hypothesis, formulated by Georg Cantor in 1878, is the statement that there is no set with cardinality strictly between the cardinality of the natural numbers and the cardinality of a straight line.[41] In 1963, Paul Cohen proved that the continuum hypothesis is independent of the axiom system ZFC consisting of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice.[42] (ZFC is the most widely-studied version of axiomatic set theory.)

Power setsedit

The power set of a set S is the set of all subsets of S.[20] The empty set and S itself are elements of the power set of S, because these are both subsets of S. For example, the power set of {1, 2, 3} is {∅, {1}, {2}, {3}, {1, 2}, {1, 3}, {2, 3}, {1, 2, 3}}. The power set of a set S is commonly written as P(S) or 2S.[20][43][8]

If S has n elements, then P(S) has 2n elements.[44] For example, {1, 2, 3} has three elements, and its power set has 23 = 8 elements, as shown above.

If S is infinite (whether countable or uncountable), then P(S) is uncountable. Moreover, the power set is always strictly "bigger" than the original set, in the sense that any attempt to pair up the elements of S with the elements of P(S) will leave some elements of P(S) unpaired. (There is never a bijection from S onto P(S).)[45]

Partitionsedit

A partition of a set S is a set of nonempty subsets of S, such that every element x in S is in exactly one of these subsets. That is, the subsets are pairwise disjoint (meaning any two sets of the partition contain no element in common), and the union of all the subsets of the partition is S.[46][47]

Basic operationsedit

Suppose that a universal set U (a set containing all elements being discussed) has been fixed, and that A is a subset of U.

- The complement of A is the set of all elements (of U) that do not belong to A. It may be denoted Ac or A′. In set-builder notation, . The complement may also be called the absolute complement to distinguish it from the relative complement below. Example: If the universal set is taken to be the set of integers, then the complement of the set of even integers is the set of odd integers.

Given any two sets A and B,

- their union A ∪ B is the set of all things that are members of A or B or both.

- their intersection A ∩ B is the set of all things that are members of both A and B. If A ∩ B = ∅, then A and B are said to be disjoint.

- the set difference A \ B (also written A − B) is the set of all things that belong to A but not B. Especially when B is a subset of A, it is also called the relative complement of B in A. With Bc as the absolute complement of B (in the universal set U), A \ B = A ∩ Bc .

- their symmetric difference A Δ B is the set of all things that belong to A or B but not both. One has .

- their cartesian product A × B is the set of all ordered pairs (a,b) such that a is an element of A and b is an element of B.

Examples:

- {1, 2, 3} ∪ {3, 4, 5} = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}.

- {1, 2, 3} ∩ {3, 4, 5} = {3}.

- {1, 2, 3} − {3, 4, 5} = {1, 2}.

- {1, 2, 3} Δ {3, 4, 5} = {1, 2, 4, 5}.

- {a, b} × {1, 2, 3} = {(a,1), (a,2), (a,3), (b,1), (b,2), (b,3)}.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk