A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2022) |

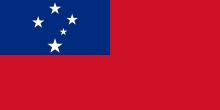

| Samoan | |

|---|---|

| Gagana faʻa Sāmoa | |

Map showing Samoa's central place in the Pacific, where the language is most spoken. | |

| Native to | Samoan Islands |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

| Ethnicity | Samoans |

Native speakers | 510,000 (2015)[1] |

Austronesian

| |

| Latin (Samoan alphabet) Samoan Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | sm |

| ISO 639-2 | smo |

| ISO 639-3 | smo |

| Glottolog | samo1305 |

| Linguasphere | 39-CAO-a |

| IETF | sm-WS (Samoa) |

Samoan (Gagana faʻa Sāmoa or Gagana Sāmoa; IPA: [ŋaˈŋana ˈsaːmʊa]) is a Polynesian language spoken by Samoans of the Samoan Islands. Administratively, the islands are split between the sovereign country of Samoa and the United States territory of American Samoa. It is an official language, alongside English, in both jurisdictions. It is widely spoken across the Pacific region, heavily so in New Zealand and also in Australia and the United States. Among the Polynesian languages, Samoan is the most widely spoken by number of native speakers.

Samoan is spoken by approximately 260,000 people in the archipelago and with many Samoans living in diaspora in a number of countries, the total number of speakers worldwide was estimated at 510,000 in 2015. It is the third-most widely spoken language in New Zealand, where 2.2% of the population, 101,900 people, were able to speak it as of 2018.[2]

The language is notable for the phonological differences between formal and informal speech as well as a ceremonial form used in Samoan oratory.

Classification

Samoan is an analytic, isolating language and a member of the Austronesian family, and more specifically the Samoic branch of the Polynesian subphylum. It is closely related to other Polynesian languages with many shared cognate words such as aliʻi, ʻava, atua, tapu and numerals as well as in the name of gods in mythology.

Linguists differ somewhat on the way they classify Samoan in relation to the other Polynesian languages.[3] The "traditional" classification,[4] based on shared innovations in grammar and vocabulary, places Samoan with Tokelauan, the Polynesian outlier languages and the languages of Eastern Polynesia, which include Rapanui, Māori, Tahitian and Hawaiian. Nuclear Polynesian and Tongic (the languages of Tonga and Niue) are the major subdivisions of Polynesian under this analysis. A revision by Marck reinterpreted the relationships among Samoan and the outlier languages. In 2008 an analysis, of basic vocabulary only, from the Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database is contradictory in that while in part it suggests that Tongan and Samoan form a subgroup,[5] the old subgroups Tongic and Nuclear Polynesian are still included in the classification search of the database itself.[6]

Geographic distribution

There are approximately 470,000 Samoan speakers worldwide, 50 percent of whom live in the Samoan Islands.[7]

Thereafter, the greatest concentration is in New Zealand, where there were 101,937 Samoan speakers at the 2018 census, or 2.2% of the country's population. Samoan is the third-most spoken language in New Zealand after English and Māori.[8]

According to the 2021 census in Australia conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the Samoan language is spoken in the homes of 49,021 people.[9]

US Census 2010 shows more than 180,000 Samoans reside in the United States, which is triple the number of people living in American Samoa, while slightly less than the estimated population of the island nation of Samoa – 193,000, as of July 2011.

Samoan Language Week (Vaiaso o le Gagana Sāmoa) is an annual celebration of the language in New Zealand supported by the government[10] and various organisations including UNESCO. Samoan Language Week was started in Australia for the first time in 2010.[11]

Phonology

The Samoan alphabet consists of 14 letters, with three more letters (H, K, R) used in loan words. The ʻ (koma liliu or ʻokina) is used for the glottal stop.

| Aa, Āā | Ee, Ēē | Ii, Īī | Oo, Ōō | Uu, Ūū | Ff | Gg | Ll | Mm | Nn | Pp | Ss | Tt | Vv | (Hh) | (Kk) | (Rr) | ‘ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /a/, /aː/ | /ɛ/, /eː/ | /ɪ/, /iː/ | /o/, /ɔː/ | /ʊ, w/, /uː/ | /f/ | /ŋ/ | /l~ɾ/ | /m/ | /n, ŋ/ | /p/ | /s/ | /t, k/ | /v/ | (/h/) | (/k/) | (/ɾ/) | /ʔ/ |

Vowels

Vowel length is phonemic in Samoan; all five vowels also have a long form denoted by the macron.[12] For example, tama means child or boy, while tamā means father.

Monophthongs

| Short | Long | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | Front | Back | |

| Close | i | u | iː | uː |

| Mid | e | o | eː | oː |

| Open | a | aː | ||

Diphthongs are /au ao ai ae ei ou ue/.

The combination of u followed by a vowel in some words creates the sound of the English w, a letter not part of the Samoan alphabet, as in uaua (artery, tendon).

/a/ is reduced to [ə] in only a few words, such as mate or maliu 'dead', vave 'be quick'.

Consonants

In formal Samoan, used for example in news broadcasts or sermons, the consonants /t n ŋ/ are used. In colloquial Samoan, however, /n ŋ/ merge as and /t/ is pronounced .[13]

The glottal stop /ʔ/ is phonemic in Samoan. Its presence or absence affects the meaning of words otherwise spelled the same,[12] e.g. mai = from, originate from; maʻi = sickness, illness. The glottal stop is represented by the koma liliu ("inverted comma"), which is recognized by Samoan scholars and the wider community.[12] The koma liliu is often replaced by an apostrophe in modern publications. Use of the apostrophe and macron diacritics in Samoan words was readopted by the Ministry of Education in 2012 after having been abandoned in the 1960s.[14]

/l/ is pronounced as a flap [ɾ] following a back vowel (/a, o, u/) and preceding an /i/; otherwise it is [l]. /s/ is less sibilant (hissing) than in English. /ɾ h/ are found in loan words.

| Labial | Alveolar | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |

| Plosive | p | t | (k) | ʔ |

| Fricative | f v | s | (h) | |

| Lateral | l | |||

| Rhotic | (r) |

The consonants in parentheses are only present in loanwords and formal Samoan.[15][16]

Foreign words

Loanwords from English and other languages have been adapted to Samoan phonology:[17]

- /k/ is retained in some instances (Christ = "Keriso", club = "kalapu", coffee = "kofe"), and has become in rare instances (such as "se totini", from the English "stocking").

- /ɹ/ becomes in some instances (e.g. Christ = "Keriso", January = "Ianuari", number = "numera"), and in others (January = "Ianuali", herring = "elegi").

- /d/ becomes (David = "Tavita", diamond = "taimane").

- /g/ becomes in some cases (gas = "kesi"), while /tʃ/, /ʃ/ and /dʒ/ usually become (Charles = "Salesi", Charlotte = "Salata", James = "Semisi").

- /h/ is retained at the beginning of some proper names (Herod = "Herota"), but in some cases becomes an 's' (hammer = "samala"), and is omitted in others (herring = "elegi", half-caste = "afakasi")

- /z/ becomes (Zachariah = "Sakaria")

- ?pojem= becomes (William = "Viliamu")

- /b/ becomes (Britain = "Peretania", butter = "pata")

Stress

Stress generally falls on the penultimate mora; that is, on the last syllable if that contains a long vowel or diphthong or on the second-last syllable otherwise.

Verbs formed from nouns ending in a, and meaning to abound in, have properly two aʻs, as puaa (puaʻaa), pona, tagata, but are written with one.

In speaking of a place at some distance, the accent is placed on the last syllable; as ʻO loʻo i Safotu, he is at Safotu. The same thing is done in referring to a family; as Sa Muliaga, the family of Muliaga, the term Sa referring to a wide extended family of clan with a common ancestor. So most words ending in ga, not a sign of a noun, as tigā, puapuaga, pologa, faʻataga and aga. So also all words ending in a diphthong, as mamau, mafai, avai.[17]

In speaking the voice is raised, and the emphasis falls on the last word in each sentence.

When a word receives an addition by means of an affixed particle, the accent is shifted forward; as alofa, love; alofága, loving, or showing love; alofagía, beloved.

Reduplicated words have two accents; as palapala, mud; segisegi, twilight. Compound words may have even three or four, according to the number of words and affixes of which the compound word is composed; as tofátumoánaíná, to be engulfed.

The articles le and se are unaccented. When used to form a pronoun or participle, le and se are contractions for le e, se e, and so are accented; as ʻO le ona le meae, the owner, literally the (person) whose (is) the thing, instead of O le e ona le meae. The sign of the nominative ʻoe, the prepositions o, a, i, e, and the euphonic particles i and te, are unaccented; as ʻO maua, ma te o atu ia te oee, we two will go to you.

Ina, the sign of the imperative, is accented on the ultima; ína, the sign of the subjunctive, on the penultima. The preposition iá is accented on the ultima, the pronoun ia on the penultima.[17]

Phonotactics

Samoan syllable structure is (C)V, where V may be long or a diphthong. A sequence VV may occur only in derived forms and compound words; within roots, only the initial syllable may be of the form V. Metathesis of consonants is frequent, such as manu for namu 'scent', lavaʻau for valaʻau 'to call', but vowels may not be mixed up in this way.

Every syllable ends in a vowel. No syllable consists of more than three sounds, one consonant and two vowels, the two vowels making a diphthong; as fai, mai, tau. Roots are sometimes monosyllabic, but mostly disyllabic or a word consisting of two syllables. Polysyllabic words are nearly all derived or compound words; as nofogatā from nofo (sit, seat) and gatā, difficult of access; taʻigaafi, from taʻi, to attend, and afi, fire, the hearth, making to attend to the fire; talafaʻasolopito, ("history") stories placed in order, faletalimalo, ("communal house") house for receiving guests.[17]

Grammar

Morphology

Personal pronouns

Like many Austronesian languages, Samoan has separate words for inclusive and exclusive we, and distinguishes singular, dual, and plural. The root for the inclusive pronoun may occur in the singular, in which case it indicates emotional involvement on the part of the speaker.

| singular | dual | plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | exclusive | a‘u, ‘ou | mā‘ua, mā | mātou |

| inclusive | tā‘ua, tā | tātou | ||

| 2nd person | ‘oe, ‘e | ‘oulua | ‘outou, tou | |

| 3rd person | ia / na | lā‘ua | lātou | |

In formal speech, fuller forms of the roots mā-, tā-, and lā- are ‘imā-, ‘itā-, and ‘ilā-.

Articles

Articles in Samoan do not show the definiteness of the noun phrase as do those of English but rather specificity.[18]

| singular | plural | |

|---|---|---|

| specific | le | ∅ |

| non-specific | se | ni |

The singular specific article le has frequently, erroneously, been referred to as a "definite" article, such as by Pratt, often with an additional vague explanation that it is sometimes used where English would require the indefinite article.[17] As a specific, rather than a definite article, it is used for specific referents that the speaker has in mind (specificity), regardless of whether the listener is expected to know which specific referent(s) is/are intended (definiteness). A sentence such as ʻUa tu mai le vaʻa, could thus, depending on context, be translated into English as "A canoe appears", when the listener or reader is not expected to know which canoe, or "The canoe appears", if the listener or reader is expected to know which canoe, such as when the canoe has previously been mentioned.

The plural specific is marked by a null article: ʻO le tagata "the person", ʻO tagata "people". (The word ʻoe in these examples is not an article but a "presentative" preposition. It marks noun phrases used as clauses, introducing clauses or used as appositions etc.)

The non-specific singular article se is used when the speaker doesn't have a particular individual of a class in mind, such as in the sentence Ta mai se laʻau, "Cut me a stick", whereby there is no specific stick intended. The plural non-specific article ni is the plural form and may be translated into English as "some" or "any", as in Ta mai ni laʻau, "Cut me some sticks".[18][17]

In addition, Samoan possesses a series of diminutive articles.

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Specific diminutive-emotional | si | / |

| (Non-)specific diminutive-partitive | sina | / |

| Specific diminutive | / | nāi / nai |

| Non-specific diminutive | / | ni nāi / ni nai |

Nounsedit

Names of natural objects, such as men, trees and animals, are mostly primitive nouns, e.g. ʻO le la, the sun; ʻo le tagata, the person; ʻo le talo, the taro; ʻo le iʻa, the fish; also manufactured articles, such as matau, an axe, vaʻa, canoe, tao, spear, fale, house, etc.[17]

Some nouns are derived from verbs by the addition of either ga, saga, taga, maga, or ʻaga: such as tuli, to chase; tuliga, chasing; luluʻu, to fill the hand; luʻutaga, a handful; feanu, to spit; anusaga, spittle; tanu, to bury; tanulia, the part buried. These verbal nouns have an active participial meaning; e.g. ʻO le faiga o le fale, the building of the house. Often they refer to the persons acting, in which case they govern the next noun in the genitive with a; ʻO le faiga a fale, contracted into ʻo le faiga fale, those who build the house, the builders. In some cases verbal nouns refer to either persons or things done by them: ʻO le faiga a talo, the getting of taro, or the party getting the taro, or the taro itself which has been got. The context in such cases decides the meaning. Sometimes place is indicated by the termination; such as tofā, to sleep; tofāga, a sleeping-place, a bed. ʻO le taʻelega is either the bathing-place or the party of bathers. The first would take o after it to govern the next noun, ʻO le taʻelega o le nuʻu, the bathing-place of the village; the latter would be followed by a, ʻO le taʻelega a teine, the bathing-place of the girls.

Sometimes such nouns have a passive meaning, such as being acted upon; ʻO le taomaga a lau, the thatch that has been pressed; ʻo le faupuʻega a maʻa, the heap of stones, that is, the stones which have been heaped up. Those nouns which take ʻaga are rare, except on Tutuila; gataʻaga, the end; ʻamataʻaga, the beginning; olaʻaga, lifetime; misaʻaga, quarrelling. Sometimes the addition of ga makes the signification intensive; such as ua and timu, rain; uaga and timuga, continued pouring (of rain).

The simple form of the verb is sometimes used as a noun: tatalo, to pray; ʻo le tatalo, a prayer; poto, to be wise; ʻo le poto, wisdom.

The reciprocal form of the verb is often used as a noun; e.g. ʻO le fealofani, ʻo femisaiga, quarrellings (from misa), feʻumaiga; E lelei le fealofani, mutual love is good.

A few diminutives are made by reduplication, e.g. paʻapaʻa, small crabs; pulepule, small shells; liilii, ripples; 'ili'ili, small stones.

Adjectives are made into abstract nouns by adding an article or pronoun; e.g. lelei, good; ʻo le lelei, goodness; silisili, excellent or best; ʻo lona lea silisili, that is his excellence or that is his best.

Many verbs may become participle-nouns by adding ga; as sau, come, sauga; e.g. ʻO lona sauga muamua, his first coming; mau" to mauga, ʻO le mauga muamua, the first dwelling.

Genderedit

As there is no proper gender in Oceanic languages, different genders are sometimes expressed by distinct names:

| Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ʻO le matai | a chief | ʻO le tamaitaʻi | a lady |

| ʻO le tamāloa | a man | ʻO le fafine | a woman |

| ʻO le tama | a boy | ʻO le teine | a girl |

| ʻO le poʻa | a male animal | ʻO le manu fafine | a female animal |

| ʻO le toeaʻina | an elderly man | ʻO le loʻomatua | an elderly woman |

| sole | colloquial male label | suga, funa | colloquial female label |

When no distinct name exists, the gender of animals is known by adding poʻa and fafine respectively. The gender of some few plants is distinguished by tane and fafine, as in ʻo le esi tane; ʻo le esi fafine. No other names of objects have any mark of gender.[17]

Numberedit

The singular number is known by the article with the noun; e.g. ʻo le tama, a boy.

Properly there is no dual. It is expressed by omitting the article and adding numbers e lua for things e.g. e toʻalua teine, two girls, for persons; or ʻo fale e lua, two houses; ʻo tagata e toʻalua, two persons; or ʻo lāʻua, them/those two (people).

The plural is known by:

- the omission of the article; ʻo ʻulu, breadfruits.

- particles denoting multitude, as ʻau, vao, mou, and moíu, and such plural is emphatic; ʻo le ʻau iʻa, a shoal of fishes; ʻo le vao tagata, a forest of men, i.e., a great company; ʻo le mou mea, a great number of things; ʻo le motu o tagata, a crowd of people. These particles cannot be used indiscriminately; motu could not be used with fish, nor ʻau with men.

- lengthening, or more correctly doubling, a vowel in the word; tuafāfine, instead of tuafafine, sisters of a brother. This method is rare.[17]

Plurality is also expressed by internal reduplication in Samoan verbs (-CV- infix), by which the root or stem of a word, or part of it, is repeated.

savali

walk (SG)

→

sāvavali

walking (PL)

(sā-va-vali)

alofa

love (SG)

→

ālolofa

loving (PL)

(a-lo-lofa) (Moravcsik 1978, Broselow and McCarthy 1984)

Possessivesedit

Possessive relations are indicated by the particles a or o. Possessive pronouns also have a-forms and o-forms: lou, lau, lona, lana, lo and la matou, etc. Writers in the 1800s like Platt were unable to understand the underlying principles governing the use of the two forms: "There is no general rule which will apply to every case. The governing noun decides which should be used; thus ʻO le poto ʻo le tufuga fai fale, "the wisdom of the builder"; ʻO le amio a le tama, "the conduct of the boy"; ʻupu o fāgogo, "words of fāgogo" (a form of narrated and sung storytelling); but ʻupu a tagata, "words of men". Pratt instead gives a rote list of uses and exceptions:

O is used with:

- Nouns denoting parts of the body; fofoga o le aliʻi, eyes of the chief. So of hands, legs, hair, etc.; except the beard, which takes a, lana ʻava; but a chief's is lona soesa. Different terms and words apply to chiefs and people of rank and status according to the 'polite' variant of the Samoan language, similar to the 'polite' variant in the Japanese language.

- The mind and its affections; ʻo le toʻasa o le aliʻi, the wrath of the chief. So of the will, desire, love, fear, etc.; ʻO le manaʻo o le nuʻu, the desire of the land; ʻO le mataʻu o le tama, the fear of the boy.

- Houses, and all their parts; canoes, land, country, trees, plantations; thus, pou o le fale, posts of the house; lona fanua, lona naʻu, etc.

- People, relations, slaves; ʻo ona tagata, his people; ʻo le faletua o le aliʻi, the chief's wife. So also of a son, daughter, father, etc. Exceptions; Tane, husband; ava, wife (of a common man), and children, which take a; lana, ava, ma, ana, fānau.

- Garments, etc., if for use; ona ʻofu. Except when spoken of as property, riches, things laid up in store.

A is used with:

- Words denoting conduct, custom, etc.; amio, masani, tu.

- Language, words, speeches; gagana, upu, fetalaiga, afioga; ʻO le upu a le tama.

- Property of every kind. Except garments, etc., for use.

- Those who serve, animals, men killed and carried off in war; lana tagata.

- Food of every kind.

- Weapons and implements, as clubs, knives, swords, bows, cups, tattooing instruments, etc. Except spears, axes, and ʻoso (the stick used for planting taro), which take o.

- Work; as lana galuega. Except faiva, which takes o.

Some words take either a or o; as manatu, taofi, ʻO se tali a Matautu, an answer given by Matautu; ʻo se tali ʻo Matautu, an answer given to Matautu.

Exceptions:

- Nouns denoting the vessel and its contents do not take the particle between them: ʻo le ʻato talo, a basket of taro; ʻo le fale oloa, a house of property, shop, or store-house.

- Nouns denoting the material of which a thing is made: ʻO le tupe auro, a coin of gold; ʻo le vaʻa ifi, a canoe of teak.

- Nouns indicating members of the body are rather compounded with other nouns instead of being followed by a possessive particle: ʻO le mataivi, an eye of bone; ʻo le isu vaʻa, a nose of a canoe; ʻo le gutu sumu, a mouth of the sumu (type of fish); ʻo le loto alofa, a heart of love.

- Many other nouns are compounded in the same way: ʻO le apaau tane, the male wing; ʻo le pito pou, the end of the post.

- The country or town of a person omits the particle: ʻO le tagata Sāmoa, a man or person of Samoa.

- Nouns ending in a, lengthen (or double) that letter before other nouns in the possessive form: ʻO le sua susu; ʻo le maga ala, or maga a ala, a branch road.

- The sign of the possessive is not used between a town and its proper name, but the topic marker ʻoe is repeated; thus putting the two in apposition: ʻO le ʻaʻai ʻo Matautu, the commons of Matautu.

Adjectivesedit

Some adjectives are primitive, as umi, long; poto, wise. Some are formed from nouns by the addition of a, meaning "covered with" or "infested with"; thus, ʻeleʻele, dirt; ʻeleʻelea, dirty; palapala, mud; palapalā, muddy.

Others are formed by doubling the noun; as pona, a knot; ponapona, knotty; fatu, a stone; fatufatu, stony.

Others are formed by prefixing faʻa to the noun; as ʻo le tu faʻasāmoa, Samoan custom or faʻamatai.

Like ly in English, the faʻa often expresses similitude; ʻo le amio faʻapuaʻa, behave like a pig (literally).

In one or two cases a is prefixed; as apulupulu, sticky, from pulu, resin; avanoa, open; from vā and noa.

Verbs are also used as adjectives: ʻo le ala faigatā, a difficult road; ʻo le vai tafe, a river, flowing water; ʻo le laʻau ola, a live tree; also the passive: ʻo le aliʻi mātaʻutia.

Ma is the prefix of condition, sae, to tear; masae, torn; as, ʻO le ʻie masae, torn cloth; Goto, to sink; magoto, sunk; ʻo le vaʻa magoto, a sunken canoe.

A kind of compound adjective is formed by the union of a noun with an adjective; as ʻo le tagata lima mālosi, a strong man, literally, the stronghanded man; ʻo le tagata loto vaivai, a weak-spirited man.

Nouns denoting the materials out of which things are made are used as adjectives: ʻo le mama auro, a gold ring; ʻo le fale maʻa, a stone house. Or they may be reckoned as nouns in the genitive.

Adjectives expressive of colours are mostly reduplicated words; as sinasina or paʻepaʻe (white); uliuli (black); samasama (yellow); ʻenaʻena (brown); mumu (red), etc.; but when they follow a noun they are usually found in their simple form; as ʻo le ʻie sina, white cloth; ʻo le puaʻa uli, a black pig. The plural is sometimes distinguished by doubling the first syllable; as sina, white; plural, sisina; tele, great; pl. tetele. In compound words the first syllable of the root is doubled; as maualuga, high; pl. maualuluga. Occasionally the reciprocal form is used as a plural; as lele, flying; ʻo manu felelei, flying creatures, birds.

Comparison is generally effected by using two adjectives, both in the positive state; thus e lelei lenei, ʻa e leaga lena, this is good – but that is bad, not in itself, but in comparison with the other; e umi lenei, a e puupuu lena, this is long, that is short.

The superlative is formed by the addition of an adverb, such as matuā, tasi, sili, silisiliʻese aʻiaʻi, naʻuā; as ʻua lelei tasi, it alone is good – that is, nothing equals it. ʻUa matuā silisili ona lelei, it is very exceedingly good; ʻua tele naʻuā, it is very great. Silisili ese, highest, ese, differing from all others.

Naua has often the meaning of "too much"; ua tele naua, it is greater than is required.

Syntaxedit

Sentences have different types of word order and the four most commonly used are:

- verb–subject–object (VSO)

- verb–object–subject (VOS)

- subject–verb–object (SVO)

- object–verb–subject (OVS)[12][19][20]

For example:- 'The girl went to the house.' (SVO); girl (subject), went (verb), house (object).

Samoan word order;

Sa alu

went

le teine

girl

ʻi le

fale.

house

Sa alu

went

ʻi le

fale

house

le teine.

girl

Le

fale

house

sa alu

went

ʻi ai

le teine.

girl

Le teine

girl

sa alu

went

ʻi le

fale.

house

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk