A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Runic ᚱᚢᚾᛁᚲ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | Alphabet

|

Time period | Elder Futhark from the 2nd century AD |

| Direction | Left-to-right, boustrophedon |

| Languages | Germanic languages |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Elder Futhark, Younger Futhark, Anglo-Saxon futhorc |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Runr (211), Runic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Runic |

| U+16A0–U+16FF[2] | |

| History of the alphabet | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

||

A rune is a letter in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised purposes thereafter. In addition to representing a sound value (a phoneme), runes can be used to represent the concepts after which they are named (ideographs). Scholars refer to instances of the latter as Begriffsrunen ('concept runes'). The Scandinavian variants are also known as fuþark, or futhark, these names derived from the first six letters of the script, ⟨ᚠ⟩, ⟨ᚢ⟩, ⟨ᚦ⟩, ⟨ᚨ⟩/⟨ᚬ⟩, ⟨ᚱ⟩, and ⟨ᚲ⟩/⟨ᚴ⟩, corresponding to the Latin letters ⟨f⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨þ⟩/⟨th⟩, ⟨a⟩, ⟨r⟩, and ⟨k⟩. The Anglo-Saxon variant is futhorc, or fuþorc, due to changes in Old English of the sounds represented by the fourth letter, ⟨ᚨ⟩/⟨ᚩ⟩.

Runology is the academic study of the runic alphabets, runic inscriptions, runestones, and their history. Runology forms a specialised branch of Germanic philology.

The earliest secure runic inscriptions date from around AD 150, with a potentially earlier inscription dating to AD 50 and Tacitus's potential description of rune use from around AD 98. The Svingerud Runestone dates from between AD 1 to 250. Runes were generally replaced by the Latin alphabet as the cultures that had used runes underwent Christianisation, by approximately AD 700 in central Europe and 1100 in northern Europe. However, the use of runes persisted for specialized purposes beyond this period. Up until the early 20th century, runes were still used in rural Sweden for decorative purposes in Dalarna and on runic calendars.

The three best-known runic alphabets are the Elder Futhark (c. AD 150–800), the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc (400–1100), and the Younger Futhark (800–1100). The Younger Futhark is divided further into the long-branch runes (also called Danish, although they were also used in Norway, Sweden, and Frisia); short-branch, or Rök, runes (also called Swedish–Norwegian, although they were also used in Denmark); and the stavlösa, or Hälsinge, runes (staveless runes). The Younger Futhark developed further into the medieval runes (1100–1500), and the Dalecarlian runes (c. 1500–1800).

The exact development of the early runic alphabet remains unclear but the script ultimately stems from the Phoenician alphabet. Early runes may have developed from the Raetic, Venetic, Etruscan, or Old Latin as candidates. At the time, all of these scripts had the same angular letter shapes suited for epigraphy, which would become characteristic of the runes and related scripts in the region.

The process of transmission of the script is unknown. The oldest clear inscriptions are found in Denmark and northern Germany. A "West Germanic hypothesis" suggests transmission via Elbe Germanic groups, while a "Gothic hypothesis" presumes transmission via East Germanic expansion. Runes continue to be used in a wide variety of ways in modern popular culture.

Name

Etymology

The name stems from a Proto-Germanic form reconstructed as *rūnō, which may be translated as 'secret, mystery; secret conversation; rune'. It is the source of Gothic rūna (𐍂𐌿𐌽𐌰, 'secret, mystery, counsel'), Old English rún ('whisper, mystery, secret, rune'), Old Saxon rūna ('secret counsel, confidential talk'), Middle Dutch rūne ('id'), Old High German rūna ('secret, mystery'), and Old Norse rún ('secret, mystery, rune').[5][6] The earliest Germanic epigraphic attestation is the Primitive Norse rūnō (accusative singular), found on the Einang stone (AD 350–400) and the Noleby stone (AD 450).[4]

The term is related to Proto-Celtic *rūna ('secret, magic'), which is attested in Old Irish rún ('mystery, secret'), Middle Welsh rin ('mystery, charm'), Middle Breton rin ('secret wisdom'), and possibly in the ancient Gaulish Cobrunus (< *com-rūnos 'confident'; cf. Middle Welsh cyfrin, Middle Breton queffrin, Middle Irish comrún 'shared secret, confidence') and Sacruna (< *sacro-runa 'sacred secret'), as well as in Lepontic Runatis (< *runo-ātis 'belonging to the secret'). However, it is difficult to tell whether they are cognates (linguistic siblings from a common origin), or if the Proto-Germanic form reflects an early borrowing from Celtic.[7][8] Various connections have been proposed with other Indo-European terms (for example: Sanskrit ráuti रौति 'roar', Latin rūmor 'noise, rumor'; Ancient Greek eréō ἐρέω 'ask' and ereunáō ἐρευνάω 'investigate'),[9] although linguist Ranko Matasović finds them difficult to justify for semantic or linguistic reasons.[7] Because of this, some scholars have speculated that the Germanic and Celtic words may have been a shared religious term borrowed from an unknown non-Indo-European language.[4][7]

Related terms

In early Germanic, a rune could also be referred to as *rūna-stabaz, a compound of *rūnō and *stabaz ('staff; letter'). It is attested in Old Norse rúna-stafr, Old English rún-stæf, and Old High German rūn-stab.[10] Other Germanic terms derived from *rūnō include *runōn ('counsellor'), *rūnjan and *ga-rūnjan ('secret, mystery'), *raunō ('trial, inquiry, experiment'), *hugi-rūnō ('secret of the mind, magical rune'), and *halja-rūnō ('witch, sorceress'; literally ' Hel-secret').[11] It is also often part of personal names, including Gothic Runilo (𐍂𐌿𐌽𐌹𐌻𐍉), Frankish Rúnfrid, Old Norse Alfrún, Dagrún, Guðrún, Sigrún, Ǫlrún, Old English Ælfrún, and Lombardic Goderūna.[9]

The Finnish word runo, meaning 'poem', is an early borrowing from Proto-Germanic,[12] and the source of the term for rune, riimukirjain, meaning 'scratched letter'.[13] The root may also be found in the Baltic languages, where Lithuanian runoti means both 'to cut (with a knife)' and 'to speak'.[14]

The Old English form rún survived into the early modern period as roun, which is now obsolete. The modern English rune is a later formation that is partly derived from Late Latin runa, Old Norse rún, and Danish rune.[6]

History and use

The runes were in use among the Germanic peoples from the 1st or 2nd century AD.[a] This period corresponds to the late Common Germanic stage linguistically, with a continuum of dialects not yet clearly separated into the three branches of later centuries: North Germanic, West Germanic, and East Germanic.

No distinction is made in surviving runic inscriptions between long and short vowels, although such a distinction was certainly present phonologically in the spoken languages of the time. Similarly, there are no signs for labiovelars in the Elder Futhark (such signs were introduced in both the Anglo-Saxon futhorc and the Gothic alphabet as variants of p; see peorð.)

Origins

The formation of the Elder Futhark was complete by the early 5th century, with the Kylver Stone being the first evidence of the futhark ordering as well as of the p rune.

Specifically, the Rhaetic alphabet of Bolzano is often advanced as a candidate for the origin of the runes, with only five Elder Futhark runes (ᛖ e, ᛇ ï, ᛃ j, ᛜ ŋ, ᛈ p) having no counterpart in the Bolzano alphabet.[16] Scandinavian scholars tend to favor derivation from the Latin alphabet itself over Rhaetic candidates.[17][18][19] A "North Etruscan" thesis is supported by the inscription on the Negau helmet dating to the 2nd century BC.[20] This is in a northern Etruscan alphabet but features a Germanic name, Harigast. Giuliano and Larissa Bonfante suggest that runes derived from some North Italic alphabet, specifically Venetic: But since Romans conquered Veneto after 200 BC, and then the Latin alphabet became prominent and Venetic culture diminished in importance, Germanic people could have adopted the Venetic alphabet within the 3rd century BC or even earlier.[21]

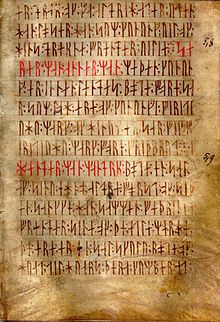

The angular shapes of the runes are shared with most contemporary alphabets of the period that were used for carving in wood or stone. There are no horizontal strokes: when carving a message on a flat staff or stick, it would be along the grain, thus both less legible and more likely to split the wood.[22] This characteristic is also shared by other alphabets, such as the early form of the Latin alphabet used for the Duenos inscription, but it is not universal, especially among early runic inscriptions, which frequently have variant rune shapes, including horizontal strokes. Runic manuscripts (that is written rather than carved runes, such as Codex Runicus) also show horizontal strokes.

The "West Germanic hypothesis" speculates on an introduction by West Germanic tribes. This hypothesis is based on claiming that the earliest inscriptions of the 2nd and 3rd centuries, found in bogs and graves around Jutland (the Vimose inscriptions), exhibit word endings that, being interpreted by Scandinavian scholars to be Proto-Norse, are considered unresolved and long having been the subject of discussion.[b] In the early Runic period, differences between Germanic languages are generally presumed to be small. Another theory presumes a Northwest Germanic unity preceding the emergence of Proto-Norse proper from roughly the 5th century.[c][d] An alternative suggestion explaining the impossibility of classifying the earliest inscriptions as either North or West Germanic is forwarded by È. A. Makaev, who presumes a "special runic koine", an early "literary Germanic" employed by the entire Late Common Germanic linguistic community after the separation of Gothic (2nd to 5th centuries), while the spoken dialects may already have been more diverse.[28]

The Meldorf fibula and Tacitus's Germania

With the potential exception of the Meldorf fibula, a possible runic inscription found in Schleswig-Holstein dating to around 50 AD, the earliest reference to runes (and runic divination) may occur in Roman Senator Tacitus's ethnographic Germania.[29] Dating from around 98 CE, Tacitus describes the Germanic peoples as utilizing a divination practice involving rune-like inscriptions:

For divination and casting lots they have the highest possible regard. Their procedure for casting lots is uniform: They break off the branch of a fruit tree and slice into strips; they mark these by certain signs and throw them, as random chance will have it, on to a white cloth. Then a state priest, if the consultation is a public one, or the father of the family, if it is private, prays to the gods and, gazing to the heavens, picks up three separate strips and reads their meaning from the marks scored on them. If the lots forbid an enterprise, there can be no further consultation about it that day; if they allow it, further confirmation by divination is required.[30]

As Victoria Symons summarizes, "If the inscriptions made on the lots that Tacitus refers to are understood to be letters, rather than other kinds of notations or symbols, then they would necessarily have been runes, since no other writing system was available to Germanic tribes at this time."[29]

Early inscriptions

Runic inscriptions from the 400-year period 150–550 AD are described as "Period I". These inscriptions are generally in Elder Futhark, but the set of letter shapes and bindrunes employed is far from standardized. Notably the j, s, and ŋ runes undergo considerable modifications, while others, such as p and ï, remain unattested altogether prior to the first full futhark row on the Kylver Stone (c. 400 AD).

Artifacts such as spear heads or shield mounts have been found that bear runic marking that may be dated to 200 AD, as evidenced by artifacts found across northern Europe in Schleswig (North Germany), Funen, Zealand, Jutland (Denmark), and Scania (Sweden). Earlier—but less reliable—artifacts have been found in Meldorf, Süderdithmarschen, in northern Germany; these include brooches and combs found in graves, most notably the Meldorf fibula, and are supposed to have the earliest markings resembling runic inscriptions.

Magical or divinatory use

The stanza 157 of Hávamál attribute to runes the power to bring that which is dead back to life. In this stanza, Odin recounts a spell:

Þat kann ek it tolfta, |

I know a twelfth one |

The earliest runic inscriptions found on artifacts give the name of either the craftsman or the proprietor, or sometimes, remain a linguistic mystery. Due to this, it is possible that the early runes were not used so much as a simple writing system, but rather as magical signs to be used for charms. Although some say the runes were used for divination, there is no direct evidence to suggest they were ever used in this way. The name rune itself, taken to mean "secret, something hidden", seems to indicate that knowledge of the runes was originally considered esoteric, or restricted to an elite.[citation needed] The 6th-century Björketorp Runestone warns in Proto-Norse using the word rune in both senses:

Haidzruno runu, falahak haidera, ginnarunaz. Arageu haeramalausz uti az. Weladaude, sa'z þat barutz. Uþarba spa.

I, master of the runes(?) conceal here runes of power. Incessantly (plagued by) maleficence, (doomed to) insidious death (is) he who breaks this (monument). I prophesy destruction / prophecy of destruction.[33]

The same curse and use of the word, rune, is also found on the Stentoften Runestone. There also are some inscriptions suggesting a medieval belief in the magical significance of runes, such as the Franks Casket (AD 700) panel.

Charm words, such as auja, laþu, laukaʀ, and most commonly, alu,[34] appear on a number of Migration period Elder Futhark inscriptions as well as variants and abbreviations of them. Much speculation and study has been produced on the potential meaning of these inscriptions. Rhyming groups appear on some early bracteates that also may be magical in purpose, such as salusalu and luwatuwa. Further, an inscription on the Gummarp Runestone (500–700 AD) gives a cryptic inscription describing the use of three runic letters followed by the Elder Futhark f-rune written three times in succession.[35]

Nevertheless, it has proven difficult to find unambiguous traces of runic "oracles": although Norse literature is full of references to runes, it nowhere contains specific instructions on divination. There are at least three sources on divination with rather vague descriptions that may, or may not, refer to runes: Tacitus's 1st-century Germania, Snorri Sturluson's 13th-century Ynglinga saga, and Rimbert's 9th-century Vita Ansgari.

The first source, Tacitus's Germania,[36] describes "signs" chosen in groups of three and cut from "a nut-bearing tree", although the runes do not seem to have been in use at the time of Tacitus' writings. A second source is the Ynglinga saga, where Granmar, the king of Södermanland, goes to Uppsala for the blót. There, the "chips" fell in a way that said that he would not live long (Féll honum þá svo spánn sem hann mundi eigi lengi lifa). These "chips", however, are easily explainable as a blótspánn (sacrificial chip), which was "marked, possibly with sacrificial blood, shaken, and thrown down like dice, and their positive or negative significance then decided."[37][page needed]

The third source is Rimbert's Vita Ansgari, where there are three accounts of what some believe to be the use of runes for divination, but Rimbert calls it "drawing lots". One of these accounts is the description of how a renegade Swedish king, Anund Uppsale, first brings a Danish fleet to Birka, but then changes his mind and asks the Danes to "draw lots". According to the story, this "drawing of lots" was quite informative, telling them that attacking Birka would bring bad luck and that they should attack a Slavic town instead. The tool in the "drawing of lots", however, is easily explainable as a hlautlein (lot-twig), which according to Foote and Wilson[38] would be used in the same manner as a blótspánn.

The lack of extensive knowledge on historical use of the runes has not stopped modern authors from extrapolating entire systems of divination from what few specifics exist, usually loosely based on the reconstructed names of the runes and additional outside influence.

A recent study of runic magic suggests that runes were used to create magical objects such as amulets,[39][page needed] but not in a way that would indicate that runic writing was any more inherently magical, than were other writing systems such as Latin or Greek.

Medieval use

As Proto-Germanic evolved into its later language groups, the words assigned to the runes and the sounds represented by the runes themselves began to diverge somewhat and each culture would create new runes, rename or rearrange its rune names slightly, or stop using obsolete runes completely, to accommodate these changes. Thus, the Anglo-Saxon futhorc has several runes peculiar to itself to represent diphthongs unique to (or at least prevalent in) Old English.

Some later runic finds are on monuments (runestones), which often contain solemn inscriptions about people who died or performed great deeds. For a long time it was presumed that this kind of grand inscription was the primary use of runes, and that their use was associated with a certain societal class of rune carvers.

In the mid-1950s, however, approximately 670 inscriptions, known as the Bryggen inscriptions, were found in Bergen.[40] These inscriptions were made on wood and bone, often in the shape of sticks of various sizes, and contained information of an everyday nature—ranging from name tags, prayers (often in Latin), personal messages, business letters, and expressions of affection, to bawdy phrases of a profane and sometimes even of a vulgar nature. Following this find, it is nowadays commonly presumed that, at least in late use, Runic was a widespread and common writing system.

In the later Middle Ages, runes also were used in the clog almanacs (sometimes called Runic staff, Prim, or Scandinavian calendar) of Sweden and Estonia. The authenticity of some monuments bearing Runic inscriptions found in Northern America is disputed; most of them have been dated to modern times.

Runes in Eddic poetry

In Norse mythology, the runic alphabet is attested to a divine origin (Old Norse: reginkunnr). This is attested as early as on the Noleby Runestone from c. 600 AD that reads Runo fahi raginakundo toja..., meaning "I prepare the suitable divine rune..."[41] and in an attestation from the 9th century on the Sparlösa Runestone, which reads Ok rað runaʀ þaʀ rægikundu, meaning "And interpret the runes of divine origin".[42] In the Poetic Edda poem Hávamál, Stanza 80, the runes also are described as reginkunnr:

Þat er þá reynt, |

That is now proved, |

The poem Hávamál explains that the originator of the runes was the major deity, Odin. Stanza 138 describes how Odin received the runes through self-sacrifice:

Veit ek at ek hekk vindga meiði a |

In stanza 139, Odin continues:

Við hleifi mik seldo ne viþ hornigi, |

No bread did they give me nor a drink from a horn, |

In the Poetic Edda poem Rígsþula another origin is related of how the runic alphabet became known to humans. The poem relates how Ríg, identified as Heimdall in the introduction, sired three sons—Thrall (slave), Churl (freeman), and Jarl (noble)—by human women. These sons became the ancestors of the three classes of humans indicated by their names. When Jarl reached an age when he began to handle weapons and show other signs of nobility, Ríg returned and, having claimed him as a son, taught him the runes. In 1555, the exiled Swedish archbishop Olaus Magnus recorded a tradition that a man named Kettil Runske had stolen three rune staffs from Odin and learned the runes and their magic.

Runic alphabets

Elder Futhark (2nd to 8th centuries)

The Elder Futhark, used for writing Proto-Norse, consists of 24 runes that often are arranged in three groups of eight; each group is referred to as an ætt (Old Norse, meaning 'clan, group'). The earliest known sequential listing of the full set of 24 runes dates to approximately AD 400 and is found on the Kylver Stone in Gotland, Sweden.

Most probably each rune had a name, chosen to represent the sound of the rune itself. The names are, however, not directly attested for the Elder Futhark themselves. Germanic philologists reconstruct names in Proto-Germanic based on the names given for the runes in the later alphabets attested in the rune poems and the linked names of the letters of the Gothic alphabet. For example, the letter /a/ was named from the runic letter ![]() called Ansuz. An asterisk before the rune names means that they are unattested reconstructions. The 24 Elder Futhark runes are the following:[45]

called Ansuz. An asterisk before the rune names means that they are unattested reconstructions. The 24 Elder Futhark runes are the following:[45]

| Rune | UCS | Trans. | IPA | Proto-Germanic name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᚠ | f | /ɸ/, /f/ | *fehu | "cattle; wealth" | |

| ᚢ | u | /u(ː)/ | ?*ūruz | "aurochs", Wild ox (or *ûram "water/slag"?) | |

| ᚦ | þ | /θ/, /ð/ | ?*þurisaz | "Thurs" (see Jötunn) or *þunraz ("the god Thunraz") | |

| ᚨ | a | /a(ː)/ | *ansuz | "god" | |

| ᚱ | r | /r/ | *raidō | "ride, journey" | |

| ᚲ | k (c) | /k/ | ?*kaunan | "ulcer"? (or *kenaz "torch"?) | |

| ᚷ | g | /ɡ/ | *gebō | "gift" | |

| ᚹ | w | ?pojem= | *wunjō | "joy" | |

| ᚺ ᚻ | h | /h/ | *hagalaz | "hail" (the precipitation) | |

| ᚾ | n | /n/ | *naudiz | "need" | |

| ᛁ | i | /i(ː)/ | *īsaz | "ice" | |

| ᛃ | j | /j/ | *jēra- | "year, good year, harvest" | |

| ᛇ | ï (æ) | /æː/[46] | *ī(h)waz | "yew-tree" | |

| ᛈ | p | /p/ | ?*perþ- | meaning unknown; possibly "pear-tree". | |

| ᛉ | z | /z/ | ?*algiz | "elk" (or "protection, defence"[47]) | |

| ᛊ ᛋ | s | /s/ | *sōwilō | "sun" | |

| ᛏ | t | /t/ | *tīwaz | "the god Tiwaz" | |

| ᛒ | b | /b/ | *berkanan | "birch" | |

| ᛖ

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Runes Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Analytika

Antropológia Aplikované vedy Bibliometria Dejiny vedy Encyklopédie Filozofia vedy Forenzné vedy Humanitné vedy Knižničná veda Kryogenika Kryptológia Kulturológia Literárna veda Medzidisciplinárne oblasti Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy Metavedy Metodika Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk |