A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

French Algeria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1830–1962 | |||||||||||||||

| Anthem: La Parisienne (1830–1848) Le Chant des Girondins (1848–1852) Partant pour la Syrie (1852–1870) La Marseillaise (1870–1962) | |||||||||||||||

Official Arabic seal of the Governor General of Algeria | |||||||||||||||

Chronological map of French Algeria's evolution | |||||||||||||||

| Status | 1830–1848: French colony 1848–1962: Part of France | ||||||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Algiers | ||||||||||||||

| Official languages | French | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||

| Government | French Department | ||||||||||||||

| Governor General | |||||||||||||||

• 1830 (first) | Louis-Auguste-Victor Bourmont | ||||||||||||||

• 1962 (last) | Christian Fouchet | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Algerian Assembly (1948–1956) | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

| 5 July 1830 | |||||||||||||||

| 5 July 1962 | |||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

• Total | 2,381,741 km2 (919,595 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Budju (1830–1848) (Algerian) Franc (1848–1962) | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

French Algeria (French: Alger until 1839, then Algérie afterwards;[1] unofficially Algérie française,[2][3] Arabic: الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of Algerian history when the country was a colony and later an integral part of France.

French rule in the region began in 1830, after the successful French invasion of Algeria, and lasted until the end of the Algerian War in the mid 20th century, by which Algeria gained independence in 1962. After being a French colony from 1830 to 1848, Algeria was designated as a department, or part of France from 4 November 1848, when the Constitution of French Second Republic took effect, until its independence on 5 July 1962.

As a recognized jurisdiction of France, Algeria became a destination for hundreds of thousands of European immigrants. They were first known as colons, and later as pieds-noirs, a term applying especially to ethnic Europeans born there. The indigenous Muslim population comprised the majority of the territory throughout its history. It is estimated that the native Algerian population fell by up to one-third between 1830 and 1875 due to warfare, disease and starvation.[4] Gradually, dissatisfaction among the Muslim population, due to their lack of political and economic freedom, fueled calls for greater political autonomy, and eventually independence from France.[5] Tensions between the two groups came to a head in 1954, when the first violent events began of what was later called the Algerian War. It was characterised by guerrilla warfare and crimes against humanity used by the French in order to stop the revolt. The war ended in 1962, when Algeria gained independence following the Evian agreements in March 1962 and the self-determination referendum in July 1962.

During its last years as part of France, Algeria was a founding member of the European Coal and Steel Community and the European Economic Community.[6]

History

Initial conflicts

Since the capture of Algiers in 1516 by the Ottoman admirals, brothers Ours and Hayreddin Barbarossa, Algeria had been a base for conflict and piracy in the Mediterranean basin. In 1681, Louis XIV asked Admiral Abraham Duquesne to fight the Berber pirates. He also ordered a large-scale attack on Algiers between 1682 and 1683 on the pretext of assisting and rescuing enslaved Christians, usually Europeans taken as captives in raids.[7] Again, Jean II d'Estrées bombarded Tripoli and Algiers from 1685 to 1688. An ambassador from Algiers visited the Court in Versailles, and a treaty was signed in 1690 that provided peace throughout the 18th century.[8]

During the Directory regime of the First French Republic (1795–99), the Bacri and the Busnach, Jewish merchants of Algiers, provided large quantities of grain for Napoleon's soldiers who participated in the Italian campaign of 1796. But Bonaparte refused to pay the bill, claiming it was excessive. In 1820, Louis XVIII paid back half of the Directory's debts. The Dey, who had loaned the Bacri 250,000 francs, requested the rest of the money from France.

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

The Dey of Algiers was weak politically, economically, and militarily. Algeria was then part of the Barbary States, along with today's Tunisia; these depended on the Ottoman Empire, then led by Mahmud II but enjoyed relative independence. The Barbary Coast was the stronghold of Berber pirates, who carried out raids against European and United States ships. Conflicts between the Barbary States and the newly independent United States of America culminated in the First (1801–05) and Second (1815) Barbary Wars. An Anglo-Dutch force, led by Admiral Lord Exmouth, carried out a punitive expedition, the August 1816 bombardment of Algiers. The Dey was forced to sign the Barbary treaties, because the technological advantage of U.S., British, and French forces overwhelmed the Algerians' expertise at naval warfare.[citation needed]

Following the conquest under the July monarchy, France referred to the Algerian territories as "French possessions in North Africa". This was disputed by the Ottoman Empire, which had not given up its claim. In 1839 Marshal General Jean-de-Dieu Soult, Duke of Dalmatia, first named these territories as "Algeria". [9]

French conquest of Algeria

The invasion of Algeria against the Regency of Algiers (Ottoman Algeria) was initiated in the last days of the Bourbon Restoration by Charles X, as an attempt to increase his popularity amongst the French people.[10] He particularly hoped to appeal to the many veterans of the Napoleonic Wars who lived in Paris. His intention was to bolster patriotic sentiment, and distract attention from ineptly handled domestic policies by "skirmishing against the dey."[11][12][13]

Fly Whisk Incident (April 1827)

In the 1790s, France had contracted to purchase wheat for the French army from two merchants in Algiers, Messrs. Bacri and Boushnak, and was in arrears paying them. Bacri and Boushnak owed money to the dey and claimed they could not pay it until France paid its debts to them. The dey had unsuccessfully negotiated with Pierre Deval, the French consul, to rectify this situation, and he suspected Deval of collaborating with the merchants against him, especially when the French government made no provisions in 1820 to pay the merchants. Deval's nephew Alexandre, the consul in Bône, further angered the dey by fortifying French storehouses in Bône and La Calle, contrary to the terms of prior agreements.[14]

After a contentious meeting in which Deval refused to provide satisfactory answers on 29 April 1827, the dey struck Deval with his fly whisk. Charles X used this slight against his diplomatic representative to first demand an apology from the dey, and then to initiate a blockade against the port of Algiers. France demanded that the dey send an ambassador to France to resolve the incident. When the dey responded with cannon fire directed toward one of the blockading ships, the French determined that more forceful action was required.[15]

Invasion of Algiers (June 1830)

Pierre Deval and other French residents of Algiers left for France, while the Minister of War, Clermont-Tonnerre, proposed a military expedition. However, the Count of Villèle, an ultra-royalist, President of the council and the monarch's heir, opposed any military action. The Bourbon Restoration government finally decided to blockade Algiers for three years. Meanwhile, the Berber pirates were able to exploit the geography of the coast with ease. Before the failure of the blockade, the Restoration decided on 31 January 1830 to engage a military expedition against Algiers.

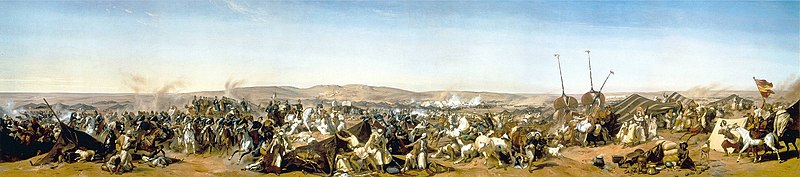

Admiral Duperré commanded an armada of 600 ships that originated from Toulon, leading it to Algiers. Using Napoleon's 1808 contingency plan for the invasion of Algeria, General de Bourmont then landed 27 kilometres (17 mi) west of Algiers, at Sidi Ferruch on 14 June 1830, with 34,000 soldiers. In response to the French, the Algerian dey ordered an opposition consisting of 7,000 janissaries, 19,000 troops from the beys of Constantine and Oran, and about 17,000 Kabyles. The French established a strong beachhead and pushed toward Algiers, thanks in part to superior artillery and better organization. The French troops took the advantage on 19 June during the battle of Staouéli, and entered Algiers on 5 July after a three-week campaign. The dey agreed to surrender in exchange for his freedom and the offer to retain possession of his personal wealth. Five days later, he exiled himself with his family, departing on a French ship for the Italian peninsula. 2,500 janissaries also quit the Algerian territories, heading for Asia,[clarification needed] on 11 July. The French army then recruited the first zouaves (a title given to certain light infantry regiments) in October, followed by the spahis regiments, while France expropriated all the land properties belonging to the Turkish settlers, known as Beliks. In the western region of Oran, Sultan Abderrahmane of Morocco, the Commander of the Faithful, could not remain indifferent to the massacres committed by the French Christian troops and to belligerent calls for jihad from the marabouts. Despite the diplomatic rupture between Morocco and the Two Sicilies in 1830, and the naval warfare engaged against the Austrian Empire as well as with Spain, then headed by Ferdinand VII, Sultan Abderrahmane lent his support to the Algerian insurgency of Abd El-Kader. The latter fought for years against the French. Directing an army of 12,000 men, Abd El-Kader first organized the blockade of Oran.

Algerian refugees were welcomed by the Moroccan population, while the Sultan recommended that the authorities of Tetuan assist them, by providing jobs in the administration or the military forces. The inhabitants of Tlemcen, near the Moroccan border, asked that they be placed under the Sultan's authority in order to escape the invaders. Abderrahmane named his nephew Prince Moulay Ali Caliph of Tlemcen, charged with the protection of the city. In retaliation France executed two Moroccans: Mohamed Beliano and Benkirane, as spies, while their goods were seized by the military governor of Oran, Pierre François Xavier Boyer.

Hardly had the news of the capture of Algiers reached Paris than Charles X was deposed during the Three Glorious Days of July 1830, and his cousin Louis-Philippe, the "citizen king ," was named to preside over a constitutional monarchy. The new government, composed of liberal opponents of the Algiers expedition, was reluctant to pursue the conquest begun by the old regime, but withdrawing from Algeria proved more difficult than conquering it.[citation needed]

Alexis de Tocqueville's views on Algeria were instrumental in its brutal and formal colonization. He advocated for a mixed system of "total domination and total colonization" whereby French military would wage total war against civilian populations while a colonial administration would provide rule of law and property rights to settlers within French occupied cities.[16][17]

Characterization as genocide

Some governments and scholars have called France's conquest of Algeria a genocide.[18]

For example, Ben Kiernan, an Australian expert on Cambodian genocide[19] wrote in Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur on the French conquest of Algeria:[20]

By 1875, the French conquest was complete. The war had killed approximately 825,000 indigenous Algerians since 1830. A long shadow of genocidal hatred persisted, provoking a French author to protest in 1882 that in Algeria, "we hear it repeated every day that we must expel the native and, if necessary, destroy him." As a French statistical journal urged five years later, "the system of extermination must give way to a policy of penetration."

—Ben Kiernan, Blood and Soil

When France recognized the Armenian genocide, Turkey accused France of having committed genocide against 15% of Algeria's population.[21][22]

Popular revolts against the French occupation

Conquest of the Algerian territories under the July Monarchy (1830–1848)

On 1 December 1830, King Louis-Philippe named the Duc de Rovigo as head of military staff in Algeria. De Rovigo took control of Bône and initiated colonisation of the land. He was recalled in 1833 due to the overtly violent nature of the repression. Wishing to avoid a conflict with Morocco, Louis-Philippe sent an extraordinary mission to the sultan, mixed with displays of military might, sending war ships to the Bay of Tangier. An ambassador was sent to Sultan Moulay Abderrahmane in February 1832, headed by the Count Charles-Edgar de Mornay and including the painter Eugène Delacroix. However the sultan refused French demands that he evacuate Tlemcen.

In 1834, France annexed as a colony the occupied areas of Algeria, which had an estimated Muslim population of about two million. Colonial administration in the occupied areas — the so-called régime du sabre (government of the sword) — was placed under a governor-general, a high-ranking army officer invested with civil and military jurisdiction, who was responsible to the minister of war. Marshal Bugeaud, who became the first governor-general, headed the conquest.

Soon after the conquest of Algiers, the soldier-politician Bertrand Clauzel and others formed a company to acquire agricultural land and, despite official discouragement, to subsidize its settlement by European farmers, triggering a land rush. Clauzel recognized the farming potential of the Mitidja Plain and envisioned the large-scale production there of cotton. As governor-general (1835–36), he used his office to make private investments in land and encouraged army officers and bureaucrats in his administration to do the same. This development created a vested interest among government officials in greater French involvement in Algeria. Commercial interests with influence in the government also began to recognize the prospects for profitable land speculation in expanding the French zone of occupation. They created large agricultural tracts, built factories and businesses, and hired local labor.

Among others testimonies, Lieutenant-colonel Lucien de Montagnac wrote on 15 March 1843, in a letter to a friend:

All populations who do not accept our conditions must be despoiled. Everything must be seized, devastated, without age or sex distinction: grass must not grow any more where the French army has set foot. Who wants the end wants the means, whatever may say our philanthropists. I personally warn all good soldiers whom I have the honour to lead that if they happen to bring me a living Arab, they will receive a beating with the flat of the saber.... This is how, my dear friend, we must make war against Arabs: kill all men over the age of fifteen, take all their women and children, load them onto naval vessels, send them to the Marquesas Islands or elsewhere. In one word, annihilate everything that will not crawl beneath our feet like dogs.[23]

Whatever initial misgivings Louis Philippe's government may have had about occupying Algeria, the geopolitical realities of the situation created by the 1830 intervention argued strongly for reinforcing French presence there. France had reason for concern that Britain, which was pledged to maintain the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire, would move to fill the vacuum left by a French withdrawal. The French devised elaborate plans for settling the hinterland left by Ottoman provincial authorities in 1830, but their efforts at state-building were unsuccessful on account of lengthy armed resistance.

The most successful local opposition immediately after the fall of Algiers was led by Ahmad ibn Muhammad, bey of Constantine. He initiated a radical overhaul of the Ottoman administration in his beylik by replacing Turkish officials with local leaders, making Arabic the official language, and attempting to reform finances according to the precepts of Islam. After the French failed in several attempts to gain some of the bey's territories through negotiation, an ill-fated invasion force, led by Bertrand Clauzel, had to retreat from Constantine in 1836 in humiliation and defeat. However, the French captured Constantine under Sylvain Charles Valée the following year, on 13 October 1837.

Historians generally set the indigenous population of Algeria at 3 million in 1830.[24] Although the Algerian population decreased at some point under French rule, most certainly between 1866 and 1872,[25] the French military was not fully responsible for the extent of this decrease, as some of these deaths could be explained by the locust plagues of 1866 and 1868, as well as by a rigorous winter in 1867–68, which caused a famine followed by an epidemic of cholera.[26]

Resistance of Lalla Fadhma N'Soumer

The French began their occupation of Algiers in 1830, starting with a landing in Algiers. As occupation turned into colonization, Kabylia remained the only region independent of the French government. Pressure on the region increased, and the will of her people to resist and defend Kabylia increased as well.

In about 1849, a mysterious man arrived in Kabiliya. He presented himself as Mohamed ben Abdallah (the name of the Prophet), but is more commonly known as Sherif Boubaghla. He was probably a former lieutenant in the army of Emir Abdelkader, defeated for the last time by the French in 1847. Boubaghla refused to surrender at that battle, and retreated to Kabylia. From there he began a war against the French armies and their allies, often employing guerrilla tactics. Boubaghla was a relentless fighter, and very eloquent in Arabic. He was very religious, and some legends tell of his thaumaturgic skills.

Boubaghla went often to Soumer to talk with high-ranking members of the religious community, and Lalla Fadhma was soon attracted by his strong personality. At the same time, the relentless combatant was attracted by a woman so resolutely willing to contribute, by any means possible, to the war against the French. With her inspiring speeches, she convinced many men to fight as imseblen (volunteers ready to die as martyrs) and she herself, together with other women, participated in combat by providing cooking, medicines, and comfort to the fighting forces.

Traditional sources tell that a strong bond was formed between Lalla Fadhma and Boubaghla. She saw this as a wedding of peers, rather than the traditional submission as a slave to a husband. In fact, at that time Boubaghla left his first wife (Fatima Bent Sidi Aissa) and sent back to her owner a slave he had as a concubine (Halima Bent Messaoud). But on her side, Lalla Fadhma wasn't free: even if she was recognized as tamnafeqt ("woman who left her husband to get back to his family ," a Kabylia institution), the matrimonial tie with her husband was still in place, and only her husband's will could free her. However he did not agree to this, even when offered large bribes. The love between Fadhma and Bou remained platonic, but there were public expressions of this feeling between the two.

Fadhma was personally present at many fights in which Boubaghla was involved, particularly the battle of Tachekkirt won by Boubaghla forces (18–19 July 1854), where the French general Jacques Louis César Randon was caught but managed to escape later. On 26 December 1854, Boubaghla was killed; some sources claim it was due to treason of some of his allies. The resistance was left without a charismatic leader and a commander able to guide it efficiently. For this reason, during the first months of 1855, on a sanctuary built on top of the Azru Nethor peak, not far from the village where Fadhma was born, there was a great council among combatants and important figures of the tribes in Kabylie. They decided to grant Lalla Fadhma, assisted by her brothers, the command of combat.

Resistance of Emir Abd al Qadir

The French faced other opposition as well in the area. The superior of a religious brotherhood, Muhyi ad Din, who had spent time in Ottoman jails for opposing the bey's rule, launched attacks against the French and their makhzen allies at Oran in 1832. In the same year, jihad was declared[27] and to lead it tribal elders chose Muhyi ad Din's son, twenty-five-year-old Abd al Qadir. Abd al Qadir, who was recognized as Amir al-Muminin (commander of the faithful), quickly gained the support of tribes throughout Algeria. A devout and austere marabout, he was also a cunning political leader and a resourceful warrior. From his capital in Tlemcen, Abd al Qadir set about building a territorial Muslim state based on the communities of the interior but drawing its strength from the tribes and religious brotherhoods. By 1839, he controlled more than two-thirds of Algeria. His government maintained an army and a bureaucracy, collected taxes, supported education, undertook public works, and established agricultural and manufacturing cooperatives to stimulate economic activity.

The French in Algiers viewed with concern the success of a Muslim government and the rapid growth of a viable territorial state that barred the extension of European settlement. Abd al Qadir fought running battles across Algeria with French forces, which included units of the Foreign Legion, organized in 1831 for Algerian service. Although his forces were defeated by the French under General Thomas Bugeaud in 1836, Abd al Qadir negotiated a favorable peace treaty the next year. The treaty of Tafna gained conditional recognition for Abd al Qadir's regime by defining the territory under its control and salvaged his prestige among the tribes just as the shaykhs were about to desert him. To provoke new hostilities, the French deliberately broke the treaty in 1839 by occupying Constantine. Abd al Qadir took up the holy war again, destroyed the French settlements on the Mitidja Plain, and at one point advanced to the outskirts of Algiers itself. He struck where the French were weakest and retreated when they advanced against him in greater strength. The government moved from camp to camp with the amir and his army. Gradually, however, superior French resources and manpower and the defection of tribal chieftains took their toll. Reinforcements poured into Algeria after 1840 until Bugeaud had at his disposal 108,000 men, one-third of the French army.

One by one, the amir's strongholds fell to the French, and many of his ablest commanders were killed or captured so that by 1843 the Muslim state had collapsed.

Abd al Qadir took refuge in 1841 with his ally, the sultan of Morocco, Abd ar Rahman II, and launched raids into Algeria. This alliance led the French Navy to bombard and briefly occupy Essaouira (Mogador) under the Prince de Joinville on August 16, 1844. A French force was destroyed at the Battle of Sidi-Brahim in 1845. However, Abd al Qadir was obliged to surrender to the commander of Oran Province, General Louis de Lamoricière, at the end of 1847.

Abd al Qadir was promised safe conduct to Egypt or Palestine if his followers laid down their arms and kept the peace. He accepted these conditions, but the minister of war — who years earlier as general in Algeria had been badly defeated by Abd al Qadir — had him consigned in France in the Château d'Amboise.

French rule

Demography

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| e – Indicates that this is an estimated figure. Source: [28][29] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

French atrocities against the Algerian indigenous population

According to Ben Kiernan, colonization and genocidal massacres proceeded in tandem. Within the first three decades (1830–1860) of French conquest, between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Algerians, out of a total of 3 million, were killed due to war, massacres, disease and famine.[30][31] Atrocities committed by the French during the Algerian War during the 1950s against Algerians include deliberate bombing and killing of unarmed civilians, rape, torture, executions through "death flights" or burial alive, thefts and pillaging.[32][33][34] Up to 2 million Algerian civilians were also deported in internment camps.[35]

During the Pacification of Algeria (1835-1903) French forces engaged in a scorched earth policy against the Algerian population. Colonel Lucien de Montagnac stated that the purpose of the pacification was to "destroy everything that will not crawl beneath our feet like dogs"[36] The scorched earth policy, decided by Governor General Thomas Robert Bugeaud, had devastating effects on the socio-economic and food balances of the country: "we fire little gunshot, we burn all douars, all villages, all huts; the enemy flees across taking his flock."[36] According to Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison, the colonization of Algeria led to the extermination of a third of the population from multiple causes (massacres, deportations, famines or epidemics) that were all interrelated.[37] Returning from an investigation trip to Algeria, Tocqueville wrote that "we make war much more barbaric than the Arabs themselves it is for their part that civilization is situated."[38]

French forces deported and banished entire Algerian tribes. The Moorish families of Tlemcen were exiled to the Orient, and others were emigrated elsewhere. The tribes that were considered too troublesome were banned, and some took refuge in Tunisia, Morocco and Syria or were deported to New Caledonia or Guyana. Also, French forces also engaged in wholesale massacres of entire tribes. All 500 men, women and children of the El Oufia tribe were killed in one night,[39] while all 500 to 700 members of the Ouled Rhia tribe were killed by suffocation in a cave.[39] The Siege of Laghouat is referred by Algerians as the year of the "Khalya ," Arabic for emptiness, which is commonly known to the inhabitants of Laghouat as the year that the city was emptied of its population.[40][41] It is also commonly known as the year of Hessian sacks, referring to the way the captured surviving men and boys were put alive in the hessian sacks and thrown into dug-up trenches.[42][43]

From 8 May to June 26, 1945, the French carried out the Sétif and Guelma massacre, in which between 6,000 and 80,000 Algerian Muslims were killed. Its initial outbreak occurred during a parade of about 5,000 people of the Muslim Algerian population of Sétif to celebrate the surrender of Nazi Germany in World War II; it ended in clashes between the marchers and the local French gendarmerie, when the latter tried to seize banners attacking colonial rule.[44] After five days, the French colonial military and police suppressed the rebellion, and then carried out a series of reprisals against Muslim civilians.[45] The army carried out summary executions of Muslim rural communities. Less accessible villages were bombed by French aircraft, and cruiser Duguay-Trouin, standing off the coast in the Gulf of Bougie, shelled Kherrata.[46] Vigilantes lynched prisoners taken from local jails or randomly shot Muslims not wearing white arm bands (as instructed by the army) out of hand.[44] It is certain that the great majority of the Muslim victims had not been implicated in the original outbreak.[47] The dead bodies in Guelma were buried in mass graves, but they were later dug up and burned in Héliopolis.[48]

During the Algerian War (1954-1962), the French used deliberate illegal methods against the Algerians, including (as described by Henri Alleg, who himself had been tortured, and historians such as Raphaëlle Branche) beatings, torture by electroshock, waterboarding, burns, and rape.[34][49][50] Prisoners were also locked up without food in small cells, buried alive, and thrown from helicopters to their death or into the sea with concrete on their feet.[34][51][52][53] Claude Bourdet had denounced these acts on 6 December 1951, in the magazine L'Observateur, rhetorically asking, "Is there a Gestapo in Algeria? ."[54][55][56] D. Huf, in his seminal work on the subject, argued that the use of torture was one of the major factors in developing French opposition to the war.[57] Huf argued, "Such tactics sat uncomfortably with France's revolutionary history, and brought unbearable comparisons with Nazi Germany. The French national psyche would not tolerate any parallels between their experiences of occupation and their colonial mastery of Algeria." General Paul Aussaresses admitted in 2000 that systematic torture techniques were used during the war and justified it. He also recognized the assassination of lawyer Ali Boumendjel and the head of the FLN in Algiers, Larbi Ben M'Hidi, which had been disguised as suicides.[58] Bigeard, who called FLN activists "savages ," claimed torture was a "necessary evil ."[59][60] To the contrary, General Jacques Massu denounced it, following Aussaresses's revelations and, before his death, pronounced himself in favor of an official condemnation of the use of torture during the war.[61] In June 2000, Bigeard declared that he was based in Sidi Ferruch, a torture center where Algerians were murdered. Bigeard qualified Louisette Ighilahriz's revelations, published in the Le Monde newspaper on June 20, 2000, as "lies." An ALN activist, Louisette Ighilahriz had been tortured by General Massu.[62] However, since General Massu's revelations, Bigeard has admitted the use of torture, although he denies having personally used it, and has declared, "You are striking the heart of an 84-year-old man." Bigeard also recognized that Larbi Ben M'Hidi was assassinated and that his death was disguised as a suicide.

In 2018 France officially admitted that torture was systematic and routine.[63][64][65]

Hegemony of the colons

Political organization

A commission of inquiry established by the French Senate in 1892 and headed by former Prime Minister Jules Ferry, an advocate of colonial expansion, recommended that the government abandon a policy that assumed French law, without major modifications, could fit the needs of an area inhabited by close to two million Europeans and four million Muslims. Muslims had no representation in the French National Assembly before 1945 and were grossly under-represented on local councils. Because of the many restrictions imposed by the authorities, by 1915 only 50,000 Muslims were eligible to vote in elections in the civil communes. Attempts to implement even the most modest reforms were blocked or delayed by the local administration in Algeria, dominated by colons, and by the 27 colon representatives in the National Assembly (six deputies and three senators from each department).[citation needed]

Once elected to the National Assembly, colons became permanent fixtures. Because of their seniority, they exercised disproportionate influence, and their support was important to any government's survival.[66] The leader of the colon delegation, Auguste Warnier (1810–1875), succeeded during the 1870s in modifying or introducing legislation to facilitate the private transfer of land to settlers and continue the Algerian state's appropriation of land from the local population and distribution to settlers. Consistent proponents of reform, like Georges Clemenceau and socialist Jean Jaurès, were rare in the National Assembly.

Economic organization

The bulk of Algeria's wealth in manufacturing, mining, agriculture, and trade was controlled by the grands colons. The modern European-owned and -managed sector of the economy centered on small industry and a highly developed export trade, designed to provide food and raw materials to France in return for capital and consumer goods. Europeans held about 30% of the total arable land, including the bulk of the most fertile land and most of the areas under irrigation.[67] By 1900, Europeans produced more than two-thirds of the value of output in agriculture and practically all agricultural exports. The modern, or European, sector was run on a commercial basis and meshed with the French market system that it supplied with wine, citrus, olives, and vegetables. Nearly half of the value of European-owned real property was in vineyards by 1914. By contrast, subsistence cereal production—supplemented by olive, fig, and date growing and stock raising—formed the basis of the traditional sector, but the land available for cropping was submarginal even for cereals under prevailing traditional cultivation practices.

In 1953, sixty per cent of the Muslim rural population were officially classed as being destitute. The European community, numbering at the time about one million out of a total population of nine million, owned about 66% of farmable land and produced all of the 1.3 million tons of wine that provided the base of the Algerian economy. Exports of Algerian wine and wheat to France were balanced in trading terms by a flow of manufactured goods.[68]

The colonial regime imposed more and higher taxes on Muslims than on Europeans.[69] The Muslims, in addition to paying traditional taxes dating from before the French conquest, also paid new taxes, from which the colons were normally exempted. In 1909, for instance, Muslims, who made up almost 90% of the population but produced 20% of Algeria's income, paid 70% of direct taxes and 45% of the total taxes collected. And colons controlled how these revenues would be spent. As a result, colon towns had handsome municipal buildings, paved streets lined with trees, fountains and statues, while Algerian villages and rural areas benefited little if at all from tax revenues.

In financial terms Algeria was a drain on the French tax-payer. In the early 1950s the total Algerian budget of seventy-two billion francs included a direct subsidy of twenty-eight billion contributed from the metropolitan budget. Described at the time as being a French luxury, continued rule from Paris was justified on a variety of grounds including historic sentiment, strategic value and the political influence of the European settler population.[70]

Schools

The colonial regime proved severely detrimental to overall education for Algerian Muslims, who had previously relied on religious schools to learn reading and writing and engage in religious studies. Not only did the state appropriate the habus lands (the religious foundations that constituted the main source of income for religious institutions, including schools) in 1843, but colon officials refused to allocate enough money to maintain schools and mosques properly and to provide for enough teachers and religious leaders for the growing population. In 1892, more than five times as much was spent for the education of Europeans as for Muslims, who had five times as many children of school age. Because few Muslim teachers were trained, Muslim schools were largely staffed by French teachers. Even a state-operated madrasah (school) often had French faculty members. Attempts to institute bilingual, bicultural schools, intended to bring Muslim and European children together in the classroom, were a conspicuous failure, rejected by both communities and phased out after 1870. According to one estimate, fewer than 5% of Algerian children attended any kind of school in 1870. As late as 1954 only one Muslim boy in five and one girl in sixteen was receiving formal schooling.[71] The level of literacy amongst the total Muslim population was estimated at only 2% in urban areas and half of that figure in the rural hinterland.[72]

Efforts were begun by 1890 to educate a small number of Muslims along with European students in the French school system as part of France's "civilizing mission" in Algeria. The curriculum was entirely French and allowed no place for Arabic studies, which were deliberately downgraded even in Muslim schools. Within a generation, a class of well-educated, gallicized Muslims — the évolués (literally, the evolved ones)—had been created. Almost all of the handful of Muslims who accepted French citizenship were évolués; ironically, this privileged group of Muslims, strongly influenced by French culture and political attitudes, developed a new Algerian self-consciousness.

Relationships between the colons, Indigènes and France

Reporting to the French Senate in 1894, Governor-General Jules Cambon wrote that Algeria had "only a dust of people left her." He referred to the destruction of the traditional ruling class that had left Muslims without leaders and had deprived France of interlocuteurs valables (literally, valid go-betweens), through whom to reach the masses of the people. He lamented that no genuine communication was possible between the two communities.[73]

The colons who ran Algeria maintained a dialog only with the beni-oui-ouis. Later they thwarted contact between the évolués and Muslim traditionalists on the one hand and between évolués and official circles in France on the other. They feared and mistrusted the Francophone évolués, who were classified either as assimilationist, insisting on being accepted as Frenchmen but on their own terms, or as integrationists, eager to work as members of a distinct Muslim elite on equal terms with the French.

Separate personal status

Two communities existed: the French national and the people living with their own traditions. Following its conquest of Ottoman-controlled Algeria in 1830, for well over a century, France maintained what was effectively colonial rule in the territory, though the French Constitution of 1848 made Algeria part of France, and Algeria was usually understood as such by French people, even on the Left.[74]

Algeria became the prototype for a pattern of French colonial rule.

With nine million or so 'Muslim' Algerians "dominated" by one million settlers, Algeria had similarities with South Africa, that has later been described as "quasi-apartheid"[75] while the concept of apartheid was formalized in 1948.

This personal status lasted the entire time Algeria was French, from 1830 till 1962, with various changes in the meantime.

When French rule began, France had no well-established systems for intensive colonial governance, the main existing legal provision being the 1685 Code Noir which was related to slave-trading and owning and incompatible with the legal context of Algeria.

Indeed, France was committed in respecting the local law.

Status before 1865

On 5 July 1830, Hussein Dey, regent of Algiers, signed the act of capitulation to the Régence, which committed General de Bourmont and France "not to infringe on the freedom of people of all classes and their religion ."[76] Muslims still remain submitted to the Muslim Customary law and Jews to the Law of Moses; all of them remained linked to the Ottoman Empire.[77]

That same year and the same month, the July Revolution ended the Bourbon Restoration and began the July Monarchy in which Louis Philippe I was King of the French.

The royal "Ordonnance du 22 juillet 1834" organized general government and administration of the French territories in North Africa and is usually considered as an effective annexation of Algeria by France;[78] the annexation made all people legally linked to France and broke the legal link between people and the Ottoman Empire,[77] because International law made annexation systematically induce a régnicoles.[78] This made people living in Algeria "French subjects ,"[79] without providing them any way to become French nationals.[80] However, since it was not positive law, this text did not introduce legal certainty on this topic.[77][79] This was confirmed by the French Constitution of 1848

As French rule in Algeria expanded, particularly under Thomas-Robert Bugeaud (1841–48), discriminatory governance became increasingly formalised. In 1844, Bugeaud formalised a system of European settlements along the coast, under civil government, with Arab/Berber areas in the interior under military governance.[81] An important feature of French rule was cantonnement, whereby tribal land that was supposedly unused was seized by the state, which enabled French colonists to expand their landholdings, and pushed indigenous people onto more marginal land and made them more vulnerable to drought;[82] this was extended under the governance of Bugeaud's successor, Jacques Louis Randon.[81]

A case in 1861 questioned the legal status of people in Algeria. On 28 November 1861, the conseil de l'ordre des avocats du barreau d'Alger (Bar association of Algiers) declined to recognise Élie Énos (or Aïnos), a Jew from Algiers, since only French citizens could become lawyers.[77] On 24 February 1862 (appeal) and on 15 February 1864 (cassation), judges reconsidered this, deciding that people could display the qualities of being French (without having access to the full rights of a French citizen).[83]

Status since 1865

This section may be a rough translation from French. It may have been generated, in whole or in part, by a computer or by a translator without dual proficiency. (August 2022) |

Napoleon III was the first elected president of the French Second Republic before becoming Emperor of the French by the 1852 French Second Empire referendum after the French coup d'état of 1851. In the 1860s, influenced by Ismael Urbain, he introduced what were intended as liberalizing reforms in Algeria, promoting the French colonial model of assimilation, whereby colonised peoples would eventually become French. His reforms were resisted by colonists in Algeria, and his attempts to allow Muslims to be elected to a putative new assembly in Paris failed.

However, he oversaw an 1865 decree (sénatus-consulte du 14 juillet 1865 sur l'état des personnes et la naturalisation en Algérie) that "stipulated that all the colonised indigenous were under French jurisdiction, i.e., French nationals subjected to French laws ," and allowed Arab, Jewish, and Berber Algerians to request French citizenship—but only if they "renounced their Muslim religion and culture ."[84]

This was the first time indigènes (natives) were allowed to access French citizenship,[85] but such citizenship was incompatible with the statut personnel,[86] which allowed them to live within the Muslim traditions.

- Flandin argued that French citizenship was not compatible with Muslim status, since it had opposing laws on marriage, repudiation, divorce, and children's legal status.

- Claude Alphonse Delangle, senator, also argued that Muslim and Jewish religions allowed polygamy, repudiation, and divorce.[87]

Later, Azzedine Haddour argued that this decree established "the formal structures of a political apartheid ."[88] Since few people were willing to abandon their religious values (which was seen as apostasy), rather than promoting assimilation, the legislation had the opposite effect: by 1913, only 1,557 Muslims had been granted French citizenship.[81]

Special penalties were managed by the cadis or tribe head but because this system was unfair it was decided by a Circulaire on 12 February 1844 to take control of those specific fines. Those fines were defined by various prefectural decrees, and were later known as the Code de l'indigénat. Lack of codification means that there is no complete text summary of these fines available.[89]

On 28 July 1881, a new law (loi qui confère aux Administrateurs des communes mixtes en territoire civil la répression, par voie disciplinaire, des infractions spéciales à l'indigénat) known as the Code de l'indigénat was formally introduced for seven years to help administration.[90] It enabled district officials to issue summary fines to Muslims without due legal process, and to extract special taxes. This temporary law was renewed by other temporary laws: the laws of 27 June 1888 for two years, 25 June 1890, 25 June 1897, 21 December 1904, 24 December 1907, 5 July 1914, 4 August 1920, 11 July 1922 and 30 December 1922.[91] By 1897, fines could be changed into forced labor.[92]

Periodic attempts at partial reform failed:

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=French_AlgeriaText je dostupný za podmienok Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších podmienok. Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky použitia.

Antropológia

Aplikované vedy

Bibliometria

Dejiny vedy

Encyklopédie

Filozofia vedy

Forenzné vedy

Humanitné vedy

Knižničná veda

Kryogenika

Kryptológia

Kulturológia

Literárna veda

Medzidisciplinárne oblasti

Metódy kvantitatívnej analýzy

Metavedy

Metodika

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.

www.astronomia.sk | www.biologia.sk | www.botanika.sk | www.dejiny.sk | www.economy.sk | www.elektrotechnika.sk | www.estetika.sk | www.farmakologia.sk | www.filozofia.sk | Fyzika | www.futurologia.sk | www.genetika.sk | www.chemia.sk | www.lingvistika.sk | www.politologia.sk | www.psychologia.sk | www.sexuologia.sk | www.sociologia.sk | www.veda.sk I www.zoologia.sk