A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Culture of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

|

| Visual arts |

| Performing arts |

| Languages and literature |

| Sports |

| Other |

Ottoman architecture is an architectural style or tradition that developed under the Ottoman Empire over a long period,[1] undergoing some significant changes during its history.[2] It first emerged in northwestern Anatolia in the late 13th century[3] and developed from earlier Seljuk Turkish architecture, with influences from Byzantine and Iranian architecture along with other architectural traditions in the Middle East.[4] Early Ottoman architecture experimented with multiple building types over the course of the 13th to 15th centuries, progressively evolving into the classical Ottoman style of the 16th and 17th centuries. This style was a mixture of native Turkish tradition and influences from the Hagia Sophia, resulting in monumental mosque buildings focused around a high central dome with a varying number of semi-domes.[5][6][7] The most important architect of the classical period is Mimar Sinan, whose major works include the Şehzade Mosque, Süleymaniye Mosque, and Selimiye Mosque.[7][8] The second half of the 16th century also saw the apogee of certain decorative arts, most notably in the use of Iznik tiles.[9]

Beginning in the 18th century, Ottoman architecture was opened to external influences, particularly Baroque architecture in Western Europe. Changes appeared during the style of the Tulip Period, followed by the emergence of the Ottoman Baroque style in the 1740s.[10][11] The Nuruosmaniye Mosque is one of the most important examples of this period.[12][13] The architecture of the 19th century saw more influences imported from Western Europe, brought in by architects such as those from the Balyan family.[14] Empire style and Neoclassical motifs were introduced and a trend towards eclecticism was evident in many types of buildings, such as the Dolmabaçe Palace.[15] The last decades of the Ottoman Empire saw the development of a new architectural style called neo-Ottoman or Ottoman revivalism, also known as the First National Architectural Movement, by architects such as Mimar Kemaleddin and Vedat Tek.[16][14]

Ottoman dynastic patronage was concentrated in the historic capitals of Bursa, Edirne, and Istanbul (Constantinople), as well as in several other important administrative centers such as Amasya and Manisa. It was in these centers that most important developments in Ottoman architecture occurred and that the most monumental Ottoman architecture can be found.[17] Major religious monuments were typically architectural complexes, known as a külliye, that had multiple components providing different services or amenities. In addition to a mosque, these could include a madrasa, a hammam, an imaret, a sebil, a market, a caravanserai, a primary school, or others.[18] Ottoman constructions were still abundant in Anatolia and in the Balkans (Rumelia), but in the more distant Middle Eastern and North African provinces older Islamic architectural styles continued to hold strong influence and were sometimes blended with Ottoman styles.[19][20]

Early Ottoman period

Early developments

The first Ottomans were established in northwest Anatolia near the borders of the Byzantine Empire. Their position at this frontier encouraged influences from Byzantine architecture and other ancient remains in the region, and there were examples of similar architectural experimentation by the other local dynasties of the region.[21] One of the early Ottoman stylistic distinctions that emerged was a tradition of designing more complete façades in front of mosques, especially in the form of a portico with arches and columns.[21] Another early distinction was the reliance on domes.[22] The first Ottoman structures were built in Söğüt, the earliest Ottoman capital, and in nearby Bilecik, but they have not survived in their original form. They include a couple of small mosques and a mausoleum built in Ertuğrul's time (late 13th century).[23] Bursa was captured in 1326 by the Ottoman leader Orhan. It served as the Ottoman capital until 1402, becoming a major center of patronage and construction.[24] Orhan also captured İznik in 1331, turning it into another early center of Ottoman art.[25] In this early period there were generally three types of mosques: the single-domed mosque, the T-plan mosque, and the multi-unit or multi-dome mosque.[22]

Single-domed mosques

The Hacı Özbek Mosque (1333) in İznik is the oldest Ottoman mosque with an inscription that documents its construction.[21] It is also the first example of an Ottoman single-domed mosque, consisting of a square chamber covered by a dome.[26] It is built in alternating layers of brick and cut stone, a technique which was likely copied from Byzantine examples and recurred in other Ottoman structures.[27] The dome is covered in terracotta tiles, which was also a custom of early Ottoman architecture before later Ottoman domes were covered in lead.[27] Other structures from the time of Orhan were built at İznik, Bilecik, and in Bursa.[28] Single-domed mosques continued to be built after this, such as the example of the Green Mosque in Iznik (1378–1391), which was built by an Ottoman pasha. The Green Mosque of İznik is the first Ottoman mosque for which the name of the architect (Hacı bin Musa) is known.[29] The main dome covers a square space, and as a result the transition between the round base of the dome and the square chamber below is achieved through a series of triangular carvings known as "Turkish triangles", a type of pendentive which was common in Anatolian Seljuk and early Ottoman architecture.[18][30][31] An example of a single-domed mosque with a much larger dome can be found in the Yildirim Bayezid I Mosque in Mudurnu, which dates from around 1389. The ambitious dome, with a diameter of 20 meters, was comparable to much later Ottoman mosques but it had to be built closer to the ground in order to be stable. Instead of Turkish triangles the transition is made through squinches that start low along the walls.[32]

- Single-domed mosques

-

Hacı Özbek Mosque in Iznik (1333), one of the earliest surviving Ottoman mosques

-

Green Mosque in Iznik (1378–1391)

-

Green Mosque interior: "Turkish triangles" form the transition from dome to square chamber[30]

-

Interior of Yildirim Bayezid Mosque in Mudurnu (circa 1389)

"T-plan" mosques or zaviyes

In 1334–1335 Orhan built a mosque outside the Yenişehir Gate in İznik which no longer stands but has been excavated and studied by archeologists. It is significant as the earliest known example of a type of building called a zaviye (a cognate of Arabic zawiya), "T-plan" mosque, or "Bursa-type" mosque.[33] This type of building is characterized by a central courtyard, typically covered by a dome, with iwans (domed or vaulted halls that are open to the courtyard) on three sides, one of which is oriented towards the qibla (direction of prayer) and contains the mihrab (wall niche symbolizing the qibla). The front façade usually incorporated a portico along its entire width. The iwans on the side and the other various rooms attached to these buildings may have served to house Sufi students and traveling dervishes, since the Sufi brotherhoods were one of the main supporters of the early Ottomans.[34] Variations of this floor plan were the most common type of major religious structure sponsored by the early Ottoman elites. The "Bursa-type" label comes from the fact that multiple examples of this kind were built in and around Bursa, including the Orhan Gazi Mosque (1339), the Hüdavendigar (Murad I) Mosque (1366–1385), the Yildirim Bayezid I Mosque (completed in 1395), and the Green Mosque built by Mehmed I.[35][28][18] The Green Mosque, begun in 1412 and completed in 1424,[36] is notable for its extensive tile decoration in the cuerda seca technique. It is the first instance of lavish tile decoration in Ottoman architecture.[36] These mosques were all part of larger religious complexes (külliyes) that included other structures offering services such as madrasas (Islamic colleges), hammams (public bathhouses), and imarets (charitable kitchens).[18]

Notable examples of T-plan buildings beyond Bursa include the Firuz Bey Mosque in Milas, built in 1394 by a local Ottoman governor,[37][38] and the Nilüfer Hatun Imaret in Iznik, originally a zaviye built in 1388 to honor Murad I's mother.[39] The Firuz Bey Mosque is notable for being built in stone and featuring carved decoration of high quality.[37][40] Two other T-plan examples, the Beylerbeyi Mosque in Edirne (1428–1429) and the Yahşi Bey Mosque in Izmir (circa 1441–1442), are both significant as later T-plan structures with more complex decorative roof systems. In both buildings the usual side iwans are replaced by separate halls accessed through doorways from the central space. As a result, prayers were probably only held in the qibla-oriented iwan, demonstrating how zaviye buildings were often not designed as simple mosques but had more complex functions instead. In both buildings the qibla iwan is semi-octagonal in shape and is covered by a semi-dome. Large muqarnas carvings, grooving, or other geometrical carvings decorate the domes and semi-domes.[41]

- T-plan mosques and buildings

-

Orhan Gazi Mosque in Bursa (1339): exterior and front portico

-

Orhan Gazi Mosque: interior prayer hall, view towards the qibla

-

Hüdavendigar Mosque in Bursa (1366–1385): interior of the prayer hall

-

Nilüfer Hatun Imaret in Iznik (1388)

-

Yıldırım Bayezid I Mosque in Bursa (1395): exterior and portico

-

Yıldırım Bayezid I Mosque: interior view towards the qibla iwan

-

Firuz Bey Mosque in Milas (1394): exterior façade

-

Green Mosque in Bursa (1412–1424): exterior façade and entrance portal

-

Green Mosque: interior

-

Green Mosque: mihrab and tile decoration

-

Green Tomb in Bursa (1412–24), part of the Green Mosque complex

-

Interior of the Green Tomb

-

Beylerbeyi Mosque in Edirne (1428–1429): interior view of the qibla iwan

Multi-dome buildings

The most unusual mosque of this period is the congregational mosque known as the Grand Mosque of Bursa or Ulu Cami. The mosque was commissioned by Bayezid I and funded by the booty from his victory at the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396. It was finished a few years later in 1399–1400.[42] It is a multi-dome mosque, consisting of a large hypostyle hall divided into twenty equal bays in a rectangular four-by-five grid, each covered by a dome supported by stone piers. The dome over the middle bay of the second row has an oculus and its floor is occupied by a fountain, serving a role similar to the sahn (courtyard) in the mosques of other regions.[42] The minbar (pulpit) of the mosque is among the finest examples of early Ottoman wooden minbars made with the kündekari technique, in which pieces of wood are fitted together without nails or glue. Its surfaces are decorated with inscriptions, floral (arabesque) motifs, and geometric motifs.[43]

After Bayezid I suffered a disastrous defeat in 1402 at the Battle of Ankara against Timur, the capital was moved to Edirne in Thrace. Another multi-dome congregational mosque was begun here by Suleyman Çelebi in 1403 and finished by Mehmed I in 1414. It is known today as the Old Mosque (Eski Cami). It is slightly smaller than the Bursa Grand Mosque, consisting of a square floor plan divided into nine domed bays supported by four piers.[42][44] This was the last major multi-dome mosque built by the Ottomans (with some exceptions such as the later Piyale Pasha Mosque). In later periods, the multi-dome building type was adapted for use in non-religious buildings instead.[45] One example of this is the bedesten – a kind of market hall at the center of a bazaar – which Bayezid I built in Bursa during his reign.[46] A similar bedesten was built in Edirne by Mehmed I between 1413 and 1421.[46]

- Multi-domed mosques and buildings

-

Grand Mosque of Bursa (1396–1400)

-

Interior of the Grand Mosque of Bursa

-

Wooden minbar of the Grand Mosque of Bursa

-

Old Mosque of Edirne (1403–1414)

-

Interior of the Old Mosque of Edirne

-

Interior of the Bedesten of Bursa (with modern-day shops)

-

Exterior view of the Bedesten of Edirne

-

Koca Mahmut Paşa Camii (build 1451-1494), Sofia

Murad II and the Üç Şerefeli Mosque

The period of Murad II (between 1421 and 1451) saw the continuation of some traditions and the introduction of new innovations. Although the capital was at Edirne, Murad II had his funerary complex (the Muradiye Complex) built in Bursa between 1424 and 1426.[47] It included a mosque (heavily restored in the 19th century), a madrasa, an imaret, and a mausoleum. Its cemetery developed into a royal necropolis when later mausoleums were built here, although Murad II was the only sultan buried here.[48][49] Murad II's mausoleum is unique among royal Ottoman tombs as its central dome has an opening to the sky and his son's mausoleum was built directly adjacent to it, as per the sultan's last wishes.[48][50] The madrasa of the complex is one of the most architecturally accomplished of this period and one of the few of its kind from this period to survive.[48][51] It has a square courtyard with a central fountain (shadirvan) surrounded by a domed portico, behind which are vaulted rooms. On the southeast side of the courtyard is a large domed classroom (dershane), whose entrance façade (facing the courtyard) features some tile decoration.[48] In Edirne Murad II built another zaviye for Sufis in 1435, now known as the Murad II Mosque. It repeats the Bursa-type plan and also features rich tile decoration similar to the Green Mosque in Bursa, as well as new blue-and-white tiles with Chinese influences.[52][53]

The most important mosque of this period is the Üç Şerefeli Mosque, begun by Murad II in 1437 and finished in 1447.[54][55] It has a very different design from earlier mosques. The floor plan is nearly square but is divided between a rectangular courtyard and a rectangular prayer hall. The courtyard has a central fountain and is surrounded by a portico of arches and domes, with a decorated central portal leading into the courtyard from the outside and another one leading from the courtyard into the prayer hall. The prayer hall is centered around a huge dome which covers most of the middle part of the hall, while the sides of the hall are covered by pairs of smaller domes. The central dome, 24 meters in diameter (or 27 meters according to Kuban[56]), is much larger than any other Ottoman dome built before this.[57] On the outside, this results in an early example of the "cascade of domes" visual effect seen in later Ottoman mosques, although the overall arrangement here is described by Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom as not yet successful compared to later examples.[54] The mosque has a total of four minarets, arranged around the four corners of the courtyard. Its southwestern minaret was the tallest Ottoman minaret built up to that time and features three balconies, from which the mosque's name derives.[58]

The overall form of the Üç Şerefeli Mosque, with its central-dome prayer hall, arcaded court with fountain, minarets, and tall entrance portals, foreshadowed the features of later Ottoman mosque architecture.[54] It has been described as a "crossroads of Ottoman architecture",[54] marking the culmination of architectural experimentation with different spatial arrangements during the period of the Beyliks and the early Ottomans.[54][55][57] Kuban describes it as the "last stage in Early Ottoman architecture", while the central dome plan and the "modular" character of its design signaled the direction of future Ottoman architecture in Istanbul.[59]

- Complexes of Murad II

-

Tomb of Murad II at the Muradiye Complex in Bursa (circa 1426)

-

Entrance to the Murad II Medrese in Bursa (circa 1426)

-

Remains of tile and fresco decoration in the Murad II Mosque in Edirne (circa 1435)

-

Üç Şerefeli Mosque in Edirne (1437–1447): exterior

-

Üç Şerefeli Mosque: courtyard

-

Üç Şerefeli Mosque: interior

Mehmed II and early Ottoman Istanbul

Mehmed II succeeded his father temporarily in 1444 and definitively in 1451. He is also known as "Fatih" or the Conqueror after his conquest of Constantinople in 1453, which brought the remains of the Byzantine Empire to an end. Mehmed was strongly interested in Turkish, Persian, and European cultures and sponsored artists and writers at his court.[60] Before the 1453 conquest his capital remained at Edirne, where he completed a new palace for himself in 1452–53.[60] He made extensive preparations for the siege, including the construction of a large fortress known as Rumeli Hisarı on the western shore of the Bosphorus, begun in 1451-52 and completed shortly before the siege in 1453.[61] This was located across from an older fortress on the eastern shore known as Anadolu Hisarı, built by Bayezid I in the 1390s for an earlier siege, and was designed to cut off communications to the city through the Bosphorus.[62] Rumeli Hisarı remains one of the most impressive medieval Ottoman fortifications. It consists of three large round towers connected by curtain walls, with an irregular layout adapted to the topography of the site. A small mosque was built inside the fortified enclosure. The towers once had conical roofs, but these disappeared in the 19th century.[61]

After the conquest of Constantinople (now known as Istanbul), one of Mehmed's first constructions in the city was a palace, known as the Old Palace (Eski Saray), built in 1455 on the site of what is now the main campus of Istanbul University.[60] At the same time Mehmed built another fortress, Yedikule ("Seven Towers"), at the south end of the city's land walls in order to house and protect the treasury. It was completed in 1457–1458. Unlike Rumeli Hisarı, it has a regular layout in the shape of a five-pointed star, possibly of Italian inspiration.[63][60] In order to revitalize commerce, Mehmed built the first bedesten in Istanbul between 1456 and 1461, variously known as the Inner Bedesten (Iç Bedesten), Old Bedesten (Eski Bedesten or Bedesten-i Atik), or the Jewellers' Bedesten (Cevahir Bedesteni).[64][65] A second bedesten, the Sandal Bedesten, also known as the Small Bedesten (Küçük Bedesten) or New Bedesten (Bedesten-i Cedid), was built by Mehmed about a dozen years later.[64][66] These two bedestens, each consisting of a large multi-dome hall, form the original core of what is now the Grand Bazaar, which grew around them over the following generations.[64][66] The nearby Tahtakale Hammam, the oldest hammam (public bathhouse) of the city, also dates from around this time.[67] The only other documented hammams in the city which date from the time of Mehmet II are the Mahmut Pasha Hamam (part of the Mahmut Pasha Mosque's complex) built in 1466[67][68] and the Gedik Ahmet Pasha Hamam built around 1475.[62]

- Early Ottoman buildings in Istanbul under Mehmed II

-

Yedikule Fortress in Istanbul (circa 1458)

-

Interior of the Sandal Bedesten in the Grand Bazaar, Istanbul

-

Interior of the Tahtakale Hamam (dome is original but the balconies are modern)

-

Mahmut Pasha Hamam, Istanbul (1466)

-

Mahmut Pasha Hamam: dome interior

In 1459 Mehmed II began construction of a second palace, known as the New Palace (Yeni Saray) and later as the Topkapi Palace ("Cannon-Gate Palace"), on the site of the former acropolis of Byzantium, a hill overlooking the Bosphorus.[69] The palace was mostly laid out between 1459 and 1465.[62] Initially it remained mostly an administrative palace, while the residence of the sultan remained at the Old Palace. It only became a royal residence in the 16th century, when the harem section was constructed.[62] The palace has been repeatedly modified over subsequent centuries by different rulers, with the palace today now representing an accumulation of different styles and periods. Its overall layout appears highly irregular, consisting of several courtyards and enclosures within a precinct delimited by an outer wall. The seemingly irregular layout of the palace was in fact a reflection of a clear hierarchical organization of functions and private residences, with the innermost areas reserved for the privacy of the sultan and his innermost circle.[69] Among the structures today that date from Mehmet's time is the Fatih Kiosk or Pavilion of Mehmed II, located on the east side of the Third Court and built in 1462–1463.[70] It consists of a series of domed chambers preceded by an arcaded portico on the palace-facing side. It stands on top of a heavy substructure built into the hillside overlooking the Bosphorus. This lower level also originally served as a treasury. The presence of strongly-built foundation walls and substructures like this was a common characteristic of Ottoman construction in this palace as well as other architectural complexes.[71] Bab-ı Hümayun, the main outer entrance to the palace grounds, dates from Mehmet II's time according to an inscription that gives the date 1478–1479, but it was covered in new marble during the 19th century.[72][73] Kuban also argues that the Babüsselam (Gate of Salution), the gate to the Second Court flanked by two towers, dates to the time Mehmed II.[74] Within the outer gardens of the palace, Mehmed II commissioned three pavilions built in three different styles. One pavilion was in Ottoman style, another in Greek style, and a third one in a Persian style.[69][73] Of these, only the Persian pavilion, known as the Tiled Kiosk (Çinili Köşk), has survived. It was completed in September or October 1472 and its name derives from its rich tile decoration, including the first appearance of Iranian-inspired banna'i tilework in Istanbul. The vaulting and cruciform layout of the building's interior is also based on Iranian precedents, while the exterior is fronted by a tall portico. Although not much is known about the builders, they were likely of Iranian origin, as historical documents indicate the presence of tilecutters from Khorasan.[69]

- Palace architecture of Mehmed II

-

Bab-ı Hümayun, the outer gate to the Topkapi Palace (1478–1479, with later renovations)

-

Babüsselam, the gate to the Second Court in Topkapi Palace

-

Fatih Kiosk in the Third Court of Topkapi Palace (1462–1463)

-

Tiled Kiosk in the outer gardens of Topkapi Palace (1472)

-

Tile decoration of the Tiled Kiosk

Mehmed's largest contribution to religious architecture was the Fatih Mosque complex in Istanbul, built from 1463 to 1470. It was part of a very large külliye which also included a tabhane (guesthouse for travelers), an imaret, a darüşşifa (hospital), a caravanserai (hostel for traveling merchants), a mektep (primary school), a library, a hammam, shops, a cemetery with the founder's mausoleum, and eight madrasas along with their annexes.[75][62] Not all of these structures have survived to the present day. The buildings largely ignored any existing topography and were arranged in a strongly symmetrical layout on a vast square terrace with the monumental mosque at its center.[76] The architect of the mosque complex was Usta Sinan, known as Sinan the Elder.[77] It was located on the Fourth Hill of Istanbul, which was until then occupied by the ruined Byzantine Church of the Holy Apostles.[77] Unfortunately, much of the mosque was destroyed by an earthquake in 1766, causing it to be largely rebuilt by Mustafa III in a significantly altered form shortly afterwards. Only the walls and porticos of the mosque's courtyard and the marble entrance to the prayer hall have survived overall from the original mosque.[78][79][80] The form of the rest of the mosque has had to be reconstructed by scholars using historical sources and illustrations.[77][80] The design likely reflected the combination of the Byzantine church tradition (especially the Hagia Sophia) with the Ottoman tradition that had evolved since the early imperial mosques of Bursa and Edirne.[76][81] Drawing on the ideas established by the earlier Üç Şerefeli Mosque, the mosque consisted of a rectangular courtyard with a surrounding gallery leading to a domed prayer hall. The prayer hall consisted of a large central dome with a semi-dome behind it (on the qibla side) and flanked by a row of three smaller domes on either side.[76]

The reign of Bayezid II

After Mehmed II, the reign of Bayezid II (1481–1512) is again marked by extensive architectural patronage, of which the two most outstanding and influential examples are the Bayezid II Complex in Edirne and the Bayezid II Mosque in Istanbul.[82] While it was a period of further experimentation, the Mosque of Bayezid II in Amasya, completed in 1486, was still based on the Bursa-type plan, representing the last and largest imperial mosque in this style.[7] Doğan Kuban regards the constructions of Bayzezid II as also constituting deliberate attempts at urban planning, extending the legacy of the Fatih Mosque complex in Istanbul.[83]

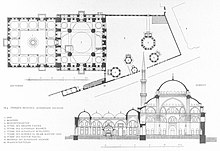

The Bayezid II Complex in Edirne is a complex (külliye) of buildings including a mosque, a darüşşifa, an imaret, a madrasa, a tımarhane (asylum for the mentally ill), two tabhanes, a bakery, latrines, and other services, all linked together on the same site. It was commissioned by Bayezid II in 1484 and completed in 1488 under the direction of the architect Hayrettin.[84][85] The various structures of the complex have relatively simple but strictly geometrical floor plans, built of stone with lead-covered roofs, with only sparse decoration in the form of alternating coloured stone around windows and arches.[86][7] This has been described as an "Ottoman classical architectural aesthetic at an early stage in its development".[7] The mosque lies at the heart of the complex. It has an austere square prayer hall covered by a large high dome. The hall is preceded by a rectangular courtyard with a fountain and a surrounding arcade. The darüşşifa, whose function was the main motivation behind Bayezid's construction of the complex, has two inner courtyards that lead to a structure with a hexagonal floor plan featuring small domed rooms arranged around a larger central dome.[87]

The Bayezid II Mosque in Istanbul was built between 1500 and 1505 under the direction of the architect Ya'qub or Yakubshah (although Hayrettin is also mentioned in documents).[88][7][89] It too was part of a larger complex, which included a madrasa (serving today as a Museum of Turkish Calligraphy Art), a monumental hammam (the Bayezid II Hamam), hospices, an imaret, a caravanserai, and a cemetery around the sultan's mausoleum.[90][91] The mosque itself, the largest building, once again consists of a courtyard leading to the square prayer hall. However, the prayer hall now makes use of two semi-domes aligned with the main central dome, while the side aisles are each covered by four smaller domes. Compared to earlier mosques, this results in a much more sophisticated "cascade of domes" effect for the building's exterior profile, likely reflecting influences from the Hagia Sophia and the original (now disappeared) Fatih Mosque.[92] The mosque is the culmination of this period of architectural exploration under Bayezid II and the last step towards the classical Ottoman style.[93][94] The deliberate arrangement of established Ottoman architectural elements into a strongly symmetrical design is one aspect which denotes this evolution.[94]

- Complexes of Bayezid II

-

Bayezid II Mosque in Amasya (1486)

-

Bayezid II Complex in Edirne (1484–1488)

-

Interior of the mosque at the Bayezid II Complex in Edirne

-

Inner courtyard of the darüşşifa at the Bayezid II Complex in Edirne

-

Bayezid II Mosque in Istanbul (1500–1505)

-

Bayezid II Mosque in Istanbul: dome interiors

-

Bayezid II Hamam, part of the Bayezid II complex in Istanbul

Classical period

The start of the classical period is strongly associated with the works of Mimar Sinan.[95][96] During this period the bureaucracy of the Ottoman state, whose foundations were laid in Istanbul by Mehmet II, became increasingly elaborate and the profession of the architect became further institutionalized.[7] The long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent is also recognized as the apogee of Ottoman political and cultural development, with extensive patronage in art and architecture by the sultan, his family, and his high-ranking officials.[7] The master architect of the classical period, Mimar Sinan, served as the chief court architect (mimarbaşi) from 1538 until his death in 1588.[97] Sinan credited himself with the design of over 300 buildings,[98] though another estimate of his works puts it at nearly 500.[99] He is credited with designing buildings as far as Buda (present-day Budapest) and Mecca.[100] Sinan was probably not present to directly supervise projects far from the capital, so in these cases his designs were most likely executed by his assistants or by local architects.[101][102] In this period Ottoman architecture, especially under the work and influence of Sinan, saw a new unification and harmonization of the various architectural elements and influences that Ottoman architecture had previously absorbed but which had not yet been harmonized into a collective whole.[95] Ottoman architecture used a limited set of general forms – such as domes, semi-domes, and arcaded porticos – which were repeated in every structure and could be combined in a limited number of ways.[60] The ingenuity of successful architects such as Sinan lay in the careful and calculated attempts to solve problems of space, proportion, and harmony.[60] This period is also notable for the development of Iznik tile decoration in Ottoman monuments, with the artistic peak of this medium beginning in the second half of the 16th century.[103][104]

Earliest buildings of Suleiman's reign

Between the reigns of Bayezid II and Suleiman I, the reign of Selim I saw relatively little building activity. The Yavuz Selim Mosque complex in Istanbul, dedicated to Selim and containing his tomb, was completed after his death by Suleiman in 1522. It was quite possibly founded by Suleiman too, though the exact foundation date is not known.[105][92] The mosque is modelled on the Mosque of Bayezid II in Edirne, consisting of one large single-domed chamber.[106] The mosque is sometimes attributed to Sinan but it was not designed by him and the architect in charge is not known.[106][107][108] Other notable architectural complexes before Sinan's architect career, at the end of Selim I's reign or in Suleiman's early reign, are the Hafsa Sultan or Sultaniye Mosque in Manisa (circa 1522), the Fatih Pasha Mosque in Diyarbakir (completed in 1520 or 1523), and the Çoban Mustafa Pasha Complex in Gebze (1523–1524).[109][110]

Prior to being appointed chief court architect, Sinan was a military engineer who assisted the army on campaigns. His first major non-military project was the Hüsrev Pasha Mosque complex in Aleppo, one of the first major Ottoman monuments in that city. Its mosque and madrasa were completed in 1536–1537, though the completion of the overall complex is dated by an inscription to 1545, by which point Sinan had already moved on to Istanbul.[28] After his appointment to chief court architect in 1538, Sinan's first commission for Suleiman's family was the Haseki Hürrem Complex in Istanbul, dated to 1538–1539.[92][62] He also built the Tomb of Hayrettin Barbaros in the Beşiktaş neighbourhood in 1541.[111][112]

- Earliest buildings under Suleiman (before 1545)

-

Yavuz Selim I Mosque in Istanbul (1522), designed by unknown architect

-

Yavuz Selim I Mosque interior

-

Fatih Pasha Mosque in Diyarbakir (1520 or 1523)

-

Fatih Pasha Mosque interior, view of the dome

-

Çoban Mustafa Pasha Mosque in Gebze (1523–1524)

-

Hüsrev Pasha Mosque in Aleppo (1536–1537) (pictured before the recent damage of the Syrian civil war)

-

Haseki Hürrem Sultan Complex in Istanbul (1538–1539), designed by Sinan

-

Tomb of Hayreddin Barbaros in Beşiktaş (1541), designed by Sinan

The Şehzade Mosque and other early works of Sinan

Sinan's first major commission was the Şehzade Mosque complex, which Suleiman dedicated to Şehzade Mehmed, his son who died in 1543.[112] The mosque complex was built between 1545 and 1548.[92] Like all imperial külliyes, it included multiple buildings, of which the mosque was the most prominent element. The mosque has a rectangular floor plan divided into two equal squares, with one square occupied by the courtyard and the other occupied by the prayer hall. Two minarets stand on either side at the junction of these two squares.[92] The prayer hall consists of a central dome surrounded by semi-domes on four sides, with smaller domes occupying the corners. Smaller semi-domes also fill the space between the corner domes and the main semi-domes.

This design represents the culmination of the previous domed and semi-domed buildings in Ottoman architecture, bringing complete symmetry to the dome layout.[113] An early version of this design, on a smaller scale, had been used before Sinan as early as 1520 or 1523 in the Fatih Pasha Mosque in Diyarbakir.[114][115] While a cross-like layout had symbolic meaning in Christian architecture, in Ottoman architecture this was purely focused on heightening and emphasizing the central dome.[116] Sinan's early innovations are also evident in the way he organized the structural supports of the dome. Instead of having the dome rest on thick walls all around it (as was previously common), he concentrated the load-bearing supports into a limited number of buttresses along the outer walls of the mosque and in four pillars inside the mosque itself at the corners of the dome. This allowed for the walls in between the buttresses to be thinner, which in turn allowed for more windows to bring in more light.[117] Sinan also moved the outer walls inward, near the inner edge of the buttresses, so that the latter were less visible inside the mosque.[117] On the outside, he added domed porticos along the lateral façades of the building which further obscured the buttresses and gave the exterior a greater sense of monumentality.[117][118] Even the four pillars inside the mosque were given irregular shapes to give them a less heavy-handed appearance.[119]

The basic design of the Şehzade Mosque, with its symmetrical dome and four semi-dome layout, proved popular with later architects and was repeated in classical Ottoman mosques after Sinan (e.g. the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque, the New Mosque at Eminönü, and the 18th-century reconstruction of the Fatih Mosque).[120][121] It is even found in the 19th-century Muhammad Ali Mosque in Cairo.[122][123] Despite this legacy and the symmetry of its design, Sinan considered the Sehzade Mosque his "apprentice" work and was not satisfied with it.[92][124][125] During the rest of his career he did not repeat its layout in any of his other works. He instead experimented with other designs that seemed to aim for a completely unified interior space and for ways to emphasize the visitor's perception of the main dome upon entering a mosque. One of the results of this logic was that any space that did not belong the central domed space was reduced to a minimum, subordinate role, if not altogether absent.[126]

- Şehzade Mosque complex in Istanbul (1545–1548)

-

Şehzade Mosque: view of the exterior and one of the lateral porticos

-

Şehzade Mosque interior

-

Cemetery of the complex, including the Tomb of Şehzade Mehmed

Around the same time as the Şehzade Mosque construction Sinan also built the Mihrimah Sultan Mosque (also known as the Iskele Mosque) for one of Suleiman's daughters, Mihrimah Sultan. It was completed in 1547–1548 and is located in Üsküdar, across the Bosphorus.[127][128] It is notable for its wide "double porch", with an inner portico surrounded by an outer portico at the end of a sloped roof. This feature proved popular for certain patrons and was repeated by Sinan in several other mosques.[129] One example is the Rüstem Pasha Mosque in Tekirdağ (1552–1553).[130][131] Another example is the Sulaymaniyya Takiyya in Damascus, the western part of which (the mosque and a hospice) was built in 1554–1559.[132][133][134][135] This complex is also an important example of a Sinan-designed mosque far from Istanbul, and has local Syrian influences such as the use of ablaq masonry.[133] For Rüstem Pasha, Suleiman's grand vizier and son-in-law, Sinan also built the Rüstem Pasha Madrasa in Istanbul (1550), with an octagonal floor plan, and several caravanserais including the Rüstem Pasha Han in Galata (1550), the Rüstem Pasha Han in Ereğli (1552), the Rüstem Pasha Han in Edirne (1554), and the Taş Han in Erzurum (between 1544 and 1561).[136][137][138] In Istanbul Sinan also built the Haseki Hürrem Hamam near Hagia Sophia in 1556–1557, one of the most famous hammams he designed, which includes two equally-sized sections for men and women.[139][140][141] Between 1554 and 1564 he was also charged with upgrading the water supply system of the city, for which he built several impressive aqueducts in the Belgrad Forest and expanded on the older Byzantine water supply system.[142][143] One of Sinan's assistants, Hayruddin, was responsible for building the Stari Most, a single-span bridge in Mostar (present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina) that is considered one of the most impressive Ottoman monuments in the Balkans.[144] It was originally built between 1557 and 1566.[145][146]

- Other works of the early Sinan period

-

Mihrimah Sultan Mosque in Üsküdar (1547–1548)

-

Double porch in front of the Mihrimah Sultan Mosque

-

Rüstem Pasha Medrese in Istanbul (1550)

-

Mosque of the Sulaymaniyya Takiyya in Damascus (1554–1559)

-

Haseki Hürrem Hammam in Istanbul (1556–1557)

-

Güzelce Aqueduct near Istanbul (between 1554 and 1564)

The Süleymaniye complex and after

In 1550 Sinan began construction for the Süleymaniye complex, a monumental religious and charitable complex dedicated to Suleiman. Construction finished in 1557. Following the example of the earlier Fatih complex, it consists of many buildings arranged around the main mosque in the center, on a planned site occupying the summit of a hill in Istanbul. The buildings included the mosque itself, four general madrasas, a madrasa specialized for medicine, a madrasa specialized for hadiths (darülhadis), a mektep (Qur'anic school for children), a darüşşifa (hospital), a caravanserai, a tabhane (guesthouse), an imaret (public kitchen), a hammam, rows of shops, and a cemetery with two mausoleums.[147][148] In order to adapt the hilltop site, Sinan had to begin by laying solid foundations and retaining walls to form a wide terrace. The overall layout of buildings is less rigidly symmetrical than the Fatih complex, as Sinan opted to integrate it more flexibly into the existing urban fabric.[147] Thanks to its refined architecture, its scale, its dominant position on the city skyline, and its role as a symbol of Suleiman's powerful reign, the Süleymaniye Mosque complex is one of the most important symbols of Ottoman architecture and is often considered by scholars to be the most magnificent mosque in Istanbul.[149][150][22][151]

The mosque itself has a form similar to that of the earlier Bayezid II Mosque: a central dome preceded and followed by semi-domes, with smaller domes covering the sides. The reuse of an older mosque layout is something Sinan did not normally do. Doğan Kuban has suggested that it may have been due to a request from Suleiman.[152] In particular, the building replicates the central dome layout of the Hagia Sophia and this may be interpreted as a desire by Suleiman to emulate the structure of the Hagia Sophia, demonstrating how this ancient monument continued to hold tremendous symbolic power in Ottoman culture.[152] Nonetheless, Sinan employed innovations similar to those he used previously in the Şehzade Mosque: he concentrated the load-bearing supports into a limited number of columns and pillars, which allowed for more windows in the walls and minimized the physical separations within the interior of the prayer hall.[153][154] The exterior façades of the mosque are characterized by ground-level porticos, wide arches in which sets of windows are framed, and domes and semi-domes that progressively culminate upwards – in a roughly pyramidal fashion – to the large central dome.[153][155]

- Süleymaniye complex in Istanbul (1550–1557)

-

Süleymaniye Mosque courtyard

-

Süleymaniye Mosque interior

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Ottoman_architecture

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk