A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, spans from the original peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, the era covers the history of Indigenous cultures until significant influence by Europeans. This may have occurred decades or even centuries after Columbus for certain cultures.

Many pre-Columbian civilizations were marked by permanent settlements, cities, agriculture, civic and monumental architecture, major earthworks, and complex societal hierarchies. Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first permanent European colonies (c. late 16th–early 17th centuries),[1] and are known only through archaeological investigations and oral history. Other civilizations were contemporary with the colonial period and were described in European historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Maya civilization, kept written records, but due to many Christian Europeans of the time viewing such texts as pagan, men like Diego de Landa burned them, even while seeking to preserve native histories. Only a few hidden documents have survived in their original languages, while others were transcribed or dictated into Spanish, giving modern historians glimpses of ancient culture and knowledge.

Historiography

Before the development of archaeology in the 19th century, historians of the pre-Columbian period mainly interpreted the records of the European conquerors and the accounts of early European travelers and antiquaries. It was not until the nineteenth century that the work of people such as John Lloyd Stephens, Eduard Seler, and Alfred Maudslay, and institutions such as the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Harvard University, led to the reconsideration and criticism of the early European sources. Now, the scholarly study of pre-Columbian cultures is most often based on scientific and multidisciplinary methodologies.[2]

Genetics

The haplogroup most commonly associated with Indigenous genetics is Haplogroup Q1a3a (Y-DNA).[3] Researchers have found genetic evidence that the Q1a3a haplogroup has been in South America since at least 18,000 BC.[4] Y-DNA, like mtDNA, differs from other nuclear chromosomes in that the majority of the Y chromosome is unique and does not recombine during meiosis. This has the effect that the historical pattern of mutations can easily be studied.[5] The pattern indicates Indigenous peoples experienced two very distinctive genetic episodes: first with the initial peopling of the Americas and second with European colonization of the Americas.[6][7] The former is the determinant factor for the number of gene lineages and founding haplotypes present in today's Indigenous populations.[7]

Human settlement of the Americas occurred in stages from the Bering Sea coastline, with an initial 20,000-year layover on Beringia for the founding population.[8][9] The micro-satellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicate that certain Amerindian populations have been isolated since the initial colonization of the region.[10] The Na-Dené, Inuit, and Indigenous Alaskan populations exhibit haplogroup Q-M242 (Y-DNA) mutations, however, and are distinct from other Indigenous peoples with various mtDNA mutations.[11][12][13] This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later populations.[14]

Settlement of the Americas

Asian nomadic Paleo-Indians are thought to have entered the Americas via the Bering Land Bridge (Beringia), now the Bering Strait, and possibly along the coast. Genetic evidence found in Indigenous peoples' maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) supports the theory of multiple genetic populations migrating from Asia.[15][16][17] After crossing the land bridge, they moved southward along the Pacific coast[18] and through an interior ice-free corridor.[19] Throughout millennia, Paleo-Indians spread throughout the rest of North and South America.

Exactly when the first people migrated into the Americas is the subject of much debate.[20] One of the earliest identifiable cultures was the Clovis culture, with sites dating from some 13,000 years ago. [21]However, older sites dating back to 20,000 years ago have been claimed. Some genetic studies estimate the colonization of the Americas dates from between 40,000 and 13,000 years ago.[22] The chronology of migration models is currently divided into two general approaches. The first is the short chronology theory with the first movement beyond Alaska into the Americas occurring no earlier than 14,000–17,000 years ago, followed by successive waves of immigrants.[23][24][25][26] The second belief is the long chronology theory, which proposes that the first group of people entered the hemisphere at a much earlier date, possibly 50,000–40,000 years ago or earlier.[27][28][29][30]

Artifacts have been found in both North and South America which have been dated to 14,000 years ago,[31] and accordingly humans have been proposed to have reached Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America by this time. In that case, the Inuit would have arrived separately and at a much later date, probably no more than 2,000 years ago, moving across the ice from Siberia into Alaska.

North America

Lithic and Archaic periods

The North American climate was unstable as the ice age receded during the Lithic stage. It finally stabilized about 10,000 years ago; climatic conditions were then very similar to today's.[32] Within this time frame, roughly about the Archaic Period, numerous archaeological cultures have been identified.

Lithic stage and early Archaic period

The unstable climate led to widespread migration, with early Paleo-Indians soon spreading throughout the Americas, diversifying into many hundreds of culturally distinct tribes.[33] The Paleo-Indians were hunter-gatherers, likely characterized by small, mobile bands consisting of approximately 20 to 50 members of an extended family. These groups moved from place to place as preferred resources were depleted and new supplies were sought.[34] During much of the Paleo-Indian period, bands are thought to have subsisted primarily through hunting now-extinct giant land animals such as mastodon and ancient bison.[35] Paleo-Indian groups carried a variety of tools, including distinctive projectile points and knives, as well as less distinctive butchering and hide-scraping implements.

The vastness of the North American continent, and the variety of its climates, ecology, vegetation, fauna, and landforms, led ancient peoples to coalesce into many distinct linguistic and cultural groups.[36] This is reflected in the oral histories of the indigenous peoples, described by a wide range of traditional creation stories which often say that a given people have been living in a certain territory since the creation of the world.

Throughout thousands of years, paleo-Indian people domesticated, bred, and cultivated many plant species, including crops that now constitute 50–60% of worldwide agriculture.[37] In general, Arctic, Subarctic, and coastal peoples continued to live as hunters and gatherers, while agriculture was adopted in more temperate and sheltered regions, permitting a dramatic rise in population.[32]

Middle Archaic period

After the migration or migrations, it was several thousand years before the first complex societies arose, the earliest emerging about seven to eight thousand years ago.[citation needed] As early as 6500 BCE, people in the Lower Mississippi Valley at the Monte Sano site were building complex earthwork mounds, probably for religious purposes. This is the earliest dated of numerous mound complexes found in present-day Louisiana, Mississippi, and Florida. Since the late twentieth century, archeologists have explored and dated these sites. They have found that they were built by hunter-gatherer societies, whose people occupied the sites on a seasonal basis, and who had not yet developed ceramics. Watson Brake, a large complex of eleven platform mounds, was constructed beginning in 3400 BCE and added to over 500 years. This has changed earlier assumptions that complex construction arose only after societies had adopted agriculture, and become sedentary, with stratified hierarchy and usually ceramics. These ancient people had organized to build complex mound projects under a different social structure.

Late Archaic period

Until the accurate dating of Watson Brake and similar sites, the oldest mound complex was thought to be Poverty Point, also located in the Lower Mississippi Valley. Built about 1500 BCE, it is the centerpiece of a culture extending over 100 sites on both sides of the Mississippi. The Poverty Point site has earthworks in the form of six concentric half-circles, divided by radial aisles, together with some mounds. The entire complex is nearly a mile across.

Mound building was continued by succeeding cultures, who built numerous sites in the middle Mississippi and Ohio River valleys as well, adding effigy mounds, conical and ridge mounds, and other shapes.

Woodland period

The Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures lasted from roughly 1000 BCE to 1000 CE. The term was coined in the 1930s and refers to prehistoric sites between the Archaic period and the Mississippian cultures. The Adena culture and the ensuing Hopewell tradition during this period built monumental earthwork architecture and established continent-spanning trade and exchange networks.

This period is considered a developmental stage without any massive changes in a short period but instead has a continuous development in stone and bone tools, leatherworking, textile manufacture, tool production, cultivation, and shelter construction. Some Woodland people continued to use spears and atlatls until the end of the period when they were replaced by bows and arrows.

Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was spread across the Southeast and Midwest of what is today the United States, from the Atlantic coast to the edge of the plains, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Upper Midwest, although most intensively in the area along the Mississippi River and Ohio River. One of the distinguishing features of this culture was the construction of complexes of large earthen mounds and grand plazas, continuing the mound-building traditions of earlier cultures. They grew maize and other crops intensively, participated in an extensive trade network, and had a complex stratified society. The Mississippians first appeared around 1000 CE, following and developing out of the less agriculturally intensive and less centralized Woodland period. The largest urban site of these people, Cahokia—located near modern East St. Louis, Illinois—may have reached a population of over 20,000. Other chiefdoms were constructed throughout the Southeast, and its trade networks reached to the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico. At its peak, between the 12th and 13th centuries, Cahokia was the most populous city in North America. (Larger cities did exist in Mesoamerica and the Andes.) Monks Mound, the major ceremonial center of Cahokia, remains the largest earthen construction of the prehistoric Americas. The culture reached its peak in about 1200–1400 CE, and in most places, it seems to have been in decline before the arrival of Europeans.[citation needed]

Many Mississippian peoples were encountered by the expedition of Hernando de Soto in the 1540s, mostly with disastrous results for both sides. Unlike the Spanish expeditions in Mesoamerica, which conquered vast empires with relatively few men, the de Soto expedition wandered the American Southeast for four years, becoming more bedraggled, losing more men and equipment, and eventually arriving in Mexico as a fraction of its original size. The local people fared much worse though, as the fatalities of diseases introduced by the expedition devastated the populations and produced much social disruption. By the time Europeans returned a hundred years later, nearly all of the Mississippian groups had vanished, and vast swaths of their territory were virtually uninhabited.[38]

-

Monks Mound of Cahokia (UNESCO World Heritage Site) in summer. The concrete staircase follows the approximate course of the ancient wooden stairs.

-

An artistic recreation of The Kincaid site from the prehistoric Mississippian culture as it may have looked at its peak 1050–1400 CE

-

Engraved stone palette from Moundville, illustrating two horned rattlesnakes, perhaps referring to The Great Serpent of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

-

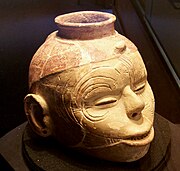

A human head effigy pot from the Nodena site

Ancestral Puebloans

The Ancestral Puebloans thrived in what is now the Four Corners region in the United States. It is commonly suggested that the culture of the Ancestral Puebloans emerged during the Early Basketmaker II Era during the 12th century BCE. The Ancestral Puebloans were a complex Oasisamerican society that constructed kivas, multi-story houses, and apartment blocks made from stone and adobe, such as the Cliff Palace of Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado and the Great Houses in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. The Puebloans also constructed a road system that stretched from Chaco Canyon to Kutz Canyon in the San Juan Basin.[39] The Ancestral Puebloans are also known as "Anasazi", though the term is controversial, as the present-day Pueblo peoples consider the term to be derogatory, due to the word tracing its origins to a Navajo word meaning "ancestor enemies".[40]

Hohokam

The Hohokam thrived in the Sonoran desert in what is now the U.S. state of Arizona and the Mexican state of Sonora. The Hohokam were responsible for the construction of a series of irrigation canals that led to the successful establishment of Phoenix, Arizona via the Salt River Project. The Hohokam also established complex settlements such as Snaketown, which served as an important commercial trading center. After 1375 CE, Hohokam society collapsed and the people abandoned their settlements, likely due to drought.

Mogollon

The Mogollon resided in the present-day states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas as well as Sonora and Chihuahua. Like most other cultures in Oasisamerica, the Mogollon constructed sophisticated kivas and cliff dwellings. In the village of Paquimé, the Mogollon are revealed to have housed pens for scarlet macaws, which were introduced from Mesoamerica through trade.[41]

Sinagua

The Sinagua were hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists who lived in central Arizona. Like the Hohokam, they constructed kivas and great houses as well as ballcourts. Several of the Sinagua ruins include Montezuma Castle, Wupatki, and Tuzigoot.

Salado

The Salado resided in the Tonto Basin in southeastern Arizona from 1150 CE to the 15th century. Archaeological evidence suggests that they traded with far-away cultures, as evidenced by the presence of seashells from the Gulf of California and macaw feathers from Mexico. Most of the cliff dwellings constructed by the Salado are primarily located in Tonto National Monument.

Iroquois

The Iroquois League of Nations or "People of the Long House" was a politically advanced, democratic society, which is thought by some historians to have influenced the United States Constitution,[42][43] with the Senate passing a resolution to this effect in 1988.[44] Other historians have contested this interpretation and believe the impact was minimal or did not exist, pointing to numerous differences between the two systems and the ample precedents for the constitution in European political thought.[45][46][47]

Calusa

The Calusa were a complex paramountcy/kingdom that resided in southern Florida. Instead of agriculture, the Calusa economy relied on abundant fishing. According to Spanish sources, the "king's house" at Mound Key was large enough to house 2,000 people.[48] The Calusa ultimately collapsed into extinction at around 1750 after succumbing to diseases introduced by the Spanish colonists.

Wichita

The Wichita people were a loose confederation that consisted of sedentary agriculturalists and hunter-gatherers who resided in the eastern Great Plains. They lived in permanent settlements and even established a city called Etzanoa, which had a population of 20,000 people. The city was eventually abandoned around the 18th century after it was encountered by Spanish conquistadors Jusepe Gutierrez and Juan de Oñate.

Historic tribes

When the Europeans arrived, Indigenous peoples of North America had a wide range of lifeways from sedentary, agrarian societies to semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer societies. Many formed new tribes or confederations in response to European colonization. These are often classified by cultural regions, loosely based on geography. These can include the following:

- Arctic, including Aleut, Inuit, and Yupik peoples

- Subarctic

- Northeastern Woodlands

- Southeastern Woodlands

- Great Plains

- Great Basin

- Northwest Plateau

- Northwest Coast

- California

- Southwest

Numerous pre-Columbian societies were sedentary, such as the Tlingit, Haida, Chumash, Mandan, Hidatsa, and others, and some established large settlements, even cities, such as Cahokia, in what is now Illinois.

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is the region extending from central Mexico south to the northwestern border of Costa Rica that gave rise to a group of stratified, culturally related agrarian civilizations spanning an approximately 3,000-year period before the visits to the Caribbean by Christopher Columbus. Mesoamerican is the adjective generally used to refer to that group of pre-Columbian cultures. This refers to an environmental area occupied by an assortment of ancient cultures that shared religious beliefs, art, architecture, and technology in the Americas for more than three thousand years. Between 2000 and 300 BCE, complex cultures began to form in Mesoamerica. Some matured into advanced pre-Columbian Mesoamerican civilizations such as the Olmec, Teotihuacan, Mayas, Zapotecs, Mixtecs, Huastecs, Purepecha, Toltecs, and Mexica/Aztecs. The Mexica civilization is also known as the Aztec Triple Alliance since they were three smaller kingdoms loosely united together.[49]

These Indigenous civilizations are credited with many inventions: building pyramid temples, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, writing, highly accurate calendars, fine arts, intensive agriculture, engineering, an abacus calculator, and complex theology. They also invented the wheel, but it was used solely as a toy. In addition, they used native copper, silver, and gold for metalworking.

Archaic inscriptions on rocks and rock walls all over northern Mexico (especially in the state of Nuevo León) demonstrate an early propensity for counting. Their number system was base 20 and included zero. These early count markings were associated with astronomical events and underscore the influence that astronomical activities had upon Mesoamerican people before the arrival of Europeans. Many of the later Mesoamerican civilizations carefully built their cities and ceremonial centers according to specific astronomical events.

The biggest Mesoamerican cities, such as Teotihuacan, Tenochtitlan, and Cholula, were among the largest in the world. These cities grew as centers of commerce, ideas, ceremonies, and theology, and they radiated influence outwards onto neighboring cultures in central Mexico.

While many city-states, kingdoms, and empires competed with one another for power and prestige, Mesoamerica can be said to have had five major civilizations: the Olmecs, Teotihuacan, the Toltecs, the Mexica, and the Mayas. These civilizations (except for the politically fragmented Maya) extended their reach across Mesoamerica—and beyond—like no others. They consolidated power and distributed influence in matters of trade, art, politics, technology, and theology. Other regional power players made economic and political alliances with these civilizations over 4,000 years. Many made war with them, but almost all peoples found themselves within one of their spheres of influence.

Regional communications in ancient Mesoamerica have been the subject of considerable research. There is evidence of trade routes starting as far north as the Mexico Central Plateau, and going down to the Pacific coast. These trade routes and cultural contacts then went on as far as Central America. These networks operated with various interruptions from pre-Olmec times and up to the Late Classical Period (600–900 CE).

Olmec civilization

The earliest known civilization in Mesoamerica is the Olmec. This civilization established the cultural blueprint by which all succeeding indigenous civilizations would follow in Mexico. Pre-Olmec civilization began with the production of pottery in abundance, around 2300 BCE in the Grijalva River delta. Between 1600 and 1500 BCE, the Olmec civilization had begun, with the consolidation of power at their capital, a site today known as San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán near the coast in southeast Veracruz.[50] The Olmec influence extended across Mexico, into Central America, and along the Gulf of Mexico. They transformed many peoples' thinking toward a new way of government, pyramid temples, writing, astronomy, art, mathematics, economics, and religion. Their achievements paved the way for the Maya civilization and the civilizations in central Mexico.

Teotihuacan civilization

The decline of the Olmec resulted in a power vacuum in Mexico. Emerging from that vacuum was Teotihuacan, first settled in 300 BCE. By 150 CE, Teotihuacan had risen to become the first true metropolis of what is now called North America. Teotihuacan established a new economic and political order never before seen in Mexico. Its influence stretched across Mexico into Central America, founding new dynasties in the Maya cities of Tikal, Copan, and Kaminaljuyú. Teotihuacan's influence over the Maya civilization cannot be overstated: it transformed political power, artistic depictions, and the nature of economics. Within the city of Teotihuacan was a diverse and cosmopolitan population. Most of the regional ethnicities of Mexico were represented in the city, such as Zapotecs from the Oaxaca region. They lived in apartment communities where they worked their trades and contributed to the city's economic and cultural prowess. Teotihuacan's economic pull impacted areas in northern Mexico as well. It was a city whose monumental architecture reflected a monumental new era in Mexican civilization, declining in political power about 650 CE—but lasting in cultural influence for the better part of a millennium, to around 950 CE.

Maya civilization

Contemporary Teotihuacan's greatness was that of the Maya civilization. The period between 250 CE and 650 CE was a time of intense flourishing of Maya civilized accomplishments. While the many Maya city-states never achieved political unity on the order of the central Mexican civilizations, they exerted tremendous intellectual influence upon Mexico and Central America. The Maya built some of the most elaborate cities on the continent and made innovations in mathematics, astronomy, and calendrics. The Maya also developed the only true writing system[citation needed] native to the Americas using pictographs and syllabic elements in the form of texts and codices inscribed on stone, pottery, wood, or perishable books made from bark paper.

Huastec civilizationedit

The Huastecs were a Maya ethnic group that migrated northwards to the Gulf Coast of Mexico.[51] The Huastecs are considered to be distinct from the Maya civilization, as they separated from the main Maya branch at around 2000 BC and did not possess the Maya script.[52][53] Other accounts also suggest that the Huastecs migrated as a result of the Classic Maya collapse around the year 900 AD.

Zapotec civilizationedit

The Zapotecs were a civilization that thrived in the Oaxaca Valley from the late 6th century BC until their downfall at the hands of the Spanish conquistadors. The city of Monte Albán was an important religious center for the Zapotecs and served as the capital of the empire from 700 BCE to 700 CE. The Zapotecs resisted the expansion of the Aztecs until they were subjugated in 1502 under Aztec emperor Ahuitzotl. After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Zapotecs resisted Spanish rule until King Cosijopii I surrendered in 1563.

Mixtec civilizationedit

Like the Zapotecs, the Mixtecs thrived in the Oaxaca Valley. The Mixtecs consisted of separate independent kingdoms and city-states, rather than a single unified empire. The Mixtecs would eventually be conquered by the Aztecs until the Spanish conquest. The Mixtecs saw the Spanish conquest as an opportunity for liberation and established agreements with the conquistadors that allowed them to preserve their cultural traditions, though relatively few sections resisted Spanish rule.

Totonac civilizationedit

The Totonac civilization was concentrated in the present-day states of Veracruz and Puebla. The Totonacs were responsible for the establishment of cities, such as El Tajín as important commercial trading centers. The Totonacs would later assist in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire as an opportunity to liberate themselves from Aztec military imperialism.

Toltec civilizationedit

The Toltec civilization was established in the 8th century CE. The Toltec Empire expanded its political borders to as far south as the Yucatán peninsula, including the Maya city of Chichen Itza. The Toltecs established vast trading relations with other Mesoamerican civilizations in Central America and the Puebloans in present-day New Mexico. During the Post-Classic era, the Toltecs suffered a subsequent collapse in the early 12th century, due to famine and civil war.[54] The Toltec civilization was so influential to the point where many groups such as the Aztecs claimed to be descended from.[55][56]

Aztec/Mexica/Triple Alliance civilizationedit

With the decline of the Toltec civilization came political fragmentation in the Valley of Mexico. Into this new political game of contenders to the Toltec throne stepped outsiders: the Mexica. They were also a desert people, one of seven groups who formerly called themselves "Azteca", in memory of Aztlán, but they changed their name after years of migrating. Since they were not from the Valley of Mexico, they were initially seen as crude and unrefined in the ways of the Nahua civilization. Through political maneuvers and ferocious martial skills, they managed to rule Mexico as the head of the 'Triple Alliance' which included two other Aztec cities, Tetxcoco and Tlacopan.

Latecomers to Mexico's central plateau, the Mexica thought of themselves, nevertheless, as heirs of the civilizations that had preceded them. For them, arts, sculpture, architecture, engraving, feather-mosaic work, and the calendar, were bequest from the former inhabitants of Tula, the Toltecs.

The Mexica-Aztecs were the rulers of much of central Mexico by about 1400 (while Yaquis, Coras, and Apaches commanded sizable regions of northern desert), having subjugated most of the other regional states by the 1470s. At their peak, the Valley of Mexico where the Aztec Empire presided, saw a population growth that included nearly 1 million people during the late Aztec period (1350–1519).[57]

Their capital, Tenochtitlan, is the site of modern-day Mexico City. At its peak, it was one of the largest cities in the world with population estimates of 200,000–300,000.[58] The market established there was the largest ever seen by the conquistadores on arrival.

Tarascan/Purépecha civilizationedit

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Pre-ColumbianText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk