A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Free State of Prussia Freistaat Preußen (German) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State of the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany | |||||||||||||||

| 1918–1947 | |||||||||||||||

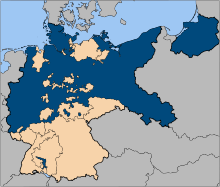

The Free State of Prussia within the Weimar Republic in 1925 | |||||||||||||||

| Anthem | |||||||||||||||

| Freistaat Preußen Marsch "Free State of Prussia March" (1922–1935) | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Berlin | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

• 1925[1] | 292,695.36 km2 (113,010.31 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1925[1] | 38,175,986 | ||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||

| • Type | Republic | ||||||||||||||

| • Motto | Gott mit uns "God with us" | ||||||||||||||

| Minister President | |||||||||||||||

• 1918 (first) | Friedrich Ebert | ||||||||||||||

• 1933–1945 (last) | Hermann Göring | ||||||||||||||

| Reichsstatthalter | |||||||||||||||

• 1933–1935 | Adolf Hitler | ||||||||||||||

• 1935–1945 | Hermann Göring | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | State Parliament | ||||||||||||||

• Upper Chamber | State Council | ||||||||||||||

• Lower Chamber | House of Representatives | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar • World War II | ||||||||||||||

| 9 November 1918 | |||||||||||||||

| 30 November 1920 | |||||||||||||||

| 20 July 1932 | |||||||||||||||

• Nazi seizure of power | 30 January 1933 | ||||||||||||||

| 25 February 1947 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

The Free State of Prussia (German: Freistaat Preußen, pronounced [ˌfʁaɪ̯ʃtaːt ˈpʁɔɪ̯sn̩] ) was one of the constituent states of Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it continued to be the dominant state in Germany during the Weimar Republic, as it had been during the empire, even though most of Germany's post-war territorial losses in Europe had come from its lands. It was home to the federal capital Berlin and had 62% of Germany's territory and 61% of its population. Prussia changed from the authoritarian state it had been in the past and became a parliamentary democracy under its 1920 constitution. During the Weimar period it was governed almost entirely by pro-democratic parties and proved more politically stable than the Republic itself. With only brief interruptions, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) provided the Minister President. Its Ministers of the Interior, also from the SPD, pushed republican reform of the administration and police, with the result that Prussia was considered a bulwark of democracy within the Weimar Republic.[2]

As a result of the Prussian coup d'état instigated by Reich Chancellor Franz von Papen in 1932, the Free State was subordinated to the Reich government and deprived of its independence. Prussia had thus de facto ceased to exist before the Nazi Party seized power in 1933, even though a Prussian government under Hermann Göring continued to function formally until 1945. After the end of the Second World War, by decree of the Allied Control Council, the de jure abolition of Prussia occurred on 25 February 1947.

Establishment (1918–1920)

| History of Brandenburg and Prussia |

|---|

|

|

| Present |

|

Revolution of 1918–1919

On 9 November 1918, in the early days of the Revolution of 1918–1919 that brought down the German monarchy, Prince Maximilian von Baden, the last Chancellor of the German Empire – who like most of his predecessors was also Minister President of Prussia – announced the abdication of Wilhelm II as German Emperor and King of Prussia before he had in fact done so.[3]

On the same day, Prince Maximilian transferred the office of Reich Chancellor to Friedrich Ebert, the chairman of the Majority SPD (MSPD), which was the largest party in the Reichstag. Ebert then charged Paul Hirsch, the MSPD's party leader in the Prussian House of Representatives, with maintaining peace and order in Prussia. The last Minister of the Interior of the Kingdom of Prussia, Bill Drews, legitimized the transfer of de facto governmental power to Hirsch. On 10 November Ebert found himself forced to form a joint government, the Council of the People's Deputies, with representatives of the Independent SPD (USPD), a more leftist and anti-war group that had broken away from the original united SPD in 1917, and to enter into an alliance with the council movement, a form of council communism.

On 12 November 1918 commissioners from the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils of Greater Berlin, including Paul Hirsch, Otto Braun (MSPD) and Adolph Hoffmann (USPD), appeared before the last Deputy Minister President of Prussia, Robert Friedberg. They declared the previous government deposed and claimed the management of state affairs for themselves.[4] On the same day the commissioners issued instructions that all departments of the state should continue their work as usual. A manifesto, "To the Prussian People!", stated that the goal was to transform "the old, fundamentally reactionary Prussia ... into a fully democratic component of the unified People's Republic."[5]

Revolutionary cabinet

On 13 November the new government confiscated the royal property and placed it under the Ministry of Finance. The following day, the Majority and Independent Social Democrats formed the Prussian revolutionary cabinet along the lines of the coalition at the Reich level. It included Paul Hirsch, Eugen Ernst and Otto Braun of the MSPD and Heinrich Ströbel, Adolph Hoffmann and Kurt Rosenfeld of the USPD. Almost all departments were under ministers from both parties. Hirsch and Ströbel became joint chairmen of the cabinet. Other non-partisan ministers or ministers belonging to different political camps were also included, such as the Minister of War, initially Heinrich Schëuch, then from January 1919 Walther Reinhardt. The narrower, decisive political cabinet, however, included only politicians from the two workers' parties.[6] Since the leadership qualities of the two chairmen were comparatively weak, it was mainly Otto Braun and Adolph Hoffmann who set the tone in the provisional government.[7]

Political change and its limits

On 14 November the Prussian House of Lords (Herrenhaus) was abolished and the House of Representatives dissolved. The replacement of political elites, however, remained limited during the early years. In many cases the former royal district administrators (Landräte) continued to hold office as if there had been no revolution. Complaints against them by the workers' councils were either dismissed or ignored by Interior Minister Wolfgang Heine (MSPD). When conservative district administrators themselves requested to be dismissed, they were asked to stay on in order to maintain peace and order.

On 23 December the government issued an administrative order for the election of a constitutional assembly. Universal, free and secret suffrage for both women and men replaced the old Prussian three-class franchise. At the municipal level, however, it took eight months before the existing governmental bodies were replaced by democratically legitimized ones.[8] Deliberations concerning a fundamental reform of property relations in the countryside, in particular the breaking up of large landholdings, did not bear fruit. The manor districts that were the political power base of the large landowners remained in place.[9]

In educational policy, Minister of Culture Adolph Hoffmann abolished religious instruction as a first step in a push towards the separation of church and state. The move triggered considerable unrest in Catholic areas of Prussia and revived memories of Bismarck's 1870s Kulturkampf ('cultural conflict') against the Catholic Church. At the end of December 1919, MSPD Minister Konrad Haenisch rescinded Hoffmann's decree. In a letter to the Cardinal of Cologne Felix von Hartmann, Minister President Hirsch assured him that Hoffmann's provisions for ending clerical supervision of schools had been illegal because they had not been voted on in the cabinet. More strongly than any other government measures, Hoffmann's socialist cultural policies turned large segments of the population against the revolution.[10]

The Christmas Eve fighting in Berlin between the People's Navy Division and units of the German army led to the withdrawal of the USPD from the government in both Prussia and at the Reich level. The dismissal of Emil Eichhorn (USPD) as Berlin's police chief triggered the failed Spartacist Uprising of 5–12 January 1919 that attempted to turn the direction of the revolution towards the founding a communist state.

Separatist tendencies and the threat of dissolution

Prussia's continued existence was by no means assured in the aftermath of the revolution. In the Rhine Province, the advisory council of the Catholic Centre Party, fearing a dictatorship of the proletariat, called on 4 December 1918 for the formation of a Rhineland-Westphalian republic independent of Prussia. In the Province of Hanover, 100,000 people signed an appeal for territorial autonomy. In Silesia too there were efforts to form an independent state. In the eastern provinces, a revolt broke out at Christmas 1918 with the aim of restoring a Polish state. The movement soon encompassed the entire Province of Posen and eventually took on the character of a guerrilla war.[11][12]

Even for many supporters of the Republic, Prussian dominance seemed a dangerous burden for the Reich. Hugo Preuß, author of the draft version of the Weimar Constitution, originally envisaged breaking Prussia into various smaller states. Given Prussian dominance in the former empire, there was sympathy for the idea. Otto Landsberg (MSPD) of the Council of the People's Deputies commented, "Prussia occupied its position with the sword and that sword is broken. If Germany is to live, Prussia in its present form must die."[13]

The new socialist government of Prussia was opposed to such a move. On 23 January 1919 participants in an emergency meeting of the central council and the provisional government spoke out against Prussia's dissolution. With the Centre Party abstaining, the State Assembly during its first sessions adopted a resolution against a possible breakup of Prussia. Aside from a few exceptions, which included Friedrich Ebert, there was little support for it even among the Council of the People's Deputies at the Reich level because it was seen as the first step toward the secession of the Rhineland from the Reich.[14][15]

The mood in Prussia was more uncertain. In December 1919 the State Assembly passed a resolution by 210 votes to 32 that stated: "As the largest of the German states, Prussia views its first duty to be an attempt to see whether the creation of a unified German state cannot be achieved."[16]

State Assembly and coalition government

On 26 January 1919, one week after the 1919 German federal election, elections were held for the constituent Prussian State Assembly. During the campaign, reaching out to female voters, who were going to the polls for the first time, played an important role. In Catholic regions of the state, Hoffmann's anti-clerical school program helped the Centre Party to mobilize its voter base.[17] The MSPD emerged as the strongest party, followed by the Centre and the German Democratic Party (DDP). The Assembly met for the first time on 13 March 1919, during the final days of the violent Berlin March battles and the Ruhr uprising.