A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article may have confusing or ambiguous abbreviations. (November 2023) |

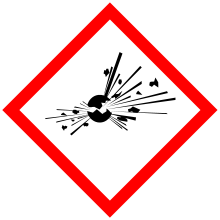

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An explosive charge is a measured quantity of explosive material, which may either be composed solely of one ingredient or be a mixture containing at least two substances.

The potential energy stored in an explosive material may, for example, be

- chemical energy, such as nitroglycerin or grain dust

- pressurized gas, such as a gas cylinder, aerosol can, or BLEVE

- nuclear energy, such as in the fissile isotopes uranium-235 and plutonium-239

Explosive materials may be categorized by the speed at which they expand. Materials that detonate (the front of the chemical reaction moves faster through the material than the speed of sound) are said to be "high explosives" and materials that deflagrate are said to be "low explosives". Explosives may also be categorized by their sensitivity. Sensitive materials that can be initiated by a relatively small amount of heat or pressure are primary explosives and materials that are relatively insensitive are secondary or tertiary explosives.

A wide variety of chemicals can explode; a smaller number are manufactured specifically for the purpose of being used as explosives. The remainder are too dangerous, sensitive, toxic, expensive, unstable, or prone to decomposition or degradation over short time spans.

In contrast, some materials are merely combustible or flammable if they burn without exploding.

The distinction, however, is not razor-sharp. Certain materials—dusts, powders, gases, or volatile organic liquids—may be simply combustible or flammable under ordinary conditions, but become explosive in specific situations or forms, such as dispersed airborne clouds, or confinement or sudden release.

History

Early thermal weapons, such as Greek fire, have existed since ancient times. At its roots, the history of chemical explosives lies in the history of gunpowder.[1][2] During the Tang dynasty in the 9th century, Taoist Chinese alchemists were eagerly trying to find the elixir of immortality.[3] In the process, they stumbled upon the explosive invention of black powder made from coal, saltpeter, and sulfur in 1044. Gunpowder was the first form of chemical explosives and by 1161, the Chinese were using explosives for the first time in warfare.[4][5][6] The Chinese would incorporate explosives fired from bamboo or bronze tubes known as bamboo firecrackers. The Chinese also inserted live rats inside the bamboo firecrackers; when fired toward the enemy, the flaming rats created great psychological ramifications—scaring enemy soldiers away and causing cavalry units to go wild.[7]

The first useful explosive stronger than black powder was nitroglycerin, developed in 1847. Since nitroglycerin is a liquid and highly unstable, it was replaced by nitrocellulose, trinitrotoluene (TNT) in 1863, smokeless powder, dynamite in 1867 and gelignite (the latter two being sophisticated stabilized preparations of nitroglycerin rather than chemical alternatives, both invented by Alfred Nobel). World War I saw the adoption of TNT in artillery shells. World War II saw extensive use of new explosives (see List of explosives used during World War II).

In turn, these have largely been replaced by more powerful explosives such as C-4 and PETN. However, C-4 and PETN react with metal and catch fire easily, yet unlike TNT, C-4 and PETN are waterproof and malleable.[8]

Applications

Commercial

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2024) |

The largest commercial application of explosives is mining. Whether the mine is on the surface or is buried underground, the detonation or deflagration of either a high or low explosive in a confined space can be used to liberate a fairly specific sub-volume of a brittle material (rock) in a much larger volume of the same or similar material. The mining industry tends to use nitrate-based explosives such as emulsions of fuel oil and ammonium nitrate solutions,[9] mixtures of ammonium nitrate prills (fertilizer pellets) and fuel oil (ANFO) and gelatinous suspensions or slurries[10] of ammonium nitrate and combustible fuels.

In materials science and engineering, explosives are used in cladding (explosion welding). A thin plate of some material is placed atop a thick layer of a different material, both layers typically of metal. Atop the thin layer is placed an explosive. At one end of the layer of explosive, the explosion is initiated. The two metallic layers are forced together at high speed and with great force. The explosion spreads from the initiation site throughout the explosive. Ideally, this produces a metallurgical bond between the two layers.

As the length of time the shock wave spends at any point is small, we can see mixing of the two metals and their surface chemistries, through some fraction of the depth, and they tend to be mixed in some way. It is possible that some fraction of the surface material from either layer eventually gets ejected when the end of material is reached. Hence, the mass of the now "welded" bilayer, may be less than the sum of the masses of the two initial layers.

There are applications[which?] where a shock wave, and electrostatics, can result in high velocity projectiles.

Military

Civilian

Safety

Types

Chemical

An explosion is a type of spontaneous chemical reaction that, once initiated, is driven by both a large exothermic change (great release of heat) and a large positive entropy change (great quantities of gases are released) in going from reactants to products, thereby constituting a thermodynamically favorable process in addition to one that propagates very rapidly. Thus, explosives are substances that contain a large amount of energy stored in chemical bonds. The energetic stability of the gaseous products and hence their generation comes from the formation of strongly bonded species like carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and (di)nitrogen, which contain strong double and triple bonds having bond strengths of nearly 1 MJ/mole. Consequently, most commercial explosives are organic compounds containing –NO2, –ONO2 and –NHNO2 groups that, when detonated, release gases like the aforementioned (e.g., nitroglycerin, TNT, HMX, PETN, nitrocellulose).[11]

An explosive is classified as a low or high explosive according to its rate of combustion: low explosives burn rapidly (or deflagrate), while high explosives detonate. While these definitions are distinct, the problem of precisely measuring rapid decomposition makes practical classification of explosives difficult. The speed of sound at sea level (343 m/sec) is generally accepted as the distinction between low explosive and high explosive.

Traditional explosives mechanics is based on the shock-sensitive rapid oxidation of carbon and hydrogen to carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and water in the form of steam. Nitrates typically provide the required oxygen to burn the carbon and hydrogen fuel. High explosives tend to have the oxygen, carbon and hydrogen contained in one organic molecule, and less sensitive explosives like ANFO are combinations of fuel (carbon and hydrogen fuel oil) and ammonium nitrate. A sensitizer such as powdered aluminum may be added to an explosive to increase the energy of the detonation. Once detonated, the nitrogen portion of the explosive formulation emerges as nitrogen gas and toxic nitric oxides.

Decomposition

The chemical decomposition of an explosive may take years, days, hours, or a fraction of a second. The slower processes of decomposition take place in storage and are of interest only from a stability standpoint. Of more interest are the other two rapid forms besides decomposition: deflagration and detonation.

Deflagration

In deflagration, decomposition of the explosive material is propagated by a flame front which moves slowly through the explosive material at speeds less than the speed of sound within the substance (which is usually higher than 340 m/s or 1240 km/h in most liquid or solid materials)[12] in contrast to detonation, which occurs at speeds greater than the speed of sound. Deflagration is a characteristic of low explosive material.

Detonation

This term is used to describe an explosive phenomenon whereby the decomposition is propagated by a shock wave traversing the explosive material at speeds greater than the speed of sound within the substance.[13] The shock front is capable of passing through the high explosive material at supersonic speeds, typically thousands of metres per second.

Exotic

In addition to chemical explosives, there are a number of more exotic explosive materials, and exotic methods of causing explosions. Examples include nuclear explosives, and abruptly heating a substance to a plasma state with a high-intensity laser or electric arc.

Laser- and arc-heating are used in laser detonators, exploding-bridgewire detonators, and exploding foil initiators, where a shock wave and then detonation in conventional chemical explosive material is created by laser- or electric-arc heating. Laser and electric energy are not currently used in practice to generate most of the required energy, but only to initiate reactions.

Properties

To determine the suitability of an explosive substance for a particular use, its physical properties must first be known. The usefulness of an explosive can only be appreciated when the properties and the factors affecting them are fully understood. Some of the more important characteristics are listed below:

Sensitivity

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=High-explosiveText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk