A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

In music theory, an interval is a difference in pitch between two sounds.[1] An interval may be described as horizontal, linear, or melodic if it refers to successively sounding tones, such as two adjacent pitches in a melody, and vertical or harmonic if it pertains to simultaneously sounding tones, such as in a chord.[2][3]

In Western music, intervals are most commonly differences between notes of a diatonic scale. Intervals between successive notes of a scale are also known as scale steps. The smallest of these intervals is a semitone. Intervals smaller than a semitone are called microtones. They can be formed using the notes of various kinds of non-diatonic scales. Some of the very smallest ones are called commas, and describe small discrepancies, observed in some tuning systems, between enharmonically equivalent notes such as C♯ and D♭. Intervals can be arbitrarily small, and even imperceptible to the human ear.

In physical terms, an interval is the ratio between two sonic frequencies. For example, any two notes an octave apart have a frequency ratio of 2:1. This means that successive increments of pitch by the same interval result in an exponential increase of frequency, even though the human ear perceives this as a linear increase in pitch. For this reason, intervals are often measured in cents, a unit derived from the logarithm of the frequency ratio.

In Western music theory, the most common naming scheme for intervals describes two properties of the interval: the quality (perfect, major, minor, augmented, diminished) and number (unison, second, third, etc.). Examples include the minor third or perfect fifth. These names identify not only the difference in semitones between the upper and lower notes but also how the interval is spelled. The importance of spelling stems from the historical practice of differentiating the frequency ratios of enharmonic intervals such as G–G♯ and G–A♭.[4]

Size

The size of an interval (also known as its width or height) can be represented using two alternative and equivalently valid methods, each appropriate to a different context: frequency ratios or cents.

Frequency ratios

The size of an interval between two notes may be measured by the ratio of their frequencies. When a musical instrument is tuned using a just intonation tuning system, the size of the main intervals can be expressed by small-integer ratios, such as 1:1 (unison), 2:1 (octave), 5:3 (major sixth), 3:2 (perfect fifth), 4:3 (perfect fourth), 5:4 (major third), 6:5 (minor third). Intervals with small-integer ratios are often called just intervals, or pure intervals.

Most commonly, however, musical instruments are nowadays tuned using a different tuning system, called 12-tone equal temperament. As a consequence, the size of most equal-tempered intervals cannot be expressed by small-integer ratios, although it is very close to the size of the corresponding just intervals. For instance, an equal-tempered fifth has a frequency ratio of 27⁄12:1, approximately equal to 1.498:1, or 2.997:2 (very close to 3:2). For a comparison between the size of intervals in different tuning systems, see § Size of intervals used in different tuning systems.

Cents

The standard system for comparing interval sizes is with cents. The cent is a logarithmic unit of measurement. If frequency is expressed in a logarithmic scale, and along that scale the distance between a given frequency and its double (also called octave) is divided into 1200 equal parts, each of these parts is one cent. In twelve-tone equal temperament (12-TET), a tuning system in which all semitones have the same size, the size of one semitone is exactly 100 cents. Hence, in 12-TET the cent can be also defined as one hundredth of a semitone.

Mathematically, the size in cents of the interval from frequency f1 to frequency f2 is

Main intervals

The table shows the most widely used conventional names for the intervals between the notes of a chromatic scale. A perfect unison (also known as perfect prime)[5] is an interval formed by two identical notes. Its size is zero cents. A semitone is any interval between two adjacent notes in a chromatic scale, a whole tone is an interval spanning two semitones (for example, a major second), and a tritone is an interval spanning three tones, or six semitones (for example, an augmented fourth).[a] Rarely, the term ditone is also used to indicate an interval spanning two whole tones (for example, a major third), or more strictly as a synonym of major third.

Intervals with different names may span the same number of semitones, and may even have the same width. For instance, the interval from D to F♯ is a major third, while that from D to G♭ is a diminished fourth. However, they both span 4 semitones. If the instrument is tuned so that the 12 notes of the chromatic scale are equally spaced (as in equal temperament), these intervals also have the same width. Namely, all semitones have a width of 100 cents, and all intervals spanning 4 semitones are 400 cents wide.

The names listed here cannot be determined by counting semitones alone. The rules to determine them are explained below. Other names, determined with different naming conventions, are listed in a separate section. Intervals smaller than one semitone (commas or microtones) and larger than one octave (compound intervals) are introduced below.

| Number of semitones |

Minor, major, or perfect intervals |

Short | Augmented or diminished intervals |

Short | Widely used alternative names |

Short | Audio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Perfect unison | P1 | Diminished second | d2 | |||

| 1 | Minor second | m2 | Augmented unison | A1 | Semitone, half tone, half step | S | |

| 2 | Major second | M2 | Diminished third | d3 | Tone, whole tone, whole step | T | |

| 3 | Minor third | m3 | Augmented second | A2 | |||

| 4 | Major third | M3 | Diminished fourth | d4 | |||

| 5 | Perfect fourth | P4 | Augmented third | A3 | |||

| 6 | Diminished fifth | d5 | Tritone | TT | |||

| Augmented fourth | A4 | ||||||

| 7 | Perfect fifth | P5 | Diminished sixth | d6 | |||

| 8 | Minor sixth | m6 | Augmented fifth | A5 | |||

| 9 | Major sixth | M6 | Diminished seventh | d7 | |||

| 10 | Minor seventh | m7 | Augmented sixth | A6 | |||

| 11 | Major seventh | M7 | Diminished octave | d8 | |||

| 12 | Perfect octave | P8 | Augmented seventh | A7 | |||

Interval number and qualityedit

In Western music theory, an interval is named according to its number (also called diatonic number, interval size[6] or generic interval[7]) and quality. For instance, major third (or M3) is an interval name, in which the term major (M) describes the quality of the interval, and third (3) indicates its number.

Numberedit

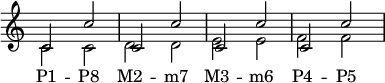

The number of an interval is the number of letter names or staff positions (lines and spaces) it encompasses, including the positions of both notes forming the interval. For instance, the interval C–G is a fifth (denoted P5) because the notes from C to the G above it encompass five letter names (C, D, E, F, G) and occupy five consecutive staff positions, including the positions of C and G. The table and the figure above show intervals with numbers ranging from 1 (e.g., P1) to 8 (e.g., P8). Intervals with larger numbers are called compound intervals.

There is a one-to-one correspondence between staff positions and diatonic-scale degrees (the notes of diatonic scale).[b] This means that interval numbers can also be determined by counting diatonic scale degrees, rather than staff positions, provided that the two notes that form the interval are drawn from a diatonic scale. Namely, C–G is a fifth because in any diatonic scale that contains C and G, the sequence from C to G includes five notes. For instance, in the A♭-major diatonic scale, the five notes are C–D♭–E♭–F–G (see figure). This is not true for all kinds of scales. For instance, in a chromatic scale, there are eight notes from C to G: (C–C♯–D–D♯–E–F–F♯–G). This is the reason interval numbers are also called diatonic numbers, and this convention is called diatonic numbering.

If one adds any accidentals to the notes that form an interval, by definition the notes do not change their staff positions. As a consequence, any interval has the same interval number as the corresponding natural interval, formed by the same notes without accidentals. For instance, the intervals C–G♯ (spanning 8 semitones) and C♯–G (spanning 6 semitones) are fifths, like the corresponding natural interval C–G (7 semitones).

Notice that interval numbers represent an inclusive count of encompassed staff positions or note names, not the difference between the endpoints. In other words, one starts counting the lower pitch as one, not zero. For that reason, the interval C–C, a perfect unison, is called a prime (meaning "1"), even though there is no difference between the endpoints. Continuing, the interval C–D is a second, but D is only one staff position, or diatonic-scale degree, above C. Similarly, C–E is a third, but E is only two staff positions above C, and so on. As a consequence, joining two intervals always yields an interval number one less than their sum. For instance, the intervals C–E and E–G are thirds, but joined together they form a fifth (C–G), not a sixth. Similarly, a stack of three thirds, such as C–E, E–G, and G–B, is a seventh (C–B), not a ninth.

This scheme applies to intervals up to an octave (12 semitones). For larger intervals, see § Compound intervals below.

Quality edit

The name of any interval is further qualified using the terms perfect (P), major (M), minor (m), augmented (A), and diminished (d). This is called its interval quality (or modifier[8][7]). It is possible to have doubly diminished and doubly augmented intervals, but these are quite rare, as they occur only in chromatic contexts. The combination of number (or generic interval) and quality (or modifier) is called the specific interval,[7] diatonic interval (sometimes used only for intervals appearing in the diatonic scale), or simply interval.[8]

The quality of a compound interval is the quality of the simple interval on which it is based. Some other qualifiers like neutral, subminor, and supermajor are used for non-diatonic intervals.

Perfectedit

Perfect intervals are so-called because they were traditionally considered perfectly consonant,[9] although in Western classical music the perfect fourth was sometimes regarded as a less than perfect consonance, when its function was contrapuntal.[vague] Conversely, minor, major, augmented, or diminished intervals are typically considered less consonant, and were traditionally classified as mediocre consonances, imperfect consonances, or near-dissonances.[9]

Within a diatonic scale[b] all unisons (P1) and octaves (P8) are perfect. Most fourths and fifths are also perfect (P4 and P5), with five and seven semitones respectively. One occurrence of a fourth is augmented (A4) and one fifth is diminished (d5), both spanning six semitones. For instance, in a C-major scale, the A4 is between F and B, and the d5 is between B and F (see table).

By definition, the inversion of a perfect interval is also perfect. Since the inversion does not change the pitch class of the two notes, it hardly affects their level of consonance (matching of their harmonics). Conversely, other kinds of intervals have the opposite quality with respect to their inversion. The inversion of a major interval is a minor interval, the inversion of an augmented interval is a diminished interval.

Major and minoredit

As shown in the table, a diatonic scale[b] defines seven intervals for each interval number, each starting from a different note (seven unisons, seven seconds, etc.). The intervals formed by the notes of a diatonic scale are called diatonic. Except for unisons and octaves, the diatonic intervals with a given interval number always occur in two sizes, which differ by one semitone. For example, six of the fifths span seven semitones. The other one spans six semitones. Four of the thirds span three semitones, the others four. If one of the two versions is a perfect interval, the other is called either diminished (i.e. narrowed by one semitone) or augmented (i.e. widened by one semitone). Otherwise, the larger version is called major, the smaller one minor. For instance, since a 7-semitone fifth is a perfect interval (P5), the 6-semitone fifth is called "diminished fifth" (d5). Conversely, since neither kind of third is perfect, the larger one is called "major third" (M3), the smaller one "minor third" (m3).

Within a diatonic scale,[b] unisons and octaves are always qualified as perfect, fourths as either perfect or augmented, fifths as perfect or diminished, and all the other intervals (seconds, thirds, sixths, sevenths) as major or minor.

Augmented and diminishededit

Augmented intervals are wider by one semitone than perfect or major intervals, while having the same interval number (i.e., encompassing the same number of staff positions): they are wider by a chromatic semitone. Diminished intervals, on the other hand, are narrower by one semitone than perfect or minor intervals of the same interval number: they are narrower by a chromatic semitone. For instance, an augmented third such as C–E♯ spans five semitones, exceeding a major third (C–E) by one semitone, while a diminished third such as C♯–E♭ spans two semitones, falling short of a minor third (C–E♭) by one semitone.

The augmented fourth (A4) and the diminished fifth (d5) are the only augmented and diminished intervals that appear in diatonic scales[b] (see table).

Exampleedit

Neither the number, nor the quality of an interval can be determined by counting semitones alone. As explained above, the number of staff positions must be taken into account as well.

For example, as shown in the table below, there are four semitones between A♭ and B♯, between A and C♯, between A and D♭, and between A♯ and E![]() , but

, but

- A♭–B♯ is a second, as it encompasses two staff positions (A, B), and it is doubly augmented, as it exceeds a major second (such as A–B) by two semitones.

- A–C♯ is a third, as it encompasses three staff positions (A, B, C), and it is major, as it spans 4 semitones.

- A–D♭ is a fourth, as it encompasses four staff positions (A, B, C, D), and it is diminished, as it falls short of a perfect fourth (such as A–D) by one semitone.

- A♯-E

is a fifth, as it encompasses five staff positions (A, B, C, D, E), and it is triply diminished, as it falls short of a perfect fifth (such as A–E) by three semitones.

is a fifth, as it encompasses five staff positions (A, B, C, D, E), and it is triply diminished, as it falls short of a perfect fifth (such as A–E) by three semitones.

| Number of semitones |

Interval name | Staff positions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 4 | doubly augmented second (AA2) | A♭ | B♯ | |||

| 4 | major third (M3) | A | C♯ | |||

| 4 | diminished fourth (d4) | A | D♭ | |||

| 4 | triply diminished fifth (ddd5) | A♯ | E | |||

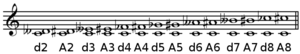

Shorthand notationedit

Intervals are often abbreviated with a P for perfect, m for minor, M for major, d for diminished, A for augmented, followed by the interval number. The indications M and P are often omitted. The octave is P8, and a unison is usually referred to simply as "a unison" but can be labeled P1. The tritone, an augmented fourth or diminished fifth is often TT. The interval qualities may be also abbreviated with perf, min, maj, dim, aug. Examples:

- m2 (or min2): minor second,

- M3 (or maj3): major third,

- A4 (or aug4): augmented fourth,

- d5 (or dim5): diminished fifth,

- P5 (or perf5): perfect fifth.

Inversionedit

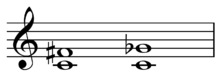

A simple interval (i.e., an interval smaller than or equal to an octave) may be inverted by raising the lower pitch an octave or lowering the upper pitch an octave. For example, the fourth from a lower C to a higher F may be inverted to make a fifth, from a lower F to a higher C.

There are two rules to determine the number and quality of the inversion of any simple interval:[10]

- The interval number and the number of its inversion always add up to nine (4 + 5 = 9, in the example just given).

- The inversion of a major interval is a minor interval, and vice versa; the inversion of a perfect interval is also perfect; the inversion of an augmented interval is a diminished interval, and vice versa; the inversion of a doubly augmented interval is a doubly diminished interval, and vice versa.

For example, the interval from C to the E♭ above it is a minor third. By the two rules just given, the interval from E♭ to the C above it must be a major sixth.

Since compound intervals are larger than an octave, "the inversion of any compound interval is always the same as the inversion of the simple interval from which it is compounded".[11]

For intervals identified by their ratio, the inversion is determined by reversing the ratio and multiplying the ratio by 2 until it is greater than 1. For example, the inversion of a 5:4 ratio is an 8:5 ratio.

For intervals identified by an integer number of semitones, the inversion is obtained by subtracting that number from 12.

Since an interval class is the lower number selected among the interval integer and its inversion, interval classes cannot be inverted.

Classificationedit

Intervals can be described, classified, or compared with each other according to various criteria.

Melodic and harmonicedit

An interval can be described as

- Vertical or harmonic if the two notes sound simultaneously

- Horizontal, linear, or melodic if they sound successively.[2] Melodic intervals can be ascending (lower pitch precedes higher pitch) or descending.

Diatonic and chromaticedit

In general,

- A diatonic interval is an interval formed by two notes of a diatonic scale.

- A chromatic interval is a non-diatonic interval formed by two notes of a chromatic scale.

The table above depicts the 56 diatonic intervals formed by the notes of the C major scale (a diatonic scale). Notice that these intervals, as well as any other diatonic interval, can be also formed by the notes of a chromatic scale.

The distinction between diatonic and chromatic intervals is controversial, as it is based on the definition of diatonic scale, which is variable in the literature. For example, the interval B–E♭ (a diminished fourth, occurring in the harmonic C-minor scale) is considered diatonic if the harmonic minor scales are considered diatonic as well.[12] Otherwise, it is considered chromatic. For further details, see the main article.

By a commonly used definition of diatonic scale[b] (which excludes the harmonic minor and melodic minor scales), all perfect, major and minor intervals are diatonic. Conversely, no augmented or diminished interval is diatonic, except for the augmented fourth and diminished fifth.

The distinction between diatonic and chromatic intervals may be also sensitive to context. The above-mentioned 56 intervals formed by the C-major scale are sometimes called diatonic to C major. All other intervals are called chromatic to C major. For instance, the perfect fifth A♭–E♭ is chromatic to C major, because A♭ and E♭ are not contained in the C major scale. However, it is diatonic to others, such as the A♭ major scale.

Consonant and dissonantedit

Consonance and dissonance are relative terms that refer to the stability, or state of repose, of particular musical effects. Dissonant intervals are those that cause tension and desire to be resolved to consonant intervals.

These terms are relative to the usage of different compositional styles.

- In 15th- and 16th-century usage, perfect fifths and octaves, and major and minor thirds and sixths were considered harmonically consonant, and all other intervals dissonant, including the perfect fourth, which by 1473 was described (by Johannes Tinctoris) as dissonant, except between the upper parts of a vertical sonority—for example, with a supporting third below ("6-3 chords").[13] In the common practice period, it makes more sense to speak of consonant and dissonant chords, and certain intervals previously considered dissonant (such as minor sevenths) became acceptable in certain contexts. However, 16th-century practice was still taught to beginning musicians throughout this period.

- Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894) theorised that dissonance was caused by the presence of beats.[14] Helmholtz further believed that the beating produced by the upper partials of harmonic sounds was the cause of dissonance for intervals too far apart to produce beating between the fundamentals.[15] Helmholtz then designated that two harmonic tones that shared common low partials would be more consonant, as they produced less beats.[16][17] Helmholtz disregarded partials above the seventh, as he believed that they were not audible enough to have significant effect.[18] From this Helmholtz categorises the octave, perfect fifth, perfect fourth, major sixth, major third, and minor third as consonant, in decreasing value, and other intervals as dissonant.

- David Cope (1997) suggests the concept of interval strength,[19] in which an interval's strength, consonance, or stability is determined by its approximation to a lower and stronger, or higher and weaker, position in the harmonic series. See also: Lipps–Meyer law and #Interval root

All of the above analyses refer to vertical (simultaneous) intervals.

Simple and compoundedit

A simple interval is an interval spanning at most one octave (see Main intervals above). Intervals spanning more than one octave are called compound intervals, as they can be obtained by adding one or more octaves to a simple interval (see below for details).[20]

Steps and skipsedit

Linear (melodic) intervals may be described as steps or skips. A step, or conjunct motion,[21] is a linear interval between two consecutive notes of a scale. Any larger interval is called a skip (also called a leap), or disjunct motion.[21] In the diatonic scale,[b] a step is either a minor second (sometimes also called half step) or major second (sometimes also called whole step), with all intervals of a minor third or larger being skips.

For example, C to D (major second) is a step, whereas C to E (major third) is a skip.

More generally, a step is a smaller or narrower interval in a musical line, and a skip is a wider or larger interval, where the categorization of intervals into steps and skips is determined by the tuning system and the pitch space used.

Melodic motion in which the interval between any two consecutive pitches is no more than a step, or, less strictly, where skips are rare, is called stepwise or conjunct melodic motion, as opposed to skipwise or disjunct melodic motions, characterized by frequent skips.

Enharmonic intervalsedit

Two intervals are considered enharmonic, or enharmonically equivalent, if they both contain the same pitches spelled in different ways; that is, if the notes in the two intervals are themselves enharmonically equivalent. Enharmonic intervals span the same number of semitones.

For example, the four intervals listed in the table below are all enharmonically equivalent, because the notes F♯ and G♭ indicate the same pitch, and the same is true for A♯ and B♭. All these intervals span four semitones.

| Number of semitones |

Interval name | Staff positions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 4 | major third | F♯ | A♯ | ||

| 4 | major third | G♭ | B♭ | ||

| 4 | diminished fourth | F♯ | B♭ | ||

| 4 | doubly augmented second | G♭ | A♯ | ||

When played as isolated chords on a piano keyboard, these intervals are indistinguishable to the ear, because they are all played with the same two keys. However, in a musical context, the diatonic function of the notes these intervals incorporate is very different.

The discussion above assumes the use of the prevalent tuning system, 12-tone equal temperament ("12-TET"). But in other historic meantone temperaments, the pitches of pairs of notes such as F♯ and G♭ may not necessarily coincide. These two notes are enharmonic in 12-TET, but may not be so in another tuning system. In such cases, the intervals they form would also not be enharmonic. For example, in quarter-comma meantone, all four intervals shown in the example above would be different.

Minute intervalsedit

There are also a number of minute intervals not found in the chromatic scale or labeled with a diatonic function, which have names of their own. They may be described as microtones, and some of them can be also classified as commas, as they describe small discrepancies, observed in some tuning systems, between enharmonically equivalent notes. In the following list, the interval sizes in cents are approximate.

- A Pythagorean comma is the difference between twelve justly tuned perfect fifths and seven octaves. It is expressed by the frequency ratio 531441:524288 (23.5 cents).

- A syntonic comma is the difference between four justly tuned perfect fifths and two octaves plus a major third. It is expressed by the ratio 81:80 (21.5 cents).

- A septimal comma is 64:63 (27.3 cents), and is the difference between the Pythagorean or 3-limit "7th" and the "harmonic 7th". Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Interval_(music)

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk